The questions of where a story should go can be paralyzing, especially in the beginning, when anything is possible, and especially if you’re not the type of writer to make a plan, which I’m not. To get through this hairy time, I’m likely to pass off the responsibility of the first draft to what amounts to a roll of the dice. I’m mouthy about not believing in writer’s block. Why stall before beginning, or even pause while writing, when you can take a chance and see what happens? Why worry over what to do next when you can wager on a single possibility? The first draft of The Grip of It was built on such accidents.

The forward momentum of the story is dependent on what is seen and heard and the way those things affect how James and Julie (the protagonists) feel. This narrative thrust relies equally on how their feelings (about themselves, toward each other) can affect the things they see and hear. James and Julie construct stories based on what they believe to be happening around them, and it’s possible that they misinterpret some of those clues, that the two of them read the clues in different ways, that the clues contradict each other, making a mess of the story that will let James and Julie finally relax and enjoy their new home.

In the book, James and Julie are living in a city when James develops a gambling problem. Julie convinces James they might be happier with a simpler life in the country, so they find a good deal on an old house and start fresh. The couple is already cognizant of the distance between them, and hope the move might close the gap. At first, they write off concerns—an electrical hum, a nosy neighbor, the teeming rhythms of nature in the woods behind the house—convincing themselves they need only to become adjusted to their surroundings. They keep secrets from one another in an attempt to maintain what little composure they’ve reestablished.

I started the book knowing I wanted to write about a haunted house, but not much more. I had recently become obsessed with the work of a South African photographer named Roger Ballen. Known for blurring the boundaries between documentary, painting, theatre and sculpture, he tests what the viewer believes to be “reality” in his photography.

