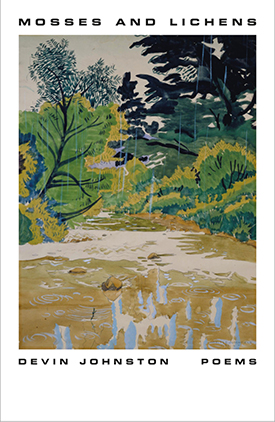

If a rolling stone gathers no moss, the poems in Devin Johnston’s Mosses and Lichens attend to what accretes over time, as well as to what erodes. They often take place in the middle of life’s journey, at the edge of the woods, at the boundary between human community and wild spaces. Following Ovid, they are poems of subtle transformation and transfer. They draw on early blues and rivers, on ironies and uncertainties, guided by enigmatic signals: “an orange blaze that marks no trail.” From image to image, they render fleeting experiences with etched precision. As Ange Mlinko has observed of Johnston’s work, “Each poem holds in balance a lapidary concision and utter lushness of vowel-work,” forming a distinctive music.

Johnston joined author and editor Robyn Creswell at McNally Jackson bookstore to discuss the unique uses of language and unexpected word choices in Mosses and Lichens.

Robyn Creswell: In reading and rereading Devin’s poems over the past week, I’ve been underlining the new words I’ve learned. We were just talking about some of them: “shirred” and “sphagnum” and “pipistrelle.” Some of them I looked up, some I didn’t. Many of them have to do with the natural world, which reminded me of an essay by John McPhee where he talks about how he was seduced into studying geology. He writes:

“Geologists communicated in English; and they could name things in a manner that sent shivers through the bones. They had roof pendants in their discordant batholiths, mosaic conglomerates in desert pavement. There was ultrabasic, deep-ocean, mottled green-and-black rock–or serpentine. There was the slip face of the barchan dune . . . There were festooned crossbeds and limestone sinks, pillow lavas and petrified trees, incised meanders and defeated streams. There were dike swarms and slickensides, explosion pits, volcanic bombs. Pulsating glaciers. Hogbacks. Radiolarian ooze. There was almost enough resonance in some terms to stir the adolescent groin. The swelling up of mountains was described as an orogeny.” [Basin and Range, Chapter 1]

I love this idea that you could be seduced into studying science or the natural world by way of its vocabulary, and I wondered if that was true of you as a poet.

Devin Johnston: I tend to be of two minds about the densities of diction. I like a plain style and I like, in a way, to be faithful to my own idiom. I feel that everyone is given, and accumulates, an idiom that’s theirs. It derives from temperament, family, friends, regions, work. It’s their at-home way of speaking and I value that. But then, I do get seduced by new words, in that I’ll experience something and think, there must be the right word for that, and go hunting for it. Sometimes there is and sometimes there’s not—and when there is, I can’t turn away from it once I’ve found it. And if the word is unfamiliar, its texture comes to the surface. We don’t take sound and spelling for granted as much. When that’s the case, I don’t mind a little obscurity: I feel poetry should be inconvenient!

Creswell: In that wonderful ending to “Neighbors,” in place of an epiphany or revelation, you give us a phrase in Somalian which, unless you speak the language, will be uninterpretable. Nor does the poem provide an interpretation—so it’s a kind of anti-epiphany.

Johnston: Unless you do speak the language. I like that it has that double possibility.

Creswell: But it’s also as if the solution is in plain sight. Like, “Here it is, here are the words, you just can’t understand them.”

In many of my poems, ironies are also mysteries.

Johnston: I think that’s right. In many of my poems, ironies are also mysteries. In relation to rare words, more generally, I also think of Hugh MacDiarmid. He was one of the poets—really, the main poet—to bring back Scots as a literary language in the twentieth century. To do that he had to invent new words—and take up very ancient words and bring them back into circulation. For him, a poem is a triumph if it restores a single word. He thought of his poetry as a project of recovery. I like that idea that you’re maybe bringing to the surface a word or two. It’s not as though they are going to enter general circulation because of my poem, but there—at least there—the lost words are brought back.

Creswell: You also have some wonderful list poems. I’m thinking of “Tangled Yarn,” for instance, from Traveler, which is a litany, I think—if I’m reading it correctly—of types of yarn. Is that right?

Johnston: It’s actually names for dragonflies and damselflies, folk and common names that are based on resemblances to knitting needles, among other things.

Tangled Yarn

Darner, sewing needle,

exclamation damsel,

pennant, flying adder,

tang- or sanging eater,

fleeing eather, bluet,

steelyard, spindle, booklet,

skimmer, scarce or common,

sand or shadow dragon,

cruiser, shadow damsel,

devil’s horse or saddle,

darning needle, dancer,

meadow hawk or glider,

water naiad, threadtail,

sylph or sprite or penny nail.

