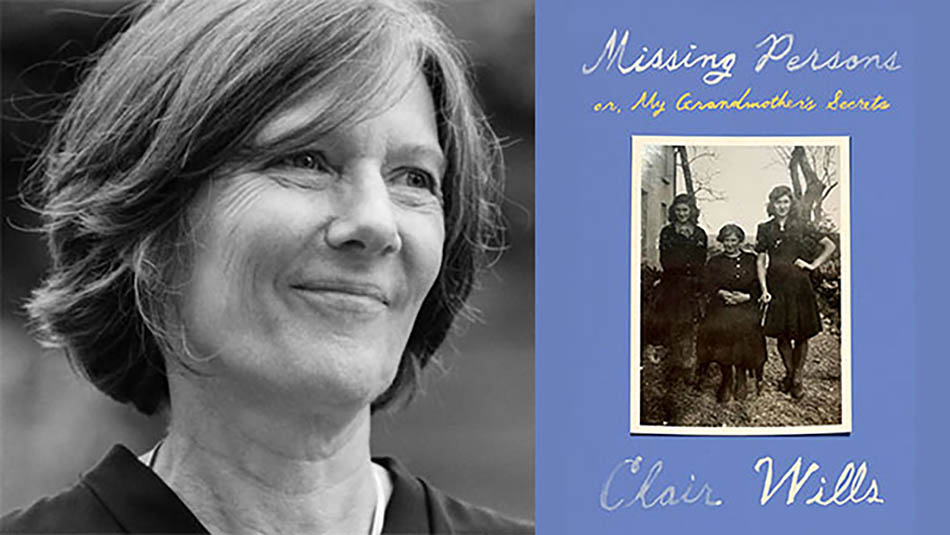

A conversation between Clair Wills and her editor Jonathan Galassi about Missing Persons, and how Clair blends memoir with social history to movingly explore the holes in the fabric of modern Ireland, and in her own family story.

Jonathan Galassi: Clair, let’s begin by talking about how you’ve thought about your overall interests as a writer, your engagement with Irish and English history, and how this new book extends and alters that trajectory. First off, how did you become a writer?

Clair Wills: My first thought is that for me, writing is reading—interpreting, or figuring something out. I can’t separate the two. I grew up with a strong sense of my Irishness, even though (or perhaps because!) my father was English, and we lived in an area of South London which didn’t have a strong Irish community. Year after year we slogged back and forth between our house in Croydon and my grandmother’s small farm in the West of Ireland, where my mother grew up, and by definition I didn’t completely belong in either place. I don’t mean that I felt ill at ease, but I was undeniably in-between. Elizabeth Bowen said somewhere that she felt most at home on the Irish sea, and that captures something of what I mean. I think one of the things I was practising, without knowing it, was how to explain one half of me to the other half. It’s the condition of childhood to be constantly trying to figure things out, but the children of first-generation immigrants are always glossing their own experience, explaining the relationship between one way of understanding things and another, if only to themselves. Sometimes that impulse to footnote became a requirement and a burden—in 1974, when I was eleven, the IRA bombed two pubs in Guildford (not far from where we lived) that were popular with British servicemen, killing five people and seriously wounding scores of others. A month later 21 were killed and nearly two hundred were injured by the pub bombings in Birmingham. I was one of only two Catholics in my year at secondary school, and you couldn’t help but become very aware of loyalties, and how they are perceived—very aware of layers of speech and silence. Mostly the slight tangent was unspoken, but there was definitely translating going on.

Later, when I got to university I gravitated to poetry, Coleridge and Shelley in particular, and I spent a whole term in my final year reading nothing but Yeats—I went to sleep with him, woke up with him, ate my lunch with him propped against the pepper grinder. His rhythms have gone deep inside, though I hope not his politics. I was fascinated by the way in which these writers’ complicated, doubtful, yet entrenched attitudes to revolutionary violence and bloodshed were written and overwritten in the poems, said and unsaid. My first book was about the poetry of the Northern Ireland troubles; then I wrote a history of Ireland during the Second World War, and a short book on the 1916 Rising. At the time I thought they were all very different books but looking back I can see that in each case that they are about crises in the relationship between Britain and Ireland. I was interested in how people negotiate their public and private allegiances, and in the way in which people betray those allegiances in writing. I think of writing as a kind of bloodsport I guess—the results aren’t always pretty.

JG: In Missing Persons you decided to address this subject (and others) more personally. What motivated this turn?

CW: I’m torn between two ways of answering, so I’ll give both.