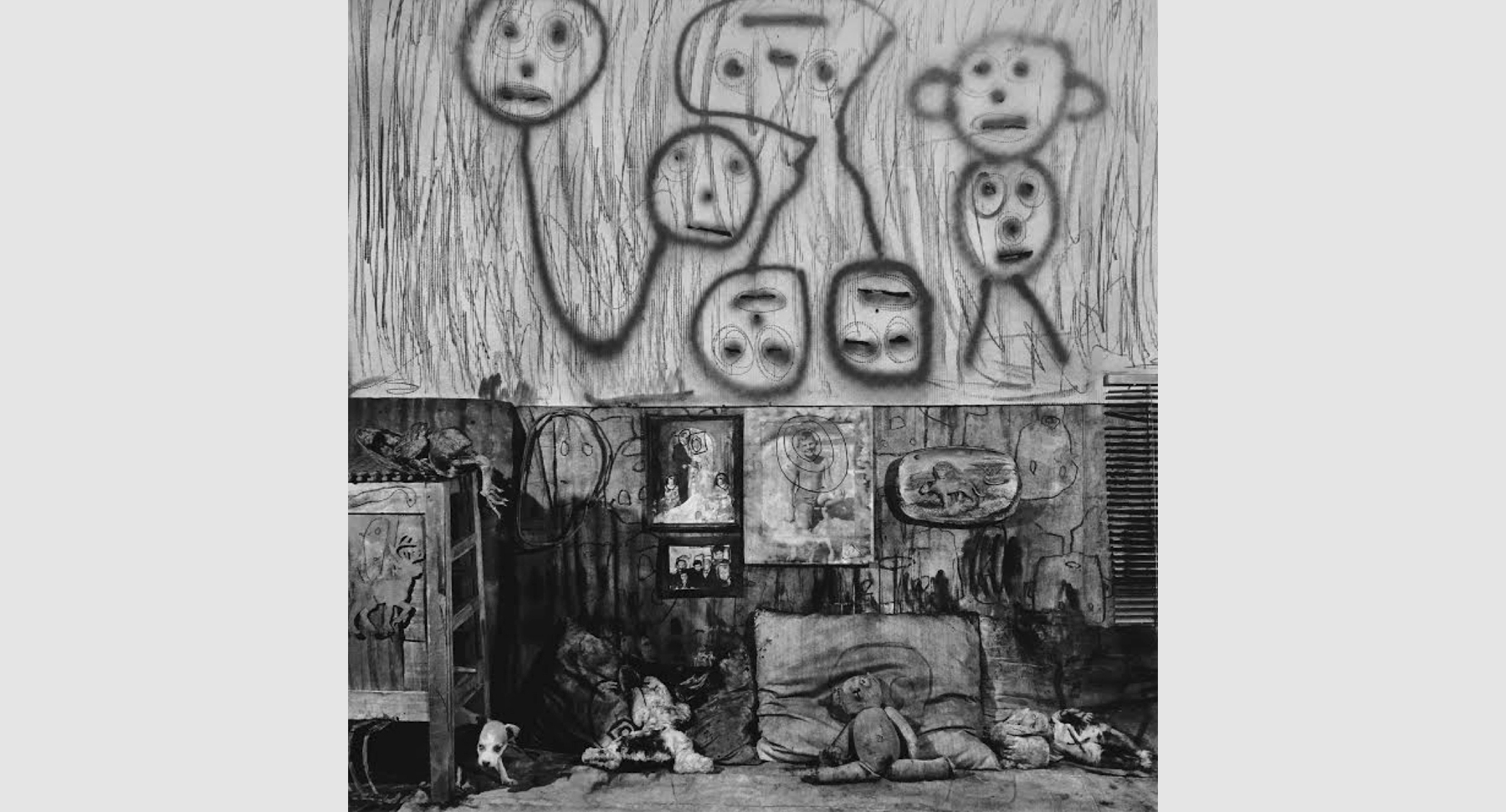

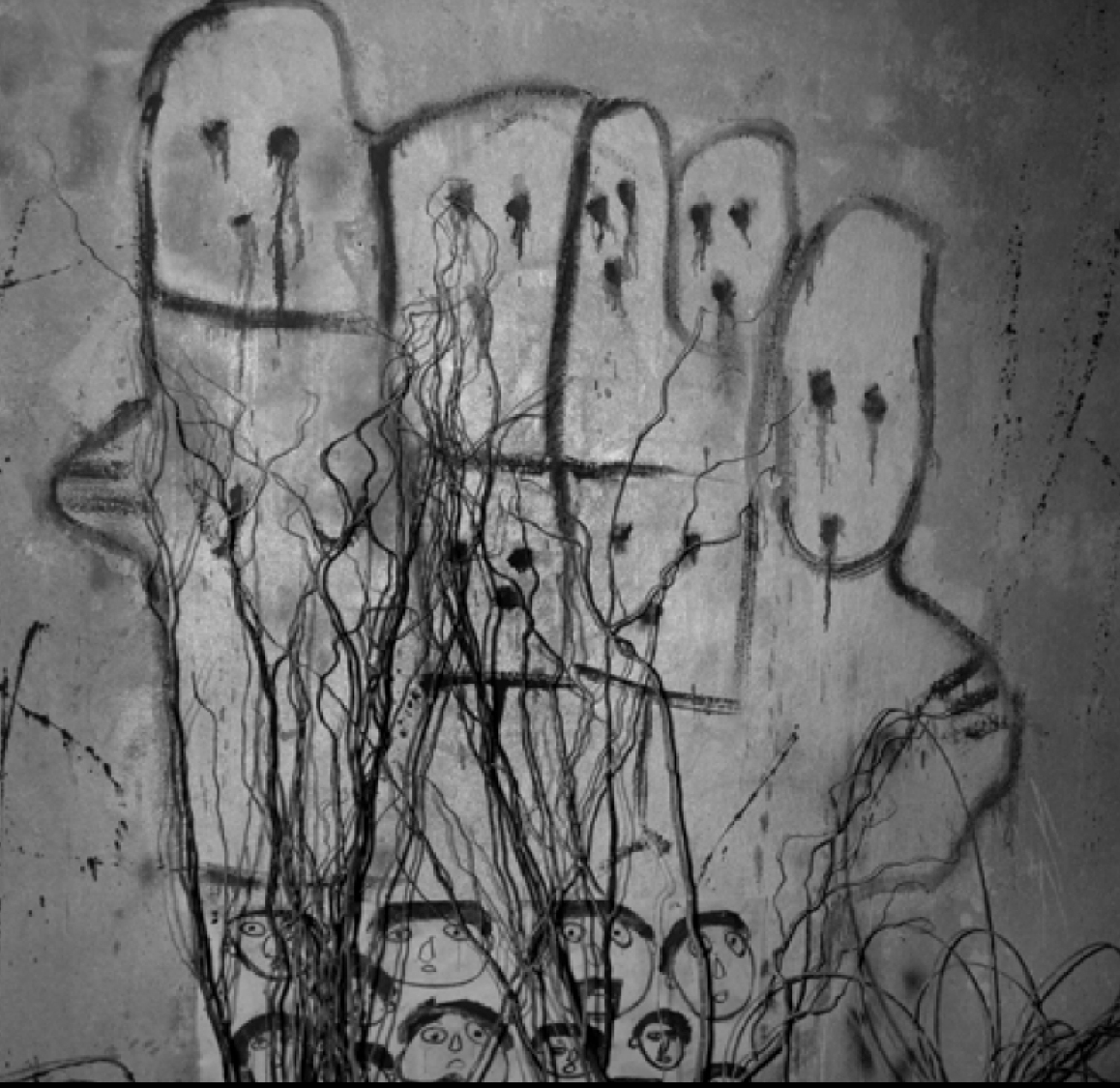

Asylum by Roger Ballen

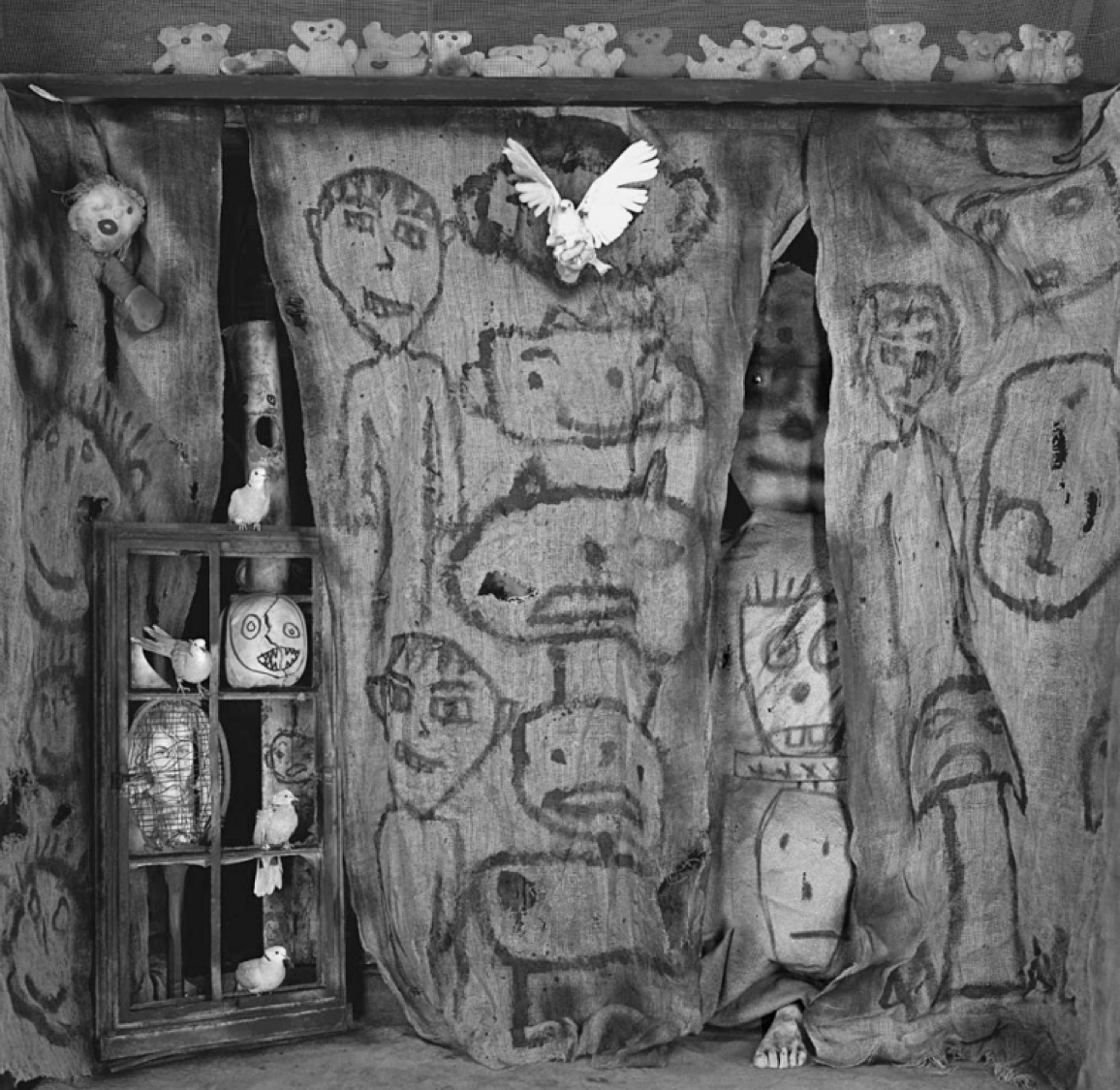

A fabricated creepiness distracts from the even more disconcerting natural elements. Ballen’s crude scribbles pull your attention, but then patience with the image is rewarded with a deeper uneasiness. A splayed hand emerges from a torn sheet holding a struggling dove. A fold in the curtain betrays a single foot.

