They gave me a little plastic and cardboard camera. They said go home. Report back. It was Easter weekend in Southern New Mexico. I took the thing around and wound it up and pointed it at different potential epiphanies. But the little plastic box was too small to stuff in all the magic. Same with the book I wrote about home which, I fear, I filled up with too much darkness. The great thing about writing a depressing book: you feel you’ve got to make up for it. You get quicker to seek love, to pass it on. These photos are mostly all at dawn or dusk. I was looking to learn the light.

RESURRECTION

Signage-as-prayer. Just a few hundred yards south of the New Mexico Museum of Space History in Alamogordo. They display many retired rockets there. The rockets are also faded, also prayers. We will win. Or get away. But if we don’t, remember: every day is a second chance. I always marvel when I come home and this sign is still standing, still preaching.

INSIDE/OUT

Backyard from the window of my childhood bedroom. Look close at your screen to see the screen of the window, made almost invisible by my attempt to document it. Look closer, beneath the Kokopelli momma hung out on the wall: a hole in the screen, for a straw, for surreptitiously exhaling weed. Cut a hole in your screen. Breathe through it. See the invisible. Momma has a sign on the wall that says WHOOP.

PIPE TO PLAYGROUND

Every day, a balancing act across the arroyo to get to the elementary school. Sometimes I would run because I could not wait. See the playground on the other side? I wanted to play. I don’t remember ever falling. When you fall you say Whoops. When you play you say Whoop. Despite the forlorn look of the place, we have always been whoopers.

CAFETERIA

Lazy stained-glass mosaic as we ate our government cheese. They tried all kinds of window tints to keep out the heat. Still, the light found a way.

EVERYTHING OUT WEST IS CLOSED

This was a thrift store. Now it is a metaphor. The frontier always meant something else. But: come again.

TRANSFORMED

At the turn of the 20th century, Alamogordo was a lumber town. The trees from our mountains were made into railroad ties. California filled up with people chasing their dreams, chugging over our trees. In the movie Transformers (2007), this is where Shia LeBeouf first sees a transformer transformed. Optimus Prime stands by our sawmill and calls all the Autobots to gather, to protect the world from Decepticons. His signal is shot into the clouds above town, a giant beam of light. Eventually, the world is saved.

SPACE

Because we have so much space, the light seems to travel farther.

CENTURY PLANT

It is not a cactus. It is agave. They call it the Century Plant because supposedly it only blooms every 100 years. But that is wrong. Or, as I say in the book, time here is folded over on itself. The agave only blooms once, straight from the heart, and then dies. Cut the heart out before it blooms. Roast the heart. Crush the heart. Ferment the crushed heart in hot water. Distill the mash of the heart. Finally: mezcal. Drink. This is a good way to get lit up.

PRICKLEY PEAR

Poor prickley pear. You are the saddest of the cacti. You are full of rats and your fruit is called tuna. You are not as pretty in silhouette as saguaro. They do not put you on the covers of books.

SLEEPING LADY

From Grandmommy’s old house, at dawn she is the only bright spot on the horizon.

THE ONE TRUE LIGHT AND THE WAY

On Good Friday I hiked up a mountain at Three Rivers, chased by the sunrise, with some of the folks from the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium. You can read about their struggle with the legacy of atomic testing in the book. Here they are meditating at one of the Stations of the Cross that are installed all the way up the mountain. This is the exact corridor in which their parents and grandparents were exposed to fallout after the world’s first atomic bomb test. The government still does not officially acknowledge that anyone was harmed by the test at Trinity.

SUN

Discussion of the Bomb always includes discussion of our sun. I guess the sun is a kind of nuclear explosion that just keeps on exploding, for now. They call July 16, 1945—when the first atom bomb was exploded at Trinity—the day the sun rose twice. They say the blast was brighter than a dozen suns. They say it was 10,000 times hotter than the sun. A homonym: after observing the blast, the director of the Trinity project said, Now we are all sons of bitches.

ZIA

New Mexico has the best flag. It is nothing but a sun, surrounded by light.

The American flag is so cluttered with stars, so many nuclear explosions that just keep on exploding.

CHURCH

On Easter they fellowship outside. Look at the fresco on the ceiling of that chapel.

