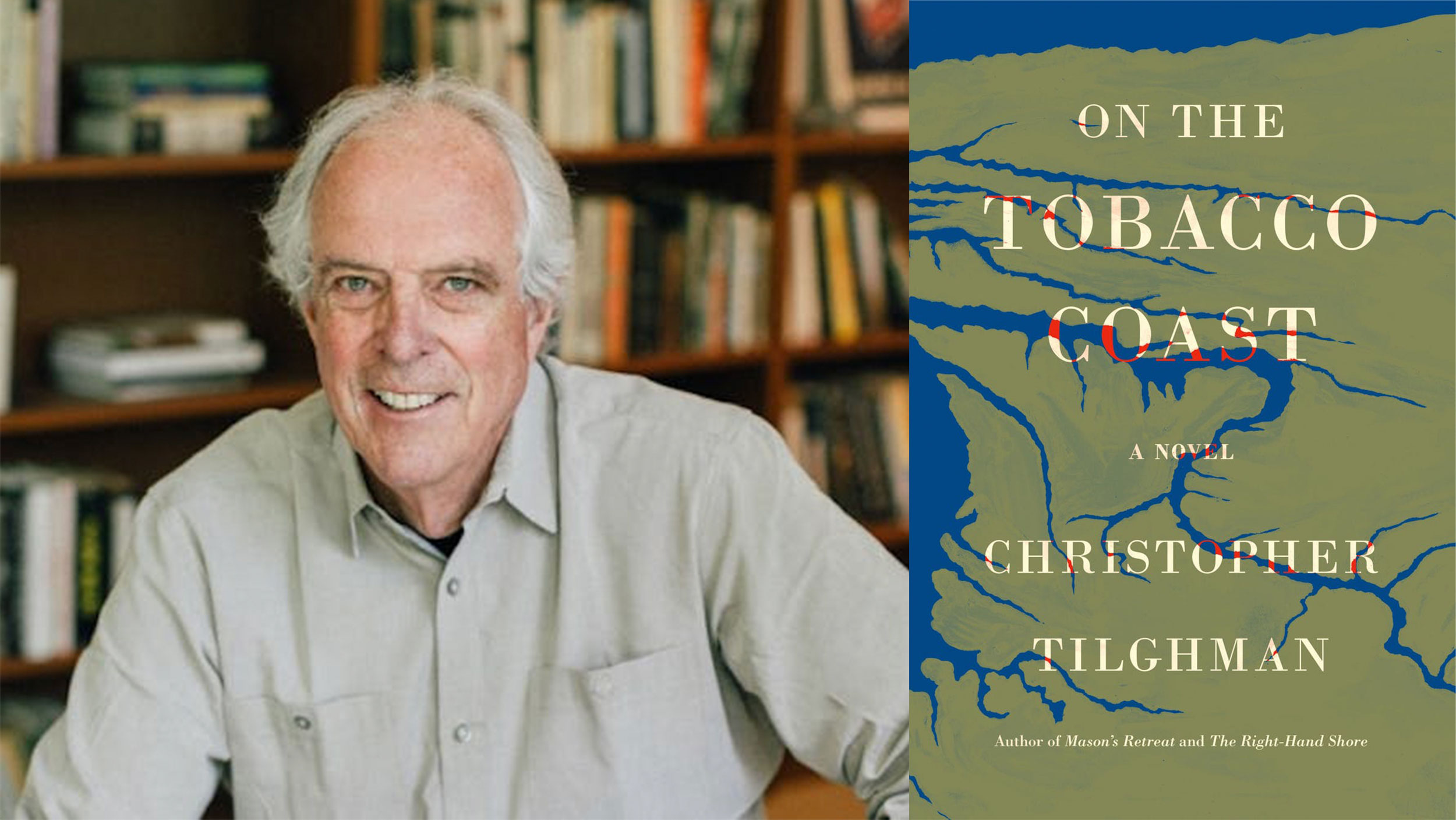

Christopher Tilghman and Jonathan Galassi discuss Christopher’s great Chesapeake saga, a story spanning four centuries of an American family, and Volume 4 in The Novels of Mason’s Retreat series, On the Tobacco Coast.

