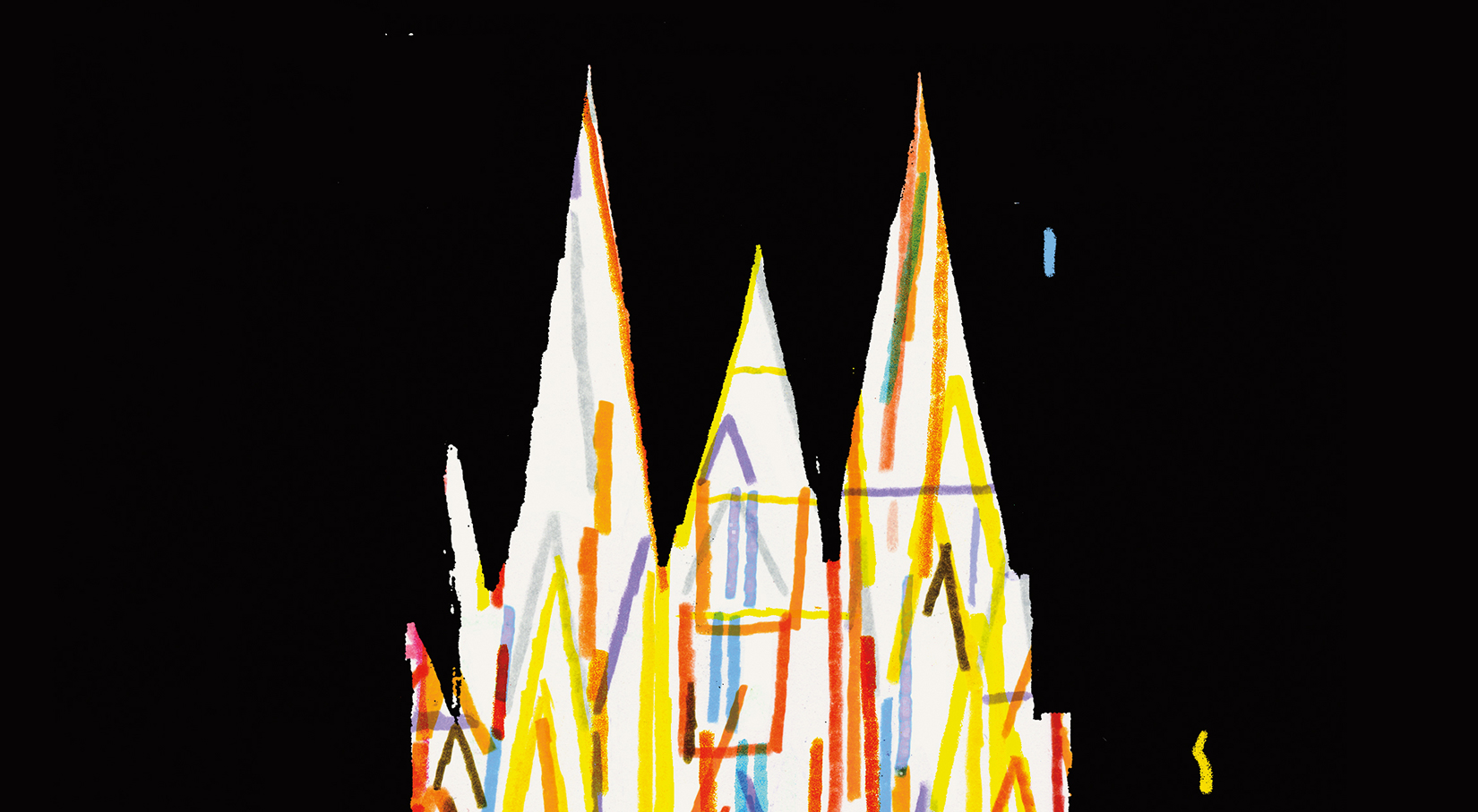

The Stuart family moves to a marginal neighborhood of Cienfuegos, a city on the southern coast of Cuba. Arturo Stuart, a charismatic, visionary preacher, discovers soon after arriving that God has given him a mission: to build a temple that surpasses any before seen in Cuba. In a neighborhood that roils with passions and conflicts, at the foot of a cathedral that rises higher day by day, there grows a generation marked by violence, cruelty, and extreme selfishness. This generation will carry these traits beyond the borders of the neighborhood, the city, and the country, unable to escape the shadow of the unfinished cathedral. Told by a chorus of narrators—including gossips, gangsters, a ghost, and a serial killer—who flirt, lie, argue, and finish one another’s stories, Marcial Gala’s The Black Cathedral is a portrait of what remains when dreams of utopia have withered away.

