In Williamsburg, Brooklyn, just a block or two up from the East River on Division Avenue, Surie Eckstein is soon to be a great-grandmother. Her ten children range in age from thirteen to thirty-nine. Her in-laws, postwar immigrants from Romania, live on the first floor of their house. Her daughter Tzila Ruchel lives on the second. She and Yidel, a scribe in such demand that he makes only a few Torah scrolls a year, live on the third. Wed when Surie was sixteen, they have a happy marriage and a full life, and, at the ages of fifty-seven and sixty-two, they are looking forward to some quiet time together. But then Surie finds out she is pregnant. At her age, at this stage, it is an aberration, a shift in the proper order of things, and a public display of private life. She feels exposed, ashamed. She is unable to share the news, even with her husband. And so for the first time in her life, she has a secret—a secret that slowly separates her from the community.

Here, author Goldie Goldbloom discusses On Division with Cheryl Sucher, author of The Rescue of Memory.

Cheryl Sucher: I was just talking to Goldie about how I’m also Jewish and the child of survivors and when I moved to New Zealand, I belonged to a Jewish congregation in Dunedin, the southernmost Jewish community in the world. I spent five years researching the history of the Jewish population in New Zealand. Today I found out something I didn’t know about Goldie’s family—that they came from the North West of Australia. The first Jews that came to Australia and New Zealand from Germany following the gold rush, as did the first Jews that came to the United States. That’s an interesting common background we have.

Just to introduce myself before we get started: I am a writer. I wrote a novel called The Rescue of Memory, which was published so long ago I can’t remember what year. Since then, I’ve been a journalist and a fiction writer. When I was in New Zealand, I did a lot of book-reviewing and feature writing. I was also the host of a local talk show called “Chat Room.” When I came back to New York, I said, “Let me segue my worlds so I feel less schizophrenic,” and so I started this series about two years ago and it seems to be going very well. I’m very happy to talk to Goldie, who has written On Division, which I think is truly an extraordinary, unique book. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever read.

The novel begins with Surie, who is fifty-seven years old. She has had eleven pregnancies and eight births. When she discovers, to her incredulity, that she is pregnant with twins, she becomes worried about how her community is going to receive her, what she is going to do. There are a lot of secrets that she’s withholding and that come to fruition with the pregnancy. She is married to Yidel, who is a Torah scribe. She loves him. They were married at sixteen. She was pregnant at sixteen and pregnant at fifty-seven. The book traverses their relationship and is an insight into her world. You see her world through her eyes; a very unique characteristic of the novel.

There are so many places to start, but I always like starting with the title. This title has a lot of meanings. Tell me how you came to it.

Goldie Goldbloom: It’s my great luck in getting a really good editor! I’m terrible at titling my books and I typically just give them titles that are functional. The original title of this novel was “In Williamsburg” because it’s set in Williamsburg. But my editor Jenna Johnson came up with something far more indicative of the contents of the novel.

Sucher: The novel came out of a story that you wrote. Tell me about that story and how it became the novel.

Goldbloom: Many years ago, I wanted to write something that somebody would be horrified by but simultaneously laugh at. Eventually, the story I wrote became part of my story collection in Australia. It was published in a very different form there. More recently, I said to myself that I was not done with the idea.

I wanted to write something that somebody would be horrified by but simultaneously laugh at.

About two years ago, one of my sons said: “I have all of this good music but I can’t bring myself to record it.” I said: “Come on, don’t be a jackass! You should record your music.” But nothing that I did would light a fire under this kid until I thought maybe I could challenge him in some way. I told him, “I want to have a creative challenge with you. We’ll lock ourselves up in our rooms for ten days and I will write something. And you will record your music.” He said, “You’re willing to do that?” So I put everything on hold for ten days and I wrote this book.

Sucher: You wrote the entire book in ten days?

Goldbloom: Yes.

Sucher: Was the original story the Surie story? Was that the basis of the novel?

Goldbloom: Yes. During those ten days, I was feeling kind of competitive. I was thinking to myself: “Well, if he’s going to record all of this stuff that he’s already made, I need to do something that’s halfway decent.” It couldn’t be something that needed research because I only had ten days. It had to be something that I knew really well. The Hassidic community, hello? I know that really well. I already had the idea of this story. I had already written the basics. With that germ of an idea, I could fly. And once I started, I loved it. It was fun.

