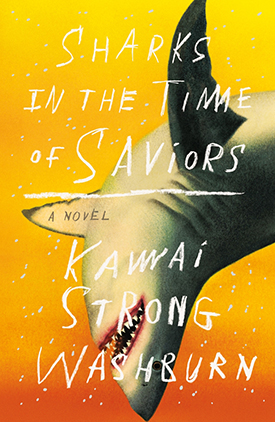

Sharks in the Time of Saviors is a groundbreaking debut novel that folds the legends of Hawaiian gods into an engrossing family saga; a story of exile and the pursuit of salvation from debut author Kawai Strong Washburn. In this interview, transcribed from a virtual event hosted by Next Chapter Booksellers, Washburn and Marlon James (Black Leopard, Red Wolf) talk about images that haunt us, the relationship between the mythical and the mundane, writing about where we’re from, and Sharks in the Time of Saviors.

Marlon James: I have a bunch of questions. I hear you have some questions for me, but probably not as many as I have for you. It’s such an honor to do this and I think your novel is so sensational. And I remember when your editor—Sean is your editor, right? Because Sean was my first editor as well, and I remember when he told me about this book. And if you know Sean, Sean’s “it’s pretty good” is everyone else’s screaming from the mountaintop. So, he was like, “it’s really, really good. I really think you should read it,” and I was like wow, Sean, that’s like a Sean McDonald equivalent of hyperventilating. It’s incredible.

In one of your interviews you talk about the image of the shark with a child in its mouth as something that was haunting you before you even had a book. This also serves to get the writing process question out of the way—is that a part of your writing process? An image shows and you’re not sure what it is and writing is some way of interpreting it, or…?

Kawai Strong Washburn: I think it varies from project to project. Things happen differently. Sometimes I think I have an itch I need to scratch, about some sort of concept. Maybe I’m thinking about memory and grief and I want to write something to figure out what that thing is. And sometimes it’s an image. In the case of this novel, the image had been in my head and I hadn’t thought much of it at the time, but it kept coming back. It just stayed there somewhere in my subconscious and for whatever reason my mind kept engaging with it. So, I finally sat down and thought, well, what is this? If there’s a shark and it’s carrying a child out of the water, who is the child? Does the child have a family? Why was this child in the water? There’s a whole bunch of questions. I started playing with those and it seemed like there was something interesting there.

MJ: I think sometimes with fiction, you’re actually doing detective work. Especially if it begins with an image. It also sometimes begins with a character for me. It’s sort of like, who are you and why are you in my head and why won’t you leave and what’s your story about? I wondered if that had anything to do with the novel as a series of first-person narrators. How did that come about?

KW: It did come out after that image happened and there was a child. When I think about children, often I want to know about their family. I think we often think about children in the context of family, fairly or unfairly. So, I started thinking about the family and asking questions. And I started playing with it a little bit. I tried a little bit of it in third person, and this happens often when I’m starting, especially if I’m working on a novel—this is the same thing I’m going through now—I try different perspectives until I see what feels like it is appropriate for the material. When I started writing Dean’s chapter in first person—that was when I settled on the first-person perspective. I think at the time, I can’t remember what draft I was on, but A Brief History of Seven Killings, which I loved, came out while I was writing Sharks in the Time of Saviors. And one of the things I love about that book is the way move through a bunch of different voices. I like getting hypnotized into the worlds of all these different characters and feeling my consciousness transform into their consciousness. When I wrote Dean’s chapter, something just hit and stuck. I was like, I want to write this, and I want to write it for all the characters. And A Brief History of Seven Killings gave me hope that maybe I could make it something that would be fun, so.

MJ: Yeah, it’s funny, we talk about writing novels in the voice of the character, and some of your characters speak also in a Hawaiian Pidgin, reclaiming the voice. It was a huge struggle for me, that the voices that my characters speak and the voices that my narrator speaks could be anything close to the voice that comes out of my own mouth. And that was years of struggle for me. I don’t know how much of it was for you, in terms of language.

