Liska Jacobs’s provocative debut novel, Catalina, sets a young woman on the edge and follows her downward spiral following the end of an affair with her married boss at MoMA. Elsa is lost, lonely, and full of rage, and after agreeing to a journey to Catalina Island with her college friends, she tries to numb her painful memories and dark desires with drugs and alcohol, hell-bent on destruction. Here, Jacobs joins Linde B. Lehtinen, an assistant curator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, to discuss how beauty, art, and gender intertwine in Catalina.

Liska: I know the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art recently opened its new space—which is nearly three times larger than your old building. I imagine this presents a lot of opportunities and challenges as a curator.

Linde: There are many fascinating and challenging aspects of curating, especially with such a large part of the museum devoted specifically to the medium of photography (the Pritzker Center for Photography encompasses 15,000 square feet). I work a lot on temporary exhibitions, which involves everything from collaborating with living artists, developing innovative themes and connections between artworks, and coordinating logistics for getting the work on the wall! With such a large space, our team has an exciting opportunity to simultaneously mount both large-scale surveys about individual artists as well as more focused, thematic shows.

We try to find a balance between showcasing contemporary, emerging artists and interpreting and displaying more established photographers. It’s also important that we keep up with the ongoing dialogues taking place about photography, since it is such a powerful medium in both the social and artistic spheres.

Liska: Compared to somewhere like the Getty, which presents contemporary shows but focuses more on historical context, SFMOMA is about the right now. What exhibition are you working on currently?

Linde: I’m working with our senior curator of photography Clément Chéroux on an exhibition called The Train: RFK’s Last Journey which opens in March 2018. It looks at three different perspectives on the funeral train of Robert F. Kennedy on June 8, 1968 as it moved from New York City to Washington, D.C. The project started with photojournalist Paul Fusco’s stirring color photographs of the event, which were taken from the train itself, capturing thousands of mourners who spontaneously gathered beside the railroad tracks to pay their respects. The second part of the show looks at a project by Rein Jelle Terpstra, a contemporary Dutch artist who was influenced by Fusco’s photographs. In 2014 he started finding the original snapshots that people took that day from their point of view alongside the tracks. He calls it The People’s View.

The third part of the show will feature a work by Philippe Parreno, a contemporary French artist who made an incredible 70mm film in 2009 referencing Fusco’s photographs and recreating RFK’s final journey by renting a train and hiring one hundred actors dressed in 1960s outfits. The resulting film presents a strange, floating perspective, which Parreno refers to as “the point of view of the dead.”

Adrian Piper – Catalysis IV, 1971

Liska: I love that—the present reaching back to the past. You and I met while both working at the Getty Research Institute, where I was a Special Collections Assistant, and you were a Research Assistant. In my novel, Catalina—which I believe you read—there is a lot of material I took from our time at the Getty and the art world in general. Elsa is an executive assistant to a world-renowned curator (who she’s also been having an affair with). She’s very much in love with museums—not art so much as the institution itself. I’m curious what you thought of the book, and its themes of beauty and art.

Linde: Firstly, I read the book on my daily train commute to my museum job, which somehow made it much more pleasurable and meaningful to read. I didn’t want to put the book down. Reading it triggered many memories from our Getty days, and I loved how you referenced a lot of the behind-the-scenes moments of working at such a large, prestigious institution. Some of the themes I picked up on that I related to most were the difficulties of navigating the art world, the objectification of women, and the struggles of balancing a museum career with the desire or ideal of having a family. Now I’ll turn this back to you: How did your time at the Getty shape your initial idea for this novel?

Liska: One of the things I noticed while at the Getty was that an overwhelming number of researchers and curators were women, and they all seemed to be under tremendous pressure to have it all. Not just succeed in their field but routinely publish, marry, have a family. And a museum is supposed to be this pillar of liberal, forward thinking, right? If there’s anywhere a woman can “have it all,” it should be there. Sure, women are often the object, the muse, the painting in the museum—but by curating the show, succeeding in their field, they can take the narrative back. Yet many of the acquisitions were by male artists, many shows were male artist-dominated. It was striking to me to work in a place so exalted for its forward thinking, yet to still feel like somehow it was a bit backwards. So, all of that kind of pissed me off! Maybe you picked up on some of Elsa’s rage?

I think especially in this current political climate that the female voice and presence has to be more charged than ever before.

