Editor and publisher Robert Giroux worked with some of the most esteemed writers of his day, including Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell, Bernard Malamud, and many other giants of twentieth-century literature. In 1964, the company’s name was changed to Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He was semi-retired when I started at FSG as an editorial assistant in 1993, but I helped him one day a week with his correspondence, and I’d shepherd his occasional books through the production process—posthumous work by Isaac Bashevis Singer, a biography of Walker Percy. He would sometimes take me to lunch at the Century Club, where we’d first stop at the bar for a whiskey and soda before ordering. He was a terrific storyteller, and I marveled at his anecdotes about T.S. Eliot asking him, editor to editor, whether he had much “author trouble,” or about having to drive around Manhattan all night in a taxi with Robert Lowell when Lowell was having a nervous breakdown. Or bumping into “Jerry” Salinger at the Grand Central Oyster Bar where they discussed his early stories that had begun to appear in The New Yorker, or visiting Flannery and her peacocks in Milledgeville. For years, Mr. Giroux—as anyone under forty at the firm learned to call him—had been rumored to be working on a memoir about his career in publishing. At some point before I left FSG in 2003, I offered to enter anything he’d written into a computer (he worked on a typewriter). So far as I know, the first chapter that follows is all that has survived of a book that many of us wish we could read.

—Ethan Nosowsky (Editorial Director at Graywolf Press)

When I started as an editor in the late thirties, book publishing in America enjoyed a different character from today’s global industry with its foreign and domestic mega-mergers, “acquisitions” editors who don’t edit, and literary super-agents. The adversarial relationship between authors and publishers was always a fact of life but big advances were rare. My impression that authors and books were different in those days may be the product of a youthful bias: I was only twenty-five when I landed my first job at Harcourt Brace and Company on the lowest rung of the editorial ladder. It was late in December 1938 when Frank Morley hired me. Donald Brace had recently persuaded Frank to move from the London house of Faber & Faber to New York as manager of the trade department, as well as the editor-in-chief. When I started on the first workday of January 1940, the Depression was not quite over, the war in Europe had just begun, and I’d left a better paying job at CBS Radio—and was happy to do so—because I’d been determined to enter the book world and become an editor on leaving college in 1936.

When I joined it, Harcourt Brace was twenty years old, with the reputation of being an enterprising and progressive house. It had started in 1919, right after World War I, and its early lists reflected the adventurous spirit of the twenties. They published black writers like W.E.B. DuBois and Arna Bontemps; novelists like Sinclair Lewis, Virginia Woolf, and E.M. Forster; critics like Constance Rourke and Lewis Mumford; biographers like Paul de Kruif and Lytton Strachey; and poets like T.S. Eliot and Carl Sandburg. During my first month it struck me as extraordinary that Morley should ask an inexperienced editor his opinion of a manuscript by Edmund Wilson. Was this a kind of test for a first reader? As I devoured the pages of To the Finland Station, I realized I was reading a masterpiece. It was a brilliantly written history of the development of socialist thought. It started with Giovanni Vico’s cyclical theory of history set forth in his 1725 work, Scienza Nuova, tracked Vico’s influence on the French historian Jules Michelet, and ended with Michelet’s effect on the thinking of Marx, Engels, and Lenin. Wilson’s rather puzzling title made sense when you learned that in 1917 the Germans, who had imprisoned Lenin, released him in the hope he’d get Russia out of the war—which he did. When his guarded train left Germany and arrived at the Finland Station in St. Petersburg, modern political history can be said to have begun. After Morley read my glowing report that To the Finland Station deserved hosannas, he merely smiled and said, “Yes, isn’t Wilson a marvelous writer? I wonder how well the book will do.” On publication it received condescending reviews and sold around 4,000 copies. Years later it was reissued in the new Anchor Books paperback series with success and finally, in 1971, when my present firm—Farrar, Straus and Giroux—reissued it in hardcovers, the rave review on the front page of The New York Times Book Review said that no one in 1940 appreciated the book’s importance (ha ha). This sobering lesson taught me that some great books are ahead of their times and that the trick is how to keep them afloat until the times catch up.

