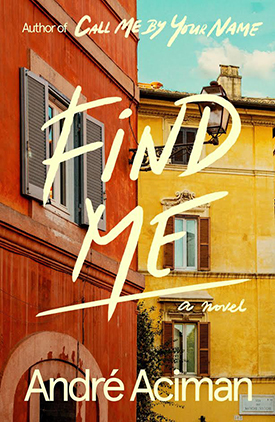

No novel in recent memory has spoken more movingly to contemporary readers about the nature of love than André Aciman’s Call Me by Your Name. First published in 2007, the book recently became an Academy Award–winning film starring Timothée Chalamet as the young Elio and Armie Hammer as Oliver, the graduate student with whom he falls in love. Find Me, an instant New York Times bestseller, brings us back inside the magic circle of one of our greatest contemporary romances to ask if, in fact, true love ever dies. André Aciman joined BuzzFeed‘s Tomi Obaro to discuss Find Me, and they cover everything from how the movie influenced Aciman’s writing, to why Oliver’s perspective is hardest for him to write, to the infamous peach scene.

Warning: This discussion contains spoilers!

Obaro: I’m curious to know how you’re feeling about the publication of Find Me. We were talking backstage about how there is so much more pressure now with the success of the film adaptation of Call Me by Your Name. So, how are you feeling?

Aciman: I’m feeling healthy! But basically, there are so many expectations and everyone is already coming to the book hoping that they will see more of this and not enough of that, that I feel very boxed in. I’m telling people, be patient, you will be rewarded. At least I hope you will be. Just be patient.

Obaro: Maybe I did it the wrong way but I saw the movie, then went back and read the book in one sitting, one weekend. I’m curious to know how you decided to come back to the book and why, when in previous interviews you said you were hesitant to revisit Elio and Oliver.

Aciman: I’m always hesitant about everything. That’s me! I’m insecure, I’m diffident, I’m scared, I’m timid, all those things—things that Elio happens to be too. I started writing something about Elio quite a bit after publishing Call Me by Your Name, because it was a fun book to write. It really was enjoyable and there were certain scenes that I wanted to go back to and revive. And when I started writing, I wrote in the voice of Elio. I wanted him to be a bit older, and also maybe having an affair, but still thinking of Oliver, and so on. Then I decided I was going to write about Elio and see what happens to him in college, and after college. And every time I started, it just fell flat, because I was just doing Call Me by Your Name again, and one should never do that. I felt that every single time I tried, by page one it was something derivative, not false, but derivative.

Until three and a half years ago, I was on a train when a person who was very pretty and had a dog with her sat next to me. She said, can you please hold the dog while I go to the bathroom, and we started talking. I said, this is a wonderful situation. But she got off two stations afterwards and I decided I’d write something about it. I had no idea what I was doing. After about three or four pages, I realized, I had a character for this. I’d manufactured him almost ten years prior. I thought, let me bring him back. That’s how I started the sequel. I said Elio has to appear, but I’m going to wait for him to appear. His father is going to meet him and they’re going to have a nice time together and go back to places they remember and so on. And that is where Elio comes in, about one hundred pages into the book. If you have no patience, please slog through it! [laughter] I find the father to be fascinating and I find this character with the dog he meets on the train, Miranda, to be an amazing character.

Obaro: Talk a little bit, then, about why you decided to focus on the father as opposed to creating another character, or centering Elio and Oliver?

Aciman: I couldn’t think of another one and I liked what I’d started writing. I love the father in the train speaking to this woman with the dog who is bringing a birthday cake to her own father, who is dying. It felt very natural for me to just take that character and see how it developed. And it developed, in my view, quite easily. And I was having fun. One of the things that you don’t want to do as a writer is write something that feels boring. You want to create scenes that are like the peach scene: it’s fun, it’s crazy. I’m probably sick in the head for writing it. But you write it and you enjoy it and you see where it goes. I love not knowing where I’m going. I never know what I’m going to say, I never know what I’m going to write next. I go plotless, since I hate plot anyway.

I love not knowing where I’m going. I never know what I’m going to say, I never know what I’m going to write next.

Obaro: At what point in the process of writing those initial scenes did you realize this was an actual book?