ROGELIO

“Ornament is crime,” a great architect said, and that was my premise, I wanted the building to be perfect in its almost necessary simplicity, I wanted all of its complexity to come from the harmony and the quality of the materials used, I wanted to bring a piece of modernity to a sleepy Cuban town, I wanted that filthy neighborhood of Punta Gotica to have at least one thing to show the world, and I made an effort to achieve this.

“We had something else in mind, I don’t know, something more traditional,” Basulto said to me, and showed me a picture of the Church of the Holy Sacrament in Oklahoma, where the officiant was the Reverend James Harrison Fitzgerald, the corpulent black pastor who had done so much to collect the money we needed to build.

I hadn’t slept all night and was somewhat irritable.

“If I have to redraft this, it’s over, find another architect.”

“It’s not that we don’t like it,” Arturo Stuart said. “It’s that it’s so different, and it looks very expensive. Besides, where are you going to find the workers to do something like this? In Cuba, there aren’t builders who do this kind of work anymore, the mosaics alone would be a headache.”

“The materials and the workmen will appear.”

“Yes, but at what cost?” Basulto said. “We only have twenty thousand dollars, and money doesn’t grow on trees.”

“Is this the entrance?” Stuart pointed at something on the architectural plan laid out on the table.

“You can access the temple’s interior many ways. The concept is accessibility, permission, the temple is like an open hand everyone can hold . . . Perhaps you can see it better on the perspective drawing,” I said, “but I didn’t have time to finish it.”

The concept is accessibility, permission, the temple is like an open hand everyone can hold

“So do it,” Stuart said. “Do it and bring it over, and then we’ll talk.”

GRINGO

Knock, knock, they banged on the door, and I knew it was the police. I opened up and there they were: a fat mulato with a checked shirt and the sector chief.

“Blessings,” I said to them, and smiled widely. “Come in and sit down.”

They sat on the sofa and I took a seat facing them, in one of the armchairs.

“You’re really thriving, Ricardo Mora Gutiérrez,” the sector chief said. “This looks like a showroom, you’re living better than Rockefeller. Don’t tell me you started working, because all you’re good for is construction and that doesn’t pay much. What are you involved with, Ricardo Mora, huh?”

“Nothing. I converted, now I follow the path of the Lord.”

“Really? How nice. How long ago did that conversion happen?”

“Nine months ago.”

“Nine months? Sounds like a pregnancy,” the sector chief said, and let out a tiny laugh like a sad hyena.

“In a way, it is, God is something that fills you.”

“Gringo the Christian, well, well, this is something you wouldn’t see anywhere else.”

“Now you know. Would you like coffee?”

“Why not? Bring a cup for each of us, but don’t you spit in it.”

“I wouldn’t dare.” I went to brew the coffee.

When I returned, the sector chief asked me how much the living room set had cost me.

“I got it cheap, five hundred.”

“That’s a steal. Who makes it? So I can buy myself one, give me the telephone number or the address.”

“That’s in dollars.”

“Well then, you should have started there. That’s a lot of money. I’ve never seen that much all together and, you know, I work hard . . . Where’d you get it from, Gringuito? Don’t tell me you won the lottery.”

“My brother sent me the money.”

“Damn, your brother’s a really nice guy.”

“Now you know.”

“And here I was, thinking he left and never wrote to you again.”

“He decided it’s never too late to go to school. He got a degree as a nurse and works at one of the best hospitals in Miami, and he’s decided to help me.”