This sobering lesson taught me that some great books are ahead of their times and that the trick is how to keep them afloat until the times catch up.

I’d had a glimpse of this disillusioning truth at Columbia College from a great teacher, Professor Raymond Weaver, the first biographer of Herman Melville. The story he told us hit me like a revelation, a kind of epiphany, and inspired my ambition to be a book editor. My Columbia scholarship had given me the option of entering the School of Journalism in my junior year, but Weaver’s story changed everything. He told us that Moby Dick, published by Harpers in 1851, had been a real flop, a disaster so complete that Melville never recovered as a writer. He knew the novel was his masterpiece, and we know it, so why didn’t the reading public of the 1850s recognize its great qualities? The Athenaeum in London called it “an absurd book, so much trash belonging to the worst School of Bedlam literature.” Yet the young Longfellow (Melville never knew this) wrote in his journal: “Read all evening Melville’s new book, ‘Moby Dick or the Whale.’ Very wild, strange, and interesting.” Melville’s income fell so low that he had to take a job in the New York Customs offices at Battery Park, where he worked for twenty years, walking downtown each day from his house on East 26th Street. By 1891 he was so forgotten that the New York newspapers missed the news of his death. Weaver said that in 1912, while researching his biography, he visited Melville’s granddaughter, Mrs. Metcalf, in the house on 26th Street, where she showed him a small trunk of her grandfather’s papers she had recently received. Weaver was the first person to read the manuscript of Billy Budd, which lay in the trunk in Melville’s crabbed handwriting, completed only a few weeks before his death. A small masterpiece that might easily have been lost, it was edited by Weaver and published in 1924 by Horace Liveright in an anthology of Melville’s shorter fiction.

• • •

Alfred Harcourt and Donald Brace were members of the class of 1904 at Columbia College and they worked as editors of the undergraduate newspaper, The Spectator. On graduation, after working for fifteen years at Henry Holt, a publishing house dating from the post-Civil War period, they decided in 1919 to launch their own firm. It was then possible to start a new house with limited capital (Alfred Knopf had done it only a few years earlier), though they welcomed the financial help offered by a wealthy friend, another Columbian who became the firm’s silent partner—the legendary Joel Spingarn. His estate at Amenia, New York was said to be “a botanist’s paradise.” For twelve years he had been Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University when, in 1910, he clashed with President Nicholas Murray Butler over a question of academic freedom. The classics scholar Harry Thurston Peck, holder for twenty-eight years of the prestigious chair of Anthon Professor of Latin and Greek, had become involved in a threatened breach of promise suit. He was smeared when the woman’s allegations became public after she released his letters not in court but to the newspapers. Butler promptly fired Peck, who later killed himself. Spingarn protested Peck’s dismissal without a hearing, and Butler fired Spingarn for insubordination in 1911. (After he left academia, Spingarn played a historic and crucial role in helping W.E.B. DuBois to found the NAACP. DuBois was the first black man to be granted a PhD by Harvard, where he had been sponsored by William James. Spingarn served as the chairman of the NAACP until 1919, as treasurer until 1930, and as president until his death in 1939.) At Harcourt Brace he launched a “European Library,” including the works of Benedetto Croce, Jacob Wasserman, Heinrich Mann, Walther Rathenau, Giovanni Papini, and Rémy de Gourmont. He also brought to the list De Sanctis’s great History of Italian Literature, Harold Stearns’s anthology Civilization in the United States, and DuBois’s pioneering post-Civil War history, Reconstruction. (During my first year at the firm I edited DuBois’s memoir Dusk of Dawn and though I never met the elderly author, we corresponded and talked on the phone. I admired his old-fashioned courtly manner and very modern intellectual vitality.) After the start of World War I Spingarn became a major in U.S. Army Intelligence. He helped to break the color barrier against black officers by getting DuBois commissioned as an army captain, over great opposition. His many roles—fighting racism and academic injustice so early, helping to found Harcourt Brace, and leaving his imprint on the firm where I worked for fifteen years—have not been properly recorded. This “prince among men,” as DuBois called him in dedicating Dusk of Dawn, deserves honor as a hero of the intellectual history of America.

