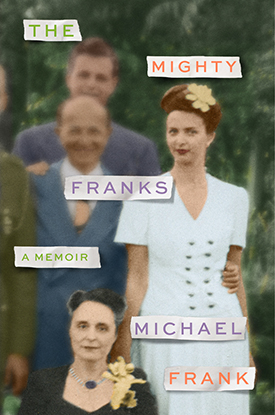

The visual artist Joyce Kozloff and I were surprised to discover that we have both completed projects inspired by the material leavings of our childhood worlds—in Joyce’s case found, in my case (mostly) lost. Girlhood was Joyce’s recent exhibition at the D.C. Moore Gallery in Chelsea; my memoir, The Mighty Franks, was published in May. Last month, Joyce and I sat down in her SoHo studio to discuss the different ways memory can work on tangible stimuli, not only to recapture the past but to transform it into something altogether different and often unexpected.

—Michael Frank

Frank: The past is always with us. True, false, in between?

Kozloff: Truer than we often know—or want to know. In your case, inescapably so. Even when someone tried quite literally to throw your past away.

Frank: You’re referring to what happened in September 2010, on the day after my uncle, the screenwriter Irving Ravetch, died. In the space of a single morning, my aunt, Harriet Frank, Jr., his writing and life partner of nearly six decades, arranged to have his closet completely emptied of all of its contents.

Kozloff: It wasn’t an everyday closet . . .

Frank: The room was about 10 by 12 feet, the size of a New York City bedroom. It was where my uncle kept his conscientiously curated clothes (he was a medium-level peacock), but more importantly, it also served as a kind of three-dimensional, ever-accruing diary for him. He arranged letters, manuscripts, photographs, paintings, and personal objects on carefully appointed shelves and in drawers and boxes. When I learned that my aunt had erased all these physical traces of my uncle’s life, I was overcome with a desire to begin writing what eventually became The Mighty Franks.

Kozloff: Your uncle needed to find a way to hold onto his identity under the assault of your aunt’s larger-than-life personality. What was your equivalent?

Frank: I didn’t have a room, but I did have habits. I observed and I remembered. There was also the example of that closet, which was a form of gentle—you might also say visual—defiance.

Kozloff: Your stimuli were eradicated, and so you had to retrieve them in language.

Frank: That sounds right. You, on the other hand, had the opposite experience. Traces of your past emerged out of the mists of time.

