As part of our ongoing celebration of National Poetry Month we spoke with poet, designer, and longtime FSG collaborator Jeff Clark about his creative process, the ins and outs of creating distinctive and powerful book covers, and some of his many and varied influences. Clark has designed jackets for FSG since 2002 including Giuseppe Ungaretti’s Selected Poems , John Clare’s “I Am”: The Selected Poetry of John Clare and more.

You’ve been designing book covers since 1996. What initially drew you to this work? Were you designing covers for poetry collections from the start, or did that come later?

When I finished an MFA at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop I got a job in a magazine shop in San Francisco and became kind of obsessed with the art and design magazines on the shelves. I taught myself design software, and started to do a poetry zine. At some point I heard about a book design studio in Oakland and applied to work there. They had an opening for an entry-level proofreader, and that’s how I got my start. After a couple years I moved from their proofreading room into typesetting, and a couple years after that I started doing some design—mostly of scholarly books and art catalogues. I did my own design/typesetting work after hours, for poet friends and tiny presses. That work snowballed and in 2007 I began to work full-time on my own.

You’re responsible for the cover design of many of the poetry collections published by FSG. How did that relationship come about?

Around 2002 I sent Jonathan Galassi a few books I’d designed, and asked if it would be possible to do some work for FSG. He said yes, and I designed and typeset Giuseppe Ungaretti’s Selected Poems, which in hindsight is wild because he’d been a fascist poet and I’ve become an antifascist ex-poet. My work for you all continues to this day. I carry a feeling of deep gratitude to Jonathan, and I feel so fortunate to have been able to work for twenty years alongside my buddies Abby Kagan (interiors) and Maureen Bishop (jackets).

Is your approach to designing poetry covers specific to the genre? What sets the design process for poetry apart from, say, the design process for nonfiction?

The second question I’ve been preoccupied with for some time. I don’t know precisely when it began (the ’80s?), but there’s a tradition in American poetry publishing wherein a poet gets to choose an artwork to go on their cover. In addition to the fact that too often what they choose isn’t amazing, there’s also the issue that it kneecaps the design process, which ideally springs directly from two things: 1) a designer’s reading of a writer’s manuscript and 2) a blank slate. Some poets let me work this way; quite a few don’t. I used to be more stubborn about trying to convey to poets that slapping a painting on their front cover isn’t the best decision, when instead what they could have is something informed by their writing and interwoven with the overall feeling of the book, but now if there’s time I’ll try to make an alternative concept that shows my own approach to the work. I’m pretty sure designers of books in other genres don’t have to deal with this, but it’s clear to me that there’s an impulse to let poets feel executive control over how their book looks. It’s just that doing a book like that can feel less about designing and more about doing decor.

To turn the question on its head, are there certain things that a poetry collection’s cover needs to accomplish or signal to readers? What makes the design of a poetry collection a success?

My feeling is that people are drawn to a book when their evaluative habits are obstructed, either by the uncanny (like the cover of the Cocteau Twins Victorialand), the provocative (like Richard Siken’s Crush), the incomplete/occluded (Irma Boom’s Sheila Hicks), the strident (Laure: The Collected Writings), the ultraminimal situationist international covers, but not Hal Foster’s Design and Crime), the redolent (the jacket of the 1981 first edition of Toni Morrison’s Tar Baby, encountered in 2023, or the jacket of the 1970 edition of Soledad Brother), the moving failure (the serious but cheesy cover of the first edition of Penny Rimbaud’s Shibboleth), the fast and messy (Lance Phillips’s Mimer). I’ve only listed a handful of my own favorite ways this happens. I sometimes don’t mind familiar, normative design, but it really depends on context. The UK edition of Granny Made Me an Anarchist comes to mind, and so does The 2015 Baltimore Uprising. But my assumption in saying all this is that the bookstore browser we’re discussing is like me, and many aren’t. Many people are drawn in by eye candy, cleverness, levity, the familiar, the scintillating, the apparently bourgeois—and if I’m being honest I’m probably sometimes one of them.

So maybe in addition to asking what makes a successful design, we have to also find out who is a book’s readership? People in the Hamptons might read Superstructures by Experimental Jetset or Chris Krause’s I Love Dick, but not Assata or Cindy Milstein’s Taking Sides. It’s quite complicated, which is cool. And it’s complicated in the other fields, too. For me a throwie on a storefront can be revolutionary and art at Gagosian could never be (I want to be proven wrong!). I probably do my freest work for little publishers who can’t really pay, especially if they inhabit the margins by choice.

