Anne Fadiman, author of The Wine Lover’s Daughter, and Cullen Murphy, author of Cartoon County, embarked on an epistolary exchange to probe their shared experience of bringing their fathers back to life through writing. Fadiman’s father—literary critic, editor, and radio host Clifton Fadiman—had a passion for wine that shaped his outlook on life. Murphy’s father was a cartoonist and a member of the influential Connecticut School. In this exchange, Fadiman and Murphy prompt self-reflection and scrutiny in one another, discussing what it’s like to remember those we loved most, the poignant process of exploring a parent’s life, and whether their fathers would have liked their books.

October 24

Dear Anne,

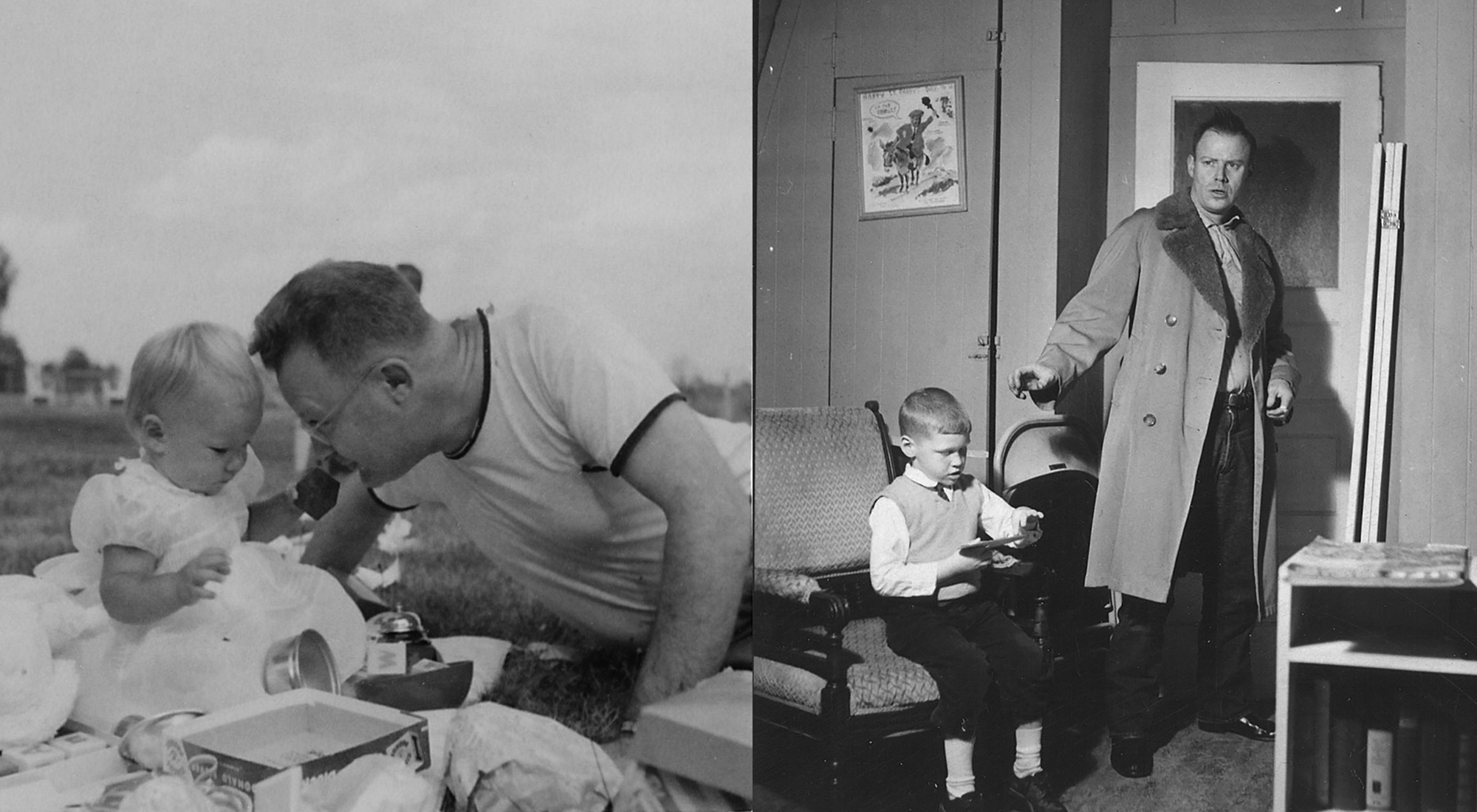

I finished The Wine Lover’s Daughter on the most beautiful New England weekend of the fall, and somehow the autumnal surroundings seemed wonderfully apt for your memoir. (For any memoir, really.) You and I have both written books about our fathers—in both instances, people to whom we were powerfully drawn, and in both instances people of a certain stature in their worlds—worlds that have largely vanished. Mine was a cartoonist who lived in the midst of a large and eccentric cartoonist community that flourished in Connecticut in the latter half of the twentieth century. Yours was a literary impresario and cultural jack-of-all trades whom I first encountered—remotely—when I was about 13 and joined the Book of the Month Club, where he was on the editorial board. “Recommended by Clifton Fadiman!” I’m not sure I ever ran down the stairs shouting those words, but it’s the feeling I had in my heart as I browsed the book selections. The very name seemed to roll off the tongue, conjuring images—which I now know to be mistaken—of some Brahmin grandee with a bloodline that that could be traced through the Fly Club to Plymouth Rock. Brooklyn, actually, you say. A child of Russian immigrants. But then Columbia in that epochal interwar era, and it all makes sense.

John F. Kennedy famously deflected some regrettable behavior by Joe, the patriarch, with the words, “We all have fathers, don’t we?” There’s a strong current in family memoir (Mommie Dearest) that runs to the malign. Cartoon County and The Wine Lover’s Daughter are a counter-current. I remember when Arianna Huffington published her biography of Picasso—no paragon as a family man—and gave it the subtitle Creator and Destroyer. My father saw the book and said to me: “When you write my biography, I want the subtitle to be Creator and Provider.” Funny . . . but he had a point. He had eight children to provide for, not to mention create (which I hope was a little easier). In my book I’ve tried to evoke the odd world of cartooning that he inhabited, and the often other-worldly experience of watching his calloused hand bring images to life. He is at the center of this memoir: unschooled but well-read, shrewdly opinionated, gentle, given to puns, proud of his craft. Or maybe “center” isn’t the right word—it’s more as if his branches arc over all of it. Which is why I love the term you use for yourself—“oakling.” I’m one too.

