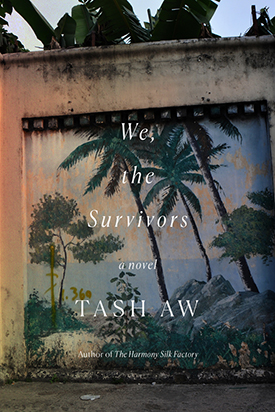

In We, the Survivors, award-winning and critically acclaimed author Tash Aw presents a compelling depiction of a man’s act of violence, set against the backdrop of Asia in flux. Ah Hock is an ordinary man of simple means—so what brings him to kill a man? This question leads a young, privileged journalist to Ah Hock’s door. While the victim has been mourned and the killer has served time for the crime, Ah Hock’s motive remains unclear, even to himself. The unfurling of Ah Hock’s confession forces both the speaker and his listener to reckon with systems of power, race, and class in a place where success is promised to all yet delivered only to its lucky heirs. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, author of the award-winning novels Purple Hibiscus, Half of a Yellow Sun, and Americanah, joined Aw in conversation at Greenlight Bookstore.

Adichie: Thank you for coming. I’m just really happy to be here because I love this man. He is one of my closest friends in the world and he wrote a book that I love. So, we’re going to talk about it.

I’ve read all of Tash’s books and you should all do so as well. There is a consistency of voice and of focus in his writing. But We, the Survivors is the book that I think is the most intimate. I want to start by asking you a very obvious question: how personal is this book?

Aw: All my books are personal to some degree. But after having written four books, it’s slowly become clear to me that I’ve settled my gaze upon examining how people in Southeast Asia and Malaysia have changed over the years and how their hopes and desires have changed over the course of the last half century. With this novel, I felt I needed to address the people closest to me: my family, my cousins.

With this novel, I felt I needed to address the people closest to me: my family, my cousins.

I come from a family that was divided between the countryside and the city. The countryside in Malaysia is not a glamorous place. It’s not a place like in France or in England, where the social elite reside. It’s a place of deprivation. No one thinks, “Oh, I would really love to live there.” People think, “I want to get the hell out of here.” And my parents were lucky enough to have done that. I grew up in the city and had a suburban upbringing. But my first cousins, with whom I grew up, they stayed in the countryside. Around about thirteen or fourteen years old, I began to pull apart. That’s the age I thought I needed to address in this novel.

The novel is about two parts of me: the part of me that is represented by my cousins who are still in the countryside, who don’t have the same opportunities as I’ve had; and the part of me represented by the life I live now. And it’s about how different we’ve become in the space of one generation.

Adichie: There’s something about the idea of finding comfort in being invisible that I was so moved by. I was almost in tears. This is a character who’s escaped; for whom being in this place is a kind of safety—because this is a story of a family escaping China, then going to Indonesia, then leaving Indonesia—and who is, somehow, always in flight; and for whom, finally, the countryside becomes a safety. He does not want to be seen and I found it very moving. I just want you to say something about that.

Aw: Sure. The book is about a man called Ah Hock, a stand-in for a lot of my cousins, the people I grew up with. He comes from an immigrant Chinese family whose ancestors came from southern China, drifted through Southeast Asia, and ended up in a small, fictional, seaside village which is only about fifty to sixty kilometers from Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia, but may as well be a different universe away. His parents, like everyone in that village, are fishermen. Either they go up to the sea or they tend to work in the factories nearby. It’s a tough life, by any objective measure. This is exactly the type of family that my aunt came from. And growing up, when I’d speak to people of her village, none of them would say that they had tough lives. What else can you do in those situations? You have a certain human pride; you want your life to be normal.

In the trial, which comes later in the story, when Ah Hock’s life is described by his lawyer in terms of misery, he rebels against it. This man was born into a generation that had been told that they could do anything. That they could change their lives. For them, America was this great example of how you could change any aspect of your life by sheer willpower. But that society is very quickly becoming hierarchical. The rich are cementing their wealth and power, and for those who don’t have an education, things are really tough. You can try as much as you want but your life will always be a struggle. The vast majority of people in Malaysia are trapped—they’re not dying of hunger, but it’s hard for them to make ends meet. So Ah Hock gets pushed more and more into a corner and he ends up committing an act of terrible violence. He ends up killing a Bangladeshi migrant worker. There are millions of migrant workers in Malaysia now. It’s a racist act. It’s an act of incredible violence, but he himself doesn’t think of himself as being racist or in any way violent.