Aciman: Oh, you never know that. If you’re like me, maybe you hit page forty and think, eventually it’s going to die and I’ll have to throw it away. You just think that—negative until the very end. And then at the very end you say, okay this is where the story or chapter ends. That means the first one is over with. I never know, and I don’t like knowing. I only know when I’m at the very end of a story. Then I know there’s a few more steps and we’re done. But for 97 percent of it I have no idea where I’m going.

Obaro: What is the timeline of working on this sequel in relation to the movie?

Aciman: The only thing I took away from the film was that I called the father Samuel in Find Me. I didn’t ever give him a name [in Call Me By Your Name] because I seldom name my characters. He was Professor P; that was all we knew. The movie gave me Samuel. But I didn’t imagine my characters as the people I had seen in the film.

Obaro: So it did feel like they were separate?

Aciman: Yes, they’re totally separate. The voices are totally different. This is not the voice of director Luca Guadagnino. It is a totally different voice. But still, I started writing Find Me before the film came out when the movie was being edited. I had been on the set for two and a half days and that was it. There really was no connection between me and the film.

Obaro: And how long did it take you to write Find Me?

Aciman: I think about a year. But that’s because I’m a very slow writer.

Obaro: That doesn’t seem that slow to me! What were some of your inspirations for the book and what is your process in general? Did you travel, listen to music? Are there certain rituals that you have to do while you’re writing?

Aciman: I don’t have rituals. Basically, I call it “stealing time.” Because if I’m not doing anything, if I’m not teaching, then I’ll write. That’s all I do when I’m not doing anything. I don’t watch television, I don’t go to the movies. I’d like to think that I go to concerts. I don’t. I love concerts but I just don’t. It’s a question of patience. If I go to the opera, I walk out halfway through it! Even if I love it. So there’s probably something wrong with me. I don’t do much except write. I wake up and go to the gym. I’ll come back and buy a coffee and I’ll start working. Usually I go back to whatever I was writing the night before and I hate it and tear it apart, and we start the day that way! Most people don’t love themselves, and you say, did I write this? Yes, you did.

Obaro: Setting is such a huge part of this book—it spans across the world from New England to Italy. Do you just rely on memory or past trips you’ve taken? Do you feel like, I have to go to Italy to write this?

Aciman: No, I’m not like that as a writer. I don’t even have a speck of the reporter in me. I just remember, and if I cannot remember, I make up. I think Paris at night, if you walk on the cobblestones at night after a rain, and if you’re walking with somebody you happen to like or love, it’s a wonderful Paris. And suddenly you don’t have to describe Paris. All you have to say is the cobblestones are sleek, cold, but not freezing . . . and you’ve got your Paris. I seldom describe places, even Italy. When I describe Rome it’s only transitory, episodic. I used to be a travel writer and would have to describe the feeling of the place and would not have written anything because I rely on memory. And then I would submit the piece and the editors would say, what we need is a box. You know that box you had in old travel magazines where you state what restaurants to eat in, what hotels to go to, what to see, what to do, et cetera. I didn’t know what to put in the box. So they had to have somebody else put facts in the box for me because I don’t see things that way, I don’t note anything. I don’t even remember much. But I keep with me the feeling of the place.

Obaro: I’m going to read a tiny portion that I thought was interesting. This is Oliver speaking (spoiler alert: Oliver is back!).

Aciman: One hundred fifty pages later!

Obaro: It’s pretty far in, but worth the wait. Oliver says: I’ve had to sever many ties and burn bridges I know I’ll pay dearly for, but I don’t want to look back. I’ve had Micol, you’ve had Michel, just as I’ve loved a young Elio and you a younger me. They’ve made us who we are. Let’s not pretend they never existed, but I don’t want to look back.

In the book, a lot of characters are talking about relationships that have ended, or that they have mourned. Is Oliver’s sentiment on love one that you share?

Aciman: No. First of all because I don’t think I understand Oliver. He’s so foreign to me. But he is saying something here that I think is important to the book. He is saying, whatever happened in the past belongs to the past. I don’t want to dwell on the past when we have a future. There is something to come that I’m more interested in. And that is typical Oliver. He’s now forty-four years old. He’s a bit insecure and certainly has more depth to him than he did in the first book when he walked into the café and started playing cards with everybody and everybody knew him. This is a more tentative character. However, he doesn’t want to do what everybody else does in this book. They all perform this act of what I call vigils, which are visits to particular corners that are dear to them in a particular city that they want to touch base with so they can reconnect with the person they used to be many, many years ago.

