In his later years, when he had lost nearly everything, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa would descend alone every morning into the roar of Palermo, clutching a small black bag containing a volume of Dickens, a notebook, and a blue biro pen. He would walk slowly, like a man trying to remember his way.

The streetside doors of Palazzo Butera, Lampedusa’s final home.

He was writing, of course. Turning sentences over in his mind, measuring them. The cafes and the antiquarian bookstore he would walk to and spend his days working in—the Mazzara, the Massimo, Flaccovio’s—are vanished now. But the rhythms of Palermo’s old quarter as it once was, the heat and buzz of Vespas and diesel trucks and donkey-carts banging up off the ancient stone buildings, and the sudden hushed gloom of the old cafes, their half-empty tables and clinking of espresso cups, can still be felt in Lampedusa’s sentences.

I went to Sicily to find that world, to seek out Lampedusa as he had been, to retrace his steps and see what, if anything, remained. My own novel was in its final draft. Lampedusa, already dying, was my character; I wanted him introspective, filled with memory and regret, puzzled by a life he felt he had not lived fully. It would be a novel of regeneration. I had located my story in the last years of his life, during the difficult writing of The Leopard, amid a world of decadence and decay, a world still reinventing itself after the destruction of the Second World War. Since everything would be conveyed through Lampedusa’s eyes, I saw early that the Sicily of my novel would not be a Sicily anyone could visit. It would be Palermo as Lampedusa alone had felt it; it would be Capo d’Orlando and Palma di Montechiaro in a time now vanished, through a consciousness no longer recoverable.

Lampedusa’s ruined childhood home has been rebuilt, converted into luxury apartments

Palermo is a city of initiations: you must be invited in. It is very old, but every turning hints at something unseen. The long winding streets will open suddenly onto cobbled squares ringed by restaurants. Stone fountains, public gardens, the sudden expanse of a wide sunlit road crowded with cars: you round a corner, and the shaded curving stillness of a Moorish alley shuts out the modern city behind you like a curtain closing. It seems the cityscape of a dream.

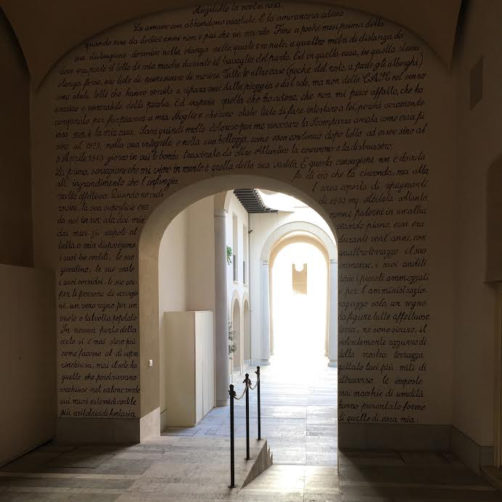

That dream, for Lampedusa, centered itself on the ruined shell of his beloved childhood home, the Palazzo Lampedusa. It has been entirely rebuilt in recent years, converted into luxury apartments; if you stand in the street and peer through the metal gates, you can see, in the courtyard, a wall mural reproducing a handwritten page of The Leopard. It is all very white, clean, calm. But in Lampedusa’s final years, when he was writing his novel, that property was boarded up and locked, a ruin of broken stones and brickmaking equipment and weeds and waterlogged papers. Lampedusa hated to go there: its loss ached terribly. His mother had died in its ruins; its destruction came to represent, for him, the annihilation of a once-great family. I was amazed, then, to see how close the ruined palazzo stood to the cafes he had elected to write in, each day—only a few minutes away.

Lampedusa was born in 1896, five years before his cousin, Lucio Piccolo, who would become his confidant and writing peer. Lucio was brash, self-aggrandizing, brilliant. He lived his whole life in seclusion with his older brother Casimiro and his sister Agata Giovanna in a villa far along the coast, at Capo d’Orlando, overlooking a windswept sea. Their mothers were sisters, last of the five dazzling Cuto daughters—charismatic, beautiful, scandalous.

