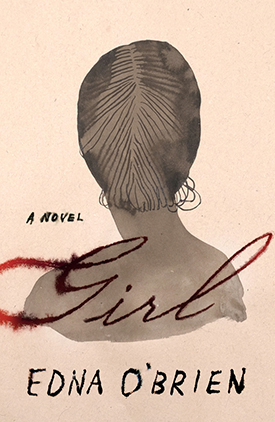

In Girl, Edna O’Brien presents a harrowing portrayal of the young women abducted by Boko Haram. Set in the deep countryside of northeast Nigeria, this is a brutal story of incarceration, horror, and hunger; a hair-raising escape into the manifold terrors of the forest; and a descent into the labyrinthine bureaucracy and hostility awaiting a victim who returns home with a child blighted by enemy blood. From one of the century’s greatest living authors, Girl is an unforgettable story of one victim’s astonishing survival, and her unflinching faith in the redemption of the human heart.

I was a girl once, but not any more. I smell. Blood dried and crusted all over me, and my wrapper in shreds. My insides, a morass. Hurtled through this forest that I saw, that first awful night, when I and my friends were snatched from the school.

The sudden pah-pah of gunshot in our dormitory and men, their faces covered, eyes glaring, saying they are the military come to protect us, as there is an insurrection in the town. We are afraid, but we believe them. Girls staggered out of bed and others came in from the veranda, where they had been sleeping because it was a warm, clammy night.

The moment we heard

They could not go back empty-handed or their commander would be furious. Then, amid the clamour, one of them with a grin said, ‘Girls will do,’ and so we heard an order for more trucks to be despatched. One girl took out her cell phone to call her mother, but it was instantly snapped from her. She began to cry, others began to cry, pleading to be let home. One went on her knees saying ‘Mister, Mister,’ which enraged him, so that he began cursing and taunting us, calling us names, saying we were sluts, prostitutes, that we should be married and soon we would.

We were separated into batches of twenty and had to wait, jabbering and cleaving to one another until the order was given to vacate the dormitory at once and leave everything behind.

The driver of the first truck outside the school gates had a gun to his head, so that he drove zanily through the little town. There was no one about who might report on a truck passing through, at such an ungodly hour, with girls crammed into it.

Soon we were at a border village that opened into a landscape of thick jungle. The driver was told to stop and minutes after he was brought out, we heard a barrage of gunfire.

Other drivers have arrived and there is wild talk and conferring as to which girls to put in the different trucks. Terror had paralysed us. The moon that we lost for a time reappeared high up in the sky, its cold rays shining on dark trees that stretched on and on, bearing us to the pith of our destination. It is not like the moon that shone on the dormitory floor, picking up our clothes, but leaving our copybooks, our satchels and our belongings, as we were told. I hid my diary, as it was my last link with my life.

But we had not lost hope. We knew that by then the search parties would have begun, our parents, our elders, our teachers all in pursuit. Through the open sides of the truck we throw things out, in order for them to trace us—a comb, a belt, a hanky, scraps of paper with names scrawled on them—Find us, find us. We talk in whispers, and try to give each other courage.

We enter dense jungle, trees of all kinds, meshed together, taking us into their vile embrace.

We enter dense jungle, trees of all kinds, meshed together, taking us into their vile embrace. Nature had gone amok here. The terrain underneath is so rugged that even the motorcyclists, who have been riding along to stop us from escaping, keep losing their grip and are thrown onto high embankments. Rebeka says to me, ‘Let’s jump for it,’ but I hesitate. She says, ‘Better die than be in their hands.’ She has been praying to God ever since we left that school and God has told her that these are bad men and that we must flee. Seconds passed and I still see it as in a mirage, that gap between two trucks, Rebeka grasping an overhanging branch, swinging from it, and then jumping. I thought, she is somewhere on that ground, dead, or maybe not dead. My nerves failed me and moreover, one of the leaders bellows, ‘If any one of you jumps, you will be shot.’ They must have assumed that she was dead.

The trucks lurch on and we are jolted hither and thither. Aisha, who had dozed for a moment, comes awake, shouting her mother’s name. Wrenched from a dream, she starts to cry. Someone puts a hand over her mouth, otherwise we will all be beaten. We are terrified. We have nothing more to throw out. We had gone too far to be traced.

• • •

There is only Babby and me now. She cries from the pit of her empty belly, hoarse savage cries and I say to her, ‘You have no name and no father.’ I bark at her. Sometimes I want to kill her. My breasts are the size of egg cups and she is tugging at the nipples, as if she too wants to kill me. We search for a well, because the water in the ditches is brown and muddy. It tastes foul. We drink the clear water in the cavity of the big rocks. I cup my hands in it and she laps it up eagerly, swallows it, as if she might choke. Those are our moments of grace, fresh water, a little reprieve from thirst and hopelessness. I have no notion of what day it is, or what month, or what year. All I know is that the air is scudded with sand, sand blowing in from the Sahel, that scrapes our eyes and half blinds us.

Where there are no trees, the earth is an ochre yellow, scored with deep zigzag lines, quite a picture, and the young curled leaves are starting to sprout on the tips of the branches. In the night, when I lie awake, I see sky. A vast violet expanse of sky, a land of beauty that has become a place of woe. So many dead girls. The sad soughing of the trees.

Sometimes I wake in a dream with wet eyelids, a dream of a person I must have known or even loved.

I lay her down, with her head pillowed on a bit of raised turf. It is the only time she sleeps. I sleep in snatches, for fear of what might befall us. Sometimes I wake in a dream with wet eyelids, a dream of a person I must have known or even loved. But this is not the time for either memory or pathos. Occasionally I hear the barking of dogs in the distance. I have not sighted a single human being in days, and I fear that when I do, we will be dragged back for the bloodiest end.

I am unable to pray in my old tongue, as they bombarded us with their prayers, their edicts, their ideology, their hatred, their Godliness.

Edna O’Brien has written more than twenty works of fiction, most recently The Little Red Chairs. She is the recipient of numerous awards, including the PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature, the Irish PEN Lifetime Achievement Award, the National Arts Club Medal of Honor, and the Ulysses Medal. Born and raised in the west of Ireland, she has lived in London for many years.