Some places draw language to the surface. The surroundings (that lovely word) provoke a response, sometimes through the sheer subtlety of the landscape’s character. As I wrote ten years ago in “The Rough Bounds,” “I like the sort of track that passes / out of English altogether.” If you ask why, it’s a matter of appetite. I want to distill the experience into words, the way whiskey distills the atmosphere, so that we might sip the peat-reek and weather. In his poem, “To Introduce the Landscape” (Allen Curnow: Collected Poems, Auckland University Press, 2018), the New Zealand poet Allen Curnow wisely warns against this sort of enterprise, with some mockery of the ways it usually gets attempted:

To introduce the landscape to the language

Here on the spot, say that it can’t be done

By kindness or mirrors or by talking slang

With a coast accent. Sputter your pieces one

By one like wet matches you scrape and drop:

No self-staled poet can hold a candle to

The light he stares by.

And yet Curnow, like the rest of us, keeps on striking matches against the sun. We feel an affinity for certain spots, in all their moods and variations; and in such places, we discover a reciprocity between outer and inner states.

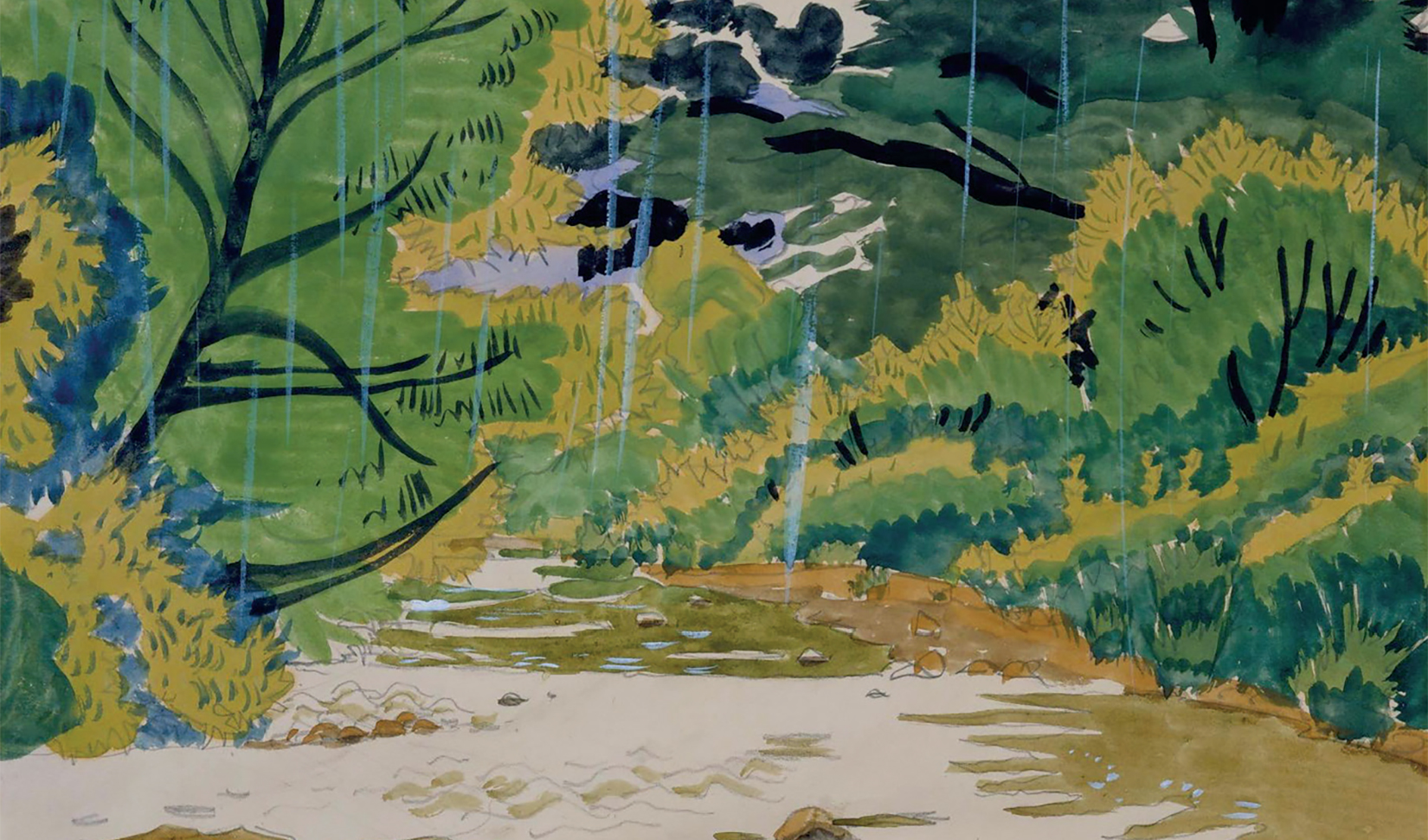

Pickle Creek is such a place, an hour south of St. Louis. It’s a little sandstone canyon, with gneiss and granite outcroppings, the creek tea-colored with a sandy bottom, full of minnows, darters, shiners. Along the banks are oaks, with pines and dogwoods in the understory, the trees full of warblers in the right seasons. The banks themselves are covered in ferns, as well as mosses and lichens due to the acidic soils. It’s a dense and damp landscape, without clear horizons. I’ve spent a good deal of energy putting myself in open spaces, the rolling swells of an inland sea, a treeless moor or windswept plain. But I’ve always lived closer to places such as Pickle Creek, places that don’t inspire ecstasy, but a quiet buzzing energy. And then, I tend to live without clear horizons or ambitions, prone to a great deal of mulching.