The Piccolo’s villa, at Capo d’Orlando

It is a morning’s drive along the coast from Palermo to the Piccolo villa. There I felt, for the first time, the presence of Lampedusa. The villa’s gardens and all its rooms have been preserved, like specimens under glass. I saw the empty plate and glass set out at the head of the dining table, left there by the Piccolo siblings for their deceased mother. They believed her ghost haunted the villa, my guide explained; they believed she joined them for dinner each night. And I saw too through the window of the guest room—a room reserved for Lampedusa, its sole occupant in that last decade—the faint grey haze of an island in the distance. “That is Salina,” I was told. It was here, from this view, that Lampedusa first dreamed up his character, Don Fabrizio, Prince of Salina. Outside I walked the long trellis in the gardens, and stood at the gate to the pet cemetery, where the Piccolos buried their beloved dogs. The air was deep, lush, the earth soft and muddy underfoot, the gardens overgrown with long grasses.

Lampedusa was least lonely in the company of his cousins. He and Lucio and Casimiro grew up teasing and cajoling and talking and dreaming together, in the gardens at Capo d’Orlando. They were all reclusive, and peculiar, all deeply immersed in the European arts. Casimiro was a painter, Agata Giovanna a botanist. Lucio spoke a half-dozen languages, was a librettist, a musician, a poet. When Lucio received a poetry award from Eugenio Montale, in 1954, Mondadori agreed to publish a collection of his verses. “Knowing I was no greater a fool than he,” Lampedusa later joked, “I decided to sit down and write a book also.”

The guest room reserved for Lampedusa, at the Piccolo’s villa

But it did not come easily. He had dreamed of his novel for decades but never started the writing of it. By the summer of 1955 he had completed the long first chapter of The Leopard, but could write no further; he was looking for something, some way in, to locate what would come next.

He found his answer on the far side of the island, in the town of Palma di Montechiaro. He had never been there, in all his life, though he had been the patron of that town since his father’s death. The island of Lampedusa—the heart of the current refugee crisis—lies just off its coast. Palma di Montechiaro is a quiet town situated high on a steep slope, set back from the sea, it is filled with light, dizzying with stairs and winding uneven roads. The church stands high at the top of a long wide public steps. I went there uncertain of what I would find, of how much would remain from Lampedusa’s day; surprising, then, to learn how little had changed. Inside I saw pink marbled columns, which Lampedusa himself had traced his fingers over, amused, for the marbling was merely painted on. I saw the ancient wooden bench within the enclosure, reserved for the prince’s family. The great painting over the altar with Lampedusa’s own ancestor, Giulio Tomasi, painted into the biblical scene.

A lily pond in one of the gardens at the Piccolo’s villa

Five miles from the town itself, on a craggy cliff above the sea, stands the ruined castle of the Tomasi. It is usually closed to visitors, but the generous presence of a local historian meant that we made the hike up the scree and along the cliff to the gates, which were then unlocked with a remarkable old Sicilian key, like a small iron mallet twisted by fire. Inside all was quiet, filled with light and rubbled walls. The small chapel had been restored, filled with its own emptiness and the presence of its Christ. On the day we walked the ruins, the sun was high and hot, the shadows were stark in relief on the weeds growing between the stones. I stood at a ruined window staring out at the blue Mediterranean. I climbed a staircase next to the ruined tower and leaned into the battlements and watched the light on the cliffs. There is a famous photograph of Lampedusa, in his shirtsleeves, smiling in happiness with his adopted son Gioacchino, both of them standing in the flat sunlight among these very ruins. I stood in that same light and squinted, feeling for a moment something of that same strange joy.

• • •

I met Gioacchino Lanza Tomasi and his wife Nicoletta on a bright Saturday afternoon in Palermo. They had kindly agreed to take me on a tour of Palazzo Butera, inherited from Lampedusa’s late wife, Alessandra. Gioacchino is Lampedusa’s heir and adopted son—and a character in my novel.

Behind the Piccolo’s villa, Agata Gioavanna’s orchards are still in use

I had slept badly; I was nervous about meeting him, anxious that he might resent the novel, or his presence in it, or not resemble at all the youth I had imagined into my story.

I need not have worried. At eighty-five, Gioacchino is still all courtesy and elegant amusement. I saw at once the Tancredi in him, the mischievous eyes, the quick dry smile, the casual grace and unhurried gesture. He received me on the balcony of an interior courtyard, a small potted basil on a rickety table in the sunlight at his elbow. Despite the heat he was dressed exquisitely in a three-piece suit, the living memory of the man I had come to study. We went through into the oldest room in the palazzo, its thick carved beams constructed for the Arab fortress that the palazzo had been built around. He began to speak of the ruin, of Lampedusa’s poverty, the sadness that had haunted his final years.

