Brookdale, California

some days, but mostly night

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 8TH, 2016

When you are in a conflict, settle yourself: feet on the floor, eyes closed, deep breath. Imagine that you and the person with whom you disagree will meet in a room. You knock on the door and when you go in, you ask, respectfully, what do they need that you aren’t giving them? What don’t you know that you should know? The woman who performed my wedding ceremony taught me this. And it usually works. I find my own unwillingness. I find surprises and solutions.

As the votes come in, I close my eyes and imagine Donald Trump’s office. I take a deep breath and knock. The door creaks inward but no one answers. The light is off. His chair is spun to face the wall, its back toward me. “Hello, hello,” I say, as I walk around it to face him. But there is no one. On the seat, instead of a man, there is a joystick. It is old-school, Atari-style, black rubber and a yellow button. And I run from the room and the game, the gamers, the game boys, the boy games, the war games, the warmongers, the alt-right all-wrong controlling that lever that is Trump. It’s not that there are no questions. It is that there is no one to ask and I lie there with panic attacking instead, hyperventilating, teeth chattering. I finally sleep and dream of my sons a few years from now, eight or nine, ten years old. They wear all black and lean against a police barricade, their blonde hair already graying to ash.

DAYNIGHT

My husband and I wear safety pins in our own house where I’m the only woman, a white woman, and yet, the only obvious potential victim of oppression under the new regime. My husband is tall, white, male, hetero, handsome, white, did I mention, white? Our sons are like him, so far. We wear the pins because we feel unsafe anyway, even with each other, and their silver sharpness glints in the candlelight burning in every room. Electricity is too bright, too morning. We take aspirin for hangovers we don’t have. There is no mourning without u. We proclaim ourselves safe spaces; pin, but can’t connect, to each other or ourselves. We’re parents first, aren’t we? We talk about passports and flight. We’re fighters first, really, and we talk about burning it down, building it again. I count the number of four-year terms before our oldest son can be conscripted: three and a half. That’s how old he is now: three and a half. “Mommy?” he interrupts us, “Daddy? Why is it so dark?” My boys scream in their sleep and wake me from a dream of breaking into a pharmacy; I’m stealing morning-after pills, Mission Impossible-style, for the underground reproductive-freedom railroad. I’m too old to have more children, the pills are not for me. I steal because I had a choice. I steal choices for others.

Electricity is too bright, too morning. We take aspirin for hangovers we don’t have. There is no mourning without u.

NIGHT THE NEXT

I live on Black Twitter, mouth shut, so one more white girl can learn to be a better ally, and the first lesson is to shut my mouth. The second lesson is that my election-related shock is another symptom of my privilege. Fucking duh. It shouldn’t have taken twenty-four hours to figure that out, it shouldn’t have taken twenty-four seconds. Next, the safety pins. Just another poke to black Americans who aren’t facing a new kind of oppression this week, in Trump’s America, than they were last week, and where the fuck was my safety pin then? I put my safety pin back in the sewing kit and try to imagine real mending, how to act the part, not dress for it. I dream of walking forever in protest. Kid Rock walks in front of me and I tap his shoulder, ask him how his campaign is going though I want to tell him he got in the wrong line. He won’t speak to me but Myron What’s-His-Face, Trump’s head of EPA-transitioning and Planet Earth-capsizing, zips by us in toe shoes saying that he stopped drinking coffee and is feeling great. I wish I hadn’t worn these cowboy boots because there is a long way to go.

DARKTEENTH

I’m on the gender-diversity committee at my kids’ school and tonight is our first meeting. As I’m leaving the house my husband holds me too long and won’t look me in the eye. “Leonard Cohen died,” he says. When I walk into the meeting, I pull Cohen’s darkness in with me like a child dragging a toy. The parents gathered use words like “long-range plans” and emphasize the importance of “not disrupting the curriculum.” One woman makes it a point to share she would feel very uncomfortable being called “a they.” To my credit, I do not choke them, I mean, her, when she says this. The room looks at me like I’m crazy when I sputter at the idea of disruption as the enemy, when I offer an immediate step, “What if we ask the teachers to just not say ‘boy’ or ‘girl’ for a week? Can we try that?” We can’t try that. Not without more meetings, something written up. A memo. I explain that this is what I do in my classroom, that I ask students to express their preferred gender pronouns to me, I don’t decide for them. They ask me for the training material I was given by my college so they can look it over. Training material? A memo? My hands are fists in my sleeves. But we can change the words, I say, the words are hurting our children, I say, we have this power right now, I say. I am disruptive enough to make it so we’ll have a response from faculty about this idea at the next meeting. In a month. The drive home is as heavy as all of the poems Cohen wrote that he called songs.

But we can change the words, I say, the words are hurting our children, I say, we have this power right now, I say.

DARKEMBER

It occurs to me that I might have, just a little, taken some of my anger out on the parents at the gender-diversity committee meeting. It’s not their fault that Trump was elected and that my mother raised me on action. It’s not their fault Leonard Cohen died or that my father raised me on road trips singing his lyrics. It’s not their fault I’ve never found the I in team or the patience to wait for it. I can’t . . . team. I don’t know how. I’ve never played a team sport. I hang by a thread in a marriage others would cling to. I lurk in A.A. where drunks accept that I hate them and they hate me and we’re good. The only place, the only people, I have ever wanted, are us. Right here. You and me. The ones who know that words matter. All the words: wall and ban and pig and dog and bad face and rapist and boy and girl and he and she and him grabbing a pussy and her getting locked up. Those words are walking around now, lighting fires, shining red in people’s eyes, shaping our children. What are we going to do about them?

REMEMBER

And then I remember. The answer is in the question. The words. Words are ours. Our friends, our tools. Words are our team, party, and platform. They line up, work, demonstrate, for us. The words and I know what to do, just like they do with you. We must gather them, gather ourselves, here, right here between these pages, and those pages, and the next pages, in the margins and the center, in this room and outside, we must shine them into swords, burn them into torches, fly them into doves. This night is ours. Let’s light it up with words.

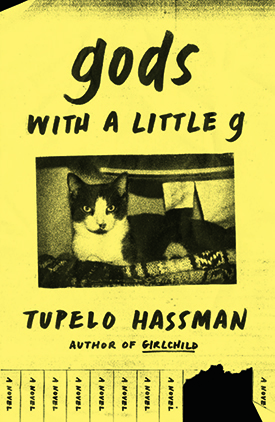

Tupelo Hassman’s debut novel, Girlchild, was the recipient of the American Library Association’s Alex Award. Her work has appeared in The Boston Globe, Harper’s Bazaar, Imaginary Oklahoma, The Independent, Portland Review, and ZYZZYVA, among other publications. She is the recipient of the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame Silver Pen Award and the Sherwood Anderson Foundation Fiction Award, and is the first American to have won London’s Literary Death Match. She earned her MFA at Columbia University.