Obaro: Say more about Oliver. In Call Me by Your Name it’s narrated totally by Elio, first person. Oliver appears for the first time in the first person in Find Me, but his voice is not so prevalent in the book. I’m curious why he’s a challenge for you to figure out.

Aciman: He’s a challenge because he’s still a very confident person and I cannot relate to that at all. I don’t get how people are confident—I wish I were. I’m always attracted to people who are super confident and not insecure. I’m exactly the opposite. I like people who make decisions for me because I can never decide anything: should I have coffee or tea? What do you think? It doesn’t bode well. I always feel that the other person makes up their mind for me, and for themselves. I’ve always admired that. And that’s Oliver for me. Which is why Elio admires him so much—Oliver is a force of nature that he’s totally unfamiliar with. I am interested in Oliver but I can’t penetrate his mind. When I write him in the first person, it is a challenge because when you’re writing the first person you are always aware of what is not connecting between you and others, between you and life, between what you want and what is given to you—that’s what the first person is always about. It’s never a confident first person. Writing the first person from Oliver’s perspective, all I had to do was have him say, gee, I used to be attractive to people, what happened? How come they all got partners and they aren’t interested in me? He doesn’t understand that; that’s unfamiliar territory.

People write to me all the time and ask me, could you write Call Me by Your Name but this time from Oliver’s perspective? It would be a very short story! At that age, he has almost no insight into himself. Though, at one point, Elio says to him, “Oh, are we not going to speak to each other now that I’ve spoken to you. Are we going to pretend that we don’t know each other?” And Oliver’s response to him is, “Oh you’ve been doing quite a bit of that.” So, Oliver is aware of what Elio is doing, even when Elio thinks he is very clever. Oliver has insight but not continuously.

Obaro: Do you think Elio and Oliver are soulmates? Do you believe in soulmates?

I’m in love with their love—how could you not be?

Aciman: I think they have to be because I wouldn’t spend so much time on them otherwise. I’m in love with their love—how could you not be? You watch these two characters who are so unbelievably open with each other. The whole book is about characters who are extremely open with each other—I’ll shut my eyes and you can do what you want, or, you can tell me whatever happened to you in the past, please do. This kind of openness is not exactly a common thing between people, especially people who have been together a long time.

Obaro: You mentioned the peach scene before, which is my very awkward segue into sex! We’re going to go there. Your books are very erotic, but also very tasteful. What do you think are the secrets of writing good sex scenes, scenes that are erotic without being pornographic?

Aciman: What I don’t want to do is write sex frontally. Some of the scenes that are very graphic are graphic because they are recollected, they are not exactly described in the moment. The first night that Elio and Oliver sleep together, there is a moment in which it becomes clear that they have smoked some pot together, and that Elio is no longer aware of how much time has gone by, and he doesn’t know if they have already discussed something or not. That’s exactly the kind of opaqueness that you want to throw on a scene, and you don’t want to be direct. Then of course you find out two pages later that there was something that Oliver did to Elio that was not described when I was describing their alleged sex together, so it was more graphic in recollection. You never go frontally, you always come about it obliquely. I think that works for me. For instance, some thought that dwells in the mind of the person who is having sex that distracts them, but only retrospectively. When Elio and Oliver were making love for the first night, there is a book on the bed. And Elio does not realize that there was a book, I guess he’s not aware of the book, but the book is there on the bed. And he realizes later that he even looked at the title of the book! He wasn’t aware of that in the moment. And that’s exactly how I like to approach writing sex. For those of you who have read Ovid: you have very graphic scenes, and they’re never graphic enough.

Obaro: Classical music is another recurring theme in both books, and in Find Me Elio is a professional pianist, and the sections of Find Me are named after classical music terms. It’d be nice to know why that comes up in your works. There’s even a plot point of a mysterious hidden score. Did you foster dreams of being a pianist?