From the start Harcourt Brace was a great success. In their first twelve months they brought out three extraordinary bestsellers—Sinclair Lewis’s novel, Main Street; Maynard Keynes’s report on the Versailles Conference, The Economic Consequences of the Peace; and Lytton Strachey’s debunking biography, Queen Victoria. Young Lewis, whose early novels were issued by Doubleday, Doran, was a close friend of Harcourt’s whom he not only urged to break away from Holt’s ultra-conservative policies and start his own house, but put up a few thousand dollars of his own. The publication of Main Street placed him for the first time in the ranks of serious American writers. The four novels that followed—Babbitt, Arrowsmith, Elmer Gantry, and Dodsworth—made him America’s first Nobel Prize laureate. After his marriage to journalist Dorothy Thompson, she believed (and convinced him) that the firm was not according him proper respect in his new international status. The letter Harcourt wrote on Lewis’s departure in 1931 is a classic, with these closing words: “I know, Red, you have some idea of how sorry I am that events have taken this turn. You and we have been so closely associated in our youth and growth that I wish we might have gone the rest of the way together. If I’ve lost an author, you haven’t lost either a friend or a devoted reader.”

“If I’ve lost an author, you haven’t lost either a friend or a devoted reader.”

As for the Keynes book, it came to Harcourt because Walter Lippmann, a young reporter on the staff of the newly founded The New Republic, who covered the Versailles summit, advised Harcourt by cable to make an offer for Keynes’s work-in-progress. It was a blistering critique of the conference’s short-sighted shenanigans, the writing was brilliant, and the book could be a best-seller. After Keynes accepted an offer in pounds and the rate of exchange altered in favor of dollars, Harcourt assured Keynes the firm would honor the advance as originally understood. Keynes was so impressed that he in turn sent Lytton Strachey, Virginia and Leonard Woolf, E.M. Forster, Roger Fry, and all the other Bloomsberries to this unusual American publisher. That is why their books still grace the Harcourt Brace list. The Economic Consequences of the Peace quickly sold out its first printing. Mr. Brace told me the demand was so great that many senators dispatched page-boys from Washington to New York (the offices were then located at 1 West 47th Street, in the basement and first floor of a private brownstone house) to obtain copies of the book. All hands, including the founders, wrapped and shipped the books as fast as they came from Quinn & Boden in New Jersey. The big debate over U.S. membership in the proposed League of Nations was raging and Keynes’s book was packed with hard facts for Washington’s ill-informed solons.

Harcourt’s third coup took place in London, where he sailed to meet Keynes before the book was published. When he heard that Strachey’s Queen Victoria had only just been delivered to the old-line house that published his previous books, Harcourt told me he called at their offices but, since he was new and unknown, the principals would not see him and a junior haughtily told him his name would go at the end of a long list. When Keynes introduced him to Strachey later that day, Harcourt asked him if he automatically ceded the American rights of his books to his London publisher. Strachey said he had not yet contracted for the book and had not yet heard from the publisher, adding, “I do nothing automatically.” None of his books had done particularly well in America, he said, and what exactly did Harcourt have in mind? The whopping offer (for those days) Harcourt made for the U.S. rights to Queen Victoria was accepted, to the chagrin of the old-line house.

Donald Brace became a friend of Virginia and Leonard Woolf, whom he often met on his annual visits to England. In the summer of 1941 he handed me the Hogarth Press proofs of her posthumous novel, Between the Acts. Of course there was nothing to edit but I was thrilled to be involved, even mechanically, with an author whose work I admired. This last novel of hers is a portrait of England entre les deux guerres, between 1918 and 1939—thus her title. A group of upper-middle-class characters are staging a village pageant, a sort of review of England’s history. This neglected and brilliant novel belongs with her best, but I had no idea in 1941 that it was prophetic of England’s future.