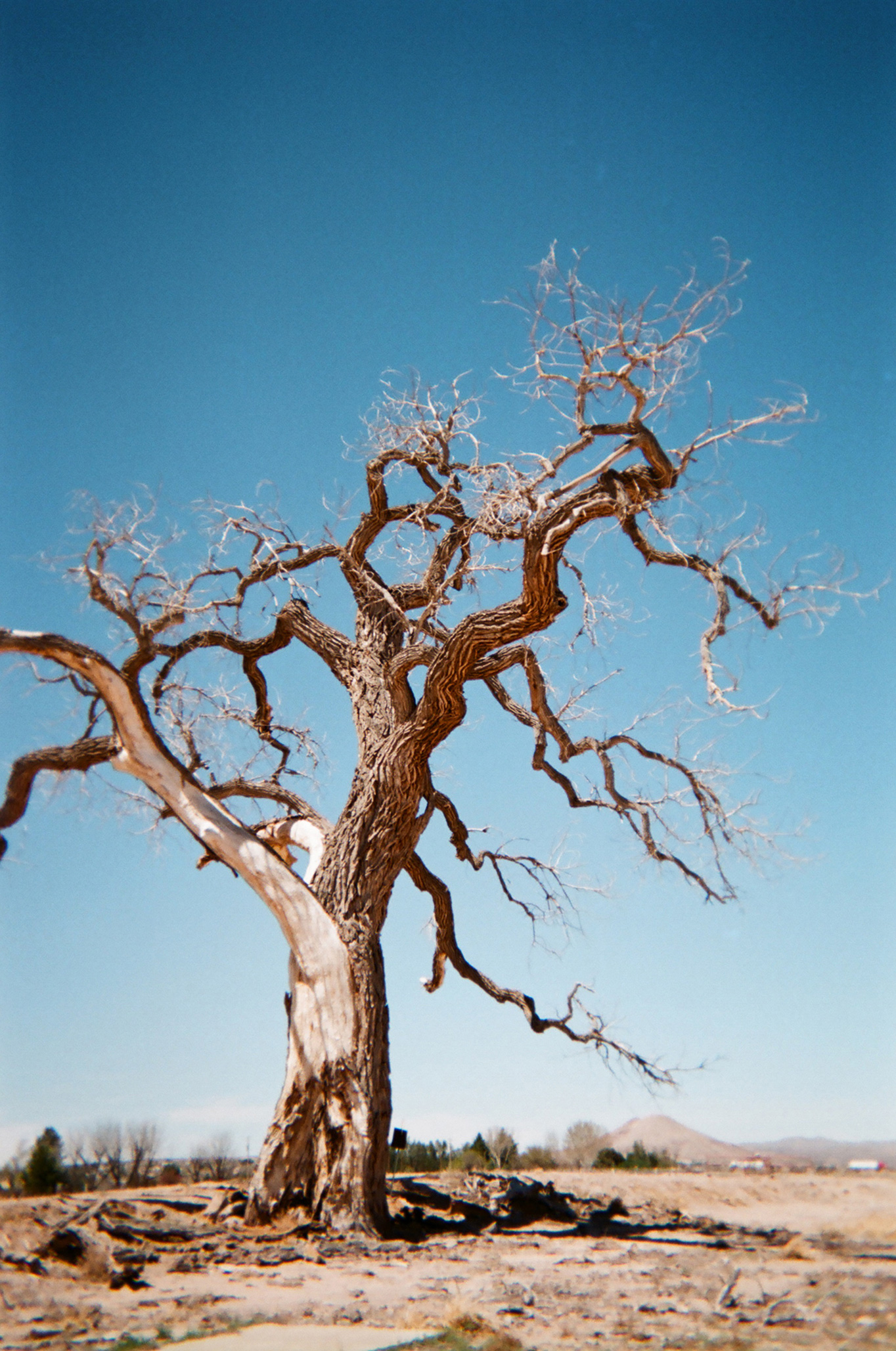

TREE

It is dead. It has not, for many years now, used light energy to convert carbon dioxide and water into sugars. On the inside, it has no use for light. Still, it basks. Goddamn, it basks.

MAGIC MOMMA and POPS

Up at Aunt Yvonne’s, just before an Easter dinner of enchiladas, I made my parents walk out into the sunset and pose. I told them I thought the light was just right. They did not complain too much. Pops discovered the engine block of that Volkswagon was full of squirrels. We had a good laugh and then I told them to stop smiling and act cool.

MATRIARCHS

Aunt Yvonne and Grandmommy. You should have seen them on horses back in the day. Even now the desert parts and bows down as they walk through it.

JOHNNY’S CHILE FREEZER

We freeze the chile sauce so we can feel the heat year round. Just after harvest, the bags bulging with red sauce fill the whole freezer. You open it and see what looks like a professional collection of blood. But we are not vampires. Chile is a form of light. Aunt Yvonne has long been the best at burning our mouths and draining our heads, but these days her son Johnny has gotten into the game. He has his own freezer, with his own blend. He keeps his ground chile paste in mason jars labeled XXX. He can turn the fire up until your eyes ignite. Everybody keeps bugging him for more. Now his freezer is almost empty. So he’s gonna start a business. He is on the hunt for investors. It is not often you have the opportunity to get in on the ground floor of a miracle.

If ever there is any chile we cannot eat, we use it as décor.

THE VIEW FROM MY BUDDY NEAL’S BACKYARD

They call those the Organ Mountains. Listen to them bellow in harmony with the sun.

CROSSROADS

Ryan Bemis at his acupuncture clinic, standing in front of a painting of the Organ Mountains (by Meg Freyermuth). Acid West includes the story of Ryan’s work training nuns in Juarez to use needling, in the wake of cartel warfare, as a low-cost form of healthcare for their communities.

SHROUD OF TURIN

If you want to know why the Shroud of Turin museum is in Alamogordo, and what that has to do with Atari videogames, then buy (and read) Acid West. One theory for how the shroud was imprinted with the image of Jesus: he emitted divine light as he resurrected.

WHITE SANDS MOTEL

Many people come out of this motel looking resurrected. But I have not heard any stories about divine imprints on the sheets.

MATRIARCHS 2

Somehow I accidently wound the camera and took an extra shot of Aunt Yvonne and Grandmommy. I’m glad I did. They seem to be ascending.

Joshua Wheeler is from Alamogordo, New Mexico. His essays have appeared in many literary journals, including The Iowa Review, Sonora Review, PANK, and The Missouri Review. He’s written feature stories for BuzzFeed and Harper’s Magazine online and is a coeditor of the anthology We Might as Well Call It the Lyric Essay. He is a graduate of the University of Southern California, New Mexico State University, and has an MFA in nonfiction writing from the University of Iowa. He teaches creative writing at Louisiana State University.