Adichie: I know it’s your book, but I’m actually going to disagree with you. I think I would need you to convince me that it was a racist act and that he was racist. I remember reading a review of your book and it said “he commits an act of senseless violence,” and I thought actually it’s not senseless.

Aw: I agree. People are very sharply divided between thinking it’s a senseless act and thinking that it is formed by the structures of society. I think that, on the face of it, it seems to have no motive. But actually, when you examine the circumstances of his life, it’s totally the product of living in a society that discriminates against him at every turn, that denies him pride and denies him opportunities at every turn. So, when he is offered a chance to act in the same way, it’s very natural that he reproduces this behavior. Every week in Malaysia, if you open the papers, you’ll read about some act of so-called senseless violence, often involving migrant workers, often things that bear no correlation to what people say was the cause of the violence.

But then when you realize that these people have been deprived of every single kind of human dignity—they work eighteen hours a day, seven days a week. They have no days off. They’re not allowed to get married. They’re not allowed to get pregnant.

Adichie: They’re not allowed to get married? They’re not allowed to get pregnant?

Aw: This is why I get so worked up by this. Foreign workers in Malaysia are brought in by agencies, sanctioned by the government, to work on strict three-year contracts. Under the terms of those work permits, they are not allowed to get married. If they become pregnant, they will have their work permit withdrawn and they will be deported from the country. What that means is that we don’t want foreign people to have any sort of emotional life, we don’t want them to have any sort of attachment to the country. We don’t want them to take any part in society. The only problem is that without them we don’t have a society.

The book is really about divisions. It’s about the division between rich Malaysians and poor Malaysians, the division between men and women, the division between queer and straight, the division between so-called foreign and so-called local. Often, these divisions aren’t clear and that’s what I was trying to show in the book.

Adichie: I was thinking that your very eloquent description of the foreign workers sounds like something we might apply to this country, considering the rhetoric around immigration in this country and the wilful denial of how important and central immigrants are to this country. But here is another lovely bit that I wanted to talk about. Is it fair to say that there is a kind of fatalism in your worldview? You write that the people in the countryside dream about being tycoons, but they never will be tycoons. You write that people dream only about the things that they know they will never have—that just felt like cold water being splashed in my face. I understand that in a way, and it made me start thinking . . .

Aw: We talked about this when I was in Lagos recently, about how people are starting to realize that the problem with many of the countries in Asia and Africa which are talked about being economically prosperous and promising is that that wealth is in the hands of a small number of people. Whatever wealth is increasing, it is increasing only in the hands of certain people. The rest of the population is being excluded from that growth. What they do have is aspirations.

Adichie: So, my question is, do you think they know? I mean I know that one of the things that capitalism has managed to do so well is convince us of things that are not true.

One of the things that capitalism has managed to do so well is convince us of things that are not true.

Aw: Yeah, absolutely.

Adichie: I think that the people who dream about being tycoons might know, in a way, that maybe they won’t be tycoons. Otherwise, the cycle cannot possibly continue.

There is an honesty in this novel that I felt was really connecting. I find, when reading fiction, I am increasingly looking for that kind of honesty. I think that it is difficult to do as a writer; it is much easier to be wishy-washy. It’s what I like to call hiding behind art. You just refuse to hide behind art. And one of the ways you do that is in the way you write about the love formulations, especially when the character is talking about his childhood. There is a nostalgia there. But, also, you’re so clear-eyed about Malaysia, about its problems, about its racism, about how dark skin has meaning in Malaysia. I’m curious about how this book has been received in Malaysia, and I ask that as a person who writes about Nigeria and who is read outside of Nigeria. The relationship with the home country is often quite contested, especially when you’re writing about it truthfully and refusing to hide.