KW: It was so hard, it was so hard. I think I wouldn’t have done it if I’d known how hard it was going to be. But I started, and I really enjoyed it. There’s something that I really enjoy in the first-person narrative. A really well-written first person narrative, I don’t feel the same after it’s over; those voices stay with me. The consciousness that I’ve sort of interacted with, it never goes away for me. Novels that really work in first person, I feel like I’m a bigger thing when I’m done reading them. So, I really wanted to try that. But, man, was it hard. It’s like I had to invent these voices and these psyches and I had to constantly interrogate the grammar and the metaphors and every little bit about the way that they express a thought. That’s just so much work. Every time I wrote something that sounded like me, I was like, “nope,” cut it out, that’s me. I gotta do it the way Kaui would do it. How would Kaui think about that? Not how would Kawai think about it.

MJ: That’s so funny. The two challenges: one, everybody sounds the same; two, everybody sounds like me. I remember I had to almost create dictionaries for each character at some point. Particularly the Americans. Like, an American in the 1980s can’t sound like an American in the 1970s, and all of that. But I wonder, is there something more trustworthy about first-person narration? About having the characters tell their own stories?

KW: I think people expect that. That’s funny that you ask that. It’s one of the things that’s fun about a first-person narrator. It doesn’t even have to be a first-person narrator, but when you can make an untrustworthy narrator, some people will love it, because it catches them off guard. I think we have this tendency to believe the narrator. And when it’s in first person it’s very intimate, right? So, you’re like, oh, this must be the truth, the thing they’re telling me must be the truth.

MJ: It reminds me of Notes on a Scandal by Zoe Heller, a novel that thoroughly betrays the first-person narration. Spoiler alert—you pay a price for believing that narrator.

KW: Yeah, one of the ones that did that for me was Teju Cole’s Open City. I think in the last three pages you’re like, “wait, what?”

MJ: You know, people are going to call this novel magical realist. I don’t necessarily think that it’s a slur any more than it’s a compliment. I think it just is what it is. But I remember, I think one of the reasons Márquez kind of rejected the term, is that he said, “No, this is real.” I feel that way about writing the Caribbean as well. I feel that writing about Jamaica—I’m not writing fantastical shit. If you really want to understand how this family and how this country got to be that way, it has to open with sharks. Can you tell me about the relationship between the mythical and the mundane in this book? Is it magical realism, or is it just something else?

KW: Right, yeah, the way you described it is the exact same way it felt to me when I was writing this. I knew I had to find a way to write it so that it didn’t feel so surrealist or supernatural that people would start to think of it as fantasy, or that it would lose some of the impact or veracity that one might get from the characters. I wanted it to straddle that in a way that doesn’t make people think all of a sudden, “oh, everything here’s make-believe.” But that’s just part of growing up there, man. Me and my friends would tell each other ghost stories about things like the night-marchers. People in Hawai’i still talk about the night-marchers today. And the gods, like Pele, who is the goddess of fire and volcanoes. It’s something that you feel very viscerally there. People aren’t messing around when they talk about Pele, it’s not a little tale. Whether Pele is personified or not, she is a force that is a part of the natural world there which we feel is a part of our lives. And that’s where a lot of that comes from. It was a challenge balancing these elements to make sure I didn’t go so far that people found the story unbelievable, but I wanted you to feel like it is just a real thing and not a magic thing.

MJ:The other thing about it too, to keep again the comparison to Márquez, which I think sometimes people misunderstand with Márquez, is that magical things—and I really don’t want to use that word, but, let’s use it, the supernatural, the out-of-the-ordinary—one of the things that happens in this novel and happens in Márquez’s stories is that it also immediately impacts the community. So, I’m going to get the pronunciation of his name wrong . . .

KW: Is it Nainoa?

MJ: Yes, Nainoa. So, immediately they start to monetize the miracle, and on one hand you can say that they’re exploiting it, but on the other hand, it becomes something that directly impacts the community with social and political consequences. It’s not just weird shit happening for the sake of weird shit. I was thinking you can talk about that. The thing that struck me is that this is what happens. If a statue of Mary cries tomorrow, it’s going to impact the whole community, the economy, the society, and so on. If you talk about that whole, instead of it being some weird sort of event, it galvanizes a lot of things. It throws characters on all these courses, some of them tragic.