The first answer has to do with a kind of compulsion, or a need to figure something out in my own family. I could read certain things off the surface of the way my family worked when I was a child.I knew there were people missing, people we never saw—but the why was never explained. In fact, certain kinds of misdirection were built into the family mythology. The fact that my mother had made a successful career in nursing, and that her four daughters passed entrance exams and went to good schools and universities, while several of her brothers lived (in the same city) in labourers’ lodgings, without families or steady jobs or the forward momentum we associate with a life story, was put down to a combination of luck (meeting my father) and hard work. But that was certainly not the whole truth. What I didn’t know as a child was that my uncles’ failure to integrate into daily life in England, their curtailed lives, was partly a result of Irish moral codes around sex and sexuality, and a series of catastrophic decisions that were made in 1955, when my uncle Jackie fathered a child with his nineteen-year-old neighbour Lily. What I could read was my mother’s sadness in relation to her brothers, and this book is one result of a long-felt compulsion to try to understand the reasons for that sadness. My mother often spoke of her brothers, Jackie and Thomas, though we rarely saw them. She quite straightforwardly missed them, I guess. I once asked, when I was ten or eleven: “What does uncle Thomas do?” I vividly remember the slight hesitation, the catch in her throat before she replied, “He’s a mason”. It wasn’t a word I knew, and I asked her to explain it. For a long time afterwards I had a mental image of my uncle as a sort of medieval craftsman, carving houses. She didn’t want to say: he’s a labourer, he digs ditches and lays cables, and pours concrete. Not, I think, because she was a snob, but because she was worried I might be.

The second answer is methodological. What I wanted to understand through writing this book was what happened to the women who fell on the wrong side of sexual morality and social respectability—the women who ended up in mother and baby homes, and their children—but also why it happened. Why did my uncle abandon Lily? Why did my grandmother refuse to acknowledge her grandchild—my first cousin, who was just seven years older than me? There are archival records for the institutions that governed and controlled Irish sexual and reproductive lives—the mother and baby homes, the Magdalen laundries, the orphanages and industrial schools. But there are no written sources explaining the behaviour of the families of the women and children who ended up in these institutions, or there are very few. If I wanted to understand why families consented to the Institutions it made sense to start with my own family, and the sources that were available to me: the secrets that were kept in the family and those that weren’t, the ellipses and misdirections built into the stories through which the family understood itself, and the generational battles over codes of behaviour, including who has the right to tell secrets and when. In the end I came to understand that I am one of the records in this story—how sex and illegitimacy and the ideal or normative family has been policed in Britain and Ireland, through the twentieth century, is archived in me and my own attitudes—right down to my decision when I got pregnant as a student in the late eighties to go ahead and have the baby on my own.

JG: How does your family’s story reflect the Church’s hold on Irish mores–which hadn’t always been so strong before the war, before Independence, if I’m not wrong.

CW: When I started writing the book I imagined it as an exploration of the legacy of Ireland’s church-state institutional regime, its impact on people in my grandmother’s and my mother’s generation, and in turn how that history impacted me, or on us. I and my sisters and cousins had, between us, no fewer than five children outside marriage—in the 1980s and ’90s, when having a baby on your own wasn’t yet the norm—and I wanted to think about what was going on there. Though I do think of my family story as typical, rather than exceptional. 57,000 children were born in Irish mother and baby homes between 1922 and 1998— and that’s the lowest estimate. They all had grandparents, and fathers, and aunts and uncles. All the women who entered the homes had siblings and neighbours and school friends and colleagues. We are talking about a whole society that learnt to look away from its missing persons.

So the book is an investigation of some family secrets, but it’s also an account of a whole culture of secrecy around sex and sexuality.

In the period before independence when my grandmother was growing up, no-one was going to shop anyone to the authorities, because the authorities were British. Keeping secrets in this period, particularly women keeping secrets between themselves, was a form of care. After the famine the Catholic Church had a shaky hold on the rural Irish poor. But the Church steadily tightened its hold on its parishioners through the late decades of the nineteenth century. And one of the consequences was a transformation of Irish family life. It was as though the tricky business of intimate relationships was handed over to a church-state bureaucracy to manage. It must have seemed the sensible thing to do, if you wanted to preserve your respectability, to hand your pregnant daughter over to the local priest to manage the problem. This was their own people saying, we’ll keep your secret for you.

JG: One of the deeply moving aspects of your story was the tragic effect of these secret arrangements on the fathers of these children, personified here by your Uncle Jackie. They too became missing persons—they were basically excised from their communities, they became exiles who played a defined role in the British-Irish colonial structure, but their lives in Ireland were effectively over, sacrificed to a social system. How was this understood?