Cullen

• • •

A publicity still of Clifton Fadiman for NBC’s Information Please.

October 24

Dear Cullen,

Welcome to the Oakling Club.

My term “oakling” comes from an 1833 review of a volume of poetry by Hartley Coleridge, the son of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Imagine trying to be a poet if you had STC as your father! The reviewer conceded that Hartley was a pretty good poet, but then cited an old adage: “The oakling withers beneath the shadow of the oak.”

Whew. The implication is that people like you and me—the children of well-known parents—are basically doomed. Fortunately, I don’t think we are. Hartley Coleridge may have ended up as a drunk who spent too many days in alehouses and too many nights in ditches, but you and I seem to have survived our oaklingdom without undue withering.

I think of oaklings particularly as the writer children of writer parents. My father, of course, wasn’t just a writer. At twenty-eight, he was the editor-in-chief of Simon & Schuster; at thirty-four, the host of Information Please, a radio quiz show to which more than a tenth of the population of the United States tuned in every Tuesday night. I suspect that one reason I managed to become a writer even though such a formidable shadow loomed overhead is that my father was nearly fifty when I was born. Had I entered the picture at the height of his fame, finding my own place in the world would have been a heck of a lot harder. But you were the writer son of a cartoonist. By choosing a different medium, you insulated yourself from being told you were a chip off the old block. (By definition, chips can never be as big as blocks.) You even collaborated with your father as the writer of his Prince Valiant strip. If I’d ever collaborated with my father, my own identity as a writer would have gone poof.

One of the greatest pleasures of writing The Wine Lover’s Daughter was quoting from my father’s out-of-print essays; as I typed out his sentences, it was like hearing his witty, sophisticated voice right up next to my ear. Your mode of quotation was visual. One of the most wonderful things about your altogether wonderful book was the illustrations: cartoons, drawings, paintings, photographs. What an artist your father was! How did you find all that marvelous work? Harder yet, when you were deciding what to put in Cartoon County, how did you make your choices?

Anne

• • •

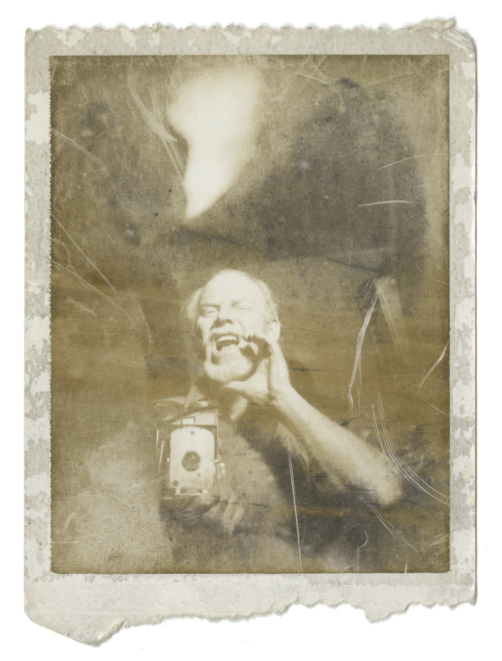

John Cullen Murphy with his camera.