Aw: This is something we’ve talked about for years. Every writer, and I’m speaking specifically about Malaysian writers, knows that if you live in New York and you want to write seriously about Malaysia, the first thing you think about is how much are people going to hate you. Because, you know, Malaysians, like Nigerians, are very open people. We’re very argumentative, we talk about very uncomfortable things amongst ourselves, but the moment the conversation is opened to the public, the moment it is opened to an international audience, automatically, it becomes a problem. I wrote an op-ed for The New York Times when the Malaysian plane went missing and I just stated the facts. Malaysia has a racially discriminatory political system; it has a dysfunctional government—none of which is a surprise. I mean, these are just facts. Coming from Malaysia and having press conferences with CNN, and The New York Times, and The Washington Post, I just kept thinking, “This country is really dysfunctional.” No one is giving us any answers. The government ministers are coming out, but no one is doing anything. No one is saying anything. And no one knows anything. So, all I said was welcome to our daily reality, this is what we live with all the time. This is said frequently in Malaysia, but the moment it is said in The New York Times, it becomes an issue. I had to turn off my notifications. I mean, the number of abusive emails that I got, the number of death threats, all the rest of it. It was ridiculous. It is an issue, but what I had to do with this book was just write the book that I wanted to write. I had to think about how this book represented two parts of myself and how it represents two parts of Malaysia—rather, many parts of Malaysia. I’m always slightly stressed when I’m in Malaysia to do public events because I don’t know who will be there. Will there be some establishment figure waiting to ask me questions? And now, Malaysia has had a really big change in government. Imagine only having the Republican Party in power, governing your country, forever, and suddenly changing that for a version that is slightly better. We’re not sure how it will end up, but it’s just better. Because of that people feel freer. Maybe people just needed to see their real selves in a book, their real, messy selves. Maybe they need to see how the characters in the novel are arguing about things that we all argue about. These are specifically Malaysian problems, but I also think they are universal.

A lot of people in Malaysia say that they feel very uncomfortable and implicated by the book. But I wanted to implicate myself, as the writer and as the reader. I wanted to feel guilty, to question my relationship to the rest of society.

Adichie: Is there a sadness, and if it’s not a sadness, then what is it when you are trying to navigate those two yous? When you go and see your cousins in the countryside, what is it like? Because now you are this world-travelling, cheese-eating, olive-eating, Paris-residing sophisticate, I mean: what is it like?

Aw: It’s difficult. I wrote a short essay that was published as a small book, it was called The Face, and it was about how it feels to be suddenly divorced from the people who are dearest to you because you have an education and because that education takes you in different places. I had no idea of being different from my cousins until the age of twelve or thirteen, none at all. We knew all the words to all the same songs, we ate the same foods, we all hung out together. Then, suddenly, things were different. I don’t know when or how things became different. I just remember suddenly noticing that my grammar was different, my syntax was different. I’m not so good with hockey and slang anymore. I’m not so good at being one of them. And now, thirty years later, it’s painful. To be honest, I do feel guilty sometimes when I see how our lives have panned out. If one of their children is sick, as has happened too recently, it’s suddenly a matter of life and death because they can’t pay for it. In Malaysia, we don’t have social security. If you can’t pay for the hospital costs, then your child will die. Yet, that’s not a problem that I have because I don’t have children, nor is it for my sister, who does. That’s how stark it is. Some people say that the book is uncomfortable, that I’m sending them up, making fun of class differences in Malaysia. But actually, I’m not. Literature is written by people like me who have an education, and we have a way of writing about ourselves that irons out the creases, making ourselves more presentable.

Everyone here who has Asian parents knows that intense embarrassment you feel when you have your friends over. You’re waiting for your mum or dad to say something embarrassing, something really awkward. You know just recently, just last month, I had some friends over and my mother had some food out and my friend very reasonably said: I’m a vegetarian. It was an awkward moment and my mom said, “Eat some chicken.” I don’t know how to describe it but it is really well-meaning. On the other hand, if you’re vegetarian, it’s not nice to have someone try to make you eat chicken.

Adichie: I think it depends on the context! Honestly if that vegetarian took offense, I would want to slap that vegetarian. Isn’t there something about being part of this class of people who have managed to benefit from the New Asia, the new materialistic Asia? You know, hanging out in coffee shops in Kuala Lumpur while at the same time unable to make the distinction between someone who is deliberately insulting your choice of being a vegetarian and someone who is simply coming from a cultural world where she doesn’t understand why you would choose not to eat meat.