Linde: I agree that there are so many contradictions within the art/museum/curatorial world that are maddening at times. I think especially in this current political climate that the female voice and presence has to be more charged than ever before. It feels like the stakes are so much higher. I connected with Elsa’s rage on several levels. It’s hard to know when to bring my feelings to the surface though. This passage from Catalina took my breath away because I realized I was a bit of both characters Charly and Elsa in this: “She should know it’s a dangerous thing to be a woman. We want things, just like anyone else. Power, control, success—more than the world has to offer us. So we shove it down, hush it up, hope that it doesn’t tear us apart. I should tell her this but I’m worried she might not feel the same—that she is cracking up from not being able to toe the line, whereas I want to destroy it entirely.”

Liska: Yeah that one broke me, because I knew it meant Elsa would not have a happy ending. We don’t reward women for being angry.

Linde: After reading that, I felt empowered, sad, and a little destroyed all at once.

Judy Dater – Self Portrait with mist

Liska: It’s because it’s unfair! Even in art—the place that is supposed to be boundless—somehow still has rules, especially for women, and that is deeply depressing. Which brings me to female artists. Recently you said you visited Judy Dater and it got you thinking about women in the art world. Do you feel comfortable elaborating?

Linde: When I visited Judy at her studio, I pondered the major role she had as a female artist in the photography world in the 1970s. Her work was everywhere then, and it is in many museum collections today, including SFMOMA’s. She was a female photographer surrounded by many male teachers and colleagues, trying to distinguish herself and explore new territory—especially using her own body in her photographs.

Liska: Are there other female artists you can think of who use their body in their art? In Catalina Elsa is very aware of her effect on men. Her freedom with her body is something I don’t have, but I thought it was important for her to use her body as a kind of currency. I think a lot of female artists turn objectification on its head as a way to steal the power back.

Linde: There are several artists that I can think of who use their bodies to subvert the male gaze and take the power back, as you describe it, and as Elsa does at times. I am thinking of Adrian Piper, who did a lot of performances in public spaces using her body in confrontational ways to draw attention to female objectification as well as racism. She stuffed a large white towel in her mouth and rode the subway like that. Or Hannah Wilke covered her body in small vulvas made of chewing gum in order to counter female stereotypes and create what she herself called a kind of “Venus envy.”

Liska: Oh, I love that. Do you think those women were successful in subverting the male gaze?

Elsa most definitely is not, although she struggles against it.

Linde: I think it’s more about how each of their works provoke and incite a dialogue about what it means and feels like to be seen and consumed by males. I think Elsa is deeply aware of what her beauty can both generate and take down, and that gives her a certain power. I see her vulnerabilities, but I feel like she knows how to use people in a way that is both troubling and strangely alluring.

Liska: Totally! Elsa is very aware. “There’s always so much in that look,” she tells us when men ogle at her.

Linde: Did you have certain artists in mind as you were constructing her character? I love how you make specific connections between what a work of art looks like and then weave it into the way she perceives a situation.

Liska: That’s a really good question. Funny enough I wanted to take on artists who were considered “masculine”—sort of the Hemingways of the visual art world. I read an article in The New Yorker about Picasso and his “animal magnetism,” how he was this incredible lover and thinker and artist. I knew that was the exhibition I wanted Elsa and her boss Eric to be working on. Mike Kelley came about for similar reasons. I hadn’t yet worked at the Mike Kelley Foundation, so my knowledge of his artwork was limited to museum shows, but a lot of it is very male centric—penises galore.

Linde: I was really intrigued by the Eric character as the classic male curator type. Can you tell me what inspired that?

Liska: Well I started working at the Getty when I was 25, which is an impressionable age. I was very doe-eyed and eager. There were many men in prestigious positions who dressed and spoke differently than any men I’d known before. Men in expensive three-piece suits, who had access and knowledge of the five vaults filled with, to use a simple term, ‘treasure.’ Italian Futurism, Impressionist painters’ letters, rare books—for God’s sake one of them introduced me to the Guerrilla Girls. Basically, I can see how a young woman could be swept up by it all—and how a curator of a certain age would tumble headlong into it too. Funny enough, there is a curator at MoMA who curated a Mike Kelley show. I didn’t know this while writing the book, but it was brought to my attention later. This curator is pretty damn attractive too, so hopefully he also has a good sense of humor!

Do you think the role of the female curator is different from that of the male curator? Do you feel a responsibility now that you have a hand in controlling narrative, so to speak, to represent female artists or other overlooked, marginalized artists?

