The only work James Harvey completed in the last year of his life (he died, this past May, at the age of 90) was a six page introduction to his late friend Gilberto Perez’ book The Eloquent Screen. And the writing of that short piece was, he often admitted to me, torture. The torture arose not simply from the perfectionism and occasional bouts with depression that often slowed his writing. (Not to mention the difficult task of writing about a dead friend.) There was something else. As much as Jim admired his friend’s work, Perez had described his book as being about “the rhetoric of film”. Hearing those words, Jim confessed, “my heart sank a little.”

The introduction he finally managed to write turned out superbly, of course, full of love and respect for his friend. But there was no hiding the fact that film rhetoric and theory were the last things Jim cared about. In his three brilliant books about the movies (Romantic Comedy in Hollywood, Movie Love in the 50s and Watching Them Be, published over the course of 27 years), he proved himself to be the film world’s great anti-theorist. Writing about the movies was, for him, rooted not in academic analysis but in the experience of watching them, preferably as a member of a large audience (“those great impersonal audiences”, as he wrote about the crowds he first witnessed in the movie palaces of his childhood), popcorn or, as was later the case, espresso in hand. The moviegoing experience was, for him, a “great democratic event” that allowed the viewer to feel, from an early age, “part of the mass reality” around him . Thus, in writing about Garbo, he found it essential to tell you not just how but where he had been first exposed to her: in 1955, in “a crowded theater in Chicago’s Loop”, when MGM rereleased Camille “with all the fanfare of a first run movie”. The “fanfare” was never a thing to be dismissed; neither were the box office receipts. They were all part of the experience of watching, and caring deeply about, movies, and Jim’s writing was never funnier than when he described the “pandemonium” of being part of a college crowd in Ann Arbor, throwing catcalls at the screen during a showing of the Mitzi Gaynor musical The I Don’t Care Girl. Moviegoing, as Jim would be the first to admit, wasn’t always sublime, but then, it didn’t need to be. If you opened yourself to it, it became an enduring part of one’s life, as deep, and as defining, as the experience of love.

Jim would blanch and get up from the table if I ever suggested he was a kind of sociologist (he’d have much preferred the phrase “cultural historian”), but there was a deep impulse in his writing about movies that needed to locate them and tell us what they had meant to audiences in their own time, to make us feel—often rapturously—what it must have been like to watch a 50’s movie in the 50’s. Great tomes have been written to explain and encapsulate that decade, but I think I’ve learned more about “the falsity and underlying desperation of American bourgeois life” in that era just by reading Jim’s six page exegesis of Nicholas Ray’s Bigger Than Life (a movie about a modest suburban high school teacher who becomes addicted to cortisone). His masterpiece in this vein is his chapter on Psycho in Movie Love in the 50’s. Anyone who hasn’t watched that movie recently is likely to remember only those three or four shocking scenes that have haunted our collective memory for decades. It was Jim’s genius to concentrate instead on the movie’s much less sensational first half, to analyze carefully and deeply, the “strange sort of love scene” (Janet Leigh’s words) between “Norman” and “Marion”, after Norman has fixed her a little something to eat. It was Janet Leigh’s 50’s “normalcy” (“She inevitably reminds you of that very popular girl in high school you could never get a date with”) that sets us up for the horror to come. And it was the particular quality of Jim’s watching that allows him to show us the ways Hitchcock himself, like Norman Bates, set himself at a prohibitive distance from that alluring but (for most of us) unreachable state of “at- homeness in the world” that Janet Leigh so effortlessly embodied. No other writer has, to my mind, articulated so well just what Norman Bates, and with him, Hitchcock, was slashing out at in that shower scene.

