“This is a powerful, timely, and troubling book. Boyer’s unflinching account of the market-driven brutality of American cancer care sits beside some of the most perceptive and beautiful writing about illness and pain that I have ever read.”

—Hari Kunzru, author of White Tears

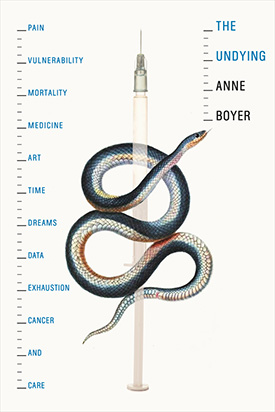

A week after her forty-first birthday, the acclaimed poet Anne Boyer was diagnosed with highly aggressive triple-negative breast cancer. For a single mother living paycheck to paycheck who had always been the caregiver rather than the one needing care, the catastrophic illness was both a crisis and an initiation into new ideas about mortality and the gendered politics of illness. A twenty-first-century Illness as Metaphor, as well as a harrowing memoir of survival, The Undying explores the experience of illness as mediated by digital screens, weaving in ancient Roman dream diarists, cancer hoaxers and fetishists, cancer vloggers, corporate lies, John Donne, pro-pain “dolorists,” the ecological costs of chemotherapy, and the many little murders of capitalism. Boyer joined Hari Kunzru, author of White Tears, in conversation at New York University.

Hari Kunzru: I’m really sorry you had to write The Undying but I’m happy that we have this book. At one point in the book, you mention that there’s this noisy part, the part that’s channeled towards an understanding, a set of causes that are acceptable. And then there’s the quiet part. Can you say a bit more about that distinction?

Anne Boyer: There is a mode of evidence and provability that has to do with cancer— along various legal machinations that make it really hard to go to court and to say that someone or something gave you cancer. There are also exceptional legislative protections surrounding the industries that create carcinogens. The terrain, therefore, on which we are given to understand how something like cancer is happening to us is an intentionally muddy terrain in which anything like “the truth” has thousands of barriers erected between ourselves and it. I know that there are cancer researchers who want to know why cancers happen and have their suspicions why, but they get funding for only certain kinds of research. For example, gene testing is incredibly profitable, but challenging the corporate right to poison our common world is not only not profitable, it’s dangerous. It threatens the financial and institutional sources that keep science going. I know there are research oncologists who are as frustrated about this as I am. For the patient, it might be even worse.

One of the rejected subtitles of my book was “An Epistemological Thriller,” because how can you know the truth when your very capacity to know the truth is under attack and yet your life depends upon it? Every instance of chemotherapy created an increasing amount of cognitive damage. As I was writing this book, I was losing my mind as I knew it and my capacity to think in the way I once had. Along with this accruing cognitive damage, I was also, reasonably, feeling a lot of stress, too, which also affects a person’s ability to think clearly. I was in a world in which knowing what the truth was a matter of life and death because I had to make certain kinds of decisions about keeping myself alive, and I desperately wanted to stay alive. I was not ready to die. I had so much to write.

I desperately wanted to stay alive. I was not ready to die. I had so much to write.

At the same time that this is all happening, a person with cancer is experiencing this ideological onslaught of correctives about what they are even allowed to feel, think. Everyone who would indicate a kind of environmental etiology for their illness would be immediately condemned as paranoid because the world that might provide us with answers is a paranoid structure, intentionally, with an opacity and impenetrability about it. What helped me was being a poet, because poets are experts in mysteries, and negativity is our terrain. I knew that what I was looking for did not have to be a scientific argument. I didn’t have to make a legal argument. I had different kinds of capacities to gather things together, a different terrain of truth, and a different terrain of proof. So that’s the truth I set out to find.

I will never know why I got cancer. I will never know why I lived and somebody else in similar circumstances died, and I have an example of someone in the book who had the same cancer and treatment that I did, who does die. I will never know the answers to any of this, but I know this other kind of truth which is half of us will have cancer or some sort of malignancy in our lives. We all have cancer. This world has it. It permeates the shared, industrial capitalist environment. Its devastation is unequally distributed so that the poorer you are, the more stress you have, the more prejudices you face, the more likely that you will face the more devastating consequences of the disease. I call this the “white-supremacist-capitalist-patriarchy’s carcinogenosphere.” People say “fuck cancer” but what they should be saying is “fuck all that.” That’s all what it is—this whole sort of interlocking set of economic and social systems of environmental destruction.

Kunzru: The very mouthful of that shows how very difficult it is to try and tell that. The way that most people resort to telling that is to use the first person and then to fall into this pitfall of a highly personalized cancer narrative. You say you have the advantage of being a poet but there is a great kind of narrative pressure on someone who is trying to write about their cancer. There is a pressure to give it a kind of arc. Could you say something about how you short-circuited these narratives of “the survivor” and “the heroic cancer warrior”?

Boyer: The first thing I did during diagnosis was to start reading. I looked at what had been done before me, and I could see a relationship of the great works about cancer, like Susan Sontag and Audre Lorde, to their specific moments in history. I thought: what if I do something like that for now and this particular moment? I can’t do it exactly like them because each one had different motives, different needs, and different history, but I could try something for our time. There was this moment in the history of breast cancer narratives in which a woman never said “I,” like with Sontag. Then there’s Audre Lorde’s work, in which saying “I” and personalizing the experience was utterly powerful—an “I” that became a chorus of “we’s.” Yet, neither of those was right for the present because we live in a time where these personalized narratives are highly marketed, used for ends other than our own.