I don’t know what I’m trusting there. I’m certainly not trusting the reader to recognize the subject. And I don’t think it opens the poem up that much to know that I’m referring to dragonflies. The poem is bound together by its structure, by the rhymes, by the delightful associations of the names, even if you don’t know their reference. In addition to knitting needles and yarn, many of the names sound as though they might come from ballads or fairytales—and of course, a “yarn” can be a story.

Creswell: How do you find these words?

Johnston: Sometimes from my friends and neighbors, sometimes from books. Part of the time growing up, I lived in the western corner of Virginia and I would hear a lot of weather words that I don’t hear elsewhere. When I was writing “Above Ivanhoe,” from Far-Fetched, I dredged up as many such words as I could, asked an old friend for others, and probably dreamed a few: “A colt’s tail drags a scuff, / a handbreadth of cloud / skiffing across the gap, / its wake a drow of cold breath . . .” So, sometimes I’m able to do a little research, and sometimes it’s just a cache of language I happen upon.

Creswell: You have an essay in a book called Creaturely that begins by taking a walk with your dog and noticing how the world must present itself to the dog, with its keen sense of smell. You note the paucity of words we have as humans for smells, relative to the vocabulary we have for sight. But sometimes, when reading your poems, it seems that the world presents itself to you as sound—as if that’s your primary sense. There are all these moments in your work where language is uninterpretable, or simply left un-interpreted, or is otherwise nonsense; a lot of bird sounds and natural sounds. Is that the way you think of yourself as a poet?

Language is sound, so poetry is sound. The pleasures are aural and oral, heard and spoken.

Johnston: It took me a while to recognize that I do focus more on sound than other senses. I think that’s partly because language is sound, so poetry is sound. The pleasures are aural and oral, heard and spoken. I try to bring noise and music into my poems. Of course, we hear language as a particular subset of sound, and each syllable sounds more like another syllable than it sounds like anything else in the world. “Chip chip chip sweet-sweet-sweet sweeter-than-sweet” can only get so close to a yellow warbler’s song. But we can, at least, attempt an imitation, whereas the other senses are synesthetic in poetry, with sight, touch, taste, and smell rendered through sympathetic sounds.

I like the challenge of trying to get sensory experience into language. When I teach creative writing, I sometimes bring an herb from my garden and try to get the students to describe it with words. They quickly realize that they will have to draw comparisons: does it smell like this or like that? They have to get inventive and move into metaphor pretty quickly. I did that in a class randomly, just to try, and it seemed to go well. The next week I was teaching a little creative-writing group in prison and I thought I would do the same exercise. Normally, you have to get strict permission to bring anything into the prison. I have to itemize everything I bring inside, down to the pencils. And I was embarrassed to say that I wanted to bring fresh basil into my workshop. But, I thought, well, it’s just a plant, I don’t think anyone is going to care. So, I brought it in and passed around leaves, and the discussion was interesting, partially because the people I was working with hadn’t smelled fresh herbs in a long time. It was also possible that some had never smelled fresh herbs at all. I have such positive associations with basil, but to most of the participants it did not smell good. Their comparisons were largely negative, like burnt tires, along with notes of pine and pepper. Just as we were getting somewhere, the officers abruptly ended our class, sent everyone back to their housing units, and took me to see the deputy warden. Apparently basil is considered contraband. I kept saying, “How can basil be contraband?” The deputy warden said, “Men cut it into marijuana.” To make it weaker? Why is that a problem? They didn’t follow my logic.

That’s a long swerve from your question.

Creswell: No, not at all, and in fact it leads me to my next question. As we were talking earlier, you told me that among the prison population where you work, Roget’s Thesaurus is more popular than The Autobiography of Malcolm X is. I wonder why that is. Why is a book of analogies and similitudes, a book of words that lead to other words—like “Tangled Yarn”—so popular? What’s the power of that?

Johnston: I think there is an association with building vocabulary as a source of eloquence. The sense that your eloquence is your power. There are elements of truth to it. But I think it can be a naive position—that if I just open up the possibilities of synonyms, I can access authority and become persuasive. I hadn’t ever spent much time with thesauruses previously, but after that I did: what strange chains of flickering association! I also realized Peter Mark Roget was a fascinating character. Apparently, he was a compulsive person, and he created endless word lists as a coping mechanism, as opposed to a practical tool.

