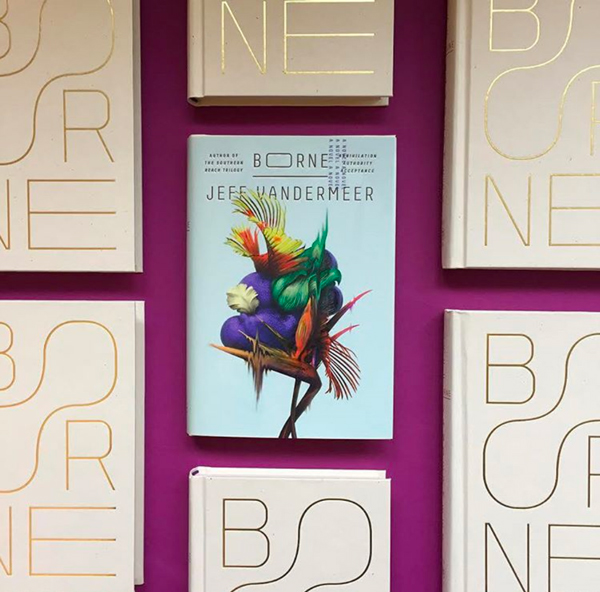

Jeff VanderMeer’s Borne is an unusual kind of coming-of-age story—it isn’t a human that grows up, but rather a sentient, shape-shifting bit of biotech, raised by a young woman in a city ravaged by corporate greed. The book was met with rave reviews—The New York Times Book Review called it “a promise that what emerges from the twenty-first century will be as good as any from the twentieth, or the nineteenth.” VanderMeer joined Jac Jemc, author of the forthcoming The Grip of It, in conversation at Volumes Bookcafe, for a conversation on the interplay between reader and writer, environmentalism, and of course, flying bears.

Jac Jemc: I would love to start by going back to the origin of the story. You’ve mentioned that Neo, the cat was an inspiration for Mord. And I wanted to ask, because a friend had tipped me off that Mord actually appears in an earlier story, “The Third Bear,” that came out in 2007, is that right? Clearly, Mord has been with you for a long time. What’s the relationship of that Mord to the Mord that shows up in Borne?

Jeff VanderMeer: I tend to do proto-stories that are from alternative universes from the novel I’m working on. But Mord has also had a life online. Mord actually ran for president twice, on Carnivore Party tickets, and pledged to devour traditional politicians and whatnot. So there are actually campaign posters for Mord floating out there. Early on as I was kind of field testing his character, I would replace my icon with an icon of a giant bear on Facebook, and then, in all caps, with Mord referring to himself in the third person, basically had Mord make outrageous statements about wanting to devour people. It was amazing how many people would start arguing with Mord. And Mord was basically like, come here so I can swat your head off and eat you. Mord even published children’s poetry some people were offended by, because it was pretty much about being a carnivore. So there was that aspect. It was actually very entertaining to do as a kind of social experiment, but it also kind of gave me some insight into his thought process. And then our cat, Neo, a giant, twenty-pound cat, who I nicknamed Massive Attack, because when we first got him, he would be on the mantel above my head at night and he would do a one-eighty and land on my chest, which was not very good for a middle-aged man’s health. And he just has these amazing broad shoulders. Every once in a while he’ll just get a wild itch and he’ll just run around the house, and he’s so loud it sounds like galloping. And he’ll just run up and down the cactales and everything else. And so there were certain attributes of him—also, his attribute of eating geckos, which I don’t like very much— which I actually gave to Borne. So Neo’s been a big influence. Sometimes you can do that, you can take just ordinary things from everyday life and use them that way.

JJ: So much of the worlds that you’re building in your fiction seem so closely tied to the natural world and to environmental concerns that we have right now. When do you allow yourself to depart from those concerns, and how much do you try to stay close to the biological truths?

JV: Yeah, that’s a really good question. For The Southern Reach trilogy, I stayed a lot closer to biological truths, although I got in trouble from several snake owners for calling snakes “poisonous” instead of “venomous.” But anyway, that series is a lot closer because of its realist vein. It was science fiction written from the viewpoint of the uncanny, in a way. And this novel is really science fiction written from the viewpoint of Moebius, Jodorowsky, fantasy, and things like that. So what you’re looking for is to get some kind of psychological truth across about the behavior of the animals. And you have some leeway, because you’re also talking, in many cases, about biotech: animals have been transformed in some way. Also, I really believe that if you’re going to write apocalyptic fiction or post-apocalyptic or dystopian, you should also have some kind of contrast between the grimness of whatever you’re portraying and the world around it, because even in situations today where people are in profoundly terrible situations, they find that thing that brings some brightness into their own lives. There’s a need to document that as well.