Sucher: There was a little bit of magical realism, I felt, throughout the novel. In the sense that the more pregnant Surie gets, the more visions and imagination she has. Also, the whole idea of a fifty-seven-year-old woman being pregnant with twins, after having breast cancer and a double mastectomy—was that imagined or was it based on something that you knew?

Goldbloom: It could be that I know somebody who had a child at fifty-seven. That’s not the part that’s magical realism.

Sucher: But it is pretty extraordinary.

Goldbloom: I think it happens fairly often; they just don’t report it because most people who are fifty-seven and have a surprise child would not want to be in the newspapers.

Sucher: One of the things I tell people about this book is that after reading it, you really feel like you’ve given birth. The reader really lives with Surie through every aspect of her pregnancy. So, I was wondering, as a Hassidic woman, have you always read secular material, or what was your path towards writing?

Goldbloom: I was a really nerdy little kid. I didn’t fit in with my classes. I skipped two grades so I was much younger than everybody. At recess, the kids would go around bullying and doing all the lovely things that happened in schools in the ’60s and ’70s. I thought I’d protect myself from that by going to the library. There was a big library at my school. I used to go and work in there at lunchtime. I was really obsessed with being in the library. At some point, I said to myself that by the time I graduated from elementary school, I would have read from A to Z in the fiction section of the library. Which I did. I started reading and counting them all off. I’m a very big reader and I think that’s true of almost all the writers that I know. You have to be a good reader to be a good writer.

Sucher: I think that a lot of people who want to write, don’t read. And you can recognize it.

Was your community and your family accepting of this book? The women in Williamsburg don’t have access to the internet; their whole life is devoted to being a mother, to being married, and to their community. It seemed to me that you took a step out, just like Surie does in the novel.

Goldbloom: Despite the fact that people insist what I am about to say didn’t happen, it totally did. When I was in seminary in the Lubavitch community in Crown Heights, we were told that we could not go to the library. We were told that if we went to the library, it would seriously affect our chance of marriage. There was an atmosphere that wanted to make us feel like we were going to lose something if we went into a library. At the same time, I worked at the library! It was my job. I wanted to be a really good girl and I didn’t want to announce that I was working at the library, at this place where we were forbidden to go. Of course, there are exceptions to every rule. Certainly now, but even thirty years ago, there were a very few people on the edges of the community who went to the library. Nowadays, the public library in Williamsburg is in the main section of the community. If you stand and watch on that block, you will see that nobody will even walk on the side of the street where the library is built.

Sucher: That’s amazing. So your obsessive reading, was that something you kept secret? Did your family know about it?

Goldbloom: Well, growing up, yes, because my family is not religious. They told me to read more. They joked, saying, “Maybe it will fix you.” But as far as the community went, I was a secret reader.

Sucher: Did you marry into the Hassidic community?

Goldbloom: I was Hassidic long before that but I married someone who also is part of that community.

Sucher: Did you go to seminary in Australia, where you were raised?

Goldbloom: I was born and raised in Australia; I went to seminary in Australia.

Sucher: I was doing some research and I saw that there is a school for Hassidic women filmmakers now.

Goldbloom: That’s really cool. I mean, the world has really changed a lot since I was in seminary. When I walk in Crown Heights or in Williamsburg these days, I can see that things have changed. They move really slowly, but they can change. Things in Williamsburg change very slowly, things in Lubavitch change faster, but still really slowly in comparison with the outside world.

Sucher: How did your ambition as a writer jibe with your life as a Hassidic mother?

The thing is that I never wanted to be a writer. I really wanted to be a pathologist or a coroner but I knew that would not happen.

Goldbloom: The thing is that I never wanted to be a writer. I really wanted to be a pathologist or a coroner but I knew that would not happen. I had to forget it as an orthodox person. It was completely off the table, a giant no-no. I thought that, since those professions could not happen, I would be a neurologist. I studied neurology and I was interested in becoming a neurologist. While I was studying that stuff, I was still writing stories. When I wrote my first book, The Paperbark Shoe, I thought nothing would happen with it; that it was just going to stay in a drawer. By the time I finished it, I was thinking of divorcing my ex-husband and needed to figure out an income, because I didn’t have a full-time job. I made a list that included things like “lawn-mowing service.” My options were poor, extremely poor. I never thought that I would be teaching creative writing at two world-class universities. That was not on the agenda at all. Instead, what happened was that I was camping in Wisconsin and I got a phone call saying that I had won the AWP Award. I asked whether that was good and what it was. I didn’t have any clue; I had no connection to that stuff. I asked “how did I win it?” They said: “That book that you wrote.” I told them that nobody had that book because I hadn’t submitted it for the prize.