KW: Yeah. And I think that that’s part of it. Early on in the first draft it hadn’t quite gone that direction. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized—well, first of all, poverty—I think it’s easy when you have privilege and safety, and you have money, it’s easy to start talking about money in this really abstract way, and to say things about wealth and convenience as these things that are sort of affectations. When you are living in poverty, of course you want money, and of course you need it—that is the barrier between you and safety and security and comfort. And so, for this family that is so close to the edge of poverty, if they have this moment where they have a child that suddenly the community has an interest in, that the community sees as something of value, these parents—they’re making choices about their family. If this can help us, then why not? Why would we not do that? The idea that they’re going to set this aside as some sort of noble or spiritual value, but not something that could be of economic value for them, is unrealistic. And you point to some of the places where you can see this play out, places where there’s a moment of something bigger than the everyday occurrence, and if it’s something that the community can extract value from in a way that feels to them like it gives them things they need, that’s going to happen. For this family, that’s what happened. It was also a way for me to talk about America. I tried to bring that up in a few places in the novel, just in the sense of like, what doesn’t talk if it isn’t money in America, right? That’s in front of your face. You’re going to need money. And you’re going to take any chance you get to make it.

MJ: Whether it’s America or so on, it’s that people who don’t have many things of value recognize something of value. And exploiting that is going to have consequences. Because the thing also about this novel is, a lot of it is not otherworldly or mystical—it’s people just trying to deal. In a lot of ways, it’s like, what do you do when you have an extraordinary sibling? And it actually pulls a lot of the characters apart. Which character was the hardest to write? I’m assuming none were easy.

KW: None were easy. The two that were hardest—Nainoa was hard because in an early draft, someone had read it and they were like, “I really don’t like him.” And that was because the way I had written him, he was very arrogant and privileged, which to me felt really real because I was like, if he is a kid, then he becomes this big deal when he’s like seven or eight or something—I can’t remember his exact age now—when he has this event and he suddenly has all this attention heaped on him, when you’re that young of course you’re going to take some level of privilege, and be kind of a snotty brat about it and all that. It’s really hard not to when you’re a kid, because you’re self-centered and you don’t have the kind of fully formed psyche that might at least pretend to be humble. So, he was very arrogant and privileged, and people were like, “man, he’s kind of a smartass. I don’t like him very much.” I tried to keep some of that, which I think is real, as an aspect of Nainoa. If you’re in a situation where you’re young and you’re gifted, even if you’re gifted at math or sports or whatever, you end up being kind of bratty. I needed to try and preserve that but also have him be someone a little bit more sympathetic. And everybody has their blind spots. So, trying to write him so that he’s arrogant without realizing he’s arrogant, but also having him be sympathetic in a way—I really struggled with that; it was hard. So, Nainoa was the hardest to write.

And Dean is just so entirely unlike me in every way possible. He’s the kind of person that probably would have beat me up in high school. I challenged myself to have him be a character that did lots of things that made me uncomfortable, that I didn’t like. Inhabiting that psyche was sometimes hard on the page, because he says things that are mildly racist, he says things that are homophobic—he’s just this character that is on one level everything that is not me. But then on another level he has his moments in which he expresses true love for his family and loyalty and redemption and all those things. So, getting that right with him, as well, was pretty challenging. They were the two hardest characters.

MJ:And that leaves us with Kaui. Kaui literally tries to escape Hawaiian-ness. I’ve realized with a lot of fiction that we’ve seen—whether it’s yours or Tommy Orange’s or Kiran Desai’s, or so on—characters trying to escape their, for lack of a better word, their national identity, or whatever that might mean—their Hawaiian-ness, their Indian-ness, or their Jamaican-ness. What do you think is behind that? What’s at the core of that? And is that something you felt yourself doing?

KW: Good question. I think I was exploring that in the novel and it was probably . . . This was an interesting novel; it ended up being a novel of self-exploration for me in a way that I didn’t expect until I was in the later stages of it. I was in the second or third draft when there were all of these parts of me that were on the page that I didn’t expect to be there. And I think that it’s a combination of two things. On the one level, I think that when you feel your otherness, at least for me—when you can feel your otherness in a place, and especially when you’re younger, I think that there’s a very natural tendency to break free of that. And it can be for multiple reasons. Sometimes people think that that’s an asset, or they put you on a pedestal, or they view you through some sort of special lens because you’re from a different place to which they ascribe all these things. You can feel that on you, and you want to avoid that, and you don’t want that to be attached to you. You want people to evaluate you as a person, not as a part of these bigger ideas they have about where you’re from. But then, there’s also another side of it, where you’re worried about how it could have a negative connotation on you as a person, and people could take that as a negative thing. So, you’re trying to escape the outside world’s view of you and trying to find some way to define yourself that isn’t attached to these things that feel like they have weight. It’s certainly something that I’ve dealt with, but I didn’t realize until I was writing this that it was something that was as much a part of my life as it was. I wanted to explore that. I think it’s something a lot of people don’t understand about the islands. And when I’m speaking about the islands I’m talking specifically about Hawai’i. I don’t think a lot of people think about it that way, but that’s just because they’re not from there. People often ask, “What are you?” And I’m always like, “Oh, here’s that question again.” Or people will ask, “Oh, you’re from Hawai’i—why did you leave?” And all that sort of stuff.

