I met with Richard Howard on a bright October morning in his apartment near Washington Square Park. He welcomed me as he always does, standing on the threshold, one foot in, one foot out, watching me walk down the corridor with a smile on his face. We kissed hello à la française. On that Saturday morning, he wore a striped shirt of subtle shades of blue and elegant black trousers. His round glasses, of which he owns an astonishing collection (same model, in a Pantone-like array of colors) were deep blue, matching the darkest of his shirt’s stripes. His socks, light blue, matched the other shade. The walls in Richard Howard’s home are lined with books, from floor to ceiling, dimming the place with an opaque silence. Behind me, as I sat on the sofa, battered editions of Cioran, Gide, Baudelaire in the original—authors whose works Richard Howard translated or taught. Roland Barthes was one of them, as well as a longtime friend.

-Marion Duvert, Editor and Associate Director of Foreign Rights

Duvert: Samuel Beckett once wrote that there was no need of a story. Roland Barthes would have probably agreed with that, and yet I think I would like to hear it—the story of you and Barthes. How did you come to meet him? Did you meet the man first, and then the work? Or the work first, and then the man?

Richard Howard: I didn’t know the work at the time. He had published two books in France, but nothing had been translated. I was here in New York and the phone rang, and it was him up in Massachusetts, or one of those summer schools where he was teaching. He had heard of me—I don’t remember how. I don’t think he had ever heard of me as a teacher, or a reviewer, or anything like that—or even as a poet, I don’t think so.

But he had heard of me, and he knew no one in America, and he knew that I spoke French.

So he called because he had arrived, he was settled in, he was teaching a course, in French, I guess. He knew nobody—even the students in his class. (Roland, as I was to discover, was a very shy person.) So he called me just to say hello, and say that he would like to come to New York, and could I show him around a little bit because he had never been here.

I said certainly, and that I looked forward to it very much. He arrived. He had the first copy of, I think, Mythologies in print. The first day was very proper and careful. But we got along very well. It was apparent that he had made the right choice, and that we were going to be friends. I suppose that means I met the man first. But he came carrying a book, and I think he knew that I was a translator; and he wanted me to see it. I did translate right away three or four of those pieces that were published in various periodicals here. That was the beginning.

I don’t think he ever again read any of my translations [of him]. I don’t think he had any . . . it isn’t that he didn’t have interest. He would say that he didn’t know English well enough to have it make any difference; it was just his satisfaction that they were in English. At the beginning I think there was some interest in that fact, but I never heard from him again on that subject.

I would ask him questions. I remember calling him up once and saying that he had referred to somebody inadequately or incorrectly, as I just knew. Did he want me to silently correct the mistake? He said, “Oh, of course. Do whatever you want. I have no idea.” And then there was some question of some king or even Egyptian pharaoh, and he said, “Well, make it up. Make it up. I don’t remember the case myself. If it’s not correct in the French text, just make up something.” He had decided that I was trustworthy, and he could rely on me to take care of such things, and there was no further discussion about it. He was not an anxious author about his translations.

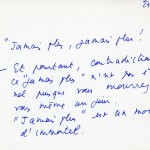

- 27 Octobre

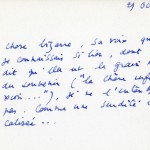

- 29 Octobre

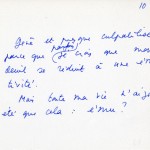

- 10 Novembre

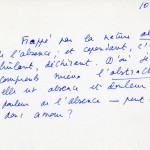

- 10 Novembre (2)

Duvert: It must have been wonderful, to be so fully trusted. This leads me to thinking about Mourning Diary. It is a very intimate book—not only because it displays a degree of emotion that was rarely, if ever, displayed in Barthes’s other books but also because it constantly refers to Barthes’s intimate world, his friends, his thoughts, his obsessions and griefs. It must a challenge for a translator, to read through so many hints and allusions. Did knowing Barthes well help in the process of translating his diary?

Howard: It must have. But I never thought of it because, for a translator, everything, even the most formal work—or the most intimate—is always the same: everything is intimate, everything is formal: both are true. The question of the dimension of intimacy for any text, when you are translating it, has nothing to do with whether or not you knew the person, whether you knew him better or worse. I don’t think so. That’s entirely related to one’s conscience and talent as a translator, and it has nothing to do with my affection for or cognizance of Barthes. Though I think I might have felt, “Yes, I see: there are things here I recognize and can connect with other things that I have already made up words for.” I could use that in this instance. But it was merely a translator’s problem, not a friend’s problem or an intimate’s problem. Or one might say the translator’s problem is always the intimate’s problem.

Duvert: But beyond that, and for a book other than Mourning Diary—for a book of classic prose—wouldn’t the fact of knowing an author personally and being good friends be a little stifling for a translator? To translate well, one often has to be allowed the freedom to take a slight step away from the original—a necessary adjustment, a necessary betrayal to convey the work in English with talent and style. Wouldn’t the fact of knowing and cherishing the author make it more complicated?

Howard: No, because I knew already that Roland had passed that stage of even being interested in me as a translator. We were good friends. I loved asking him questions about French literature because my awareness of it was so different from his, and so inferior. So I got a lot from him.

I can remember an important moment when we were walking around in New York, and I said, “You know, I’ve come to a certain point”—I was in my early forties, so it was many years ago—”and I feel that I’ve sort of gathered together or gained some sense of what French literature is. I think I’m familiar with the monuments, and even some of the underground monuments. But is there something that you feel, knowing me, and in relation to the things we say, that I simply not only have left out but am ignorant of? What is it that I’m missing?”