“The man was penniless,” he explained. “Everything was walls. This was walls, that was walls. They had no plumbing, nothing.” He paused. “He was a man completely in despair. You must imagine a man that was, so to say, so unhappy of his life. He had no money, nothing. He had the idea of the memories of things.”

View of the Mediterranean from the ruins of Lampedusa’s ancestral castle, outside Palma di Montechiaro

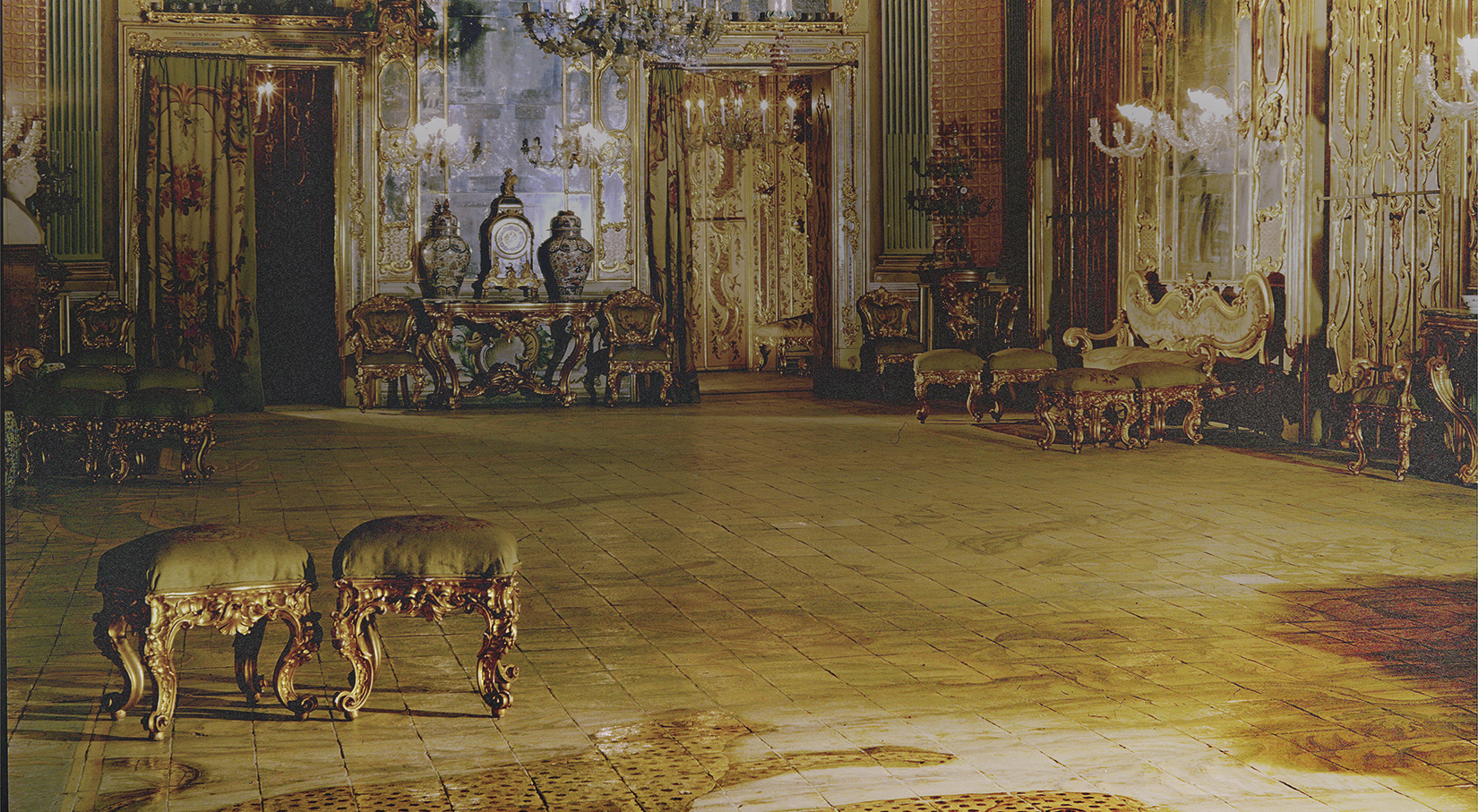

We walked on, deeper into the palazzo. Past the small room facing the sea where Lampedusa had slept, out onto the wide terrace, filled now with trees and a garden but, in Lampedusa’s day, stark and empty. Then back inside, up a flight of steps, through long rooms filled with ancient books, carpets, strange dark wooden cabinets. In Lampedusa’s final years the rain would soften the walls of the bathroom, turn them dark. The great ballroom, with its high windows facing the Foro Italico, was kept shut, for the ceiling had collapsed in the bombing during the war and Lampedusa could not afford to repair it. He filled it with damaged furniture and broken objects pulled from the rubble of his beloved childhood palazzo, on Via di Lampedusa. He used to say Via Butera was his house, Via di Lampedusa his home.