The second part of the question is where things get even more complex. A book with a cool cover and a run-of-the-mill interior design is a design failure. That makes me sound like I’m being dismissive of publishers without any interior design budget, but what I’m actually critical of is a system that privileges the surface of things but not their insides. Even beloved Verso sometimes puts out books that are gorgeous on the outside and ugly on the inside. For me an appropriate design originates with the basic typography dead center in the book, and radiates outward to the titling, the final trim size, the paper and binding, and finally to the cover, which in my practice I try to design last. But again, everything depends on publishing context. Most of my clients can barely afford to print a book offset, so things like foilstamping and extra inks and varnishes aren’t really an option, let alone hardback binding and bellybands or other bells and whistles. Often, therefore, when I’m working I’m thinking F*ck the hegemony of the book cover—it’s just a wrapper, and it’s the least important aspect of a book once the reading experience has begun, and yet, because I’m aware the books I design go out into a society, I’m also thinking I really hope this cover blows minds, especially when it comes to books or propaganda with potentially world-changing import. I don’t think readers of casual literature want to have their minds blown by design—they want to be massaged.

When you agree to design a poetry cover, where do you begin? Do your designs ever grow out of a specific poem in a collection?

I read the manuscript and usually it gives me everything I need. I do pay attention to a poem if its title is also the title of the book—but not too much attention. It’s also important to me to find out if the author has any specific desires for the design’s overall feel. I love it when writers send “mood boards,” especially when they contain various sorts of visual material. One publisher recently forwarded me an author’s email describing the two albums they hoped I’d listen to while designing. It really works.

How do you think of the relationship between a collection’s cover and the poetry within?

Like it’s an aftereffect? Sometimes I want the cover to be a foil, at other times I just want the cover to be a signal booster. If the poems are full of guts, I want to reflect that and make it so the book goes in your bag. I want to design covers that are unfamiliar; I don’t want to make covers that are shallow and handsome and seductive because that’s what’s most common, and most of those sweet covers face-out at the bookstore are uncritical memes whose aim is to move product. Sometimes I have to make banal design, too, especially if I’m required to use art that I’m not allowed to hack or undermine or propose alternatives to.

A paradox: sometimes design is so unskilled it’s great. You don’t have to waste any time trying to filter out the packaging interventions that have been attempted on the text. A zine about mutual aid, for example, printed with black toner on white copy paper, with all-caps Times New Roman lettering centered on the trim. A designer wasn’t hired to spruce the text up or, conversely, to camouflage it—there’s just an immediate invitation to read. Sometimes “bad” or “amateur” design coming from down low is the design I distrust the least, whereas absolutely beautiful design by Prominent Jacket Designer X, for example, is likely to be on a book that isn’t trying to dismantle oppression. Unskilled design can be an indicator the work is coming from a context where “good design” may be held in suspicion, or simply disrespected, or can’t be afforded, or there’s no time for it, each of which I dig. On the other hand, some of the design I envy the most is coming from a European art context, and that scene is really aesthetically cunning, but also affluent and bloated.

I know that you design the interiors of many of the collections you work on as well. How do you conceive of the relationship between cover and interior design?

My aspiration is for them to be intertwined and mutually abetting, but I do try to devote most of my attention first to the look and feel of the interior since it’s where the actual encounter with the writing happens. It literally is the writing. Books that have a cover coming from one designer and the interior from another often end up looking as if the cover is at odds with the rest of the book.

You’re a celebrated poet in your own right. How does that inform your work as a designer?

I quit trying to write poetry in 2009, which is when my final book, called Ruins, was published. While it didn’t happen overnight (I talked about it in therapy for nearly a decade), the decision to liberate myself from writing happened to free me up to embrace my design work, rather than think of it as just something I did to earn a living.

From having studied and written poetry I feel like I know how to interpret it and convey it in book form, in which case my time as a poet could be thought of as training for my practice as a designer of books.

Do you think you have a signature as a cover designer—some sort of consistent visual language that identifies your poetry covers as the work of Jeff Clark?

I’ve been struggling with this one! My guess is that I don’t have a signature?

Could you share one of your FSG poetry covers that’s a particular favorite, and say a few words about the design?

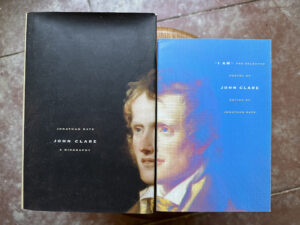

I still love how the John Clare biography and selected poems work together. I cringe at the Copperplate font! But we grow . . .

(Photo courtesy of Jeff Clark)