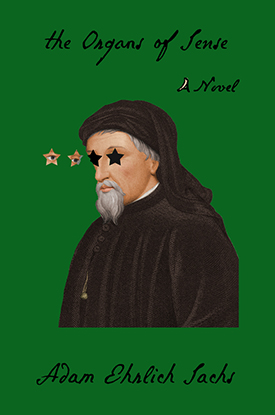

In Adam Ehrlich Sachs’s The Organs of Sense, the year is 1666 and an astronomer makes a prediction shared by no one else in the world: at the stroke of noon on June 30 of that year, a solar eclipse will cast all of Europe into total darkness for four seconds. This astronomer is rumored to be using the longest telescope ever built, but he is also known to be blind. Is he mad? Or does he have an insight denied the other scholars of his day? These questions intrigue the young Gottfried Leibniz—not yet the world-renowned polymath who would go on to discover calculus, but a nineteen-year-old whose faith in reason is shaky at best. Leibniz sets off to investigate the astronomer’s claim, and over the three hours remaining before the eclipse occurs—or fails to occur—the astronomer tells the scholar the haunting and hilarious story behind his strange prediction: a tale that encompasses kings and princes, family squabbles, obsessive pursuits, insanity, philosophy, art, loss, and the horrors of war.

Sachs joined Andrew Martin, author of Early Work, at Harvard Book Store to discuss the writing process, melding genres, and building a nested story structure.

Andrew Martin: This book is extremely funny and excellent. I just want to make sure that I say this. I’m going to say this seven or eight times—it’s honestly one of my favorite books that I’ve read in a very long time.

Now, I wanted to start by talking a bit about historical fiction and how we understand it versus how you understand it. You studied history of science at Harvard, so you know your science very well.

Adam Ehrlich Sachs: Well, I quit. So I don’t know how much I know.

Martin: But you knew a little bit, at some point.

Sachs: A little bit.

Martin: And this book—when you look at it—it looks in some ways like a classic historical novel, an overlooked episode in the history of this famous philosopher and mathematician of Leibniz. As you read it, almost immediately you start wondering, “Wait, is any of this true? Is this true? What is true? What isn’t true?”

How do you think about the history that you’re using in the book? Do you think of it playfully? Do you think of it as just a scaffolding? How do you think about history in this novel?

Sachs: I’m trying, generally, to fool myself into believing what I’m writing—and that I should be writing at all, that writing isn’t some self-indulgent thing. Which of course it is. I think one way of helping me get around my own disgust with fiction is to exploit facts, to start from facts. Though in conceiving the book I didn’t actually start with Leibniz. The image I had in my mind was of an astronomer building a set of increasingly long telescopes—that felt worthy of a novel, for some reason. I wanted to write about solipsism, and it occurred to me that the problem of solipsism and the image of these increasingly long telescopes were in some way related. Leibniz came later in the process, to provide an ersatz historical frame, a veneer of fact, a way to get into the fantastical stuff I wanted to do.

I have no interest in getting anything right or accurate, and every time that I felt that urge, the urge to check something, I knew that the book had taken a wrong turn. I want to get to that surreal, fantastical place, but for some reason, I need to get there logically, reasonably. It’s a temperament thing. So that’s kind of how I use history.

I want to get to that surreal, fantastical place, but for some reason, I need to get there logically, reasonably.

Martin: It makes it so much funnier that it’s Leibniz, that it’s this particular person in history. The book takes part in this genre—it feels like a legend almost. Did you think about that, about the genre or what form the book takes?

Sachs: Yeah, I had three genres that I felt I could mash up. First, I kind of wanted a fairy tale: a guy walks up a mountain and has some experience up there and then walks back down. It’s a bit biblical, a bit fairy tale. Then I also like a good rambling, absurdist monologue. I figured I could mash the monologue thing onto the fairy tale thing in some way. I was also reading some nineteenth-century German novellas. They all use frame narratives, which now seems like a very old-fashioned thing, in a way. Like, you see a stranger every Wednesday and he has a slight limp, and then at some point, you sit down with him over a beer and he tells you this story of how he got this little limp. That’s kind of how all those novels felt.

Martin: It’s always something really horrible.

Sachs: Yeah, right. You go a long way around to get to this little limp, but in the course of it, many people die. First, it’s a nice way to create suspense—I don’t know if I’ve done it—but you want to figure out how this little thing happened. I feel like frame narratives have been made fun of—that sort of creaky, dubious Stefan Zweig thing.

Martin: I’m thinking of Titanic.

Sachs: Exactly. But I think you can rescue something by overdoing it, so I have a lot of frames. I’m trying to bring frames back.

Martin: Can we talk about the nested structure of the book? Because as you read this book, the feeling you have—at least I had when I read it—is just, how did you do this? How did you build this machine? Because there are stories within stories within stories, but it’s never confusing; it’s always clear.