Sucher: Your publisher had submitted it for you?

Goldbloom: Everyone who knows me knows that I have terrible computer skills. At the time, I was in a little writing group and didn’t realize that one of the people in the writing group was the editor of Story Quarterly. She told me that she loved the stuff that I was doing and asked me to give her a chapter of it for Story Quarterly. I went home and I realized I didn’t know how to copy and paste. I didn’t know how to do anything. I’m a terrible typist and I had just gotten my first computer. I called her and told her that I didn’t know how to chop a part out, I can’t send you just a part of it. She said it was all right and told me to send the whole thing. Fast-forward, Goldie completely spaces out on that, forgets that she sent the whole thing. And the editor of Story Quarterly forgot to tell me that she submitted it.

Sucher: Those ten days to write On Division must have been nonstop typing.

Goldbloom: I actually write longhand. I write significantly faster longhand than I do typing. My son types so fast that you don’t even see his fingers. It’s faster than I think!

Sucher: Toni Morrison said that when she sat down to write she wanted to write about things that she had not read, about her world and her life. I totally feel that way about On Division. You’re really giving us a female insight. All the reports that have been made about living in a Hassidic community have been either reportage from people outside the community, or from men, or they’re things that are completely censored. Your book really is a revelation about what it’s like to be in this community and what it’s like to love the community. Usually the stories about the community are about leaving.

Goldbloom: Typically, or at least the books that I’ve read—and I feel like I’ve read everything about the topic—either claim that Hassidic people are saints and completely unapproachable, or devils and completely unapproachable. Or they’re written by people who have left the Hassidic community and no longer want to have any part in it; or people who like the Hassidic community, know nothing about it, but still want to write something about it. I didn’t want to do that. To me, that’s baloney. I wanted to write something that was accurate. My fact-checkers worked really hard to make sure it was accurate and they were excited about it.

Sucher: What do you mean by accurate? Accurate in terms of the religious law?

Goldbloom: Just every part of it. Do you turn left or right on Division Avenue? Every single thing. I wanted it to be accurate and balanced. I told them that I wanted them to go through the novel with a fine-tooth comb; I wanted them to find anything that is inaccurate. I wanted them to help me make sure that the novel was exactly right. Not just the emotions, which I think I can get, nor just the Jewish law, which I know, but the specifics of living in Williamsburg, I know it well, but I haven’t lived there. I wanted that to be exactly right.

Sucher: Another thing I really liked about the book is that people think it’s all devotion, all seriousness. But there’s a lot of humor and there’s a lot of love. The relationship between Surie and Yidel is filled with humor. There is a lot of humor in the household. There are a lot of children running around, and food, and a lot of eating food when the characters are not supposed to eat. There is a dimensionality to the experience which I think is very wonderful.