Aw: There’s a new generation of people who are trying to reconfigure things and it requires a certain conviction, a certain courage. It requires a certain intransigence. If you don’t have any of that, then you can’t change. This is what’s happening in Malaysia right now. It’s a nuanced situation because the argument that is used by conservative reactionaries, in order to have the system to continue, is that progressive ideals are Western notions. That is always the big criticism that is dished out: you’ve become too Western. If you fight for women’s rights, you’re Westernized.

Adichie: They always tell me: “You write books for white people. That’s not our culture.”

Aw: For that reason, it is difficult for me to be judgmental.

Adichie: Now, I want us to talk about racism . . . that very exciting subject. Partly because there was something refreshing about reading a book that is about racism but isn’t about white people, because I think, again, for us—by which I mean educated, privileged people in America—racism is really a white thing. But when you’re from Asia, it’s not. I found that really refreshing about your book. What this book does is that it forces us to remember a reality about the world which is that white people don’t own racism. They own racism here. I’m interested in the hierarchies that people in Burma—in Malaysia, do they say Burma or Myanmar?

Aw: Myanmar, probably.

Adichie: And people from Bangladesh, and Nigerians—we should talk about Nigerians in Malaysia. I’m interested in the complexities of racism, the way that it works in Malaysia. Also, I’m curious about how you focus a lot on the foreigners. But what about internal Malaysia? The Malays, the Chinese Malaysians—what are they like?

Aw: It’s incredibly dysfunctional and it’s kind of a handful for anyone who doesn’t live in the country. I’ll explain the situation to people who are not Malaysian and they will have difficulty believing that it exists. Malaysia has institutionalized racism where if you belong to the majority race which is Malay, you have very obvious privileges. Fifty-one percent of every company has to be owned by an ethnic Malay. There are quotas for getting into universities. Everything is designed to exclude the Chinese, Indians, and other races. But when you grow up in that system, you become so habituated to it that it doesn’t even seem weird. It’s unfair, but what can you do about it? When you have no choice, your life either sinks into this puddle of rage or you just continue as normal. That’s why you are able to have people function in society in a way that on the surface seems all right. You’ll go to Malaysia and think that everyone is fine, that everyone is getting along. But underneath that, there is a lot of rage and resentment. That’s why I think that Ah Hock has this slightly detached response to the violent inequality of the system in which he lives because what else can he do?

The novel takes the form of interviews with Su-Min. She is an educated person, a journalist, a PhD candidate at Columbia, and she is writing up her interviews into a book. So Ah Hock is addressing her, he’s saying ‘you’ all the time and really what the reader feels often, is implicated. I wanted to implicate myself as the writer and as the reader, to question my relationship to the rest of society. Su-Min has an education, she has money, she has the cultural capital and the economic capital; she probably comes from a wealthy family that has connections. For them, they feel like politics can change. Politics can affect their lives, but for him it doesn’t matter. People in government can come and go but his life will stay the same. Bearing that in mind, what’s the point? More and more, not just in Asia, but in the whole world, Britain, France, or even America, you may have really strong feelings about whoever it is in power, but how can you change them? How can you dislodge them? It’s that frustration that so many of us have to live with. Are we thriving or are we just surviving?

It’s that frustration that so many of us have to live with. Are we thriving or are we just surviving?

Adichie: That’s a bit depressing. I think I’ve been infected by that American desire for hope. Do you think there is hope at the end of the book?

Aw: I think it’s nuanced. Oddly enough, I think hope resides in Su-Min.

Adichie: Really? I think it’s in Ah Hock.

Aw: Do you think?

Adichie: Yeah. I think he’s a very compelling character for a number of reasons. There is honesty. But I think that the comparison is maybe unfair because there is not a balance. She has power because the story is filtered through her eyes in many ways, and yet she is still not really that present. It’s hard to really make sense of her. But he, I thought, was really compelling.