MJ: They see tourism pictures of Jamaica, and they’re like, “Wow, why did you leave?” And I’m like, for the same reason you don’t live in Vermont anymore!

KW: Exactly! A lot of people want to leave the place that they grew up in; it doesn’t necessarily mean they hate the place. People want to experience other things.

MJ: But it’s not just the place, it’s also what the place comes to represent. Because I thought with Kaui that in some ways Hawai’i is not just Hawai’i; Hawai’i is also family, and family is complicated. I was reading, I think it was a Vanity Fair article or maybe somewhere else, where you talk about a defense of genre fiction. And I was curious about that.

KW: I came to literature through genre. That’s where I started reading. I loved science fiction and fantasy; that’s where I did all my early reading. I hadn’t touched anything that was non-genre. You know, I hate the term, but I hadn’t touched anything that wasn’t in that mode until I was probably in high school. I think that was the first time I read something that wasn’t in one of those genres. I think when the term fails, when people use “genre” as a pejorative, is when the idea that is being played with by the author consumes the inner lives of the characters in a way that makes all the characters feel like they’re just pieces being moved around to play with this bigger idea. And that’s when a lot of people who want to read a story that is more than just the plot or the things moving around start to say, “Oh, well this is genre,” or some inferior form of writing. But I wanted to pull all the things I love about genre together with the things I love about literary fiction. There’s stuff you can read that’s purely literary that’s just like, some disaffected person walking around, I don’t know, Brooklyn or something. It’s like, I get it!

MJ: Because you spent some time writing this novel, at what point did you think you had a novel? What was the turning point for you?

KW: I haven’t been to get an MFA. I didn’t have any other friends that were writers. And I was just sort of having to flail around in the dark, reading craft books . . .

MJ: Which craft books?

KW: It’s hard to remember. I think a couple of the ones that I came into early that seemed like they had something that really stuck with me—there was one that was called The Making of a Story.

MJ: I know that book! Yeah, I remember that. The pre-MFA days when you just grabbed any book you could find.

KW: Yeah, that was one of them. I stumbled on John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction. And I think that Stephen King’s was one I came to early as well? There were a couple of others; those are the ones that pop into my head.

Anyway, I had been doing that kind of flailing around in the dark—I would go through a draft, and then I would put it away for six months. I didn’t have anyone to give it to, so I would just be like, well, I have get away from this wreck of pages for a while and come back to it with fresh eyes. I had done that for a second or third time and still thought something was there. I would keep coming back to it and I would be like, this sucks, but I want to fix it. And then I would do that again. And that was when I was like, okay, if I keep coming back to this after six months, and it’s not absolute garbage, then I think there’s something worth trying to keep here. Then let’s do it; let’s make this thing happen. And after that happened I think the second or third time I was really like, this is a novel. I can make this into a novel.

MJ: What were you reading at the time?

KW: Oh, man. This book took me ten years to write, so all kinds of stuff. A lot of stuff. I loved reading poetry, and so there’s poetry that still sticks out in my head. There was a poem by Nate Johnson that I found on the poets.org website—they have a daily poetry thing—called “Praise Song.” It’s a scene poem about the narrator and four of his friends, and they’re all Black and they’re together in this place in which their privilege—because some of them have money and some of them don’t—is butting up against them and there’s a fight. But the rhythm and the lyricism and all of it is beautiful, and I still keep it in my head. I remember that showed up somewhere in the middle of, like, my third draft, and it helped me figure out how I wanted to structure the rhythm of Dean’s voice. It cracked open some thoughts I had about his inner life. And, like I said, A Brief History of Seven Killings—I can’t remember how far along I was, I was probably in the tail end of it, but mostly it just gave me hope, because I was worried no one was going to read my book, because at that point there was a lot of pidgin, the patois was in there.

