I speak and write four languages: Medumba, which is my mother tongue, English, German, and French. I was educated in French and German, and started teaching at a university in Germany, something for which I was prepared at the University in Yaoundé. My first job was in Central Pennsylvania, where I was an assistant professor of German. My students all found it quite amusing, learning German from a Cameroonian, a Black man whose first language was French. I found it amusing too, and I remember provoking the laughter of the Caribbean writer Édouard Glissant, the master of créolité, when he visited my university and assumed that I was in the French department. I told him, no, and he had to pause. I quickly added that mine was simply the story of Cameroon, the story of a life in four languages.

For indeed Cameroon has been battling its three colonial pasts since 1919, when the Germans lost World War I. The French and the British, the winning colonial powers, thought they had settled the case of the bellicose Germans on foreign African soil by claiming its colonies for themselves. Little did they know that their three-way confrontation would have a second act during World War II. More importantly, Cameroonians themselves could not imagine that one is never freed from the linguistic colonial past.

I have several versions of my life’s entanglement with Cameroon’s history, but the most amusing remains the fact that my life has made my tongue the place where the history of my country’s battle with itself is continued. I might joke about it at home in the United States when speaking to my wife in German, then turn around and speak to our daughter in English, before finishing a text I am writing on my computer in French.

The other day, I realized that I have spent my whole adult life in countries whose public language I have not mastered completely. And I envy the English-speaking African writers in particular or any writer, who, because of his or her British descent or US descent for that matter, can easily navigate the British or American literary worlds. I write in French, and as a closeted Francophone writer living in the US, it quite pains me to explain why I hang on to a literary world centered on Paris, when New York is the place where I have most of my professional friends. I had the same sentiment when I was living in Germany—as a Francophone writer, I could not fully participate in the literary discussions going on around me. I spoke German and I wrote texts in German—for instance, my dissertation—but published my literary work in French. The joke was, and it remains a personal joke, that I only speak French with my computer. French remains the intimate language of my literature, in a world lived first in German and then in English.

It is impossible for me, as a Cameroonian, to move outside of one of the colonial languages in which I was born.

But my attachment to the French language, when I think of it, reflects the fact that it is impossible for me, as a Cameroonian, to move outside of one of the colonial languages in which I was born. In Cameroon, French and English are not simply languages, they are new ethnicities. Which is to say that they sink into one’s mouth only to possess one’s belly, and even one’s life. Cameroon has not managed to extract itself from the violent confrontation among these three colonial languages.

The news will tell you that since 2017, the country has been sinking into a war between the English-speaking population and the Francophone population which had ruled the country since the end of WWI—an ironic situation, as Cameroon may be the only country in the world where English is in fact a minority language.

The dual condition of being both a minority and a new ethnicity presents a dangerous predicament in the English-speaking regions of the country where the war is raging. Being Anglophone is no easy feat in Yaoundé, the city where I was born and raised. Yes, Cameroon is at war with itself—a mostly Francophone tyranny is using all the instruments of state violence to terrorize an Anglophone minority which it has always marginalized. It is a war nobody can fully understand without going back to the German loss of 1919. Cameroon is trapped in a civil war no African really wants to understand because Africans mostly insist on the fact that we have African languages. Yes, I have an African tongue. And yet I have four languages.

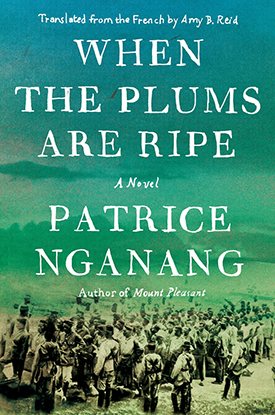

Patrice Nganang was born in Cameroon and is a novelist, poet, and essayist. His novel Temps de chien received the Prix Marguerite Yourcenar and the Grand prix littéraire d’Afrique noire. He is also the author of La Joie de vivre and L’Invention d’un beau regard. He teaches comparative literature at Stony Brook University.

Amy Baram Reid is a professor of French language and literature at New College of Florida. In 2016, she received a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Translation Fellowship for When the Plums Are Ripe.