Muybridge’s Horse by Roger Ballen

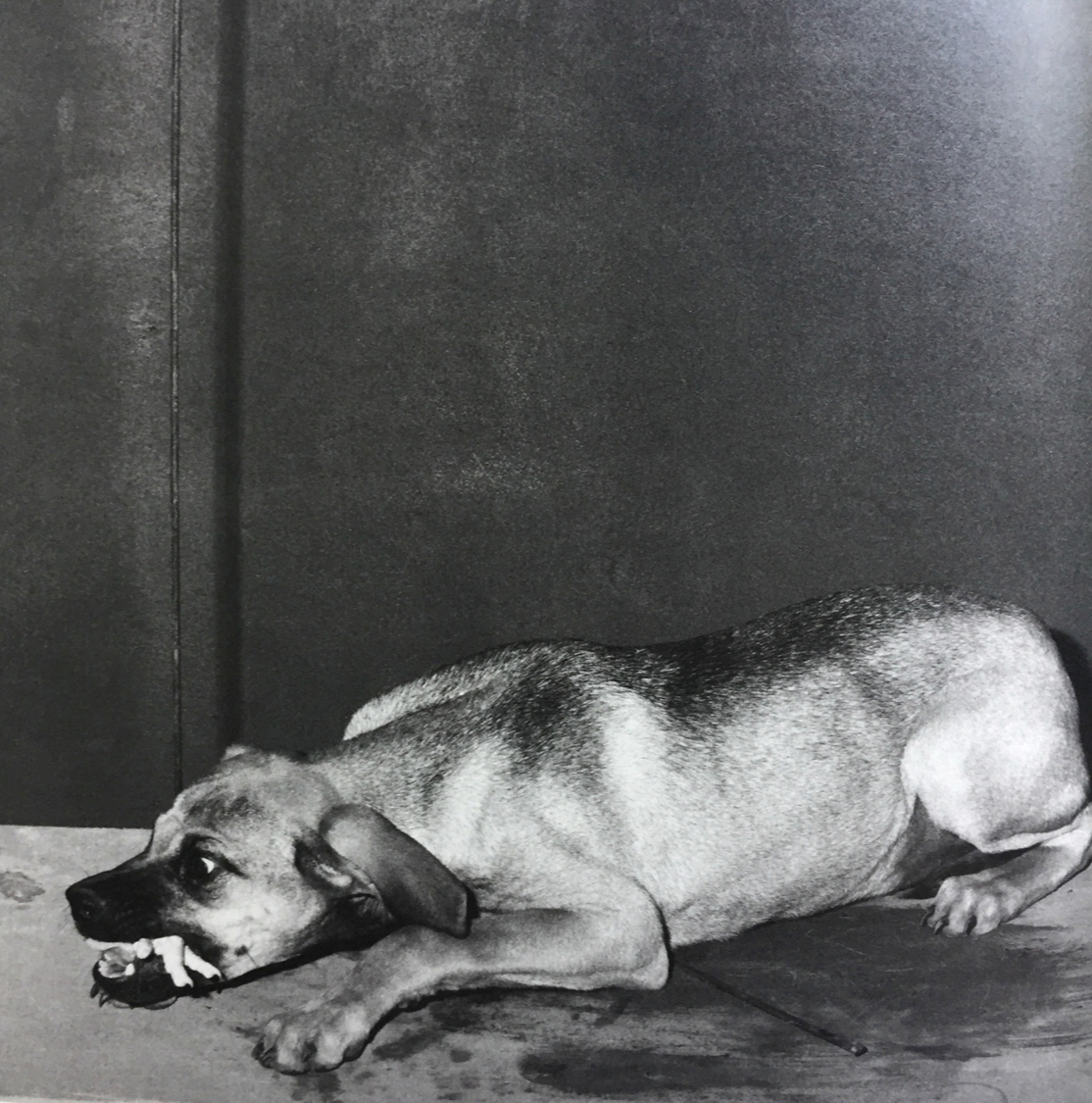

Dirt and drool smudge the people depicted. They fumble with props—broken objects and restrained animals. The reality of the filth feels honest and upsetting.