Creswell: One of the things that I love about the book is its structure, which sort of sneaks up on you, since it’s a matter of subtly interlocking parts rather than a grand framework. Sometimes I wonder whether I’m imagining these connections: the first poem talks about “days of slow connection” and that phrase stuck with me. For example, “Slow Spring” ends on the word “profusion,” and “profuse” is in the second line of the next poem. There are episodes that match in otherwise very disparate poems. There are three Ovid retellings. It seems like the book has no mechanical order, but it does has a network of relations. How did you think about making this book?

Johnston: Well, I don’t really write books. I just write poems one at a time and then put them together. But there are intuitive connections between poems that I trust will emerge, having to do with the constraints of my interests and life. Questions persist from poem to poem, and phrases continue to echo in my head. Sometimes I find those connections and draw them out through arrangement and revision, but I prefer that they be subtle. I want there to be some threads that run through a book; but I’m just as committed to the miscellany, which is a form of poetry book that makes its own demands. The advantage of a miscellany is that each integer, each poem, can remain itself more fully. When a reader takes up a book that’s presented as one theme, one narrative, or one idea that runs through it, the distinct qualities of a single poem tend to drop out. In any case, it takes me a while to find the right balance between coherence and variety. In this book, the three versions of Ovid were in some respects binding agents: they connected loose ends concerning nature, loss, violence, and being a parent.

Creswell: There’s also the motif of mosses and lichens, as in the title poem:

Approaching fifty, Ruskin turned

his mind to moss, and taking up

a shaggy brick from the yard, observed

the leaves that die invisibly

and turn to humus, dark and wet,

remains that steadily accrete

beneath the bright ascending crest.

It’s a lovely image: Ruskin looking at the brick and intuiting the accretion of the dead behind the visible surface. You have another poem with that lovely line, “To think of what survives!” It seems to me a collection of poems about ruins and aging, but bright on the surface.

Johnston: Ruins and survival must be perennial themes of middle age, and they certainly run through Mosses and Lichens. These are also central sources of anxiety in an age of climate change. I don’t tend to address such a large crisis directly, but it’s just beneath the surface of some poems. My response is often to shift the scale of time and attention. I’m not sure if that’s necessarily reassuring, but at least it shifts perspective. And it creates a dynamic quality within a poem. In “Mosses and Lichens,” I’m looking over Ruskin’s shoulder, at the generations of tiny moss leaves. In the poem “Prehistoric,” I move from the present moment, on a hike with my kids, to the scale of geological time. Such overlapping temporalities have always fascinated me. We experience them everywhere, but I do in particular ways in St. Louis. There are many layers of history visible. I can walk down Louisiana Avenue and feel that I am in the nineteenth century. Our sewage system was built in the 1880s and hasn’t changed. Our alley is still paved with bricks. Sometimes there is a kind of heterogeneity of time that I am trying to get at in the poems.

Overlapping temporalities have always fascinated me.

Creswell: Speaking of St. Louis, it’s a city with several great poets: T.S. Eliot and Frederick Seidel, just to mention two published by FSG. Do you think of St. Louis as a poetical place? Is that in the background of what you write?

Johnston: It is very much in the background. I think I’m more interested in the way that it is not written, rather than in the way that it has been written. The book of essays I wrote, Creaturely, came in part from that instigation. I felt as though St. Louis is a city where large swaths are totally unrecorded in literature. Of course, there have been writers there and writers from there for a long time. But much of the city’s life doesn’t enter books. That seems to offer an interesting challenge.

Creswell: You have a number of poems about your children—often to do with the interesting language they use. What do your kids think about those poems?

Johnston: Those are the only ones of mine they read! Naturally, they look for their own names in a book—and then sometimes have complaints at the quotations and portrayals. But I hold on to an outdated idea of privacy. I have it for them, but for myself, too. I name them in poems, occasionally, but I feel awkward doing so.

Creswell: But they’re not intimate portraits, really. They feature more as ways of using language, as clusters of words.

Johnston: Or as features of childhood more generally. I always write from material close at hand, including the people most dear to me, and I rarely invent anything whole cloth. But I finally think of poems as fictions. I’m not interested in fidelity to biographical fact, but to truths of emotional and perceptual experience.

Born in 1970, Devin Johnston spent his childhood in North Carolina. He is the author of five previous books of poetry and two books of prose, including Creaturely and Other Essays. He works for Flood Editions, an independent publishing house, and teaches at Saint Louis University in Missouri.

Robyn Creswell teaches Comparative Literature at Yale and is the author of City of Beginnings: Poetic Modernism in Beirut. A former poetry editor of The Paris Review, his writings have been published in The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, and The Nation.