JJ: You do such an amazing job of creating these worlds that are so fully formed that you can really stress test them and everything works out so clearly. And I wonder, have you figured out some best practices? Because as you add more and more to the world, that just creates more for you to keep track of and to keep an eye on, right?

JV: Well, it varies from book to book, because I really believe that even in third-person narratives that there’s no such thing as setting, there’s just the setting that the character sees. It’s always coming through the character, and so that gives me some guidance as to what to put in, what not. I went back and counted the animals that are in Borne and there are a hundred and twenty. And then I did a bestiary for like thirty-five of them, like the backstory for them, and I realized there was so much that Rachel didn’t know. And also the texture is very different in Borne; I wanted the animals and people to stand out in stark relief.

I really believe that even in third-person narratives that there’s no such thing as setting, there’s just the setting that the character sees.

JJ: I love that idea of the setting of a story being fallible in some way. Especially in Borne because, toward the end of the book, you talk about the way that collective memory works and the way that if the clutch of memory fails then maybe that place can cease to exist as well. In one of the final scenes, the point of view zooms out from Rachel and allows us to fully acknowledge that while what we’re seeing is Rachel’s point of view, the rest of the ways you can look at what’s happening—that is what creates the true memory. And it’s such a lovely way to manipulate point of view. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything so sure-handed. And I was thinking about The Southern Reach and the way that we’re allowed to understand that world through the points of view of the different characters, but in Borne we really only get Rachel’s point of view until that final moment. Was working on Borne from that singular point of view a reaction to the way that you had built our understanding of Area X?

JV: Well I don’t like to inhabit the same place twice. I don’t like to write the same novel twice. Even the three novels in The Southern Reach are very different in their structure. I mean, the second character, Control, doesn’t know birds from a hole in the wall and it shows in how the narrative is. But, with Borne, I had the sense that Rachel intermittently feels like she is the chronicler of events that are greater than herself, so some of it comes from that, and one of the challenges was moderating the tone between the very personal and the informal. But then, I think what you’re also talking about is, there’s another character, who I didn’t think would directly say anything to anybody about his situation, and that the only way that he would do it would be indirectly. That creates a kind of opening to introduce another viewpoint, so to speak, without giving too much away. And then, of course, Borne gets to express himself, because at one point Rachel finds what is basically his diary.

JJ: Laura Miller’s review of Borne in The New Yorker talks about the book’s themes in relation to the idea of parenting and the way that we nurture things into the world and how, even when you really have the best intentions, how things can go awry. How Borne when talking to Rachel can repeat back exactly her words but they can still be misunderstood. I like that as an echo of parenthood, but I think it’s also a really great metaphor for any act of creation, and especially for writers. Thinking about the way that Annihilation is being adapted to film, or maybe just thinking about the way that Borne has been allowed out into the world now, what is the process of letting that act of creation free for you and letting someone else have control?