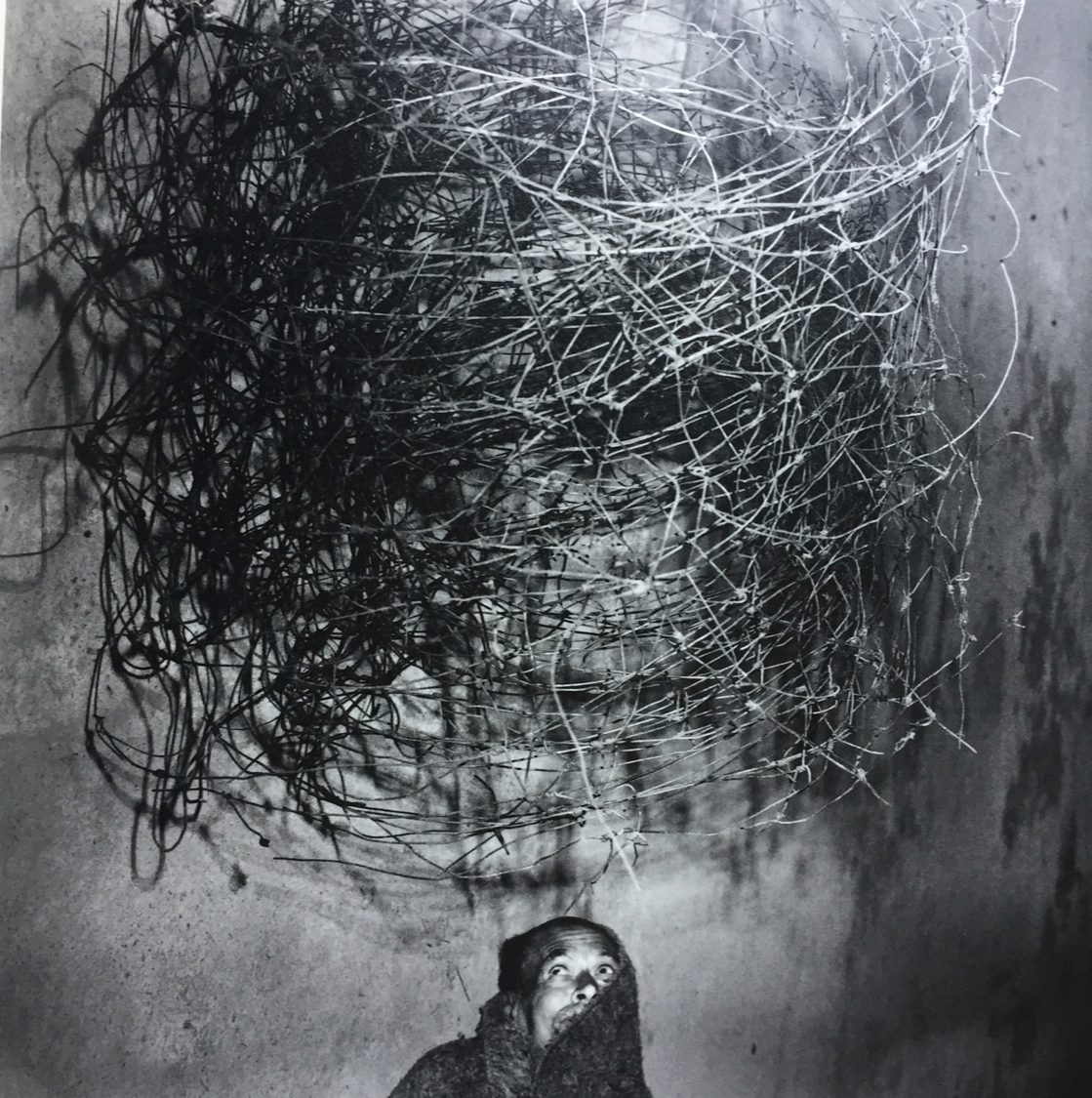

Twirling Wires by Roger Ballen

Something is always just out of sight. Something hovers overhead and shifts away too soon.

Funeral Rites by Roger Ballen

Even the stationary expands and changes. Even the inanimate buzzes with a cunning life.

There is nothing technically impossible about the images Ballen creates. One can imagine a reason for any single one of his images existing naturally, but when seen in succession, they compound and confuse. Who are these people? Where are they? What is happening and why? They are both far enough away from everyday experience that the viewer is also willing to make excuses for why they could be real, but extraordinary enough that they seem false, too something to be true.

I used Ballen’s images as a guide in this way, trying to match the way uneasiness grows the more one experiences or sees of the unreliable world created. Any small anomalous event can be brushed away, explained, but when enough of them add up, the fear becomes unavoidable.

The house that James and Julie live in isn’t as squalid as the interiors of Ballen’s images. Their house is clean, well lit. It’s the dynamic that develops between James and Julie that becomes fallible and untrustworthy.

I kept two books of Ballen’s photography open next to me while I was drafting: Boarding House and Shadow Chamber. When I didn’t know where the story should go next, I rolled the dice. I turned to a new image of one of these books to decide what would happen on my next page of writing. Sometimes the translation of image to the page was very literal and sometimes an interpretation.