“What a brother, he’s pure gold.”

“We were always very close.”

“You don’t need to say so, you used to kill cows together.”

“If you say so . . . Excuse me, the coffee’s almost ready.”

“How do you know?”

“I can smell it.” “With a nose like that, you should become a policeman, Gringuito . . . But go, I don’t want your coffeemaker to blow up . . .”

“So delicious,” the sector chief said later, when he sipped his coffee. “You must be asking yourself what we’re doing here at your house. Right?”

“Of course.”

“You can’t think of anything?”

“I’m not psychic.”

“Ah, you’re not psychic . . . Well then, I’m going to help you. We’re looking for an individual, from Santiespíritu, folks say they saw him with you.”

“With me?”

BERTA

On February 27, 2007, the ghost started to torment me. The first time I saw him, seated at the entrance to la cuartería, he was looking ahead in concentration, as if he were waiting for something. I knew he was dead because his eyes were rolled back and he was naked. It was nearly six in the evening, the time when kids are playing soccer and the street is full of adults coming back from work or going to their businesses. No one noticed. Only I saw him and his strong body; he had a scorpion tattooed on his right shoulder and a snake around his belly button, he was tall and would have been handsome without the open wound crossing his neck from one end to the other. He pointed at the wound with the index finger of his right hand and his eyes full of tears. I started to run.

I didn’t eat that day.

“A naked dead man appeared to me,” I told my mother.

“You and your jokes.”

“I’m serious.”

“So tell him to come cook for us, you don’t know how to do anything and I’m pretty tired of the stink of grease.”

Don’t run, my name is Aramís and I’m from Cabaiguán, he said to me the second time I saw him, on a steamy Tuesday. I was at school and had asked the chemistry teacher for permission to go to the bathroom. I’d just sat down on the toilet when he appeared and said that. All I could do was look at him and say, You don’t exist, then I closed my eyes, and when I opened them, he was no longer there. When I returned to the classroom, I was so pale, I looked like Michael Jackson.

“I was going to send someone for you,” the teacher said. “I thought you’d gone down the toilet.”

“I don’t feel good. I saw a dead person.”

“You can tell,” he said with a smile, but then he let me leave.

I went home, made the most of my mom’s not being there, took two diazepam, swallowed them, sat on one of the rocking chairs in the living room, and rocked until the pills began to take effect; then, when I couldn’t keep my eyes open, I went to lie down and in my bed was the dead man.

“My name is Aramís and I’m from Cabaiguán. I came to Cienfuegos looking for a motorcycle because I wanted to surprise Araceli, who wanted to see me on a motorcycle, but as you can see, they killed me and I can’t figure out how to return to my town and tell them I’m dead; I went to the station but I can’t get on a bus; when I try boarding, the bus turns to smoke and I find myself again in the house where they did this to me.”

I can’t figure out how to return to my town and tell them I’m dead; I went to the station but I can’t get on a bus; when I try boarding, the bus turns to smoke and I find myself again in the house where they did this to me.

The dead man took his hand to his throat and then implored:

“Help me.”

IBRAHIM

In spite of everything, those days were good; my wife would make my coffee; after drinking it, I would grab my bicycle and go to the temple. No matter how early it was, brother Arturo would already be there doing something: organizing the work tools or tidying up. We would pray together and await the arrival of our other brothers in Christ, the architect and the bricklayers, in order to have breakfast and begin the day’s tasks. Ibrahim is a Syrian name, and everyone has always referred to me as the Arab, even though I don’t have people in the Islamic lands: I was named Ibrahim after a telenovela that my mother saw years ago.

“Don’t you sleep, maestro?” I once asked.

Stuart looked at me with those deep eyes of his that, in spite of everything, I dare to call those of a prophet, and said, “Árabe, when the church is done, I’ll sleep so much that everyone in my house will think I’ve died.”

To raise a temple up where there was nothing but weeds, to see it grow, take shape, go from being four stakes in the ground to a building whose walls rise each day . . .