As you go through it, it gets deeper and deeper, and there are moments where it’s “as Leibniz said to the astronomer said to his father said to his son.” It’s four or five layers of recounted speech, and there are a couple of scenes where people are singing these songs that have these refrains. It’s a little bit like “and the dog bit the cat, and the cat bit the bee, and the bee bit the thing.” And it goes on and on and on like that, but I wonder: Did you set out to do that? Did you get taken by the momentum of the story as you went along? How deliberately did you create this hall of mirrors?

Sachs: I started with that one image—the longer and longer telescopes—which I do get to at some point. I certainly didn’t start out wanting this very complicated contraption of narrators. At the end, and of course I’ve now done this with both of my books, I developed a very elaborate mechanism to justify the philosophical necessity of the different forms I use, but it started with the embarrassment of telling a story directly: Who is telling this? Why do I have the authority to tell this story? Who am I fooling? And, of course, again, this is Thomas Bernhard, this is W. G. Sebald—there’s a tradition I was working within. And then also—what’s that Susan Sontag line? Every writer needs four things: You need to be a moron. You need to be an obsessed person. You need to be a critic, and you need one other thing.

Martin: Did she not specify the fourth thing?

Sachs: Let’s say the fourth thing is left to your imagination. The fourth thing is a choose-your-own. Anyway, it helps me to keep those first three (moron, obsessed person, critic) distinct. It helps me to separate out the moronic part of myself from the more critical part—to invent a crazy person who would tell his story to a more reasonable character, and then have that story “translated” into English by an even more reasonable narrator. So I keep the moron and the critic apart, to prevent the critic from stifling the moron. And if the moron meets an even crazier character, so the story can free itself up even more, all the better. Also, this proliferation of narrators, each a kind of distorted reflection of the last, felt appropriate for a book about solipsism.

Martin: Talk more about that. What do you mean it’s about solipsism? Can you define solipsism for the dumb people in the audience like myself?

Sachs: It’s the question of knowing whether you can know anything outside your own head, the fear that the external world is some sort of projection of your own mind, which is part of what brought me to Leibniz: He’s an idealist, of a kind. Part of the way I was thinking about the book was as a kind of alternative genealogy of solipsism in the seventeenth century. My interest in all this came out of one week of freshman year of high school where I went into a fugue state and was convinced that everyone else was an automaton. Eventually I snapped out of it. But I realized there was no way to reason my way out of it. You could go through your whole life thinking that way, waiting to snap out of it.

My interest in all this came out of one week of freshman year of high school where I went into a fugue state and was convinced that everyone else was an automaton.

Martin: So, this book is a work of nonfiction?

Sachs: Yeah, this is a real freak-out. And then again, before my general exams in the PhD, I had another week of this. It’s a problem that kind of obsesses me. So, the nested narrators—you have no access to their minds, or to the facts they’re relating. You have access only to this other person’s mouth and the words that are coming out of it. And I was not at pains to differentiate the voices; they’re somewhat differentiated, but they’re all presented as one person meeting the next, or rather, reporting that they’ve met the next one, so you come to question if that second person is a real other person, because the voices can sound the same or bleed into one another.

Martin: The book opens with Leibniz having sent this paper into the philosophical journal where it was never published, there or anywhere else. So we’re immediately wondering: If it was never published there or anywhere else, how does the narrator know any of this? Who do you imagine as the narrator of this book? Do you imagine a madman at his desk with papers piled to the ceiling? Or do you imagine a clean-cut young man in Pittsburgh?

Sachs: Can’t it be the same?

Yeah, I guess I’m more comfortable in the scholar mode, even though I quit that. So I imagine some Leibniz scholar gone to seed who has some document on his desk that he either wrote himself the day before or which he found—he can’t quite remember. And he’s about to translate it.

Martin: Translating a document that he wrote himself, earlier that day.

Sachs: Yeah. That’s his life now.

Martin: You talk a lot about writers, some of the recent past who you read and some of the more distant past. People that I sort of detect are Barthelme, a little bit. I think we’ve talked about Nicholson Baker. Are there contemporary writers that you think about? How do you situate this book, in your own head, in the contemporary fiction landscape?

Sachs: I guess I think in terms of hatreds, who’s getting it wrong.

Martin: Who’s getting it wrong?

Sachs: Well, I think a lot of today’s so-called interesting writers are writing in the Thomas Bernhard vein, but I think they’re all getting him wrong. I feel competitive and worried about the number of people doing that, because of course I’m doing it, too. It’s been connected to the autofiction thing, because they all end up writing—because Bernhard, towards the end of his life, was always writing about a novelist in Vienna who has just come from a terrible dinner party, and I think the descendants of him do the same. But his early stuff is like weird Gothic; it’s in castles, people are disfigured, it’s quite different. I don’t feel any sympathy for or traction with autofiction. I just can’t write about myself—or I only want to do it in the most roundabout way possible. So, Bernhard without the Bernhard, I guess.

Martin: So these books are kind of a direct challenge to the current reigning, most popular fiction writers?

Sachs: That’s right.

Martin: I like it. It’s about winning, in my mind, as a fiction writer.

Sachs: Of course. Why else would we write?

