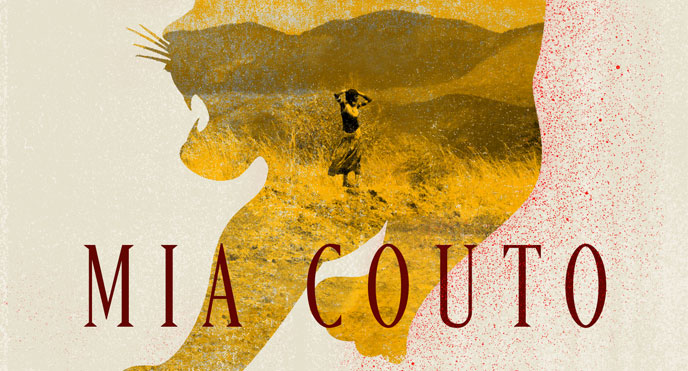

Mia Couto is one of the most prominent writers in Portuguese-speaking Africa, and his latest novel, Confessions of the Lioness, made the Man Booker shortlist. Couto combines reality, superstition, and magic realism to spin a dark, poetic mystery about the tribal women of Kulumani and the lionesses that hunt them.

There’s only one way to escape from a place: It’s by abandoning ourselves. There’s only one way to abandon ourselves: It’s by loving someone.

—excerpt pilfered from the writer’s notebooks

opens in a new window |

It’s two in the morning and I can’t sleep. A few hours from now, they’ll announce the result of the contest. That’s when I’ll know whether I’ve been selected to go and hunt the lions in Kulumani. I never thought I’d rejoice so much at being chosen. I’m in dire need of sleep. That’s because I want to get away from myself. I want to sleep so as not to exist.

*

The sun’s nearly up and I’m still wrestling with the sheets. My only ailment is this: insomnia broken by brief snatches of sleep from which I wake with a start. When it comes down to it, I sleep like the animals I hunt for a living: the jumpy wakefulness of one who knows that too much inattention can be fatal.

To summon sleep, I resort to the ploy my mother used when it was our bedtime. I remember her favorite story, a legend from her native region. This is how she would tell it:

In the old days, there was nothing but night. And God shepherded the stars in the sky. When he gave them more food, they would grow fat and their bellies would burst with light. At that time, all the stars ate, and all glowed with the same joy. The days were not yet born, and that was why Time advanced on only one leg. And everything was so slow up there in the endless firmament! Until, among the shepherd’s flock, a star was born that aspired to be bigger than all the others. This star was called Sun, and it soon took over the celestial pastures, banishing the other stars afar, so that they began to fade. For the first time, there were stars that suffered and became so pale that they were swallowed up by the darkness. The Sun flaunted its grandeur more and more, lordly over its domains and proud of its name, so redolent of masculinity. And so he gave himself the title of lord of all the stars and planets, assuming all the arrogance of the center of the Universe. It wasn’t long before he declared that it was he who had created God. But in fact what had happened was that with the Sun now so vast and sovereign, Day had been born. Night only dared to approach when the Sun, tired at last, decided to go to bed. With the advent of Day, men forgot the endless time when all stars shone with the same degree of happiness. And they forgot the lesson of the Night, who had always been a queen without ever having to rule.

This was the story. Forty years on and this maternal comfort has no effect. It won’t be long before I know whether I’m going back to the bush, where men have forgotten all the lessons learned. It’ll be my last hunting expedition. And once again, the first voice I ever heard echoes in my mind: And everything was so slow up there in the endless firmament.

*

First thing in the morning, having scarcely slept, I get ready to go to the offices of the newspaper, two blocks down from where I live. But before I leave, I take my old rifle out of the cupboard. I lay it across my legs and caress it with the loving care of a violinist. My name is engraved in the breech: Archangel Bullseye—hunter. My old father must be proud of the way an old family tradition has lived on through me. It was this tradition that justified our name: We Bullseyes always hit the target.

*

I’m a hunter—I know what it is to pursue prey. Yet all my life, I’ve been the one pursued. I’ve been pursued by a rifle shot ever since childhood. It was this shot that propelled me once and for all outside the realm of sleep. I was a child, and I slept with all the aptitude that children alone possess. The blast tore through the night and the world. I don’t know how, in response, I managed to run down the length of the corridor: My little feet were rooted to the floor. In the living room, I found my father with his chest blown apart and his arms spread out in a sea of blood, as if he were swimming toward a shore only he could glimpse. In the midst of this world in collapse, my brother, Roland, remained seated in his room, the gun resting in his lap.

