In his recent New York Times op-ed, Martin Scorsese argues that in order for a movie to be more than mere entertainment—for it to be cinema—it requires “the unifying vision of an individual artist.” Most contemporary movies lack this element, Scorsese says, because the companies and conglomerates that finance films today are averse to risk, and thereby inimical to artists, since “the individual artist is the riskiest factor of all.”

On this point, Scorsese is entirely correct. Indeed, he’s written as neat a summary of Hollywood as one is likely to find. Scorsese goes wrong, however, when he claims that this is a recent change in moviemaking—something that’s occurred “in the past 20 years,” as well as “stealthily and under cover of night.” Here, nothing could be farther from the truth.

Hollywood has never been in the business of making art; rather, Hollywood has always been in the business of making commercial entertainment. To that end, nearly everyone involved in “the industry” has always sought to minimize risk. Movies, after all, are expensive endeavors, with even the cheapest movies costing hundreds of thousands of dollars. There’s a reason why Hollywood movies are almost all stories in popular genres featuring proven stars: genre and stars are two time-proven ways of compelling folks to buy tickets.

But even though Hollywood studios don’t set out to produce art, that doesn’t stop their movies from being works of art; far from it. That’s because while Hollywood isn’t in the business of making art, it also isn’t in the business of not making art. Rather, Hollywood is ambivalent to whether the movies it makes are artworks. If the movie is a work of art and it sells, then that’s great! So much the better! And if it’s not a work of art and it sells, that’s fine, too! All that matters, as far as the studios are concerned, is that the movie sells. Which is why it’s always been possible, then and now, for artists like Martin Scorsese to make commercial entertainments that are also works of art—“cinema.” While artists aren’t privileged by the system, they are able to take advantage of it, provided the artworks they make also make some money.

Artists, just like everyone else in Hollywood, must be sensitive to the market, which is always changing, and changing with it the movies that get made.

To that end, artists, just like everyone else in Hollywood, must be sensitive to the market, which is always changing, and changing with it the movies that get made. The advent of television, for instance, led film studios to make widescreen, Technicolor films, since people couldn’t see those films at home on their TV sets. And when those big, expensive widescreen productions started flopping because they didn’t appeal to teenage Baby Boomers, studios switched to financing smaller films about rebellious youngsters—Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Easy Rider. The old-timers in charge of the studios in the late 1960s didn’t care for those “hippie pictures,” but they did like the money they made. And when that market petered out, as the Baby Boomers grew up and settled down and moved to the suburbs, artists like Martin Scorsese transitioned from making films like Mean Streets, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, and Taxi Driver to Goodfellas, Cape Fear, and Casino.

The past twenty years have seen their own changes in the market. Genre and stars are no longer the guarantors of ticket sales they once were, even as the costs of making and advertising movies have steadily risen. (For more on why this is, see film scholar Kristin Thompson’s excellent book The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood.) Audiences have also spent the past two decades fragmenting and fracturing, awash in entertainment options, from podcasts to video games to prestige TV series to social media. Today, it’s easier than ever to skip a new movie in the theaters, opting to wait to stream it at home. Martin Scorsese’s latest film, The Irishman, was financed by Netflix, which gave it only a cursory theatrical release in major cities before making it available to subscribers the day before Thanksgiving.

To combat these structural changes, Hollywood has increasingly turned to making franchises—not just a single movie, which might flop, but whole suites of products, from sequels to spin-offs to theme parks to all manner of merchandising. Transformers may have started out as a line of children’s toys advertised by a cartoon, but today it’s much more than that: movies, roller coasters, T-shirts, car decals, bags of cookies—you name it. Fans of franchises turn out for multiple films and buy lots of merch, as well as make loyal brand ambassadors, working (for free!) to turn others on to the brand.