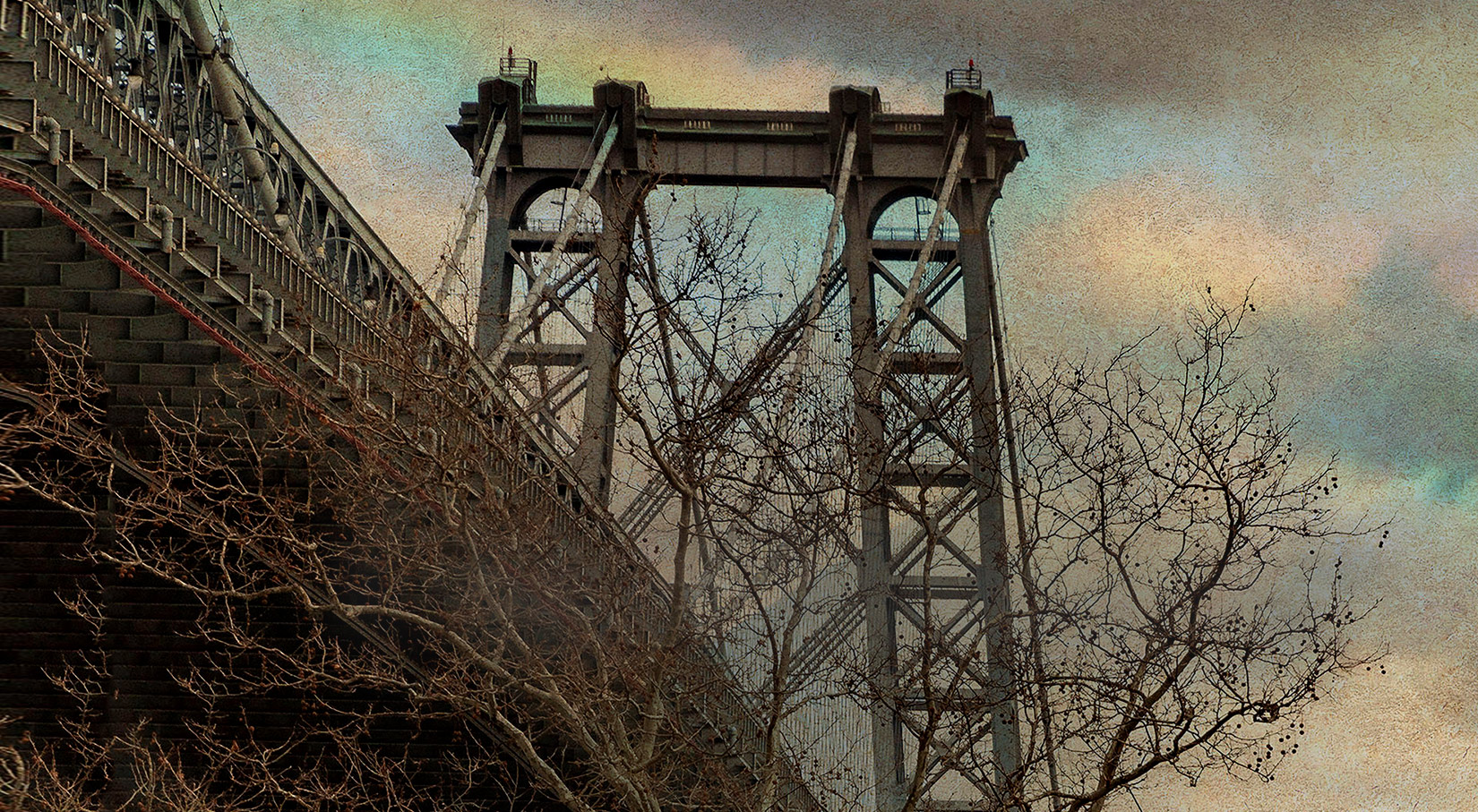

Goldbloom: Farrar, Straus and Giroux put a bridge on the cover of the book. That is exactly what I wanted to achieve with this book. I wanted to accomplish this idea that you can create bridges between really different people. You can create bridges between Jews and non-Jews, between the most Hassidic people in the world and their children who might be gay. You can create bridges between people who are right-wing and people who are left-wing. What does it take to create those bridges? To me, that is the real story of this book. It’s about showing how you set aside some things in order to find what is really essential. I hope I achieved that. I feel like I did. In the moment when I finished writing it, I felt like I did what I had wanted to do.

Sucher: Did your son read it?

Goldbloom: Yes, he did. The book is dedicated to him.

Sucher: How has the reception of your work been within and without of the Hassidic community?

Goldbloom: I’ve been really happy. There are quite a few people who have read it in Williamsburg and loved it. There are a lot of people in Crown Heights and other Hassidic communities who have read it and loved it. I heard from women who said that I got them. “You wrote our lives accurately without too much this way or too much that way.” I wrote the way it is.

This has nothing to do with that, but I like to tell this story. I’m completely changing the subject. But not really. I happen to have a pen pal who is an older, Amish woman. She has eighteen kids. She likes to drive down to visit us in Chicago. People think of Amish people in similar ways that they think about Hassidic people: unapproachable, remote, very religious, pious people. When the family comes down to Chicago, the first thing that the father does is take a bath. He is a tiny man and I have this enormous bath. For them, they roll out a fiberglass bathtub on wheels and it takes them four hours to heat up enough water to take a bath. My bathtub fills up in about five minutes and it’s enormous! So, the first thing that the father does when he comes to my house is ask whether he can go upstairs and take a bath. He zooms upstairs, turns on the taps, gets inside the bathtub with all the bubbles and you can hear him laughing from outside of the bathroom. He’s sliding down into the tub and you can hear the water splashing around! It’s completely amazing! This is not the way people think about Amish people, right? It’s also not the kind of story we tell ourselves about the “other”—whoever we think of as “not ourselves,” whether that is religious people or poor people or people of color or Republicans. This kind of story helps make somebody you think of as being so far away, just like us. Everybody is just like us. It’s that essential humanity.