October 25

Dear Anne,

How to make choices? You raise a good question. “Choice” has a better reputation than it deserves, and “constraint” a lesser one. My father liked the fact that a comic strip had to be done in specific panels of a specific size—it took a universe of possibilities off the table, he maintained, and freed up his creativity. That said, he didn’t choose what to save from among the artifacts of his lifetime—he saved everything. I have second-grade tests from his boyhood in Chicago.

But I’m glad he saved all those Polaroid pictures he took of himself, starting in the late 1940s. Between Big Ben Bolt and Prince Valiant, my father drew upwards of 100,000 human figures in his comic strips. It was a real time-saver to dress up in costume, gather yourself into the desired pose, and then, with the help of a pneumatic plunger, snap a photo that could guide you as you penciled and inked. Or, later, have me or one of my brothers or sisters snap the photo. The result is a kind of preposterous archive spanning half a century—my dad in strange costumes, gradually growing older. A beardless young man turning into Don Quixote. He wasn’t alone among his cartoonist friends in taking pictures. Stan Drake, who drew The Heart of Juliet Jones, was another. Dad was probably alone in saving them, though. And of course he saved all his artwork, which was everywhere—on the walls, in drawers and closets, up in the rafters.

Your own father was different. As you describe it, he shucked documentary encumbrances as he went along—which makes what lives on all the more intriguing. Two moments of discovery bookend The Wine Lover’s Daughter. One, at the beginning, comes when, as a girl, you stumble on his essay “Brief History of a Love Affair.” (And it’s not about what you think, to your momentary regret.) The other, at the end, is the discovery of the Cellar Book. I love the way you describe what it was like to open it for the first time. You compare the experience to opening a bottle of wine—finding “a life that had deepened while it bided its time.”

Cullen

• • •

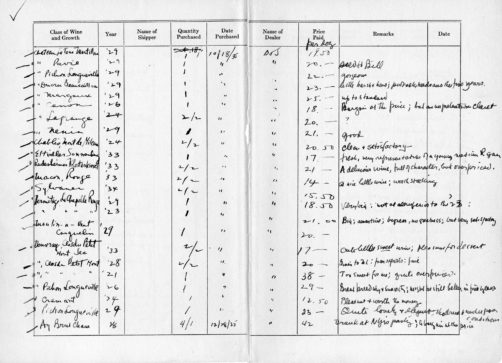

A spread from Clifton Fadiman’s 1935 cellar book, a record of his wine purchases.

October 25

Dear Cullen,

Ah, discovering my father’s Cellar Book! My Rosebud moment.

My father loved wine more than anything in the world aside from books. Both of them were powerful symbols of the patrician world he yearned for when he was growing up over his father’s drugstore in Brooklyn, sharing a bed with his two brothers and looking out the window at muddy streets that smelled of horseshit from delivery wagons. (He would have been delighted that you imagined him a Brahmin grandee. He also would have burst out laughing.) Eight years ago, it occurred to me that I could say pretty much everything I wanted about my father’s character and his upward social arc through his relationship with wine, starting with the first, magical glass of cheap white Graves he drank in Paris in 1927 while retrieving his first wife from an Italian count (or a baron—he told the story both ways).

On a warm summer night after I was well into the project, I stumbled upon a folder labeled WINE MEMORABILIA. I’d inherited my father’s files after his death, but this particular folder had sunk lower than its neighbors, and I’d never noticed it before. Inside was his Cellar Book, the record of his wine purchases, starting in 1935, two years after the repeal of Prohibition. It’s impossible to describe what it felt like to see his familiar handwriting spelling out the sacred vintages he’d dropped into Fadiman dinner-table conversation like the names of the saints: Château Margaux. Château Haut-Brion. Château Lafite Rothschild. Chambertin. Montrachet. Grands Échézeaux.

I might add that the Margaux—1929, no less: a great year—cost $25 a case, or $2.08 a bottle.

A bargain, even if you adjust for inflation. Nonetheless, I discovered that on his first day as a wine collector, my father bought nine hundred and eight bottles. Which leads me to the subject of money. You and I both grew up taking for granted the notion that one could actually make a living from creative work: enough, in my father’s case, to fill a wine cellar, and in your father’s case, to buy a house and a barn and a studio in suburban Connecticut—and to support eight children.