JONATHAN GALASSI: Chris, your novels about the Chesapeake are a project that has preoccupied you—with some detours—your whole writing life. It goes back to your wonderful first book of stories, In a Father’s Place which FSG published in 1990.

CHRISTOPHER TILGHMAN: Yes, it goes back to the first story in the book, “On the Rivershore,” which you published in a single letterpress volume as an advance introduction to my work. Calling it a promotion would hardly do it justice; it remains the handsomest volume in my library. People still mention it to me.

JG: There were other stories set in different regions, the Far West and New England. But the Maryland stories were at the heart of that collection. What accounts for the strong hold the region has on you?

CT: It’s really just the place, my family’s farm on the Eastern Shore of Maryland on which this is all based. My brothers and I grew up spending summers there; it has been at the center of my adult life. Everyone has places that matter to them, but not everyone spends thirty-five years writing about it. I admit, it’s a little obsessive.

JG: This land seems to speak to you, quite literally Or, as you say in On the Tobacco Coast, it haunts you.

CT: This has been one of the major themes running through all the books, the way what happens on the land becomes part of the land. In a sense, history is spatial, true history is the history of a place; even the most obscure patch of dirt can cry out. The lives that were lived there feel very real to me. I’m drawing in some cases on family stories, on the known history of the place, and some of my characters are lightly drawn from life and from fact. But even, maybe especially, the lives that are purely the product of my imagination seem rooted in the land. I have never tired of returning to them. Each time I conjure up a new character I get to see the Chesapeake landscape through new eyes.

JG: This all sounds vaguely Faulknerian? Is that fair?

CT: I can hardly deny it. There is a scene in On the Tobacco Coast that reenacts a scene from Absalom, Absalom! But what feels most Faulknerian to me about the project is not so much the material as the method: asking the same few questions over and over. What is family? What is the pull of the land? Why does history matter?

JG: Give us a sense of the scope of your story.

CT: After I published that first collection I intended to keep writing stories, but one of them turned into the novel Mason’s Retreat, which I published in 1996. The title refers to the farm itself; the ancestral place of the Mason family. The novel covers a tragic interlude in the three years leading up to the outbreak of the Second World War. I never envisioned that this was part of a broader saga. I moved on to a new collection of stories and another unrelated novel. But then . . .

JG: . . . . you returned. What brought you back?

CT: One thing that happened with the publication of Mason’s Retreat is that it unlocked a lot of local interest in my part of Maryland; there isn’t much fiction based on the Eastern Shore, after all. People told me stories that I had never heard before, a lot of history. The way the landscape influences the different cultures here began to make sense to me in a way it hadn’t before. I began to have an inkling of how a slave-holding society might try to evolve into something equitable. It didn’t happen, of course, but for a time it seemed it could. I wanted to capture all that. So The Right-Hand Shore goes back to the Civil War and describes the rise and fall of the farm during Reconstruction and into the twentieth century. It was hard going for me; I had to do a lot of research, which has never been my strength. I learned you can’t write historical fiction without knowing a lot of history.

JG: History, even in your contemporary short stories, has always seemed to me what you’re talking about.

CT: I see it now, but honestly, it took me a while to figure that out. I remember back in 1989 when you and Roger Straus took me to lunch, and Roger predicted that someday I would write some history. I was surprised to hear him say that. You mean, historical fiction? I asked. No, a work of history, of fact, he said. So far, he has been proved wrong, but in truth there are one or two small research projects percolating in my head right now. I might just write some history after all

JG: And then you took the story to France in Thomas and Beal in the Midi. You continued the story but left the farm behind.

CT: One of the main plot elements of The Right-Hand Shore is the love affair between Thomas, the presumptive heir to the estate, and Beal, the daughter of the Black orchard manager. This was a story I grew up with, but the real version ended with the suicide, in 1892, of the heir. I wanted a happier ending, so they marry surreptitiously, flee to France, and buy a winery in the south, in the “midi” as the French call it. I love France, I love wine. What could I do?

JG: And now you’ve come back from France, and back to the present day, with On the Tobacco Coast.