CW: Not all the fathers of illegitimate babies were excised, or exiled. Many of them continued to live in their communities and turned their backs on the women they’d fathered children with. In a country where both contraception and abortion were illegal (artificial birth control wasn’t legalised in Ireland until 1979, and then for “bona fide” married couples only), arguably the only “responsible” answer to an unplanned pregnancy was a forced marriage, and that’s no answer at all. For men like my uncle, sex and desire was a catastrophe (as they were for his lover too). He lost his farm, his livelihood, his relationship with his family, his lover, his daughter, and as far as I can work out he seems to have accepted that there was nothing to be done about any of it.

I think part of the reason for that was because disappearing to England was so easy. There were no questions asked. He joined thousands of other Irish men, escaping the stagnant economy back home to build the roads and dig the ditches for Britain’s post-war boom. You see these lonely, bewildered, or defensive men everywhere in Irish literature—in Beckett, John McGahern, Tom Murphy, John B. Keane. They very rarely get a backstory that has to do with sex, or the politics of sexual respectability—that story is reserved for women, who bear all the signs of it in their bodies. But the fathers are part of the story—thousands of men whose futures were curtailed, and who never knew their children. I think the brutality of that experience hasn’t yet been acknowledged—and it needs to be.

JG: And how did this all change? What happened that led to the freedom and self-determination you have had/won?

CW: I think the sexual freedom and self-determination that my generation has enjoyed—to the extent that we have enjoyed it, which is not universal—was partly won for us by our parents. My mother, my aunt, and my uncles saw the violence that was done in the name of social and sexual respectability and they were determined not to perpetuate it. It is not simply that they welcomed our unconventional family arrangements, though they did. They also refused to keep the family’s secrets. My aunt told me about my missing cousin. My mother told me (eventually) about my grandmother’s premarital pregnancy. They knew that keeping secrets after they have outlived their usefulness is dangerous. But I don’t underestimate how difficult it must have been to break the family silence. It’s costly, betraying the habits of reserve and indirection that enable people to survive, especially in small communities.

I try to acknowledge that cost in the book. Secrets and silences are my subject, but they are also my method. I wrote the book by trying to work out what was meant when things weren’t said, or when a story didn’t quite add up. I say in the book that we all know what it feels like to inherit a story, and a set of beliefs, we only partially understand. But I am convinced that the manner in which we inherit the past—how we know about it and how we think about it, not simply what we know about it—can tell us things about how we live in the present.

In practice what it meant for me was that I had to examine my own shame, think about the silences I haven’t wanted broken. I didn’t really feel I could write about family loss, the loss of children, until I had examined what it felt like for me. I wanted to try to get as close as I could to how the experiences I talk about in the book might have felt, including thinking about my own quasi-illegitimacy as an Irish person—obviously I’m using the word as a metaphor at this point.

I think what I mean is that if we haven’t got written records explaining how and why our families made use of the institutions and what they thought about them, we do have ourselves. I am one of the records in this story. People in my generation are the archives of this history and one thing we might be able to do to get closer to an understanding of the past is to read the traces it has left in us.

JG: Part of the power of your book lies in its universality. As you suggest, these home truths have been an unspoken intergenerational inheritance forever and we’ve all experienced them in one way or another.Your parents’ generation broke the cycle, which must have something to do with the weakening repressive power of political and religious and cultural institutions. How do you think your children’s generation will think about your story?

CW: The relationship between past and present, and between generations, gets very tangled when we are talking about a culture and a community that stretches from rural Ireland to Dublin or London or Birmingham. And I don’t mean that things are more “behind” in the country. I’ve had a tremendous response to the book from young people—who want to know more about what really went on and who are trying, I think, to bring their almost visceral understanding that the past isn’t over yet (sexuality still gets policed; families are still at the mercy of institutions) into conversation with a public, political discourse that champions the brave new world of inclusivity, diversity, and so on. It’s like there’s a glitch in the motor which is supposed to produce change. The language is all about compassionate acceptance—or at least it tends to be in Ireland, where reproductive rights have become enshrined in law, and where it isn’t currently cool to flaunt your misogyny—but where it’s still hard to talk about your abortion, or your search for your birth mother, where a sense of shame around the family, sex and sexuality still nudges at the corner of your vision.

The situation is obviously different in the United States, where the past isn’t simply not over yet, it’s beginning again—this week in Arizona we skipped back to 1864, for example. I think this is why we need to keep talking about how families get policed, including both who gets to have a child and who gets to not have one. The delayed past will be knitted into the future for our kids unless they find a way of unlearning it—which, to their credit, they are very up for doing.

Clair Wills is the King Edward VII Professor of English Literature at the University of Cambridge. Her books include Lovers and Strangers: An Immigrant History of Post-War Britain, named the Irish Times International Nonfiction Book of the Year, and That Neutral Island: A Cultural History of Ireland During the Second World War, winner of the PEN Hessell-Tiltman Prize, among other works. She is a frequent contributor to the London Review of Books, The New York Review of Books, and other publications. She lives in London.