For this installment of “Developing Stories,” a series from Work in Progress, author Carlos Fonseca presents a series of visual pieces that guided him while writing his novel, Natural History. “Every novel is an archive or at least refers back to one. Storytelling has much to do with the experience of opening an old shoe box or a sandwich bag full of polaroids and building a narrative out of the bits and pieces that have been left behind,” Fonseca writers. “In the case of Natural History, the novel starts with the arrival of an archive. In the middle of the night the protagonist receives three files full of photographs, notes, sketches and newspaper clippings that jumpstart his journey to reconstruct the history of an enigmatic family. The experience of writing the novel was a bit like that: collecting pieces of a puzzle that suddenly became visible as the fragments began to coalesce.”

One of the unlikely occurrences that gave rise to the novel took place when, in the summer of 2011, my wife and I visited the exhibition Savage Beauty at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The British fashion designer Alexander McQueen had been dead one year and the show was meant as a retrospective of his work. Instead of the frivolities I expected, I was surprised to find a fascinating exploration of fashion as the meeting point between art, humanity and animality.

Savage Beauty by Alexander McQueen, 2015. Photo credit: Isabell Schulz. (Creative Commons 3.0 License)

What fascinated me about McQueen’s work was his desire to reimagine fashion at the very limit where humanity met the animal kingdom. Walking amidst those bizarre mannequins, I was not surprised to read later on that he took inspiration from the silhouette of birds taking flight. For him, the human desire to be clothed was a basic instinct and that made him look to the animal kingdom in search of the energy that he wished to portray. I remember taking the phone out and writing a quick note to myself: “Possible protagonist: fashion designer who finds inspiration in the animal kingdom.” There lies one the roots of the character of Giovanna Luxembourg, the fashion designer in Natural History whose animal-centric project sets the novel in motion.

Photo of the Savage Beauty Exhibition at the Met, 2011. Photo Credit: Wesley Chau. (Creative Commons 3.0 License)

At some point in the following years, I began to realize that what had intrigued me from the exhibition was tied to an image that had always captivated me since childhood. I remembered that growing up, my brother and I would often find in our backyard in Costa Rica a small animal which we called Juan Palo: a branch-looking insect that often adopted the brownish colour of wood in order to hide between the trees. Like the chameleon or the praying mantis, it mimetically took the shape and colour of its surroundings in order to avoid its predators. I began to think that what McQueen had understood was our basic animal instinct of imitation, survival and dissemblance. I began to research animal mimicry and that’s how I first heard about the life and works of Abbott Handerson Thayer.

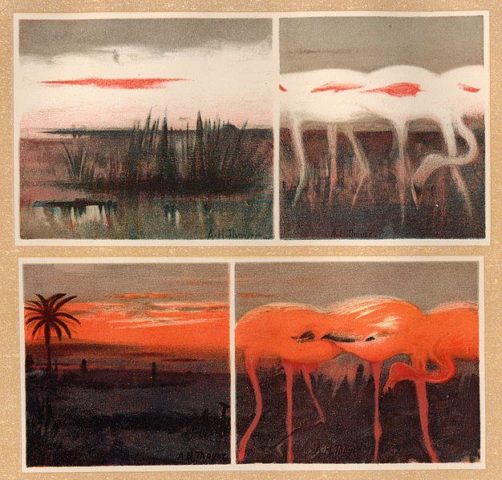

Abbott Handerson Thayer, White Flamingoes, Red Flamingoes, The Skies they Simulate. 1909. (Creative Commons 3.0 License)

Born half-way through the nineteenth century, Abbott Handerson Thayer grew up in Boston and quickly found in painting a way of expressing his fascination with the animal world. What drew me to this figure, however, was something else. Towards the 1890’s Thayer had begun constructing a theory regarding the role of countershading in nature. His ideas, which were to be developed in the 1909 book Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom, were soon to provide the grounds for the new theories of camouflage that were emerging in the wake of the First World War. Somehow, I told myself, he was not far from the world of McQueen’s savage beauty.

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Counter-shading, study folder for book Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom. © Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of the heirs of Abbott Handerson Thayer.

“The only things that appear are those which are first able to dissimulate themselves,” I would read months later in an essay by Georges Didi-Huberman. In a way, I began exploring Thayer’s life and his theories as a way of explaining this interplay between visibility and invisibility. A game of imitation that for me sat close to the very heart of what we do as artists, as writers, as photographers, as painters.

Abbott Handerson Thayer, A photograph of a model duck, 1908. (Creative Commons 3.0 License)

