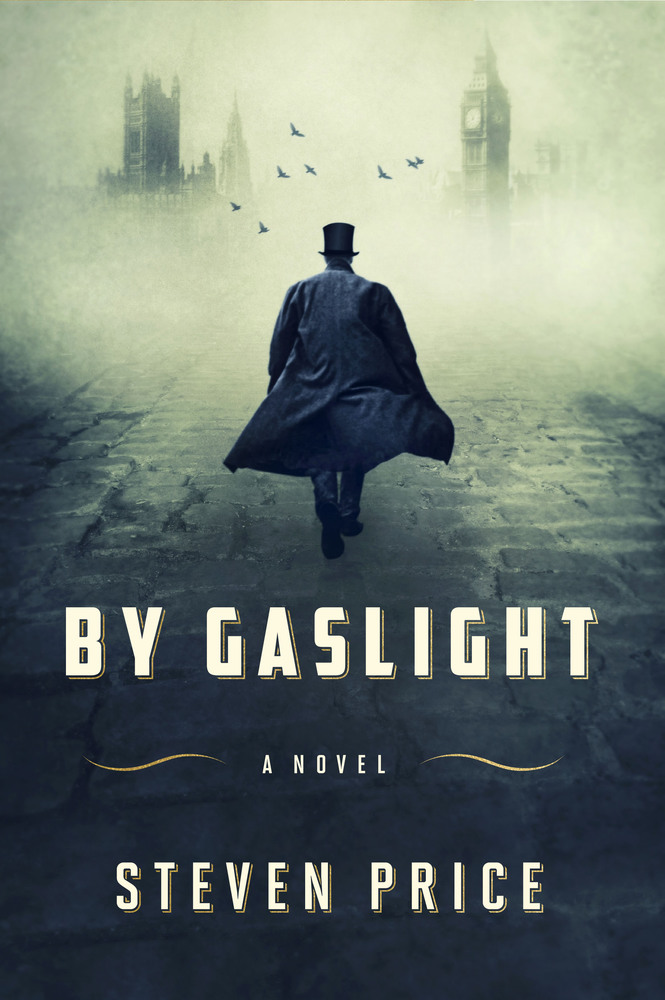

Steven Price

In 2001 I was living in Charlottesville, reading poetry at the University of Virginia, a young Canadian who had never been in the southern states before. In my second week I bought a beautiful used set of Shelby Foote’s Civil War volumes. Six weeks later, I turned back to the first volume and began reading the books for the second time.

opens in a new window |

What was astonishing to me was the feeling of lived history in the landscape surrounding. I was born on the west coast of Canada, where so much of the land stands emptied, its historical memory lost with the annihilation of vast swathes of its First Nations peoples. But I remember with great sharpness the feeling of walking Virginia’s back roads—the sun-dappled trees, the stillness and soft green light—startled by the knowledge that the very landscape itself had been altered by war, and that the earth was still filled with evidence of its suffering.

• • •

At the heart of By Gaslight is an encounter and a betrayal in Virginia in 1862, in the midst of the Civil War.

I did not come to the novel with the Civil War in mind. I started instead with the character of William Pinkerton, the real-life son of Allan Pinkerton, founder of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. But William had served in the Civil War, and the deeper I read, the more I came to see how completely William’s generation must have been shaped by the fierce horror of that conflict. William was sixteen in 1862, when he went south with his father’s spies on the ill-fated Peninsular Campaign.

It was difficult for me not to see, in William’s subsequent life, a life of violence and hardship and great physical courage, the aftereffects of that war. In the late 1860s and early 1870s William became one of the most-feared hunters of the western outlaws—men themselves who had been forged in the atrocities of the Civil War. The Wild West, then, was marked by veterans of that conflict, young men who had witnessed great violence and for whom a world that denied such violence must have made little sense.

Gradually, By Gaslight fumbled its way toward these stories. Historical fiction exists in the absences, in the gaps in the historical record. It needs to be plausible but also unverifiable. In the course of my reading, I came across two books that helped me find those gaps in the Pinkertons’ war. Jay Bonansinga’s Pinkerton’s War was an invaluable source for tracing the details and events of those days. And Stephen Poleskie’s excellent biography of Thaddeus Lowe, The Balloonist, charted the use of Lowe’s aerostats in the Union war effort.

• • •

A cryptic reference in one history of the Pinkerton Agency to a sixteen-year-old William, ascending over the battlefield of Malvern Hill in the world’s first combat reconnaissance balloon, intrigued me. I started digging.

What I found surprised me. In a war that saw the first armored steamships, the first use of barbed wire, the first large-scale use of industrial warfare, and the first Navy submarine, it seems that war balloons—or aerostats, as they were known—were among the most advanced secret military technology of the 1860s. They remained rare and expensive and required the expertise of balloonists, who were a motley group—egotists and daredevils mostly. The Union forces had three aerostats; the Confederates desperately wanted one, and attempted to build one out of silk dresses donated by the women in Richmond. They were never entirely successful. But the Confederates came to view the enormous alien moons of the Union aerostats as terrible things, and sent snipers and raiding parties across the lines in desperate attempts to sabotage them. The advantages of aerial reconnaissance seem obvious to us now in a world of spy satellites and advanced intelligence. But in 1862 the newness and unlikeliness of the aerostat seemed to the conservative generals of the Union forces a kind of vanity, a foolishness hardly worth pursuing. The project was eventually abandoned.

The balloonist and showman Thaddeus Lowe had offered his own aerostat to the Union forces at the outbreak of the war, in exchange for command of the nascent U.S. Air Force. A complicated man, Lowe wanted desperately to be of service to the Union. But he wanted, too, official rank in the Union Army and wanted to use that rank after the war as a credential to advertise his private aerostat exploits. The Union Army never did entirely trust him. His powerful personality helped to push through the use of balloons in the war effort, but also eventually contributed to their disuse and decline.

In the novel, Lowe falls sick during the Peninsular Campaign—as so many of the Union soldiers did—and never manages to stumble out into the pages of the book.

• • •

Stories grow in the telling. So much of the act of writing is also the act of listening, of paying close attention to a book, and noticing the connections and leaps that are being made secretly in the writing itself.

It is strange to me how a novel can find its own way, can become something other than what the author imagines it to be. But gradually I have come to see that By Gaslight is, at its heart, a war novel, a novel about the wreckage of war, about war’s long shadow. I did not set out to write it this way. But I think now it could not have been otherwise. Its two protagonists, Adam Foole and William Pinkerton, are from an unlucky generation, a generation marked by storm and violence, haunted by a war not of their choosing. Somehow By Gaslight became, in the end, a story of witness, of what comes next, asking what it means to survive in a catastrophic age, when a country is divided, and willing to tear itself apart.

Steven Price‘s first collection of poems, Anatomy of Keys (2006), won Canada’s 2007 Gerald Lampert Award for Best First Collection, was short-listed for the BC Poetry Prize, and was named a Globe and Mail Book of the Year. His first novel, Into That Darkness (2011), was short-listed for the 2012 BC Fiction Prize. His second collection of poems, Omens in the Year of the Ox (2012), won the 2013 ReLit Award. He lives in Victoria, British Columbia, with his family.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE:

Jamie James on The Many Faces of Isabelle Eberhardt

The Mystery Behind the Woman who was Given Van Gogh’s Ear

Unforbidden Pleasures: Adam Phillips & Ilene Smith Discuss Agency and Desire

C.E. Morgan & Lisa Lucas Discuss the Politics of Storytelling