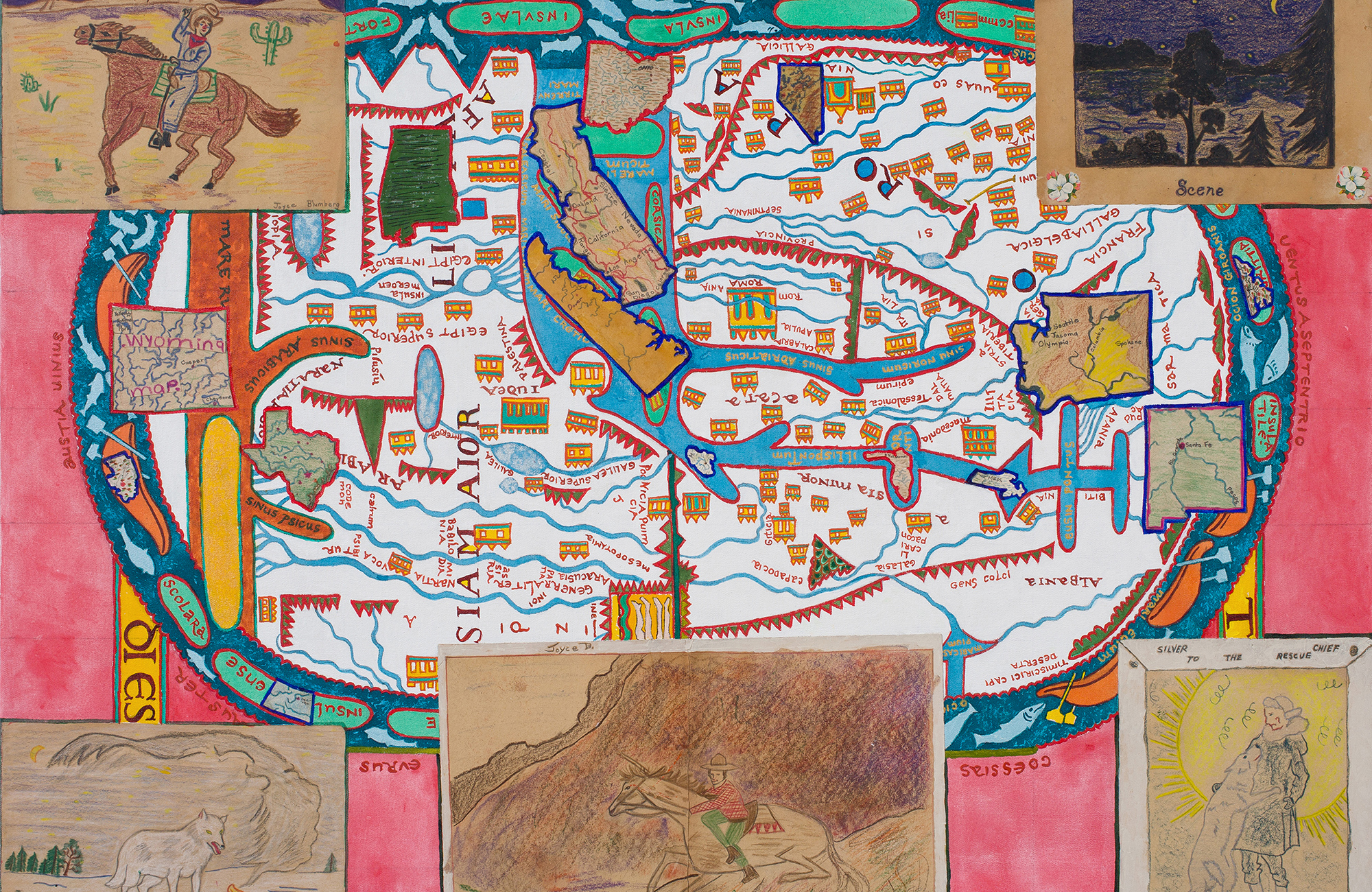

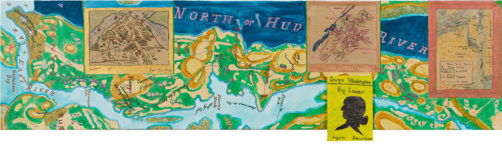

Kozloff: When my mother died in December of 2014, my sister-in-law and I spent nearly a year clearing out my parents’ longtime New Jersey home. On the very last day, crawling into the eaves of a dusty attic, I found a rusted filing cabinet lying on its side. In one of its drawers my mother had saved a cache of my childhood drawings that I had completely forgotten. Many were maps made when I was between 9 and 11 years old.

1776 by Joyce Kozloff

Frank: Maps! When you have spent something like the last 25 years making cartographic work. Were you surprised?

Kozloff: Dumbfounded. I remember very little about my childhood. The drawings had vanished from my memory. I could never write a book like yours.

Frank: So this was like meeting yourself all over again—your unedited younger self, contained in the time capsule of a filing cabinet drawer. Not many of us have the chance to do that, in life. Did you feel any connection to the child Joyce?

Kozloff: Artistically, yes. Joyce Blumberg already had a compulsive attention to detail, she appropriated—at that age, though, copied is a more fitting word—from other sources, and was fascinated by history. Is there a parallel meeting of your younger self in your uncle’s closet?

Frank: My uncle’s closet contained pieces of my past but much more so my uncle’s, along with evidence of our shared family life. I should probably say that my aunt and uncle were my parents’ siblings—that is: brother and sister married sister and brother. Having no children of their own, my aunt and uncle sought to “borrow” me as a child. They taught me how to see the world, meaning to see it as they did, ideally. The lost objects in the closet gave me a way to begin to construct an alternate version of the story—to find my own way in. I started with the things, which led to the places, which led to the drama—and there was quite a lot of it—and in the end it accrued into my version, my vision. I wonder if the drawings played a similar role for you in these recent paintings.

Kozloff: My work has not, historically, been autobiographical. I didn’t know I was going to do anything with these maps right away. First I spent months reading through a mountain of family letters and memorabilia I also found in the house. A lot of it was boring, but there were bits and pieces—glimmers, family secrets—that led me to a different understanding of my past.

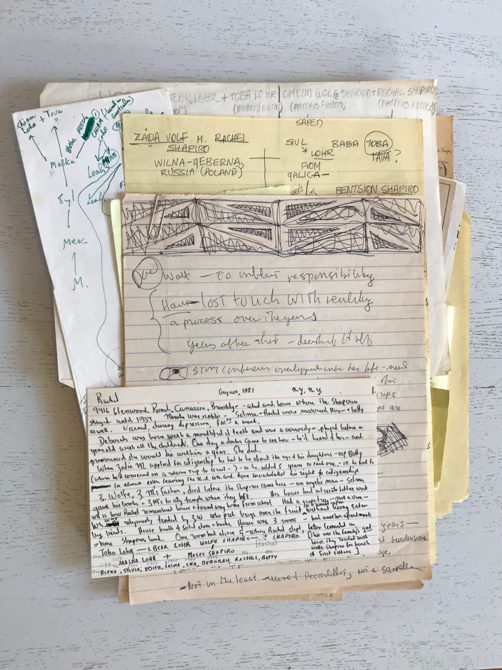

Notes from Michael Frank’s collection

Frank: So you immersed yourself in your family history, and then you began building paintings around your childhood drawings. There’s no connection?