Anne

• • •

Pen-and-ink sketch by Mort Walker and Jerry Dumas, the team behind Sam and Silo. The eponymous characters float above a landscape of cartoonists.

October 26

Dear Anne,

Always an interesting question, money, and one that in our family we were taught not to ask, much less answer. It was just not a proper subject. I know that things were sometimes tight: on occasion my father would take on outside work of various kinds—illustrating books and even painting covers for Mets and Red Sox programs. (My mother’s parents were never convinced that what he did was “work” in the first place.) But we got by, and the children were shielded from worries. Looking back, one of the remarkable things about the gag cartoonists and comic-strip cartoonists in Fairfield County was that they really could cobble together a living by their wits and live an ordinary middle-class life at the peak of the American Century, and in places like Greenwich and Westport. In this they were a lot like the writers and intellectuals of your father’s generation, who were able to live comfortably by writing articles for Dissent and Partisan Review and Commentary and The New Republic and other small magazines—a preposterous idea today.

The lesson we took away, all of us in the family, was that what you earned was less important than what you did—and that what you did was a matter of personal invention. We inhabited a social circle whose members, in different ways, had figured out how to live as they pleased by drawing pictures. Crockett Johnson was one of these Fairfield County cartoonists, and his classic children’s book Harold and the Purple Crayon was an almost literal expression of the idea that you could draw your own reality, and it would turn out to be real enough. It sounds highfalutin, and no cartoonist would ever have put it this way, but each had a certain faith in his inherent gift. Without that, how could you have joined scores of fellow cartoonists in Manhattan on “look” day—every Wednesday—when you tried to sell gags and sketches at the many magazines (as there were back then, in the 50s and 60s) that published cartoons? There was camaraderie, to be sure, but there was also rejection, and the fearful knowledge that your family depended on some editor liking what you’d penciled on a piece of paper.

My mother was in on this secret—the bedrock insistence that you should trust what drives you—and it’s something that my parents passed along to all their children. That’s our trust fund, I guess.

• • •

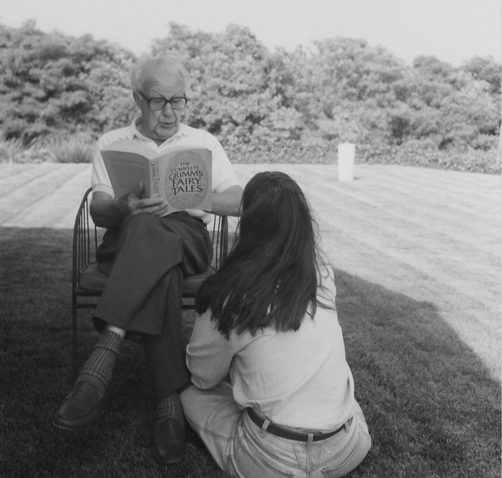

Clifton Fadiman reads to Anne, 1984.

October 26

Dear Cullen,

I underlined your mother’s instructions to the eight of you on the subject of holiday gifts: “Make something.”

The legacy we inherited from our parents—that we could, should, and perhaps even must “make something”—was what enabled us both to become writers and editors. You and I didn’t just hear about creativity; we witnessed it daily because our fathers worked at home, yours in a studio beneath an apple tree, mine in a study equipped with a Ping Pong table at which my brother and I were permitted to play (loudly) while he was writing. And part of that legacy was the great material our fathers left us because they were both so damned interesting.

Plowing through that material—not only my memories but my father’s essays and reviews and forewords and afterwords and letters, along with hundreds of photographs of him with me when I was small and then with my own children when they were small—was both glorious and painful. Part of the pain came from missing him, but part came from the evidence of his many imperfections. When I Googled old newspaper stories about him, I repeatedly winced at his remarks on gender, which included “Women are not as good at conversation and they know absolutely nothing about wine.” You might call The Wine Lover’s Daughter an attempt to refute that statement.

A reader told me last week, “Your father would have loved your book!” He was wrong. My father might have enjoyed parts of it, but he bore no more enthusiasm for the American compulsion to share intimate details than he did for bubblegum, dips, self-help books, off-rhymes in advertising jingles, and actors who omitted consonants. He would have hated my chapter on how, despite his success, he always felt like a fraud—a man who had been admitted by mistake to a gentlemen’s club and lived in fear of being booted out the service entrance. Or the one about how fervently he wished he weren’t Jewish. Or the passage about his infidelity.

What would your father have thought of your book?