Sucher: One of the very moving parts of the book is Surie’s relationship with her beloved son who is wrestling with being gay. In your own life, it seems like you’ve been very committed to acceptance and activism. How important is that for you, in terms of what this novel has accomplished and your own life in terms of building bridges?

Goldbloom: It’s hugely important. A while ago I started a blog called Frum Gay Girl which was interviews with a lot of different people who weren’t out in the Hassidic community. The reason that I started the blog was because therapists or family members would call me and say, “Could you talk to this person? Could you assist this gay Hassidic person?” And each time I would say, “It would be really great if you could meet some of the other people.” And each time they would say, “No, no, no, don’t do that. That’s way too scary. Don’t introduce me to anyone, don’t tell anyone my name. I need to stay secret.” And I thought, gosh, there’s a lot of people, and if I could only connect them, if they could only meet one another, they would feel less scared, less alone. And so I started writing this blog. I was like: Okay, I’ll interview them anonymously and I’ll post the interviews. It’s sort of a vicarious meeting with other people that are like you. So, I put the blog up, and I put an email address up, and I got thousands—I want to say thousands—of responses. I still get calls from people who will say stuff to me like, “Oh my god. You saved my life. I thought I was the only person.” And not just Jewish people. There were people who were writing from Mormon communities, and Muslim communities, and other communities of faith, other right wing communities to talk to me about being queer in a religious space. And I just thought: Wow, that’s rough. And as a result of that and Eshel, an organization that does really good work, I’d also, unfortunately, hear over and over again about the deaths of young people in the community. It’s so difficult to have to choose between everything you know and love, and who you are as a person. It’s terrible. What kind of a choice is that? That’s a killing choice. In fact, I gave this book to a young man, a young man from a Williamsburg family. He read it and came to my house on Friday night and he fell on the ground sobbing. And he said, “You wrote this for us. You wrote this for us.” And it’s true, I did. If the “us” is anyone who has ever felt excluded.

It’s so difficult to have to choose between everything you know and love, and who you are as a person.

Sucher: You also talk about abuse. There’s been abuse within the Hassidic community. You talk about opening your arms, and about exposing some of the things that are kept secret. A lot of the books about this community, to me, seem to be about dealing with the pain of secrets, of holding secrets.

Goldbloom: That’s one hundred percent true. If you can’t talk about something, it just gets bigger and more difficult to talk about. Secrets eventually distort the people who are holding them.

Sucher: What does your family think of your work? Do they read it?

Goldbloom: No way. Are you kidding me? My family doesn’t read my work. The Chicago Tribune came to interview me in Chicago about my first book and my son, unbelievably—this was the same kid doing the creative project with me—anyway, he’s sitting on the stairs and the woman from the Chicago Tribune, she finishes talking to me and sort of turns to him and says, “So, do you want to be a writer like your Mom when you grow up?” And he goes, “Hell no. No way! Do you know how hard that is and how little you get paid?” Most of my kids are just like, “Yeah, no, I don’t want to read that.”

Sucher: But you have been able to support yourself. You’ve made a life for yourself, haven’t you? Yes? I think so. It’s a struggle? No comment?

Goldbloom: Well, my only comment is health insurance, please!

Goldie Goldbloom’s first novel, The Paperbark Shoe, won the AWP Prize and is an NEA Big Reads selection. She was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, and has been the recipient of multiple grants and awards, including fellowships from Warren Wilson, Northwestern University, the Brown Foundation, the City of Chicago and the Elizabeth George Foundation. She is chassidic and the mother of eight children.

Cheryl Sucher is an award-winning journalist, essayist, reviewer and fiction writer who lives between Cranbury, New Jersey and the Hawkes Bay, New Zealand. Ka Hua E Wha: The Southernmost Jewish Community in the World, her contribution to Jewish Lives in New Zealand was published in 2012 by Random House NZ and she has been a frequent contributing book reviewer and feature writer for The NZ Sunday Star-Times and The NZ Listener. Her first novel, The Rescue of Memory, was published by Scribner and an excerpt from her second novel in progress, Lost Cities, was published in 2013 in Printer’s Row, the Chicago Tribune‘s literary supplement. From July 2013 to April 2016 she was one of four presenter/interviewers for New Zealand Hawkes Bay Television’s half hour interview program CHATROOM.