Kozloff: I’m recognizing that now.

Frank: The drawings you made as a child feel very disciplined and even rigorous. Was someone encouraging you?

Kozloff: I drew from a very young age. I drew “girly” stuff, pictures of women out of fashion magazines, out of Louisa May Alcott novels for book reports in English. I received a lot of affirmation at school. But later, in high school, when I came home and announced that I was going to be an artist, my parents were appalled. They wanted me, like my mother, to be the wife of a lawyer, to lead a safe, conventional, middle-class life.

Frank: So after reviewing your family’s past, you reached back to embrace—maybe also to celebrate?—this extant evidence of your early artistic practice and decided to address it as the visual artist you are today. There seems to be something at once tender, victorious, and valedictory in this gesture.

Kozloff: Max [Kozloff’s husband, an art critic and photographer] jokes that in these new paintings I am competing with a young talented artist named Joyce Blumberg. I think of it more as a conversation. It’s as if the two of us have met, finally, after years of not knowing each other.

Frank: You two meet, but Joyce Kozloff directs that conversation.

Kozloff: At first I felt obliged to use Joyce Blumberg’s work as I found it, in a pristine form. Then some friends came and looked at what I was doing and said it felt too respectful, that I hadn’t integrated the girlhood drawings. That’s when I started having more of a dialogue. I cut into them; I painted over them; I used them to collage into related and unrelated maps, the kinds of things that have compelled me now for decades. Gradually we met on a middle ground.

Frank: Were these maps personal to you? Were they chosen for associations you had to their subject matter?

Kozloff: I don’t think so. Clearly I copied the maps, like the book report illustrations, from books. Why do you ask?

Frank: Because when I was well into The Mighty Franks, I came across a box of notes I had begun making when I was so young I still didn’t have adult handwriting. I took down stories from my surviving great aunts and uncles, I annotated family trees, I wrote down addresses, facts, dates. I had absolutely no idea at that time what I was doing, except that—on some level—I was trying to understand the how, and the why, of my family.

Kozloff: You were already writing but didn’t know it.

Frank: I was onto one of my subjects—my family—before I knew where all that curiosity was leading. In your case, the young Joyce was intuiting the future Joyce’s mapmaking.

Kozloff: Well, that’s not quite how it happened. After doing public art for decades, I was returning to the studio and trying to figure out my next steps. With those projects I would customarily start with the elevations and floorplans of the site. I began thinking of the plans as maps into which I would weave and layer content, often local imagery and patterning. The work in the studio started there. At first, I thought I would make a few cartographic paintings, but over the years, I kept having new ideas, because they can contain such a combination of cultural, historical, geographical, and political information.

Frank: They often tell a story.

Calm Sea Rough Sea by Joyce Kazloff

Kozloff: Yes, and they hold a distinct point of view. Whoever maps, controls. When the Europeans colonized, they seized territory through mapping. They renamed places, planted their flags, and took over. Then they would return to Europe; engravings would be printed and translated, errors would be made and copied, local traditions obliterated.

Frank: Whoever maps, controls. That feels very resonant. I think it has a personal application, too. Even in that small, intimate, and often insidious country known as family, whoever describes the lay of the land defines it. He or she assumes the power. I essentially had to map—remap—my childhood in order to understand it.

Kozloff: And claim it for yourself. Narrative as map-making—through time rather than place.

Frank: To inhabit your own life, maybe you have to map your own path first.

Kozloff: Even if you don’t know where it will lead you, it’s one way to develop an authentic voice. And maybe you’ll end up discovering that voice was there all along.

Michael Frank’s essays, articles, and short stories have appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, Slate, The Yale Review, Salmagundi, and Tablet, among other publications. His fiction has been presented at Symphony Space’s Selected Shorts: A Celebration of the Short Story, and his travel writing has been collected in Italy: The Best Travel Writing from The New York Times. He served as a Contributing Writer to the Los Angeles Times Book Review for nearly ten years. He lives with his family in New York City and Liguria, Italy.

Joyce Kozloff is an American artist whose politically engaged work has been based on cartography since the early 1990s. Her paintings are included in the collections of The Metropolitan Museum, The Whitney Museum of American Art, The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and elsewhere.