We had filled our backpacks with peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. We also threw in thermoses of chocolate milk we’d mixed ourselves. We thought the milk would stay cold. At the bottom of our backpacks shook boxes of pellets for our pump-styled air rifles. They were for the rambunctious squirrels. We knew we’d eventually find them spiraling up and down the trunks of oaks. The day before, in preparation, we’d taken out our pocketknives and made cuts in the soft, flat heads of the lead pellets. The cuts were meant to create a weak point in the very middle, so that the pellet would split apart at impact. We wanted to send fragments in different directions. We weren’t thinking about what other damage that would do.

We spent the day wandering deep into the woods, beyond any remnants of a marked path. At one point, we spotted a trailer. Its roof was covered with fallen branches, and the thin metal sides held a fur of rust. The rest of the squat, rectangular structure looked pieced together with rippled patches of moss. It didn’t seem real, this trailer, let alone safe, but being children, we did what others in a long line of careless souls would’ve surely done: we went inside. I should mention here it wasn’t even on a dare. It was just an assumed activity. You see a dangerous thing as less dangerous from within.

The floorboards had mostly rotted, and there were translucent glass bottles of all sizes, some packed with dirt. The bottles lined the bowed countertop in a gradual curve. I thought I was staring at a bottom row of giant, crooked teeth. For some reason, my friend had started opening cupboards and slamming the doors like he was looking for something specific. I stepped cautiously across the floor, over to the other side of what must have once been the kitchen area. Vines, having pushed in from creases in the ceiling, had grown down and into the sink. Screens that once lined a row of windows had all but disintegrated, the metal filament infinitesimal as blown strands in a punctured web. My friend started jumping up and down like he was on a trampoline. The paneled walls shook, and the last of the floor joists threatened to finally give.

That’s when I felt the soft hive fall across my face.

My skin shivered with the collective electricity of their stunned bodies.

There were so many hornets. They were like water. My skin shivered with the collective electricity of their stunned bodies. I ran from the trailer. I pulled at the buzzing chunks, slinging them from my hands. My hair shook. My breath left me in a sudden burst and, terrified, I only drew it back in, heaving the more I ran. Then the trees finally stood still, and I fell to the ground and ran my fingers all over. I was frantic and searching for some clue that was hidden in my skin, though I couldn’t find it. After I calmed down, I stood up. I stared back at my friend. He was holding up our backpacks. I didn’t know where our pellet guns were, and I didn’t care. I was laughing now. I hadn’t been stung, and neither had my friend.

In another ten years, I had all but forgotten the trailer and the enormous hive that had fallen on my head. At the university where I was enrolled as an undergraduate, I signed up for a Survey of Poetry course, and one of my first assignments was to write a paper on Marianne Moore’s famous poem “Poetry.” I remember smirking at what I thought was the speaker’s ingratiating dismissal in that opening line, “I, too, dislike it.” I’m a little ashamed to admit I wasn’t initially captivated by Moore’s work, but I remember returning to the phrase “imaginary gardens with real toads in them,” and the more I did so, the more the line took on meaning for me (even though I’d go on to receive a mediocre grade on my paper). After the course was over, I went in search of more of Marianne Moore’s work. I’m sure I resisted the precision of her poems, but it was exactly this shaping of imagination that encouraged me beyond my confusion, that let me enter into poems with little, if any, caution.

Later, in an upper-level poetry workshop, my professor would introduce me to Elizabeth Bishop’s work, another poet who utilized clarity and compression, and I would sometimes go on to lose whole evenings in the stacks of our university library, reading Bishop and sometimes returning to Moore, though not at all realizing these two poets had, in fact, been close friends. It wouldn’t be until I opened the book One Art: Letters of Elizabeth Bishop that I would see the evidence of the two poets’ correspondence. In one letter, I remember there was reference to Elizabeth Bishop having sent Marianne Moore a scale from a parrotfish Bishop had caught. That one image struck me, and it was this smallest of fragments that sent me back.

That one image struck me, and it was this smallest of fragments that sent me back.

I thought about the pocketknife I had used to slice an X onto the flat heads of the lead pellets, how we didn’t find squirrels that day, and how plenty of those pellets would go on to never be used at all. I can’t say where we stopped to eat our sandwiches, only that we did, and that it was quite a distance away from the trailer. My thermos had suddenly seemed so large. I had to hold onto its sides with my hands flattened, the webbing of my fingers outstretched. The milk had warmed, but I still drank it. I don’t remember ever leaving those woods.

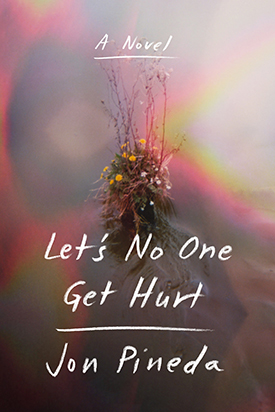

Jon Pineda is a poet, memoirist, and novelist living in Virginia. His work has appeared in Poetry Northwest, Literary Review, Asian Pacific American Journal, and elsewhere. His memoir, Sleep in Me, was a 2010 Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers selection, and his novel Apology was the winner of the 2013 Milkweed National Fiction Prize. The author of three poetry collections, he teaches in the MFA program at Queens University of Charlotte and is a member of the creative writing faculty of University of Mary Washington.