JV: For the longest time, very early on, I was a very arrogant young writer who didn’t understand the space that a reader needs. That in the imaginative act if you can create interesting spaces for the reader, they’ll reward your text by bringing something to it that gives it additional life. I really thought about that a lot in regards to Southern Reach since I knew that it already was going to have to be something that was ambiguous, it was already going to have to leave that room for the reader. And I was rewarded with amazing acts of creativity: a lot of fan art, a lot of music, fan fiction—there’s fan fiction of True Detective mashed together with Annihilation that’s actually quite wonderful and startling and fixes problems in both things. And so I actually make that part of the deal. We made a limited edition chapbook of fan art and other illustrations and maps, to coincide with the release of the hardcover of The Southern Reach Trilogy because it was all just so amazing. With Borne there was fan art before the book even came out, because there were excerpts and there was a giant bear and everything else. I love that. I love the way that, because I’m highly visual, those images then feed into something else for me. And then also, the thing you were talking about with regard to parenting, creating, and everything else—those two things sometimes combine. One reason this book gestated for so long—even though most of my books gestate for a long period of time—is, you know, I was a step-dad, and I needed to think about what that experience had been like. So like the long mouse reference is something that my daughter Erin said when she was a child, walking around she saw a ferret, pointed, and said “long mouse.” She said a lot of things like that. There’s another thing she said involving bears which was quite hilarious. I was pretty terrible when she would ask me for information about something and I would make something up. And she got wise to this really fast, and so she started turning the tables. One day, I was entering a Jewish household—I was agnostic and I really wanted to learn more about Judaism—we were walking along and there was this bear next to the synagogue, she pointed to it and said, “That’s the Hanukkah Bear!” And she proceeded to go on for like twenty, thirty minutes about the Hanukkah Bear, its religious significance, the constellation in the sky that mapped to it, everything else. And I was so excited about this that the next time I was in a synagogue I went to the rabbi and I was like, “How about that Hanukkah Bear?” Repeating all this information, while Erin was just laughing. And she was like eight. And oddly enough that came back very directly in Borne, because there’s a scene on a rooftop with Mord flying against the night sky, and without that Hanukkah Bear constellation I don’t think I would have thought of that scene in that particular way. So, yeah, sometimes parenthood and creativity are very much combined.

JJ: It seems like you have such a terrific relationship with fans creating art based on your work, both musicians and visual work. Can you trace how visual work or music has influenced your work?

JV: Yeah, there’s a great artist named Scott Eagle that Ann, my wife, first discovered for one of her magazines, and then he did book covers for some of our books, and he has an amazing process. It’s very organic, and then very rigorously mechanical later, and that’s similar to how I work. And so there’s a creature called “the strange bird” in Borne, and I was thinking about his incredibly representations of birds. He had this amazing bird where, if you look at the cross-hatching on its wings—and it actually looks like it’s part of a plant—there are whole cities burning. You can see all this detail. He just does these amazing things, because, back in the day when he was first starting out, he started copying all these old masters so he could learn their technique and now he can just do it by hand. And so I got that idea from “strange bird” and also from his philosophy, and wrote a novella, after Borne, based on his reading of Borne and his notes to me about Borne. It often happens like that, that there’s a give and take. Really, the strange bird novella that will probably come out in the summer from MCD, is the direct result of our communicating and back-and-forth, and he actually did art based on Annihilation too, which is pretty amazing.

JJ: The Strange Bird is what that’s called?

JV: Yes.

JJ: And the bestiary that we’re talking about, when can we look forward to that?

JV: I don’t know. The bestiary’s a lot of fun. Like, there’s a duck with a broken wing in Borne, just a tiny little scene that was inspired by a duck I encountered while birding once, and I was just struck by the fact that mallards mate for life, so the mate was just going to stick with the other bird even though it had a broken wing, no matter what happened. So I airlifted the duck to resurrect it into the story, and then that got me to thinking about the bestiary. Now the broken-wing duck actually has a lot of backstory. It may not actually even be a duck. It could be a trap. So the bestiary, I don’t know when it’s going to come out exactly. I think they’re still creating illustrations for it, so.

JJ: What else do we have to look forward to? What are you working on now?

JV: Well, I’m heavily into something called Hummingbird Salamander, which is about a woman in the tech industry in her late forties who doesn’t have very much environmental awareness, and one day is given a key to a locker that contains a taxidermied hummingbird and a taxidermied salamander, and when she investigates it turns out they’re among the rarest species on Earth. When she finds out who gave her the key and why, she goes into this descent of wildlife tracking, eco-terrorism, and everything else. That book is pretty much set in the present day. And Tor.com is publishing, in September, a long, long story of mine called “This World is Full of Monsters,” which is set in a kind of alternative universe to The Southern Reach stuff, like, what would have happened after Acceptance in another universe?

Jeff VanderMeer is an award-winning novelist and editor, and the author most recently of the New York Times bestselling Southern Reach Trilogy. His fiction has been translated into twenty languages and has appeared in the Library of America’s American Fantastic Tales and multiple year’s-best anthologies. He grew up in the Fiji Islands and now lives in Tallahassee, Florida, with his wife.

Jac Jemc is the author of My Only Wife, a finalist for the 2013 PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction and winner of the Paula Anderson Book Award, and A Different Bed Every Time. She teaches writing in Chicago and edits nonfiction for Hobart.