MJ: I didn’t know what I was doing when I wrote that book. I didn’t have control over it, but I think at some point starting with that novel I had to let go of all the things I thought a novel was, for one thing. After a while I finally found a way around doing it, because I really was fighting against the idea of writing a novel in dialect; I thought, I’ll just leave it until my editor takes it out. And he didn’t really take anything out.

I was reading poetry as well. I find that reading poetry and drama, particularly—

KW: I don’t do that enough.

MJ: I didn’t realize until an author asked me in an interview, what is my debt to Greek tragedy. I was like, “I don’t—oh, crap.” I actually do read Greek stuff, Greek tragedy, almost before I write every book.

KW: That’s so funny. I read the Iliad somewhere in the later stages of this, but not a lot of the classics during this novel. And I’m still really bad; I haven’t read as many as I should have.

MJ: Eh, just read the Oresteia.

KW: But there’s so much out there that I haven’t read. I’m probably a really unsophisticated reader. I think a lot of people would be unimpressed if they drilled me on some of the great works of western literature that are in the canon, because a lot of times I pick those up and I really have to work at them. And sometimes I’m just like, there’s other stuff out there that resonates, like Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son, Jesmyn Ward’s Salvage the Bones—that was another one that I had read early on; Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street, which I think I gave credit to in the acknowledgements, as well. But those are some of the works to me that rang my bell in a way that a lot of the stuff like The Great Gatsby or Chekhov or something—they just didn’t quite ring my bell the same way that some of that stuff did. And so, I’ve had a hard time dipping into some of the big works of the Western canon, because a lot of times it just feels like, for whatever reason, it’s still work for me.

MJ: I go back and forth with some of them. I sometimes think it depends on when you read them. One thing that I’m loving right now is Mary Shelley’s The Last Man. It is total goth. But it’s the first dystopian novel, and what is it about? The last person surviving a plague. That’s what I’m reading right now. And I’ve been telling people that are like, “I can’t understand this administration, I can’t understand the politics”—that’s ’cause you haven’t read Moby-Dick. You want to understand 2020? The only way you’re going to understand it is if you read Moby-Dick. Then you’ll understand.

KW: A few of the questions I had for you actually came up over the course of us talking about this, and one of those was the sort of things you read while you’re writing, or if you read at all, or what things.

MJ: I read a lot; it’s not just poetry. For one, I create these sort of reading libraries for each book I’m writing. Some purely for research, of course, because most of the stuff I write tends to be historical or fantasy, speculative. Certain books because they intimidate the crap out of me and I just want something like it. For me that book is Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel. I was supposed to interview her a few weeks ago, and then Covid happened, and I’m very distraught, because she’s one of my big, big, biggest literary heroes. And I think Wolf Hall is a perfect novel.

KW: Man, I gotta read this novel; everybody loves it. Or at least most people I know.

MJ: It’s a phenomenal book. We were talking about first-person earlier and the way in which we invest in a story when it’s being narrated by someone. And I read this novel As Meat Loves Salt. The writer’s Maria McCann; it was her first novel. That was the first novel in years that I threw across the room. More than once. There was a scene in that novel where I went, I can’t read this. I cannot follow this character when he does this. Nope. And then within a week I continued reading. It was the first novel in years I’d wake up in the night fretting over a character. I’d be like, I don’t know what’s going to happen to him! I just fell hard for this character, and the character’s a total sociopath! But again, it’s that thing that can happen with first person.

Kawai Strong Washburn was born and raised on the Hamakua coast of the Big Island of Hawai‘i. His work has appeared in Best American Nonrequired Reading, McSweeney’s, and Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading, among other outlets. He was a 2015 Tin House Summer Scholar and 2015 Bread Loaf work-study scholar. Today, he lives with his wife and daughters in Minneapolis. Sharks in the Time of Saviors is his first novel.

Marlon James was born in Jamaica in 1970. He is the author of the New York Times-bestseller Black Leopard, Red Wolf, which was a finalist for the National Book Award for fiction in 2019. His novel A Brief History of Seven Killings won the 2015 Man Booker Prize. It was also a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and won the OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature for fiction, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for fiction, and the Minnesota Book Award. It was also a New York Times Notable Book. James is also the author of The Book of Night Women, which won the 2010 Dayton Literary Peace Prize and the Minnesota Book Award, and was a finalist for the 2010 National Book Critics Circle Award in fiction and an NAACP Image Award. His first novel, John Crow’s Devil, was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for first fiction and the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, and was a New York Times Editors’ Choice. James divides his time between Minnesota and New York.