It was in March 1941 that Brace called me into his office and handed me Woolf’s heartbreaking account of his wife’s suicide. She had long suffered from bouts of depression but after the outbreak of war, when England’s early reverses grew worse, her sense of doom became unbearable. Not only had she seen the ruins of bombed-out sites in London, but she told Leonard she could spot with her own eyes the Nazi insignia on the German planes that flew over their house in the country. She also told her husband in two notes left on her desk that she was losing her mind. On the morning of her death she told him she was going for a walk, put on boots and a fur coat (it was mid-March), took her walking stick, and got as far as the River Ouse, which flowed near their house at Rodmell in Sussex. Near the river she found a heavy stone and fit it into her coat pocket, walked into the water, and drowned herself. At lunchtime when Leonard missed her, he ran to the river, discovered her boot prints on the bank, and spotted her walking stick floating in the water—but there was no sign of her body. Weeks later it was discovered miles upriver, still wrapped in the fur coat.

When later I sent to press her posthumous book of essays, The Death of the Moth, I was scolded on the phone by George Davis, the literary editor of Harper’s Bazaar, for not having sent him an early set of proofs. “I alone,” he informed me, “have serialized her essays in our magazine.” When I asked what his fashionable and expensive magazine paid, he said, “Twenty-five dollars an essay.” I was so shocked that I answered, “Not anymore. It’s now one hundred dollars,” and he angrily agreed. Leonard Woolf then wrote Mr. Brace a charming note: “The four hundred percent increase for the essays is much appreciated.”

• • •

On graduation from college I had tried to find an opening in book publishing—even non-editorial—without success. I knew I was lucky (because jobs were so scarce) when my friend and classmate, Robert Paul Smith, told me CBS was starting an “apprenticeship” program of beginners and I was hired at twenty-five dollars a week, which was above-average in those days. Bob was enjoying a high-paying job at CBS, writing continuity for the big band programs sponsored by cigarette companies. I later published his first novel, So It Doesn’t Whistle, which sold reasonably well, but his second book, ingeniously entitled Where Did you Go? Out. What Did You Do? Nothing, about children vs. parents, became a bestseller. CBS was then located at 383 Madison Avenue on the southeast corner of 52nd Street, across from Alfred Knopf’s on the northeast corner—as I was very much aware, since I greatly admired the House of Knopf.

At CBS—this was before television of course—one interviewer asked me if I had any “new ideas” for radio, and when I suggested that the sessions of Congress might be taped and edited once a week into an hour’s broadcast, there was a scornful response: “Do you think we’re in the business of boring people to death?” A few interviews later I hit it off with Victor Ratner, the head of the sales promotion department, the last place I expected to end up in. Vic was a well-read, creative, and imaginative young executive, who stammered. When I proposed in our interview that CBS might issue a monthly program booklet, he said: “Why haven’t we thought of this before?” and hired me on the spot. I got a ten-dollar raise the following January and a bound set of the first year’s program booklets, which I still have.

In 1937–38 fear of the impending world war grew as Adolf Hitler’s appalling rise to power took place. With the Nazi seizure of Austria—the Anschluss as it was called—our worries intensified. I began to collect the scripts of CBS’s European “roundup” broadcasts and submitted them to Vic, with a memo proposing their publication in a book entitled The Sound of History. After hesitating, CBS finally published the edited texts in a paperback with a laminated cover in red, yellow, and black, showing massed Nazi troops on the march. It bore the title Vienna: March 1938 and a subtitle, A Footnote for Historians. Covering the thirty days from March 11 to April 10, it quoted the words of Hitler, Schuschnigg, Chamberlain, Daladier, Mussolini, Roosevelt, and others as they were heard over CBS Radio, together with the commentaries of William Shirer, Edward Murrow, Eric Sevareid, H. V. Kaltenborn, and others on the CBS news staff. The book opened with Hitler’s lie: “On Friday night I was not even thinking of Austria. Then suddenly I knew that the deed and the hour were predetermined . . . I did not consult anyone. I gave orders.” That this was a lie was proved by the fact that CBS at 5:29 (Vienna time) had flashed the news that Chancellor Schuschnigg had postponed the proposed referendum on whether Austria should join Germany, followed at 7:15 by news of the chancellor’s resignation. By 7:45 German troops were crossing the border and at 8:43 the swastika was flying over the chancellery. It was a frightening and fantastic coup. The response of the radio industry to the booklet was so great, and Hitler’s subsequent political and military successes were so incredible that a second book became inevitable. That fall CBS issued a hardcover volume entitled Crisis: September 1939, recounting Neville Chamberlain’s “peace journey” to Munich and his smiling return to London airport, waving a worthless scrap of paper. The horrors of World War II started officially that month.