Don’t touch me, he ordered, strangely calm. Never touch me again. You’ll burn.

That’s how he stayed, motionless, until relatives and neighbors burst into the house, panicking and shouting. From the window, I watched my brother being taken away by the police. There was no doubt about it: It was he who had shot our father, the respected hunter Henry Bullseye. An accident that our mother had already seen coming:

Firearms in the house only bring tragedy.

That was what Martina Bullseye used to say. On the day my father died, my mother was no longer there to witness her premonition. She had died some weeks before. A strange illness had consumed her in a trice. So at the tender age of ten—and in the space of a month—I became an orphan. And I was to be separated forever from my brother, Roland. As he was an adolescent, he was spared a police investigation. He was cleaning the gun, just as he often did, having been taught to do so by his father. And so they decided to take him to a psychiatric hospital. They say he never uttered another word; never again did he behave like a person. Roland was goodness incarnate but his mind was eclipsed, consumed by guilt. In the night sky of my mother’s story, my brother joined the stars that had been swallowed up by the darkness.

*

My father was a man who filled the world—his foot would cross the threshold and we would feel the steadiness of his weight, as if we were in a little boat. What he did in life was far more than an occupation: Our father, the esteemed Henry Bullseye, was a hunter who was in great demand, and when he went away, he left our house full of sighs and mysteries. A tall, austere man, he was little given to talking. If I’d been cared for by him alone, I might never have learned to speak. My mother provided relief from this introverted side to my father: He was an emigrant from the mountains of Manica, where he had grown up among escarpments and rock faces. We would often hear his nostalgic yearning:

Where I was born, there’s more earth than there is sky.

Maybe because he was from another tribe, Henry Bullseye chose a mulatto woman for a wife. At that time, it wasn’t common for a black man to marry a woman from another race. The marriage made him even more solitary, driven out by blacks and excluded by whites and mulattoes. In fact, I only understood my old man when I became a hunter. My father was a stranger in his own world.

*

The receptionist at the newspaper offices is a fat woman, unhurried in speech and gesture. She seems to have been born like that, sitting, her backside like a planet competing with the Earth.

I’ve come to find out about the result of the contest.

I wave the clipping of the advertisement in front of the glass partition. The receptionist’s shrill voice was made to seep out through the gaps in the broken glass:

Are you the hunter in person?

I’m the last of the hunters. And this is my last hunt.

The woman gazes up at the ceiling like an astronomer gazing up at the noonday sky. She opens an envelope in front of me, while I start talking again excitedly. She clearly wants to bide her time disclosing the result.

I don’t know why they published the advertisement. There aren’t any hunters anymore. There are people out there firing their guns. But they’re not hunters. They’re killers, every single one of them. And I’m the only hunter left.

Archangel Bullseye? Is that your name?

I’m the only one left, I repeat without answering her question. And I continue my feverish discourse. Soon, I assert, there won’t be any animals left. For these false hunters spare neither the young nor pregnant females, they don’t respect the closed season, they invade parks and reserves. Powerful people provide them with arms and whatever else they need.

It’s all meat, it’s all nhama, I say with a sigh, despondent.

Only then do I look again at the fat woman’s expressionless eyes, as she waits for my disquisition to end.

Is your name Archangel Bullseye? Well, you’re going to be able to hunt

to your heart’s content, you won the contest.

Can I come into your office? I want to give you a kiss.

With unexpected agility, the woman gets up, leans across the counter, and waits, her eyes closed, as if my kiss were the only prize she had won in her whole life.

Mia Couto, born in Beira, Mozambique, in 1955, is one of the most prominent writers in Portuguese-speaking Africa. After studying medicine and biology in Maputo, he worked as a journalist and headed several Mozambican national newspapers and magazines. Couto has been awarded several important literary prizes, including the 2014 Neustadt International Prize for Literature, the Premio Camões (the most prestigious Portuguese-language award), the Prémio Vergílio Ferreira, the Prémio União Latina de Literaturas Românicas, and others. He lives in Maputo, where he works as a biologist.

David Brookshaw was born in London. He is Professor of Luso-Brazilian Studies at Bristol University, UK, with a specialist interest in postcolonial literatures in Portuguese, comparative literature, and literary translation. He has translated a number of books by Mia Couto.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

His English: On Joseph Brodsky’s Self-Translations, by Ann Kjellberg

Jonathan Franzen’s First Words on Purity

Our stories from National Short Story Month, “The Geranium,” by Flannery O’Connor, “Monument, by Amelia Gray, and “Resort Tik Tok, by Arthur Bradford