He looked around, he said, “Well, of course, Richard. It seems to me that you would be interested in the work of Gaston Bachelard.” And I said, “Yes, I would. But I’ve never heard of him, I’m afraid.” He laughed because, in his world, that was really a vast number of books. He was a scientist, but a kind of poet-scientist.

I would call him up in France, when I was translating, and say, “What is this? I don’t understand it. Can you help me?”

“Of course,” he’d reply. Wonderful to have a living author who is there, who can do that for you, as a translator. I frequently, in translating works by dead authors, am simply stuck, and have to cast my net far and wide to find out exactly what it is, and often—sometimes—do not find out, and have to make up something else, or cover it over in some way. In the case of Roland, I don’t think I performed with that kind of inadequacy because he was there, and I could call him. And I feel, ever since his death, I feel—not that I’m inadequate for the work but that it’s a resource that I lack now; and it’s a terrible thing for me, to suddenly feel, “Oh, I’ll just call Roland; ask him what to do.” And I can’t. That’s a terrible thing.

Duvert: I find it very interesting that you started your career as a lexicographer. In the case of Barthes, who coined words, I imagine that you had to make up words to transpose his inventions. How you would do that? Would you talk to him? Was it easy to find an equivalent? I don’t know if you have a few examples, off the top of your head, of your favorite coined words. But for instance, in Mourning Diary, there is a verb that does not per se exist in French, se gregariser, which means “enter into a whole,” and which we translated as to gregoriate.

Duvert: I find it very interesting that you started your career as a lexicographer. In the case of Barthes, who coined words, I imagine that you had to make up words to transpose his inventions. How you would do that? Would you talk to him? Was it easy to find an equivalent? I don’t know if you have a few examples, off the top of your head, of your favorite coined words. But for instance, in Mourning Diary, there is a verb that does not per se exist in French, se gregariser, which means “enter into a whole,” and which we translated as to gregoriate.

Howard: It would have something to do with enabling the reader in English to recognize the whole notion of gregar, and gregarious, and so forth: those words which we have in English, even though we don’t have such a word. But, ordinarily, Roland’s words—the words that he coined or made up—were with Greek roots, and they could be reproduced in English with Greek roots in the same way. The roots were the same. They were roots, and they flowered in English one way and in French another. In many cases, they were even easier to translate into English than they had been for Roland to make up in French.

Many people objected to Roland’s language in French because of those words. Partly because they were already translated by me from Roland in English—that was one reason to accept them. Another was it was possible, sometimes, to find English equivalents for the actual words from Greek roots that were within reach of English. I don’t recall the words now, but I remember that there were times when no one would question the words, even though they were not English and they were not Greek.

Duvert: That’s really interesting to me, as someone who read Barthes in the French of course. It’s true that it was and it remains notorious: there is an aura of difficulty around Barthes in France. It mostly has to do with his inventions, yes, although his style is in truth much more approachable than other French theorists’. It’s great to hear that his inventions aren’t considered as much “out there” in English—the wonders of translation, I suppose. Speaking of which, I wanted us to focus on one entry of the diary that I love. It is beautiful and moving in French, and all the more so in English. The entry is dated June 15, roughly a year and eight months after Barthes’s mother passed away. It reads in French:

Tout recommençait aussitôt: arrivées de manuscrits, demandes, histoires des uns et des autres et, chacun poussant devant lui, impitoyablement, sa petite demande (d’amour, de reconnaissance): à peine eut-elle disparu, le monde m’assourdit de: ça continue.

And in English:

Everything began all over again immediately: arrival of manuscripts, requests, people’s stories, each person mercilessly pushing ahead his own little demand (for love, for gratitude): no sooner has she departed than the world deafens me with its continuance.

I’d like to talk about the last stretch of the sentence. I find the English word continuance beautiful. Do you would recall the strategy, the process that led you to this transposition? In French we have ça continue in italics. We have continuance in italics, too, in English.

Howard: The two versions, the French and the English, are italicized for different reasons. In French, they are italicized because that is a kind of manner of speaking, which is really not quite proper. It’s from a realm of discourse which is more intimate, and more informal. Ça continue.

I was not comfortable with translating it that way. It would have had, the world deafens me with. And then it would be, it keeps going on, or something like that. That’s very much what the French is. I just felt that it was not a moment where I could lapse into the colloquial, that I wanted some kind of conclusion to the sentence and the observation. So I said, No sooner had she departed; then, the world deafens me with; and then, its; and then all those things which in French mean ça continue, “it keeps going on” or “it continues.” So I just came up with the noun continuance, which is not a frequently used word in English, though available to anybody: one understands what it means. I felt that was it, the world deafens me with its continuance. I wanted to say with its continuance rather than by its continuance because it’s the material that’s been referred to in the rest of the little passage that has to do with the continuing. You have to say it’s not by its continuance, in the sense of “the world’s continuance,” but with its continuance because it wasn’t the world that was continuing but all these things: the people’s stories, the people pushing ahead their own little demands for love, for gratitude, and so forth; and so it was with all that that the world deafens me. I wanted to get that.

So I think that was why I did it, if I remember—or at least in making it up according to my method. But I don’t really have a method; I think translators have to invent constantly in their method, as they go along. They can’t have a system, or else the work comes out systematically, and that’s not what you want.

Duvert: Let’s end on this notion of continuance, shall we? Thank you.

See also:

Hill & Wang will be hosting two Roland Barthes events in New York City.

October 19th Launch event with remarks by Richard Howard, Judith Thurman, and Wayne Koestenbaum. Clic Gallery, 255 Centre St., 6-8 PM (Facebook Invite | Clic Gallery | RSVP appreciated)

November 8th n+1 Symposium on Roland Barthes: Reflections on the Public, Private Intellectual. Richard Howard in conversation with Marco Roth. The Kitchen, 512 W. 19th St.. 7 PM (More Info)