While we were editing Crisis, Vic took me upstairs to the CBS executive offices, which I had never seen. William Paley was out of town, so we went into the office of Paul Kesten, Vic’s boss, whose nickname was “Vice President in Charge of the Future.” Kesten’s editorial suggestions for the book were excellent and his congratulations were music to my ears. I expected another raise, which did not come, so I was now ready to leave CBS whenever I could find an opening in book publishing. In this period of fear Orson Welles’s radio drama, “The War of the Worlds”—his report of an imaginary Martian invasion of New Jersey—was so realistic that it frightened and even terrorized the public. Mailbags of protest letters from outraged listeners started to pile up on tables in the corridors. I’ve never forgotten one letter from a young woman who wrote that on the night of the Welles broadcast (about which she knew nothing, but which her mother had been listening to) she got home from work just after it ended. At her doorstep she tripped and fell, cutting her forehead. When her mother opened the door and saw blood on her forehead, she screamed: “My God, have those awful Martians hurt you?”

I shared a small office at CBS with Herbert Bayard Swope Jr., the son of the famous 1920s editor of the old New York World. Young Swope knew Eleanor Roosevelt and asked me and a group of friends late in 1939 to meet the first lady. It seemed extraordinary to me that she would take the time to speak to a group of young people worried about the war. Among the guests was an elegantly dressed young French woman whose dark red fingernails bore ten white letters reading, “A BAS HITLER.” The trouble was that her left hand read “A-B-A-S-H” and the right “I-T-L-E-R.” If Mrs. Roosevelt or anyone else noticed this pitiful cosmetic message, they were too polite to say so, but it has stuck in my mind as a symbol of this helpless era. The first lady’s brief talk to us was wonderful and somehow reassuring, even though she mentioned the fierce and highly vocal opposition to America’s involvement in the war from isolationists in and out of Congress. That very week a friend told me there might be an opening at Harcourt Brace and I wrote for an interview.

Frank Morley was an impressive man, tall, with an enormous chest (because of which Ezra Pound dubbed him “The Whale”). His clear eyes and prominent nose reminded me of Holbein’s portrait of Thomas More. He looked at my vita and said, “So you’ve written film reviews for The Nation and you edited the literary magazine at college. Have you thought of writing books on your own?”

“Yes,” I said, “I’ve thought about it but haven’t yet done so, though I did publish two books at CBS. They were compilations of radio broadcasts, not original writing.”

“You mean you did those books on the invasion of Austria and the Munich crisis?” Morley said he had tried to get the publishing rights for Faber, but CBS would not release them for England. I had not even listed the books in my vita and was amazed that he had seen them. Vic Ratner later explained that CBS feared their publication abroad might result in William Shirer’s expulsion from Berlin, where he was the sole CBS correspondent. I realized I was being hired partly because of work I had never connected with book publishing.

I realized I was being hired partly because of work I had never connected with book publishing.

• • •

One morning in September 1940 Alfred Harcourt introduced me to two strangers. They were exiled German publishers, Gottfried Bermann Fischer, the head of the distinguished house of S. Fischer Verlag, the management of which he took over after the death of its founder, his father-in-law. His colleague was L.H. Landshoff and their first book in America (in German) was Thomas Mann’s Lotte im Weimar, which Knopf issued in English a year later. Quinn & Boden, Harcourt’s printer, produced a handsome German-looking book, small and compact, elegantly printed. Mann himself was also in exile in this country. They used their office next to mine until they launched their new firm, L.B. Fischer, with a list of books in English. They were the guests of Mr. Harcourt and their books were distributed by our firm the first year. A betrayal of civilization and a terrible crime against human beings had begun, the full horror of which was not fully understood until after the war when we saw it in photos and newsreels and read documents like Eugene Kogon’s history, Der SS Stadt, published in America as The Theory and Practice of Hell.