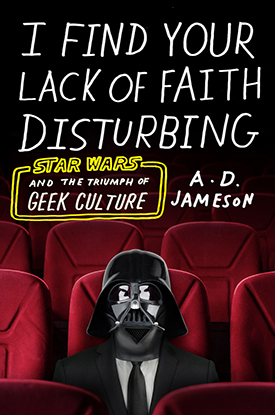

As it happens, this trend toward franchises has coincided with the rise of the Information Economy, and with it, the triumph of geek culture (which I describe in detail in my most recent book). Back in the 1990s, when I went to college, my parents encouraged me to major in STEM—short for Science, Technology, Engineering, Math. I wound up getting my PhD in English, but the undergrads I now teach are smarter than me, financially speaking, and mostly majoring in STEM. At the same time, information technology has spread, becoming an essential component of our lives, to the point where we all carry with us miniature computers that keep us glued to the internet. The proliferation of cell phones and laptops and tablets, the proliferation of Information Technology and STEM, has made all of us—including the Baby Boomers—geekier. That’s why our fantasy heroes have switched from being Peter Fonda’s Captain America, in Easy Rider, to—well, Captain America himself, who pals around with the high-tech Avengers.

The Marvel films, more than anything else, sell a technocratic fantasy, a world where geeks get to be in charge. Captain America is a ninety-pound weakling transformed into a super soldier by a scientist’s serum. He joins the Avengers, whose leader, Tony Stark, isn’t a goober, but (in his own words) “a genius, billionaire, playboy, philanthropist.” He’s a rock star, just like all of the Avengers. Even the hunkiest one in the bunch, Thor, hails from a society that’s technologically superior to ours, and flies around in Quinjets and Helicarriers, battling evil robots. Henry Hill, the complex protagonist of Goodfellas, always wanted to be a gangster because he couldn’t stand the thought of living a normal, quiet life. Neither can the Avengers, and today more people want to fantasize about being Iron Man than they do a Mafia gangster, or a hippie dropping acid in a graveyard in New Orleans. That’s the market.

Viewed from this perspective, Scorsese’s complaint doesn’t really have anything to do with superhero movies. The big studios happen to be making geeky films because people will currently pay to see them. But so what? The big studios are always making something, and some set of people somewhere is always complaining that it isn’t what they want to see. I’m old enough to remember how, back in the 1980s and early ’90s, critics complained about Hollywood action movies, which were supposedly rotting our brains. Most of those movies were indeed junk—fun junk, but junk—but somehow we still got great works of art like Die Hard, Predator, and Speed. Before that, people complained about Westerns and gangster films, which they derided as kiddy-centric, formulaic, violent, mindless. But a thing of beauty is a joy forever, and the great Westerns and the great gangster films have endured, while lesser movies have faded away.

Clever artists have always found ways to make daring artworks inside a system committed to making risk-free entertainments.

As for whether the Marvel movies, and other superhero films being made today, are artworks—yes, some of them are, even as most of them are not. In that regard, nothing has changed. Clever artists have always found ways to make daring artworks inside a system committed to making risk-free entertainments. Back in the late 1950s, Ernest Lehman and Alfred Hitchcock conspired to make the ultimate Alfred Hitchcock movie. The result was the consummate masterpiece North by Northwest. Fifty years later, Drew Pearce and Shane Black conspired to make the ultimate Shane Black movie. The result was Iron Man 3, which is the work of an auteur, replete with Black’s trademark preoccupations. It merrily dances its way around genre clichés, leaving other superhero flicks in the dust. In this way, it stands alongside Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight films and James Mangold’s Logan, which are bold, authorial films, unified by the visions of their artists. The Hollywood powers that be are always cranking out entertaining films to satisfy the market. But somehow, artists—real artists—keep finding ways to make works of art.

A. D. Jameson is the author of several books, most recently I Find Your Lack of Faith Disturbing: Star Wars and the Triumph of Geek Culture, and Cinemaps, a collaboration with the artist Andrew DeGraff. His fiction has appeared in Conjunctions, Denver Quarterly, Numéro Cinq, and elsewhere. In May 2018, he received his Ph.D. in English from the University of Illinois at Chicago.