I am thirteen. My mom and I are walking down a hallway in the wing of a San Francisco art museum and pass an auditorium. I can hear a voice on the other side of the door, loud, accented, lilting and rolling and sure of itself. Books are stacked high on a table outside the door. I’ve never been to a reading, don’t know that’s what this is, don’t know whether we’re allowed inside but before I can fret about it, my mom smiles at me conspiratorially and walks inside. I follow.

The auditorium is chilly and full. The people are quiet, staring at the woman. There is a feeling of seriousness in here that I immediately love, a sensation I am constantly rooting around for as a young person. I don’t much care for humor, or lightness. I want to know the truth about things, the real answers. I want to be taken seriously. Nobody takes a child seriously.

On stage is Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, I learn. She is reading out loud from a book of her poems, Leaving Yuba City. The audience wants to know her story, the woman she is and was and is becoming. The sounds that come from her are clouds moving across the horizon, and thunder, and cinnamon in hot chocolate, and rusted metal, and the unfurling of a new lime-green fern. What I mean is, my stomach is flipping upside down, like some sleeping snake in my belly has finally been charmed awake. What I’m saying is, I felt suddenly alight.

My mom sees something—some alien sheen on my eyeballs, some hair standing straight up from my arms—and buys me two of Divakaruni’s books when the reading is over, a novel and collection of poetry. The novel is a hardback. It costs almost thirty bucks. Thirty dollars! For a book! And fifteen for the poetry. I mean, come on. This kind of reckless spending is unheard of. I am only allowed three school lunches a month because they’re too expensive at $2.50 per meal.

These two books become diamonds once they reach my hands, worth that much, and they are mine, they are serious, they are books of spells. Most of my childhood and adolescence I feel isolated, unwanted, but in this moment, I do not. I feel like my mom has seen the snake of me and is buying it expensive food to keep it alive.

I stroke these books, spinning them over and over in my hands. Begin reading. I read the novel. Read the poems. Again and again. I read “Cutting the Sun” and feel myself unfolding. What I love about this poem is that it makes me feel both afraid and defiant. The scale of this poem is thrilling—the sun is at once “gigantic-hot” and able to be cut open with only a pair of scissors. The poem operates with a kind of dream-logic, where the speaker suddenly has scissors in her hands (“where did [she] get them?”), the same logic that startled me awake last night, now, twenty years after I first encountered Divakaruni, shouting to my husband that birds were pecking away my hands. But in this dream-not-dream poem, the speaker takes scissors and cuts right into the sun that is trying to take her name. And what is inside the sun? Flowers, flowers, flowers. Past the fear, there is beauty—though, the speaker here is “not afraid.” It is just my fear, perhaps. She holds in her hands something powerful enough to cut through whatever arrives.

She holds in her hands something powerful enough to cut through whatever arrives.

I’ve never seen the painting to which this poem alludes, Francesco Clemente’s Indian Miniature #16, and, in truth, did not know what that meant for the first years I had the book. But I like that one piece of art helped create another, this poem, which made a new, though connected, idea in a faraway brain. And so Francesco Clemente has infected me, too, through a game of art-telephone.

“Cutting the Sun” is a nature poem—sort of. It is a poem that makes a new kind of sense to me here in South Carolina, where I’ve just moved, where so much nature feels adversarial. The natural world is beautiful in the poem, and here in South Carolina too, with rays of sun “striated, / rasp-red and muscled as the tongues / of iguanas.” But those same rays are also “trying to lick away / my name.”

My husband and I just went on a camping trip over spring break into a swampy forest on the South Carolina coast, and there, we encountered packs of wild boars, gators, snakes, swarms of mosquitoes and chiggers, biting flies, wasps, poison ivy, ticks sucking merrily in our crevices, and—though the weather was mild—in the summer, the sun and heat and humidity can kill a person. We were reminded of that often, walking on a raised path through a swamp that was dug by enslaved people who were made to work rice fields there; we were reminded of that as we swatted and doused ourselves in bug spray and hid in the car and did all kinds of things to protect our bodies, things that people who stood in the same place before us were not able to do. How easy it would be to have one’s body badly damaged here. How quickly the sun could devour you. How necessary it would be to have those big blue scissors readied to cut straight to the heart of whatever threatened until the sun’s “rays fall around [you] / curling a bit, like dried carrot peel.” The power of that—of turning the sun into nothing but dried carrot peel. The beautiful impossibility of it.

Sometimes we find the words that save us. Sometimes the words find us. I stumbled upon Divakaruni by accident, the first writer I laid eyes on, and I latched on to her words with the devotion of a first love. I still feel it. Enchantment. I celebrate her work, these beautiful and accessible poems, which still enfold within them a complication, a contradiction, a feeling bigger than the words literalize. These poems which still move me.

Sometimes we find the words that save us. Sometimes the words find us.

I celebrate this poem that burrows deeply into a thirteen-year-old, that changes over time as that girl grows, that opens the door to other poems, narrative and figurative, lineated and blocked, contemporary and old; I celebrate getting the right poem into the right hands by whatever accidental snake-storm alien eye-glow makes that happen; I celebrate the way so many years later, in a swamp across the country from where I was raised, I experience her words again in nature’s sublime danger, in the terrible history that is part of many of the physical places we visit in this country, in nature poetry that is also necessarily about its humans and must make us take responsibility for our human history, in the sun, of which I am afraid, of which I am not afraid, I celebrate poetry, here’s to poetry, and I celebrate my mom for spending finite and precious money on books, for deciding we too could belong in an author’s reading, I celebrate the poems that let us take ourselves seriously enough to then learn not to take ourselves so seriously; I celebrate the very serious girl-becoming-woman I was at thirteen who finally, finally read that she could use whatever logic she wanted to hold scissors against that which wanted to strip her of who she was becoming.

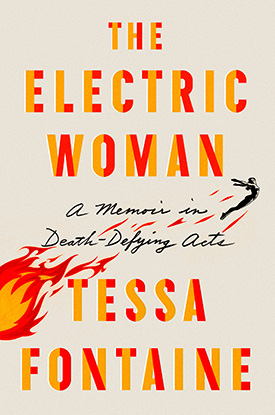

Tessa Fontaine‘s writing has appeared in PANK, Seneca Review, The Rumpus, Sideshow World, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from the University of Alabama and is working on a PhD in creative writing at the University of Utah. She also eats fire and charms snakes, among other sideshow feats. She lives in South Carolina. The Electric Woman is her first book.