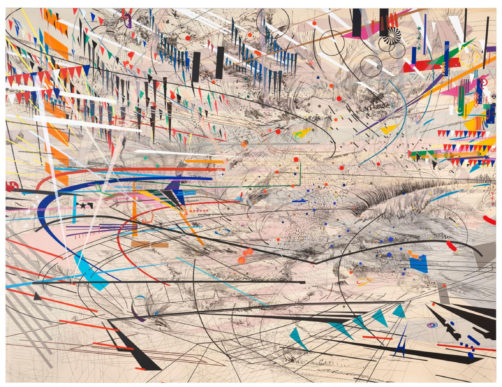

Julie Mehretu, Stadia I, 2004

Linde: There is definitely more attention being paid in recent years to both the female artist and female curator, and I think there is a big difference in how we can interpret and represent a wider range of perspectives and conflicts surrounding gender. As a female, half-Filipino curator I can’t help but take into account my own identity when it comes to the artists, themes, and issues that I want to investigate within the museum and art world context. There have been several all-women group shows that are seeking to find the overlooked artists who were not always part of the classic art historical narrative, such as the recent Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985 at the Hammer Museum or Women of Abstract Expressionism at the Denver Art Museum. At SFMOMA, we have a commissioned work up right now by Julie Mehretu, an artist who is Ethiopian-American, gay, a mother—basically a range of identities. At the same time, you have to consider that not every artist wants to have their work interpreted through how they self-identify in terms of race or gender. So I’m constantly negotiating how to bring new artists and perspectives into the museum space.

Liska: It is all about negotiating isn’t it? I think that’s something women do all the time.

Linde: So as you were shaping Elsa’s character, were you looking to anyone in particular as inspiration? How much of you is in Elsa?

Liska: Great question, one that always gives me a pause. There’s definitely some of my own anger in Elsa—about loneliness, friendship, being disillusioned by your dream. Working at the Getty really did a number on me. I was so convinced it was where I belonged, that the people there were my people, and it hurt to realize that the Getty is just like any other place, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, it just means it can’t be a dream because it’s real. Filled with real people, complex relationships, disappointments—hiring freezes, layoffs, etc.

But Elsa isn’t me, thank God. I lack her confidence, her beguiling effect on men. That part of her was inspired by female characters of classic novels, like Lady Brett Ashley in The Sun Also Rises, or Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby. I thought how exhausting it must have been for them to continually be idolized and chased after by the male protagonists. They must have been filled with their own kind of rage, and I wanted to explore that.

Linde: I appreciated that her character could be both angry at the world (and at men in particular) but could also revert back to sweeter memories of her childhood like going to the Met for the first time and noticing the people who worked for museums even then. I loved that she has this passion for the institution, not necessarily just the artwork. Even if she eventually becomes disillusioned by it.

Liska: There’s something safe about a museum, isn’t there? Just the smell of that rarefied museum air. Taking the 405, wrestling traffic, hiking up that hill to get to the Getty, but then you use your badge at the door, it unlocks, and everything changes.

Linde: Absolutely. It feels like we are part of a secret community at times, that we can come out of the hidden doors every so often, but that so much takes place behind the scenes in order for us to finally reveal something to the public. Then it all starts to feel a little more vulnerable and raw.

I tend to sink deeper into the art world as a sort of balm when the world feels too threatening or hectic.

Liska: I tend to sink deeper into the art world as a sort of balm when the world feels too threatening or hectic. Art can offer a kind of solace. It can make the viewer feel not alone.

Linde: Art definitely has a way of bringing together communities and resolving conflicts. I’m glad that as a writer and a curator we have each found a way to express ourselves and find inspiration in the art world. From our formative years at the Getty to where we are now, I think we’ve both grown so much and finally found our voices.

Liska: Aww. I’m blushing.

Liska Jacobs holds an MFA from the University of California, Riverside. Her essays and short fiction have appeared in The Rumpus, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Literary Hub, The Millions, and The Hairpin, among other publications. Catalina is her first novel. (Author photo credit – Jordan Bryant)

Linde B. Lehtinen is assistant curator of photography at SFMOMA. She received her BA in art history from the University of Chicago and MA and PhD in art history from the University of Wisconsin–Madison where she wrote her dissertation on the work of American modernist photographer Paul Outerbridge. Prior to moving to the Bay Area, Lehtinen worked for several museums in both education and curatorial departments, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Research Institute, and Skirball Cultural Center. Her research and curatorial work has ranged from interwar mass advertising culture to conceptual photography. She has also published several articles and presented lectures on the history of photography in America. (Author photo credit – Raphye Alexius)