I am being targeted for all of these breast cancer ads these past few weeks because the internet is mistaking me as an active breast cancer patient because of this new book, because of the stuff that is coming in and out of my email right now. One of the ads that keeps coming up is a fictionalized portrayal young female bloggers who adjust the camera, look into it, and say that “not all things happen for a reason.” The actresses tell sad, personal stories of cancer, and you’d think, given the degree of pathos, that it’s an ad for a breast cancer charity, but it’s actually an ad for a drug. The pharmaceutical companies themselves have mobilized the intimacy and intensity of this highly personal mode of communication, the individual narrative of the suffering woman. Seeing these, I had fires of rage, hell fires. Also, about the fifth time I saw one of these, I began thinking, “Good thing they can’t take The Undying and use it like that!” Imagine the drug company, the marketers, trying to create a complex literary work to say how great the drugs are. The very form itself has to refuse. To write at this moment, a person has to do something that formally or structurally baffles the way that the marketplace is going to absorb it.

This is not a rejection of the personal, but a commitment to be careful about the way I use it—there was a time that I thought there wasn’t going to be very much personal stuff in the book. Then I recognized that that was bullshit because if I don’t just go ahead and say that it was me, then that was another sort of deception. So, I asked myself: how do I show the material particularities of my life, and how I’m me in all my fullness and a little point in all of these other structures, meanwhile never forgetting those different than I am and those in the past? And I thought, if I can write a very historically particular book, to try to capture this very moment, I will make something that neither gives a lie that it wasn’t my body, I will not make the lie of an intellectualizing abstraction, but at the same time hopefully—not always successfully because there are parts of it that are self-indulgent, too—avoids the enforced, sentimental testimony of the suffering woman, the performance and pleasure of suffering that the marketplace still feed on.

Kunzru: There is a very weird intimacy in female autobiographies between the sick body and female subjectivity. I noticed Marjorie Kemp turning up in your book. In many of these narratives, the suffering is the subjectivity. You’re acknowledging that in the strangeness of that tradition in this book but also evidently trying to get out from under it. Can you say more about that?

Boyer: The valorization of pain is just not good enough for me. I’m not going to do that because I actually want something else.

Kunzru: It seems like prosperity gospel, all the ideas that have been formalized by our president; “visualize it and that will be the outcome that you have.” That sentiment seems to linger in some parts of the culture. And it’s especially intense around cancer. Always individualized, always about self-management.

Boyer: Right, that this ideological pressure intensifies around cancer is a pretty good sign a cancer is the ground in which we are fucked over. The discipline around it is so intensely individualized. I’m going to read the negative here: they’re drilling us so hard on cancer because cancer is a window into the structure of the world that is so often made opaque. Cancer is the direct result of the way that industrial capitalism has taken our shared world and turned it into a world of profit in which our lives are diminished through this.

Cancer is the direct result of the way that industrial capitalism has taken our shared world and turned it into a world of profit in which our lives are diminished

Kunzru: I think until I came to the U.S. I didn’t quite understand the extent to which healthcare is used as a form of social control, and that’s very present in your book. This moment where you have to teach three hours of Whitman in a state of near collapse and intense pain. You’re not even able to carry your books into this classroom. That’s a situation which I think sums up a great deal about why it’s important not to shut down these systematic, structural explanations.

Boyer: Because we die. We die without healthcare. And how do we get our healthcare? It depends on which state you’re in now with Obamacare—but places like Kansas do not have a Medicaid buy-in, so it’s been in many ways a worse situation for working-class people post-Obamacare. Your job that provide health insurance is your life, or maybe it’s that relationship you might want to leave, but you stay in because you’re like: but I would die without healthcare. And so it is used as this form of social control. Once you’re subjected to the struggle to get health care, there’s all the other specific stuff that goes on around it. But at the same time this is happening: the individuals, many of the individuals I’ve encountered, many of the workers who gave me care one way or another, kept me alive inside of this system in which your life is exploited for profit and in which you are often in peril. And then you have these little miracles—the hugs, the guy in the ambulance who I got to have an amazing discussion with, in which he says “Medicine’s an art,” he’s like, “We call it a practice. We don’t know what we’re doing so we just keep practicing.” So we had this talk about which was more noble, literature and philosophy or the practice of medicine. And we had that conversation because I passed out in IKEA and he had to retrieve me from the knife section and pulled me out on a stretcher in my Cleopatra wig! There are these miracles, these individual miracles that happen inside of these systems that always lead me to believe, well to imagine, that if people are this awesome now—in a system that sets us all against each other at the price of life or death—imagine how much we could multiply the potential for human existence and for the existence of the planet if we lived in a world in which we didn’t feel as if the next move was going to have us lose our housing, lose our jobs, lose our healthcare, lose our lives.

Anne Boyer is a poet and essayist. She was the inaugural winner of the 2018 Cy Twombly Award for Poetry from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts and winner of the 2018 Whiting Award in nonfiction/poetry. Her books include A Handbook of Disappointed Fate as well as several books of poetry, including the 2016 CLMP Firecracker Award–winning Garments Against Women. She was born and raised in Kansas, and was educated in its public schools and libraries. Since 2011, Boyer has been a professor at the Kansas City Art Institute. She lives in Kansas City, Missouri.

Hari Kunzru was born in London, and is the author of the novels The Impressionist, Transmission, My Revolutions, and Gods Without Men, as well as a short story collection, Noise and a novella, Memory Palace. His novel White Tears was published in spring 2017. He was a 2008 Cullman Fellow at the New York Public Library, a 2014 Guggenheim Fellow and a 2016 Fellow of the American Academy in Berlin. He lives in New York City.