The mosses and lichens have caught my interest in recent years, as when I was younger I moved too quickly to study and learn them. But as I soon discovered, searching through field guides, this impatience applies to humans more generally: most lichen and mosses have no common names, never having been called on to do anything for us. The distinction between varieties—with a few exceptions—simply hasn’t pertained to us. This recognition had two implications. First, we have a sense of “wild” as demonstrative and unconstrained. But the wild can also be defined in terms of reticence and subtlety. It escapes us, not by muscular effort, but through a refined irrelevance to our concerns. Second, if my interests have shifted over the years from large mammals to songbirds to mosses and lichens, maybe I’m getting old! When I turned to John Ruskin, I found that he had arrived at both these recognitions before me, in his Proserpina: Studies of Wayside Flower:

It is mortifying enough to write,—but I think thus much ought to be written,—concerning myself, as ‘the author of Modern Painters.’ In three months I shall be fifty years old: and I don’t at this hour—ten o’clock in the morning of the two hundred and sixty-eighth day of my forty-ninth year—know what ‘moss’ is.

There is nothing I have more intended to know—some day or other. But the moss ‘would always be there’; and then it was so beautiful, and so difficult to examine, that one could only do it in some quite separated time of happy leisure—which came not.

This passage represents Ruskin at his most appealing and most human, combining self-deflation with a sort of Whitmanian wonder. I love the suggestion that moss does not quite exist at our speed, or the pace at which we live. It gives the lie to illusions of a single present, a spatial and temporal plane on which all creatures exist.

Ruskin continues with some lovely descriptions, and dubious theories, to arrive at the roots of moss. According to Ruskin, dead leaves of moss form the mulch for new growth:

They rise to form that crest, all green and bright, and take the light and air from those out of which they grew;—and those, their ancestors, darken and die slowly, and at last become a mass of mouldering ground. In fact, as I perceive farther, their final duty is so to die. The main work of other leaves is in their life,—but these have to form the earth out of which all other leaves are to grow. Not to cover the rocks with golden velvet only, but to fill their crannies with the dark earth, through which nobler creatures shall one day seek their being.

The mosses thrive through inheritance, each generation ceding light to the next. In the “mass of mouldering ground” there is an acceptance of decay, and perhaps a democratic intermingling (despite mention of “nobler creatures”). As Whitman writes of the earth in general in “This Compost”:

Behold this compost! behold it well!

Perhaps every mite has once form’d part of a sick person—yet behold!

The grass of spring covers the prairies,

The bean bursts noiselessly through the mould in the garden,

The delicate spear of the onion pierces upward . . .

Of course, some stones fall from bluff to creek with no accretions, their surfaces smooth. As the saying goes, “A rolling stone gathers no moss.” Delightfully, the Scottish rendering is, “A rowing stane gathers nae fog.” I always understood the proverb to mean, on the move, we accumulate no burdens or entanglements. Muddy Waters must have thought so, and the Rolling Stones after him. On your own, without a home, a complete unknown. But the proverb may have its origins with moss-gatherers, for whom a stone without moss would be a disappointment. I like the fact that the proverb plays both ways. Like many people, I lived with a fair degree of freedom when young, and I still think of freedom as both the ground of art making and the feeling it inspires. Yet I have willingly entered conditions of unfreedom in my life. I am bound to a few dear people and places. And in poetry, I undertake all sorts of constraints that channel my thinking, rhyme and meter among them. Poetry offers a dialectic between freedom and order, with the application of those very terms in contention.

For mosses and lichens, the rhymes would naturally be fuzzy: precisely inexact, blurred at the edges by their consonants, subtle to the listener’s ear. The rhymes interlock, rather than forming portable and extricable couplets. The rhymes embody a landscape; the sounds of the poem sound a place.

Mosses and Lichens

Grant but as many sorts of mind as moss

spread in profuse and tender shade

across the face of a granite block

that came to rest in the last ice age;

a buoyant clump of cushion moss,

the nap of sheet moss, fit for sleep,

a bog of sphagnum, shirred and soft,

along the bed of Pickle Creek.

Carpet mosses, loose yet dense,

absorb a day of steady rain,

pervasive, yet so reticent

that many have no common names.

More subtle still, an areole

of lichen lives on rock and air,

the crust of paint on a coping stone,

an orange blaze that marks no trail;

a flake of ancient bronze, an ash

that powders the fingertips like sage;

the reindeer lichen’s tangled mass

of antler branches, brow and bay.

Across the valley floor, the like

adapt to every circumstance

as through a mesh of dappled light

a lichen clings to every surface.

A row of oaks may call to mind

an ancient marble colonnade

at Samothrace, a mountainside

where shadows cleanly separate

in flutes around a fallen drum

and gods in golden ratios

still subdivide the setting sun

through one remaining portico.

But here the lines of sight get lost

in undergrowth, a sandstone shelf

fogged with lichen, furred with moss

so thick along the water’s edge

a falling walnut makes no thud.

Approaching fifty, Ruskin turned

his mind to moss, and taking up

a shaggy brick from the yard, observed

the leaves that die invisibly

and turn to humus, dark and wet,

remains that steadily accrete

beneath the bright ascending crest.

“Mosses and Lichens” from Mosses and Lichens (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019)

Born in 1970, Devin Johnston spent his childhood in North Carolina. He is the author of five previous books of poetry and two books of prose, including Creaturely and Other Essays. He works for Flood Editions, an independent publishing house, and teaches at Saint Louis University in Missouri.