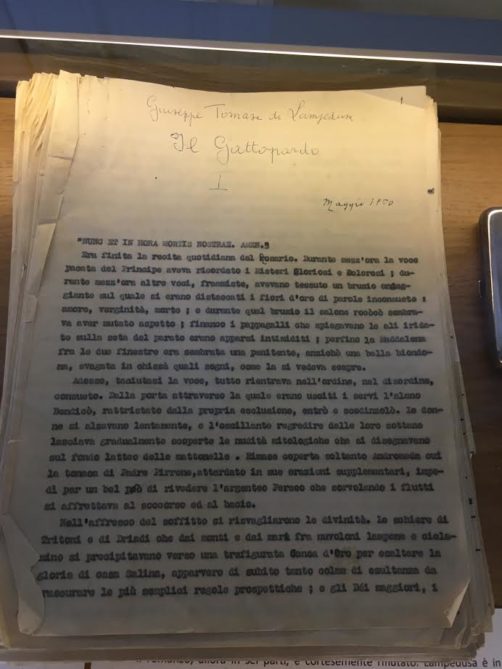

All of it has been restored now, first by Lampedusa’s widow, later and more completely by Gioacchino himself. Everything now is bright, exquisite, clean. In the grand ballroom, Gioacchino showed me a glass case holding the handwritten manuscript of The Leopard, and its typed fair copy, with corrections in Lampedusa’s own hand. Also his diary, his daybook, his letters.

The castle from below

“I cannot tell you much more,” Gioacchino continued. “About Sicily I can tell you more. About him? The last years, they were severed, in the sense that he was a broken man and his wife tried to encourage him, saying why don’t you do this and why don’t you do that, and why don’t you write your book and why don’t you give lessons, and this boy is nice why don’t you adopt? He would have done nothing. Instead he enjoyed it, and he would have gone on. That is the point. You think: he didn’t stop when he couldn’t have a publishing house during his life to print it. He started again.”

Did he feel he understood him differently now, I wondered, after all these years?

“I understand him more now,” Gioacchino replied. He was older, I knew, than Lampedusa had been when he died. He added quietly: “He was much more, I think, than the book.”

Gioacchino’s cell phone buzzed; he had forgotten an appointment with another guest. He left me for a time. I stood alone, waiting, listening to the silences of the palazzo. Footsteps approached on the floor above, passed, fell away. Through a door stood the historical library, preserved as it was in Lampedusa’s day. It was filled with the ghost of Lampedusa. He was there in the old volumes lining the shelves, arranged by country, the gossipy histories of court life, the diaries of German countesses, the grand multi-volume biographies of Napoleon in French.

Gioacchino Lanza Tomasi, in one of the libraries in the restored palazzo

The light coming in from the courtyard windows fell across a herringbone hardwood he had once admired; it was easy to imagine his ghost standing in its light, dignified, watchful, turning the slow pages of his manuscript, making corrections, crossing out. He would be pleased, perhaps, by his novel’s success, saddened perhaps by the world as it is. “In order for things to stay the same,” he famously allowed a character in his novel to say, “things will have to change.”

He had meant Sicily, of course, in the tumultuous age of Garibaldi; but he could have been describing the human heart.

Steven Price is the author of By Gaslight. His first collection of poems, Anatomy of Keys, won Canada’s 2007 Gerald Lampert Award for Best First Collection, was short-listed for the BC Poetry Prize, and was named a Globe and Mail Book of the Year. His first novel, Into That Darkness, was short-listed for the 2012 BC Fiction Prize. His second collection of poems, Omens in the Year of the Ox, won the 2013 ReLit Award. He lives in Victoria, British Columbia, with his family.

The typed first page of The Leopard, with corrections in Lampedusa’s hand