Anne

• • •

Mort Walker’s fortieth-birthday party, 1963. John Cullen Murphy is in the front, second from the right.

October 27

Dear Anne,

Well, to begin with, he would have liked yours. My father was impatient with the term “public intellectual,” which seems to have arisen mainly because intellectuals aren’t woven into public life the way they used to be. But he loved the kind of person your father epitomized, and he loved the culture (now diminished) that kept a place at the table for them. In his spare time, when he wasn’t drawing comic strips, he painted striking oil portraits of people like Chesterton, Sandburg, and Shaw—writers who were active in the world. You have to pinch yourself when you recall that figures such as your father (and Bennett Cerf) were on nationally broadcast quiz shows, where smart conversation was prized. Ted Weeks, the longtime editor of The Atlantic in the mid-20th century, had a weekly half hour radio program—Meet Mr. Weeks—on NBC; inconceivable now. A show like the BBC’s My Word, featuring those dotty amateur linguists with their over-evolved Oxbridge accents, was catnip to my father. The idea that the Great Books could become something of a national obsession for a while was something he applauded—for other people—even if he knew the books would remain with their spines uncracked in that special bookcase you could buy. There was an aspirational element that he liked as a national trait. Dwight MacDonald gave all this the back of his hand a lifetime ago, in his essay “Masscult and Midcult,” but look around: we could use a booster shot of either, or both.

As for his opinion of my book about him: well, I do have one clue. About 20 years ago I wrote a magazine article about my father’s experiences as an artist during World War II, and ventured my own thoughts about his growing maturity as a person and his grace as an artist during those formative years. When the article appeared, he called to thank me, and then said, “I’m lucky to be able to read my own obituary.” There’s a slight undercurrent there, but it’s about life itself: happiness comes with unease. My father didn’t put on airs, except ironically, but I think he would have liked the fact that the cartoonist community he cherished had been preserved in memory. It was a big part of his life—and the work of its members was a big part of the country’s life. (Take that, Great Books!) The small things about that community—the smell of pencil shavings, the sound of a brush in water—are the first to vanish from memory, and the hardest to recover, and they’re some of what I wanted to restore.

When we ended phone calls, my father would often use an old Bob and Ray line: “Hang by your thumbs.” To which I’d give the reply: “Write if you get work.” He would have understood that, more than anything else, the book is a love letter.

Cullen

• • •

Anne Fadiman and Clifton Fadiman before his 80th birthday party.

October 27

Dear Cullen,

So My Word was catnip to your father? No wonder you became such a wordsmith yourself. In fact, some of my favorite parts of Cartoon County are about the words cartoonists use, an enchanting argot that was entirely new to me. You and I are almost exactly the same age—you were born in 1952, I in 1953—so it’s not an impossible stretch to imagine that at the same moment my father was dropping the name of a premier cru Bordeaux into the dinner-table conversation, your father was saying something about a “squean” (which I now know is the cartoon starburst that means a character has had too much to drink) or a “plewd” (the bead of sweat that means he’s working hard) or an “indotherm” (the wavy line that means the pie he’s about to eat is hot).

The years we spent researching and writing about our fathers’ lives (with plewds surrounding our heads) were, I suspect, not just a way to write books we hoped others might wish to read but an attempt to bring two dead men, Lazarus-like, back to life. Your father’s character was so vivid in your pages that I often felt you and he were having a conversation—or, perhaps, that he was still providing the pictures while you provided the words, as in your old collaborations.

My father once said he was so non-religious that “it is as though the Great Monosyllable were a nonsense word, like xybyabt.” Like him, I don’t believe there’s any spiritual communication between the living and the dead. But when I wrote about him, I could see him—bent over a galley from the Book of the Month Club; writing in tiny, crabbed handwriting with a fountain pen; leaning forward gleefully as he told a story (always self-mocking) about his Brooklyn childhood; ecstatically narrowing his eyes as he took the first sip from a really good bottle of wine.

Thank you for letting me see your father too.

Hang by your thumbs,

Anne

Anne Fadiman is the author of The Wine Lover’s Daughter, a memoir about her father (FSG, 2017). Her first book, The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down (FSG, 1997), won the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and the Salon Book Award. Fadiman has also written two essay collections, At Large and At Small and Ex Libris, and is the editor of Rereadings: Seventeen Writers Revisit Books They Love (all published by FSG). She is the Francis Writer-in-Residence at Yale.

Cullen Murphy is the editor at large at Vanity Fair and the former managing editor of The Atlantic Monthly. He is the author of The Word According to Eve, Just Curious, and God’s Jury. He lives in Massachusetts with his family.