Aciman: I always wanted to be a pianist, that was my dream, but I cannot play a single note on the piano. I cannot even read music. My familiarity with music is entirely passive. I only listen to music. But I am very attached to music. Whenever I mention a classical piece, I am not trying to say that this is the soundtrack of the scene. Rather, the moment people speak about classical music in my writing, what they are really doing is invoking a higher aesthetic sensibility. It is something really amazing and almost like a religious experience. It is like invoking some kind of divinity when you mention classical music. I can’t articulate that enough because I don’t know how to. But for me to mention Bach or a piece by Beethoven—and there’s a lot of Beethoven in the book—it means we’re not dealing with everyday facts, we’re not dealing with the description of the city as you know it, I’m not reporting to you day-to-day incidents, I’m in a different dimension. We’re dealing with classical music which means our feet are not on the ground, we’re hovering. That’s why I bring in classical music. Some people have told me, enough with the classical music, we get it, you’re showing off. But I’m not showing off! I can’t play this stuff! I wish I could.

Obaro: I was so impressed you know so much about music. It’s all for show?

Aciman: It’s not for show, but it’s not because I play it. It’s because I love it and admire people who can do it. I envy people who can do it.

Obaro: Do you want to read from the book?

Aciman: I’ll read a short passage. In Find Me, there’s a thing called vigils. In places in Italy and Spain and Portugal, as you walk into little old streets, you will see at the corner a little shrine. Usually there’s a lamp lit. What you do at the shrine is you just stare at them, or do the sign of the cross, or you pray, and then you leave. That’s where the idea comes from for vigils. What happens in this passage is Elio and his father perform something called a vigil, much like people often go back to a university where they were a student, hoping to reconnect with something, with the person that they used to be, hoping that person is still there. I’m exaggerating, but why are you going back to see the building where you lived as a student? You’ve no real interest in it. Especially if you go with someone else—they’re like, yeah, nice building. But you say, I want to share this with you! And they’re like, nothing to share, I’m sorry, it’s nice but can we go now? Here is a moment in which Elio and his dad and Miranda, who is the person the father meets on the train, are walking in Rome and they have just had coffee, and Elio says, I’m going to take you to a place, it’s a place that many readers will likely recognize. His dad says:

When we reached Via della Pace I thought he was about to take us to one of my favorite churches in the area. Instead, no sooner had we sighted the church than he made a right turn and took us to Via Santa Maria dell’Anima. Then, after a few steps, and just as I’d done with Miranda the day before, he stopped at a corner where a very old lamp was built into a wall. “I never told you this, Dad, but I was drunk out of my mind one night, I had just vomited by the statue of the Pasquino and couldn’t have been more dazed in my life yet here as I leaned against this very wall, I knew, drunk as I was, that this, with Oliver holding me, was my life, that everything that had come beforehand with others was not even a rough sketch or the shadow of a draft of what was happening to me. And now ten years later, when I look at this wall under this old streetlamp, I am back with him and I swear to you, nothing has changed. In thirty, forty, fifty years I will feel no differently. I have met many women and more men in my life, but what is watermarked on this very wall overshadows everyone I’ve known. When I come to be here, I can be alone or with people, with you for instance, but I am always with him. If I stood for an hour staring at this wall, I’d be with him for an hour. If I spoke to this wall, it would speak back.”

Time has occurred. Time happens to people, it happens to all of us.

This is the vigil, this is the spirit of the book. It’s a totally different book from the one that everybody expects to find. Time has occurred. Time happens to people, it happens to all of us. And it’s not a pleasant thought when we think about time, because when we think of time what we’re really saying is we’re getting close to this other thing called death. We don’t like death. I don’t accept death, I think it’s a big mistake. People tell me, “But it is part of life.” No. I say it’s a big, huge blunder! People say, “Well, do you want to get old for infinity, nine hundred years old?” No, in my version you’d stop getting old, that’s the point, and they say, “What about overpopulation?” and I say stop being practical! But anyway, time is so important in this book because these are all people reflecting on the passage of time. And of course Elio and Oliver have many years between them, a lot of time, and sometimes reconnecting with someone after many years can be a disaster—and people think, we should never have gone back to it. I’ve gone back to my birthplace and my feeling was, I should never have gone back, I should have stayed with my memories. Those were good enough. Many people tell you, don’t ever go back, but we are drawn to the past. And many of us can’t get over the past.

André Aciman is the author of Eight White Nights, Call Me by Your Name, Out of Egypt, False Papers, Alibis, Harvard Square, and Enigma Variations, and is the editor of The Proust Project (all published by FSG). He teaches comparative literature at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. He lives with his wife in Manhattan.

Tomi Obaro is a senior culture editor at BuzzFeed News and is based in New York.