Can we talk about Nigerians in Malaysia? I was telling Tash earlier that there is a big population of Nigerians in Malaysia, but not just Nigerians but the Igbo people. Ninety-seven percent Igbo. Young Igbo men who are loosely traders. And now there is a stereotype of the Nigerians that live in Malaysia. If you are a young man and you come back (usually at Christmas), when somebody says “he was in Malaysia,” there is a tone that implies dodgy. It implies that he is either trading in drugs or fraud. It started off with Nigerians going to Malaysia to go to school, maybe fifteen years ago. There is a bit in the book that made me laugh where Ah Hock says something like, “I noticed the Nigerians coming and I thought where you are coming from must be really bad if you had to come here.” I thought that was hilarious. But I think it has changed a little or maybe it’s the people who came to those schools and stayed who stayed and became dodgy.

Aw: I know this stereotype because it is exactly the stereotype that Malaysians have of Nigerians. I spend all my time arguing against that.

Adichie: See, Tash—this is exactly what this book is about, what we just said. You’re doing the PhD person and I’m doing Ah Hock right now. So, Nigerians, if you ask the average Nigerian about Nigerians in Malaysia, they’ll just tell you. But, of course, that doesn’t mean that’s what all Nigerians do in Malaysia, right? But it’s the story that sticks. There’s a scene in the book, and I’m curious about, again, how it’s received and if you know what you were thinking. In writing that scene in which Nigerians are the subject of, really, police brutality—what were you thinking? Do you know what you were thinking?

Aw: Not really. A lot of the book is just about—well, I’m just so close to the characters, the characters are really part of me. It’s really about capturing what they see and what they feel is happening in Malaysian society. Just seeing groups of African men and hearing what’s said about them and reading about them in the papers. In that passage he talks about being aware that they’re Nigerians and being aware that they’re in the country on student Visas. To the rest of Malaysia, they’re just black guys. And it’s a very derogatory word that’s used all the time—it’s used in the national press.

Adichie: Sounds similar.

Aw: I know. It’s used in editorials in the main Malay language newspaper. And it’s one of those generalized derogatory terms that has no acknowledgement of the fact that these are human beings who have come to Malaysia often with a legal visa, and confine themselves. They finish their degree and get to doing what are they came to do. Like so many other immigrants in Malaysia, they come because they want to make a better life. So, this thing, going back to your own country during Christmastime, bearing gifts, bearing money, that’s a very universal thing. It’s what Malaysians do. You go back to the village, at the festivals, with a ton of cash, with presents. It’s something we understand so well. But somehow, when it’s Africans, we pretend that we don’t know why they’re in this country. Like, why are they here? And it’s this sort of lack of comprehension that I find very troubling and I wanted to address in the book. Ah Hock makes very little attempt to penetrate that because, like most Malaysians, he doesn’t have access to any information, he doesn’t care about them.

Adichie: I felt like that was really honest. I think as a reader I would have disbelieved if you’d written a wonderful, communist, crusading, human rights person. But the way that it’s done, we as readers are forced to confront the humanity of these Nigerians. It’s very subtle, but I think it’s still very powerful because what’s being done, that’s what we’re being shown. They are playing their music too loud and the police come and harass them.

Aw: They’re playing their music. “Too loud” is what the police say.

Adichie: Of course. But this is what I remember thinking: that this is how the psychology of trauma works because a tiny part of me thought maybe don’t play your music so loud and I think sometimes I find myself becoming complicit.

Aw: That’s what I wanted to do with the book. I wanted the reader to be invited into this whole very uncomfortable and dysfunctional structure and at every point to be complicit in it—to try and tease out why exactly we feel so uncomfortable.

Adichie: I guess injustice has become familiar and almost normal.

Tash Aw was born in Taipei and brought up in Malaysia. He is the author of The Harmony Silk Factory, which was the winner of the Whitbread First Novel Award and the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best First Novel and was long-listed for the Man Booker Prize; Map of the Invisible World; and Five Star Billionaire, also longlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2013. He is also the author of a memoir of an immigrant family, The Face: Strangers on a Pier, a finalist for the LA Times Book Prize.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is the author of award-winning and bestselling novels, including Americanah and Half of a Yellow Sun; the short story collection The Thing Around Your Neck; and the essay We Should All Be Feminists. A recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, she divides her time between the United States and Nigeria.