Martin: I wanted to talk—and you mentioned your first book, Inherited Disorders, which is also a really great book. It’s a series of over a hundred very short parables and stories and they have similar structures, in some ways, to this book, but they’re miniatures. And this book, it’s an incredible expansion of that sort of tale or parable style. I wonder how you view the relationship between these books and how you—because I’m trying to write another book right now and it’s driving me crazy—thought about starting a second book and thinking about its relationship to the first book. Should it be more different? Should it be less different? How do you think about it?

Sachs: Are you writing a novel now or short stories? Which crazy are you experiencing?

Martin: Well, I wrote a novel and then stories. Now I’m trying to write a novel. I should probably just do the same thing over again—I don’t know.

Sachs: The third one is—that’s really painful. I think I’m probably ambivalent about this like I’m ambivalent about everything. The authors I like, all their books are very similar and they have one theme and they go at it again and again. So I think I should be pleased when I hear that they seem cut form the same cloth, but of course I feel angry when I hear that.

Martin: They feel in the same universe.

Sachs: Same universe—yeah, that’s a nice way of putting it. But I have the image in my head of one of those little bath sponges, and you pour a little water on it and grows a little bit and becomes a little soggy, and that would be the bad version of the way this novel relates to the short stories.

Martin: This is what it looks like in the commercial when it all of a sudden takes up the whole bath tub.

Sachs: Yeah, this novel is how those sponges should work and don’t.

In certain parts of the book I feel like I’m playing with the same father-son structures. But in the first book, I couldn’t get beyond the very short half-page or page, and here the use of monologues helped me fill up pages in a different kind of way. I think the sentences got more complicated, for better or worse. Some different things are happening, I hope.

Martin: No, they are. And what I was really impressed with in this book is that it’s very funny and it’s this kind of this incredible—two different people, including myself, used the word “madcap” in blurbs for the book.

Sachs: Yeah, I wanted to separate those madcaps. There were too many madcaps, but that’s how they printed it.

Martin: What I wanted to say is that what’s really amazing is that it comes from this place of real pathos; the book feels like there are real emotional stakes. This astronomer—who we assume is mad—you do such an incredible job of inhabiting the character and making us wonder, “Well, maybe he’s onto something. Maybe he really has figured out how to be this incredible, blind astronomer.” Something about it keeps you hooked in. So I wondered how you thought about creating realism in a sort of fantastical landscape, and how you do that. How do you think, specifically, about how to stud it with detail that makes it feel real, that makes the characters come home to human behavior? How do you think about that?

Sachs: I guess it’s part of the project of not having any historical accuracy at all. The characters—I think of them as people I know, just with really ridiculous seventeenth-century wigs. I think of them in a very artificial way. Basically, I include my own concerns, my own people. For some reason, dressing them up let me exploit my own concerns in a more direct way than I think I could’ve if I were writing about these things directly, so I did not have to feel my way into what someone might have been thinking in Baroque Leipzig, what their concerns would be, how they felt about their buckle shoes.

The characters—I think of them as people I know, just with really ridiculous seventeenth-century wigs.

Martin: The old-timey stuff.

Sachs: Yeah, right.

Martin: Have people recognized themselves in these costumes?

Sachs: I’m not sure how many people have read the book. But it’s a good test.

Martin: You know who they are.

Sachs: Yeah, and I’ll know the moment they read the book.

Martin: When you’re writing autofiction, like some of us, you get a lot more direct questions about these things.

Sachs: Yeah.

Martin: How long did it take you to write this book? What was the actual composition process?

Sachs: For a year and a half, two years, it was in the phase I’m in now, of just restarting again and again. So far both books have taken me, like, three years: a year and a half of writing and a year and a half of not producing any work, just suffering. Then, at some point, I got the first sentence, and I felt like the whole book was contained within it. Then I could write the rest of it. The writing was fun, but the first year and a half, which I’m in again now for the next book, is not fun.

Martin: I think if there are no rules, it can be really, really hard. I won’t name names, but some fantasy—not fantasy, but some fantastical magical realist stuff—you have no idea what the stakes are or where the world is, so it becomes sort of . . .

Sachs: Weightless.

Martin: Yeah, it becomes sort of weightless. And I feel like if you have some reality in it, then you can build from there rather than being in an up-in-the-air place.

Can you talk at all yet about what you’re working on next, or is that just not allowed?

Sachs: Yeah, no, sorry . . . Can you?

Martin: No! But for me, it’s going to be more like, “a guy walks around, talks to some local people.”

Sachs: Me too, I just need to pick the century.

Adam Ehrlich Sachs

Adam Ehrlich Sachs is the author of the collection Inherited Disorders: Stories, Parables, and Problems, which was a semifinalist for the Thurber Prize for American Humor and a finalist for the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s Magazine, and n+1, among other publications, and he was named a 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellow. He has a degree in the history of science from Harvard, where he was a member of The Harvard Lampoon, and currently lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Andrew Martin’s stories have appeared in The Paris Review, Zyzzyva, and The Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly, and his non-fiction has been published by The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, Harper’s, and other publications. He has received fellowships from the UCross Foundation and the MacDowell Colony. Early Work is his first novel.