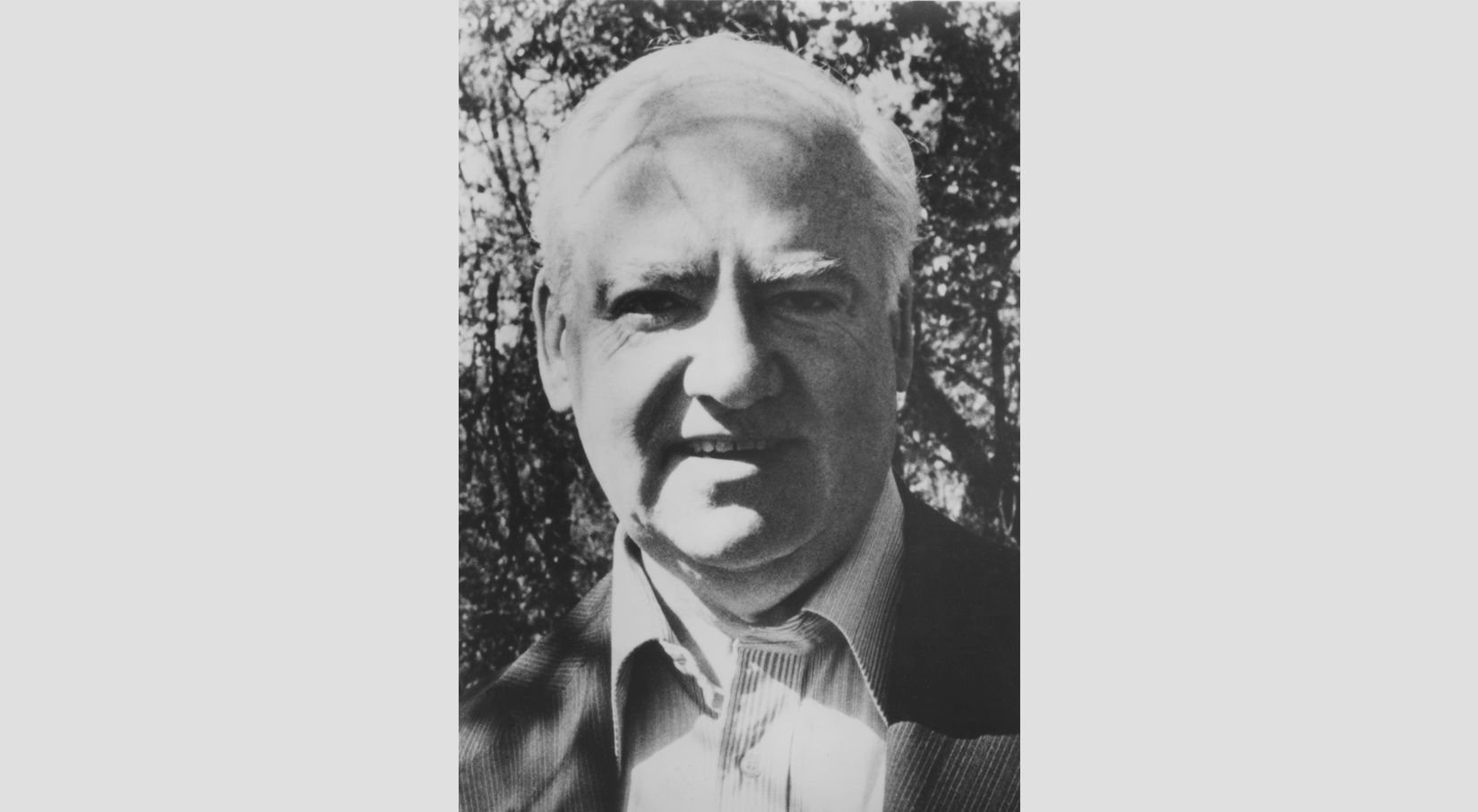

Robert Giroux (1914-2008) was an American book editor and publisher. Starting his editing career with Harcourt, Brace & Co., he was hired away to work for Roger W. Straus, Jr. at Farrar & Straus in 1955, where he became a partner and, eventually, its chairman. He fostered authors Jack Kerouac, Susan Sontag and Robert Lowell, and many more.