Little of this would matter, or it wouldn’t matter in the same way, if Jim hadn’t been a brilliant writer as well. Certain phrases of his live in my mind years after my first reading them. Fred MacMurray’s “curdled boyishness”, the “ruined handsomeness” of Robert Forster (in Jackie Brown), his description of Garbo, after she’s been repudiated by a callow lover, looking like “the most grown up person in the world”. No one could see and fully notice as much without willingly ceding huge tracts of himself to the kind of consuming love Jim found at the movies. Which is part of what made him such an elusive friend, such a delightful but finally unknowable man. Over the course of a friendship lasting two decades (begun after I had written him a fan letter), I was never able to probe very deeply into his personal life- beyond, that is, his Catholic upbringing, his difficult childhood in Chicago. And not for want of trying. I gather I was not alone. (“It was our movie life that mattered to us as friends,” he wrote about Gil Perez. “That for us was the personal one.”) And so it was. Dinners with him could be raucous, hilarious, exhausting. (He often walked from his apartment in Carroll Gardens in Brooklyn to meet me at a restaurant in lower Manhattan, and ended the evening less exhausted than me, his decades-younger companion.) They were dinners that often spilled over to adjoining tables, but the subject, the deeply personal subject, was always the movies. I recall one of our last dinners, where he discovered that our server had never seen a Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers movie. He spent the bulk of the evening convincing her, to her apparent delight, that she was in for the treat of her life.

If you knew this deeply eccentric man well, you discovered that if there was any subject he cared about as much as the movies (or nearly as much as the movies) it was animals. For years, he lived with a stray cat he had picked up, one he claimed he didn’t even like, one who would often attack him without warning, but whom he could not bear to give up. There were moments when his two passions mixed in a way that I imagine must have been blissful. He once described to me sitting in a darkened Manhattan theater, the only audience member in the room, weeping over a documentary about- well, I believe it was a documentary about a whale. And then there’s the final essay in Watching Them Be, detailing his besotted relationship to Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar– “probably the greatest movie I’ve ever seen”. It was up to others to load the non-human title character with deeper meanings. For Jim, that was overkill . “Balthazar… is not a virtual human being. Nor is he Christ, as many critics have read him- nor is he all of us or Everyman. He is what you see- a donkey.” And that, for this most spiritually alert of men, was quite enough.

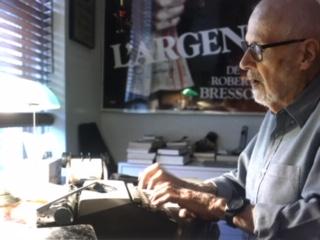

In his last years, when he wasn’t struggling over that introduction he’d been asked to write, Jim worked on a proposal for what he supposed would be his final book. That “supposed” has to go in quotes. Such was his optimism that, having taken fourteen years on each of his last two books, he assumed he had plenty of time to do this one. His proposed title was “Moviehood: An American Life at the Movies”. It was to be “ a mix of criticism, personal memoir, and cultural history”. Nearly a third of the ten page proposal consists of him relating how, as a boy, he followed the first run showings of Fantasia, in the ‘40’s, from Chicago theater to Chicago theater, chasing it down wherever it happened to be playing, like a boy chasing after his first love. Late at night, in the last years of his life, my phone would ring, at 10:30, 11, just when my eyelids were drooping. It was my night owl friend, wanting to talk. Was the proposal good enough? Should he send it in? Yes, of course, yes. But he never did, holding back out of perfectionism, or fear of rejection, or something else, something he could never find a way to fully relate. “That which is beautiful in a film is the movement toward the unknown”, he quoted Bresson as having said. So it is with friendship, too.

Anthony Giardina is the author of four previous novels, most recently Norumbega Park, and one collection of stories. His short fiction and essays have appeared in Harper’s Magazine, Esquire, GQ, and The New York Times Magazine, and his plays have been widely produced. He is a regular visiting professor at the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas, Austin. Giardina lives in Northampton, Massachusetts.

James Harvey was a playwright, essayist, and critic, and the author of several books on the movies, including Movie Love in the Fifties and Romantic Comedy in Hollywood. His most recent work appeared in The New York Review of Books and The Threepenny Review. He was a professor emeritus at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, where he taught literature and film, and he had previously taught film at the University of California at Berkeley, the New School, and Sarah Lawrence College. He lived in Brooklyn, New York.