At the beginning, they mocked us, and even though we had all the necessary permits possible, the police and inspectors came to harass us. When we were in full swing, they called the architect and told him we had to stop and look for all the receipts proving we’d acquired the cement through official means and not illegally. Then Rogelio had to bike to his house to look for the receipts and show them, otherwise we couldn’t continue. Another day, they’d ask about bricks, the paint, about whatever they could, and there were many inspectors, so they took turns. One of the ones who fought with us most was a short little lady, chubby, who always wore a handkerchief on her head. She would arrive on a motor scooter like Gringo’s, stand close to everything, open a black folder, pull out a planner, and start taking notes with her eyes fixed on us. She tried to make us nervous, but she couldn’t anymore because the spirit of the Lord was with us. We sang hymns to Christ as we worked. Especially the one that says, “Christ has risen.” Many of the neighbors accompanied us, and some of them worked with us, although we had to take many precautions because as soon as you let your guard down, they could take one of your work tools, a can of paint, half a bag of cement, whatever, all to resell it for moonshine.

GRINGO

“Yes, with you . . . I’m going to refresh your memory: he was alone, white, tall, strong, about twenty-five years old.”

“Ah, that one . . . That guy left the country, a speedboat came to get him.”

“How do you know?”

“He told me so. ‘I’m leaving,’ he said, ‘and you won’t see any trace of me again.’”

“Oh, yeah? So what did he go see you for?”

“He was looking for my brother’s address, since they knew each other from when my bróder lived in Cabaiguán, and he wanted to meet up with him in Miami.”

“So did you give it to him?”

“Of course I didn’t, my brother has enough problems already without having to take care of some dumbass from Santiespíritu.”

Both guys looked at me for a few seconds without saying anything, then the mulato said, “He’s lying. Aramís would never leave the country, he was a hardworking, well-integrated young man, from a family with an impeccable record. I very much doubt that he would have known the brother from here. Besides, what person, living close to the northern coast, would think of coming down to Cienfuegos to leave Cuba?”

“I said the same thing to him. ‘Brother,’ I said, ‘isn’t it better for you to leave through Sagua la Grande, just a quick hop from Miami?’ And he said that it was bad up there, the border guards were on high alert and the trip cost twice as much.”

“He told his family he was going to Cienfuegos to buy a motorcycle.”

“That was his story, but really, he was taking off.”

“And he came and told you when you’d barely met?”

“Now you know.”

“How strange,” the mulato said.

“Not just strange, superstrange,” said the other one. “There’s something fishy here. So where were you and Aramís going when you were seen?”

“Over to see some chicks. He was a fan of the mulatas.”

“Chicks? What chicks? Name and address.”

“I would give it to you, but one of them is married.”

“Well, well, out looking for chicks . . . Didn’t you just tell me that you were Christian?”

“So Christians don’t fuck?”

“Of course they do, Gringuito, of course they do . . . Okay, so you saw the chicks, and then?”

“He went on his way and I went mine.”

“And which way did he go?”

“That, I can’t tell you.”

“Why not?”

“Because I don’t know.”

“You never know anything.”

IBRAHIM

He was a good speaker, if you ask me, he was a better preacher than the pastor, and he had such a good memory that he could cite all the Scripture without making a mistake, and that was at just shy of fifteen years old. But something was off about him, something bad, he was proud, he thought he was predestined for something big, and that made him difficult to deal with, he barely collaborated on building the temple. His brother, just a year older, did work like an ox even though his father was merciless with him, he treated him as if he hated him, as if the kid should pay daily for not being perfect. I didn’t like that and one day I told him so. We were placing the fourth row of bricks. David King, who was working as an assistant of mine, dropped one of those bricks, which only broke in one corner, and his father became so furious that he practically went mad:

“Do you know how much those bricks cost?” he yelled.

“No, papá.”

“So then be more careful.”

“Yes, papá.”

“It could happen to anyone,” I said.

He was like that, calm on the surface but with a barely contained rage ready to come out at any moment.

“When I want your opinion, I’ll ask for it,” old Stuart said to me, and got in my face, it was as if he were going to hit me there in front of everyone. He was like that, calm on the surface but with a barely contained rage ready to come out at any moment.