CT: Most of the novel takes place on a single day when the family—Harry Mason, his wife Kate, their three grown children, and assorted husbands, girlfriends, and grandchildren—gathers for a traditional holiday dinner. There is a day of summertime activities. The highlight of the dinner is the presence of Thomas and Beal’s great-grandson and his daughter, who have come from France to search for the origins of their American forebears, the white estate owners and the Black workers who made it all happen. .

JG: A domestic scene, then.

CT: Yes, on one level it is just a rather ordinary family with an unusually direct connection to its history. I had some fun with these people, types maybe, the twenty-year-old boy-man and his troublesome girlfriend, the young academic already bored with his university career, the cantankerous grandfather, the young writer of the sort I knew and loved from my many years of teaching creative writing at the University of Virginia. I wanted to give them the space to be serious, and the space for them to be funny, because that’s life.

JG: The “aspiring novelist confronting her pages” cuts close to home. What is she trying to write about?

CT: Eleanor is a recent graduate of an MFA program in fiction, and she started out to write a faux memoir by the wife of the family’s original immigrant, about whom almost nothing is known. The novel is titled The Exile’s Wife. Pages and scenes from this work appear at various moments in the course of the day—taken together they could be called a story-within-the-story— which allows the reader to go even further back in time, to the settling of the New World. In this way On the Tobacco Coast serves as both my conclusion to the sequence, and the beginning of it.

JG: But she has trouble with the book and can’t pull it off. Her anguish about it is one of the motifs of the novel. What is her problem?

CT: Her problem is history. She is determined to give a place in history to this forgotten woman, to describe what must have been an almost unimaginable life, but the more “agency” she gives her, the more Eleanor must confront her subject’s involvement in the crimes that attended the founding of the American republic and whose effects continue today.

JG: The extermination of the Indians, enslavement of Africans, despoliation of the environment, to name a few of those crimes?

CT: My character Kate, the mother of the latest Mason generation, has only partially bought into all this generational business. She asks her husband, “What crimes against humanity did your family not commit on this farm?” The answer is, not many. And so the family must contend with this fact because these events haunt the room. So the question is what should the Mason family think about this, what are they willing to do about this. This is the main subject of the conversation at the dinner, a long scene that serves as the climax of the story.

JG: What do they decide? What is the conclusion?

CT: Well, spoiler alert to any readers out there, but they don’t decide or conclude anything. Each of the characters at the table has their own sense of their relationship to this history. Each has their own sense of obligation to the living, and to the dead. For the Masons, the past is both a burden and a privilege; either way they, and we, have been told we must atone. The fact that they are Southerners—in terms of history, the Eastern Shore of Maryland is part of the Deep South—lays a particular regional onus on them. But why just them, when—as one character argues—everyone in this country is implicated; the land itself knows that it was stolen.

So they muddle through. In the end, climate change has as much to do with the denouement of these discussions about the farm as anything; whole swaths of the Eastern Shore are simply washing away as we speak. Living in America today seems to be about choosing a side, America today is an unwinnable game, and the arena for this contest is, more often than not, our history. My book is about being in the middle, where so many of us are.

JG: The order you wrote them in bounces around a good deal in time, the “sequel” to Mason’s Retreat is in fact, a “prequel.” All four books telescope forward and back in time, overlapping and intersecting with the characters and events from other volumes. Why did you write them in this order?

CT: The telescoping in time reflects both my impulses as a storyteller and my sense that the past, the present, and the future exist within us at every moment of the day. Indeed, this sense of time emerges as a major theme in On the Tobacco Coast. As to the question of order, as I said, I never set out to make this a multi-volume saga; I just wrote them, with other books intervening, when the material became interesting to me again.

JG: if a reader might choose to read all four, in what order should they read them?

CT: I hope each book stands on its own, but if a hypothetical reader wanted to do such a thing, I would suggest the books be read in the order I wrote them, because that reflects my thinking about the material as it evolved over a thirty-five-year period.

Christopher Tilghman is the author of two short-story collections, In a Father’s Place and The Way People Run, and four previous novels, including Thomas and Beal in the Midi, The Right-Hand Shore, and Mason’s Retreat, which recount the connected stories of the Mason and Bayly families. He is a professor of English at the University of Virginia and lives with his wife, the novelist Caroline Preston, in Charlottesville, Virginia, and in Centreville, Maryland.