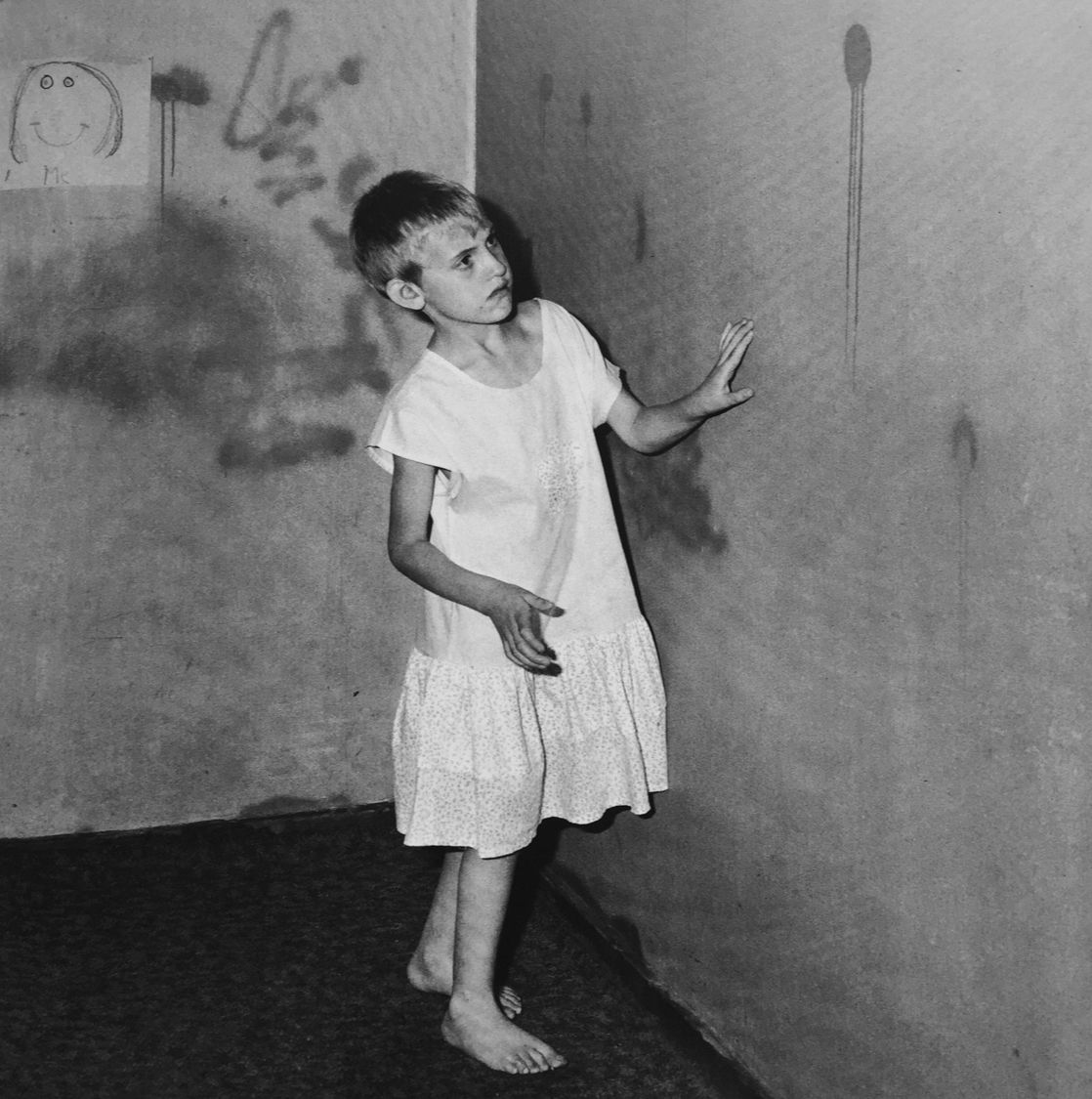

Girl in a White Dress by Roger Ballen

When they find the stain on the wall and wonder if it’s growing.

Engulfed by Roger Ballen

When James suffers Stendhal syndrome looking at a photograph.

Cloaked Figure by Roger Ballen

When drawings appear on the wall and both James and Julie assume it was the other one who made them.

Hanging Pig by Roger Ballen

When James tells Julie the story of a person being trapped with his pet dog.

Hungry Dog by Roger Ballen

When the neighbor goes missing and a dog shows up with fingers in his mouth.

In drafting I strung together a narrative from these clues. I passed the clues on to James and Julie to examine themselves. In revision, I eliminated many of the clues that didn’t end up accruing, agreeing or contradicting in ways that seemed rewarding. I added different iterations and echoes of the clues the images had initially provided, trying to point Julie and James to answers that might satisfy them. In the end, each character comes up with a balance of solutions individual to them, as I assume each reader will, as well. There are a lot of answers in The Grip of It contingent on who the reader decides to trust and when, and, in this way, the questions, as absolute, remain more dependable than the answers.

Jac Jemc is the author of My Only Wife, a finalist for the 2013 PEN / Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction and winner of the Paula Anderson Book Award, and the short story collection A Different Bed Every Time. She has been the recipient of two Illinois Arts Council Professional Development Grants, and in 2014 was named one of 25 Writers to Watch by the Guild Literary Complex and one of Newcity’s Lit 50 in Chicago. She recently completed a stint as the writer in residence at the University of Notre Dame and currently teaches at Northeastern Illinois University and StoryStudio Chicago, as well as online at Writers & Books and the Loft Literary Center, and she is the web nonfiction editor for Hobart.