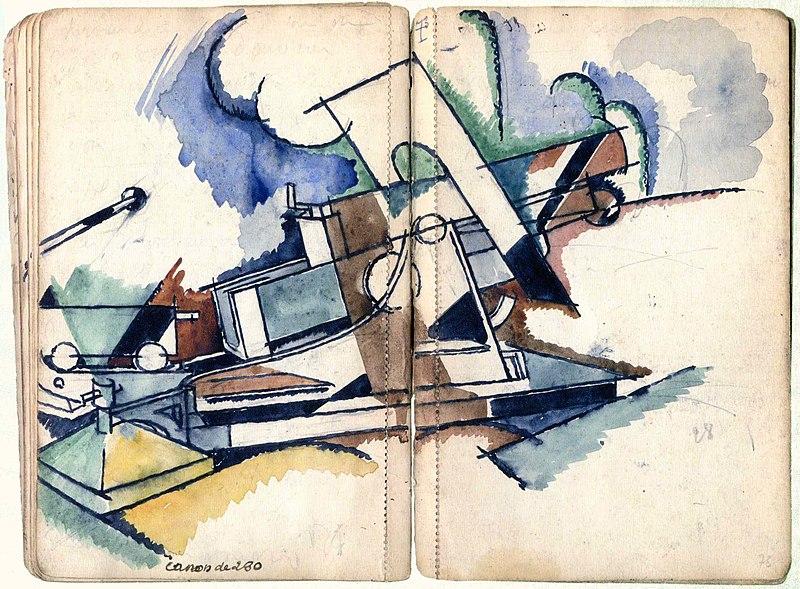

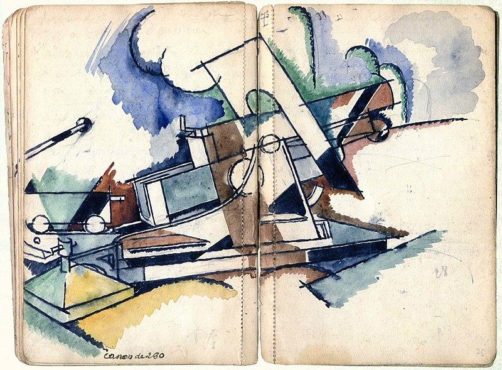

What Thayer had begun to sketch was the knot between art, politics, and nature that would soon become evident with the rise of camouflage. He would famously take his ideas to Winston Churchill, but his attempts at convincing the British statesman would prove unsuccessful. Others, however, would have better luck. At the outset of the First World War a group of artists baptized as the camoufleurs, composed mostly by Cubists, would emerge as true artists of war. André Mare’s ink and watercolour sketch The Camouflaged 280 Gun is a perfect example.

André Mare, Cubist-type sketch in black ink of a 280 calibre first World War field gun. (Creative Commons 3.0 License)

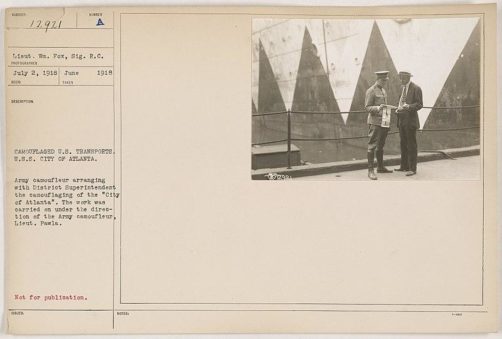

Gertrude Stein would later remember how, seeing a camouflaged tank traverse the streets of Paris, Picasso exclaimed: “Yes, it is we who made it, this is Cubism.” The phenomenon of the camoufleurs, which Kurt Vonnegut would explore in his 1987 novel Bluebeard, outlined the complex relations between art, politics and nature, in a world where nature was slowly being destroyed.

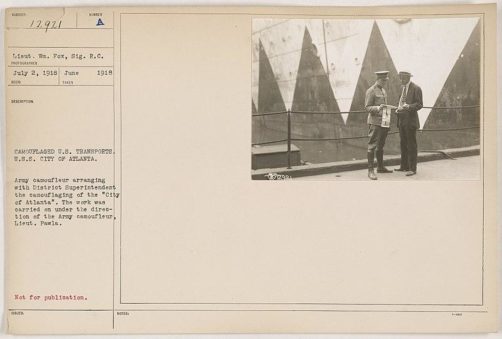

111-SC-1292, Photo Credit: War Department. Army War College. (Creative Commons 3.0 License)

Camouflage, like animal mimicry, makes identity shake. It shows that at its core, identity is nothing more than a game of imitation and dissemblance. Every identity is nothing but a mask, as one of Latin America’s iconic revolutionary leader – Subcomandante Marcos – would later say from the depths of the Lacandon Jungle in Chiapas. His famous ski mask is a call for questioning the contemporary invisibility of indigenous communities, turning the politics of camouflage into a site of political resistance.

Subcomandante Marcos in Chiapas, México 1996. Photo Credit: José Villa. (Creative Commons 3.0 License)

Early in February 1995, one year after the emergence of Marcos and the Zapatista movement, the Mexican government tried to remove his mystique by publically unmasking him. The strategy backfired: four days later thousands of people marched wearing ski masks and shouting: We are all Marcos! The logic of concealment devised by Marcos foreshadowed the viral logic of simultaneous anonymity and ubiquity that contemporary politics would soon take in the age of social media.

Alexander McQueen dress from his last show, 2011. Photo credit: John W. Schulze. (Creative Commons 3.0 License)

In a way Natural History traces that impossible journey which leads from the Savage Beauty exhibition of Alexander McQueen to the political revolution of Subcomandante Marcos: from the runways of Milan to the Lacandon Jungle.

Carlos Fonseca was born in San José, Costa Rica, and spent half of his childhood and adolescence in Puerto Rico. In 2016, he was named one of the twenty best Latin American writers born in the 1980s at the Guadalajara Book Fair, and in 2017 he was included in the Bogotá39 list of the best Latin American writers under forty. He is the author of the novel Colonel Lágrimas, and in 2018, he won the National Prize for Literature in Costa Rica for his book of essays, La lucidez del miope. He teaches at Trinity College, Cambridge, and lives in London.