GRINGO

I wanted to bring her with me, even if I had to pay twice as much for the boat trip. I’ll get the money back, I thought, and sometimes I think of how different my life would have been if Johannes had said to me, I’m going with you, when I proposed it to her, maybe I wouldn’t be here waiting to meet my maker, maybe I would have blended in and become one of those guys who put little American flags on the hoods of their cars and grill on Sunday afternoons, and later there they are, all fat, beer in hand, arguing with the neighbors about the World Series. If I had taken Johannes with me, everything would have been different, I’m sure, I wouldn’t have gotten myself in a mess; maybe I would have done well, because to get ahead here, you don’t have to bump anyone off, what you need here above anything else is someone to love you, and, ah, someone you can love, which is even harder. If that afternoon, when she was coming back from her school weighed down with poster board and paintbrushes, Johannes had played along when I said to her, “Let’s go sit down in Martí Park, we have to talk,” and then once we were there and I asked if she wanted a beer, since I had so much to tell her, if at that moment she had said, Yes, bring me a beer, and if she had smiled at me, my life would be different now, I’m sure of it, but that Johannes said no to the beer, and later, no matter how much I talked to her, she kept refusing:

“No, Ricardo, I’m not abandoning my future for you, or for anyone.”

“What future do you have in this shitty country? Besides, I love you, do you know that? Because of you, I changed and now I’m someone else.”

“I only like you as a friend, Ricardo, I’ve tried so many ways to make you understand. That’s how things are and they can’t be changed, I’m sorry.”

That’s how these bitches are, women, they’re always sorry, they rip your heart out and then they’re sorry, simple as that. I don’t trust any of them anymore. I don’t even trust my mother, that’s the truth. The other day, a ghost appeared to me, it came from Cuba, to ask me why I had killed him when he was in the prime of his life.

“That’s how it is, you go around doing as much damage as you can until it’s your turn for the coffin to drop, and you know, my time has come, I have just days left, so don’t worry, soon you’ll be happier; but when I’m dead, I don’t ever want to see you; if I see you there on the other side, I’m going to give you the kind of beating that everyone but you will enjoy.”

That’s what I said to him, because you have to talk to them, to ghosts, forcefully, to put them in their place.

I could have also brought Piggy, so he could have at least been my secretary, not left him all messed up like I did, thinking that Piggy wouldn’t adjust here, when in reality, the one who didn’t adjust was me. I would have brought him with me if, after all, I’d known that the trip would turn out to be free, I had my Makarov for a reason.

Later, Johannes said to me, because they wait until the end to drop the last bomb, that’s how they are, women:

“I’m never going to love you, Ricardo, because you’re a bad man, I know it, bad. You may fool my father, but you don’t fool me, you are a bad man.”

“Can’t I have changed?”

“I don’t think so.” She stood up. “Goodbye.”

Then she looked directly into my eyes, very seriously, and offered me her hand. I wanted an abyss to open up and the earth to swallow me at that moment, but those things never happen, at least not that quickly, so I shook her hand and asked if I couldn’t hold on to the least hope, and why was she saying I was a bad guy when I was just fighting to get ahead like everyone else?

“What you did to Ingrid was very bad.”

“Ingrid who?”

“You know very well who, that white chick who studies dance. You got her pregnant and didn’t go with her when she got an abortion, you can’t just do that to people.”

That bullshit? I thought. Johannes was so naïve.

Marcial Gala was born in Havana in 1963. He is a novelist, a poet, and an architect and is a member of UNEAL, the National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba. He won the Pinos Nuevos Prize for best short story in 1999. The Black Cathedral received the Alejo Carpentier Award for best novel in 2012 and the Critics’ Award in 2012. He lives in Buenos Aires and Cienfuegos.

The daughter of Cuban exiles, Anna Kushner was born in Philadelphia and has been traveling to Cuba since 1999. She has translated the novels of Norberto Fuentes, Leonardo Padura, Guillermo Rosales, and Gonçalo M. Tavares, as well as two collections of non-fiction by Mario Vargas Llosa.