This week’s edition of Work in Progress celebrates Pride Month. We asked ten of our authors to reflect on a foundational queer text in their life—works that influenced their writing, style, or path as an artist. In their responses we see a wide range of queer experiences and worldviews, a stark reminder that queerness is not a monolith. From Alice Walker to Willa Cather, from the search for visibility to the “disturbingly radical,” from the Harlem Renaissance to the “sci-fi sexscapes of Ba’dan,” here are their responses.

Mark Gevisser

Author of The Pink Line: The World’s Queer Frontiers

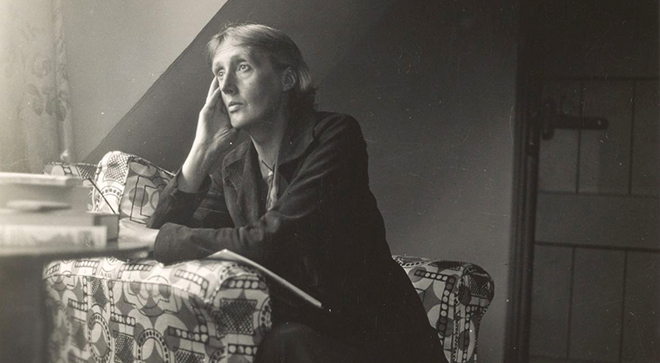

Edmund White’s A Boy’s Own Story and James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room were my teenage anchors, as I turned to books to try and understand who I was. But my queer foundations are in Virginia Woolf, and in particular in a seminar I took in my sophomore year at Yale in 1984, with an incomparable guide named Patricia Kleindienst. Woolf’s sentences opened new possibilities for me, as a writer and a human being, in the way they went behind the spoken words, charting the distance between what is felt inside and what is seen. This is at the core of queerness today, particularly when it comes to gender identity and expression, but Woolf was on it seventy years ago: from Orlando, with its gender-fluid protagonist, to my favorite, The Waves. Here she brings us the openly homosexual Neville, published only thirty-five years after Oscar Wilde went to prison; here she expresses one consciousness through six voices, three male and three female, in a subterranean thrum that has become my soundtrack.

Roya Marsh

Author of dayliGht

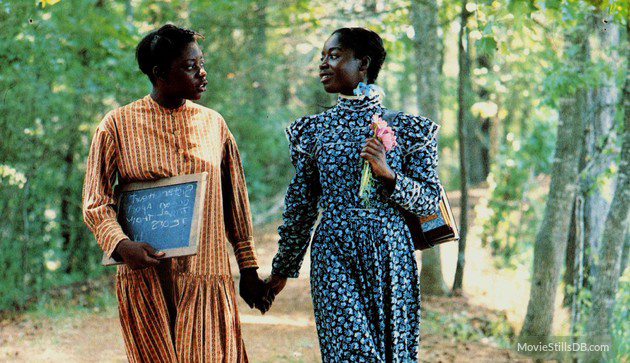

Growing into queerness in a heteronormative all-girls catholic high school was a journey for the ages. In a desperate search for representation, past and present, a mentor passes me a copy of Alice Walker’s The Color Purple. It is 2004, I am a sophomore in high school and have few, very vague memories of the 1985 film adaptation which I had seen (and not comprehended) as a young child. Walker’s vivid depiction of intimacy between Celie and Shug Avery drew my fifteen-year-old mind right into the storyline. The Black gay female experience is illuminated in a way that humanizes an otherwise seemingly powerless character. This love is the bridge that allows Celie to access her true strength and will. It does away with the idolization of whiteness and uplifts a romance that the world is still attempting to erase. The voyage toward Black lesbian visibility continues and we are ever ready for the trek, in fact, “I think this the youngest us ever felt.”

Shelly Oria

Author of New York 1, Tel Aviv 0

In the summer of 2003 I was getting ready to move from Tel Aviv to New York when a renowned Israeli writer named Yehudit Katzir published a new novel about a teenage girl having an affair with her teacher, a married woman in her late twenties. (The book was later translated into English and published by the Feminist Press as Dearest Anne.) It was the most subversive, radical book I’d ever read, at once disturbing and sexy, and I spent two days reading it when I should have been packing. The experience expanded my understanding of how eroticism could be captured in literary fiction, and in some ways expanded my understanding of my own sexuality. Back then, texts could easily become “foundational” in my life, seeing as I was still actively shaping my foundation—both as a writer and as a human in the world. But countless other queer books I’ve read over the years have affected me deeply, so I’d love to mention a few more. Anyone coming out to their family or wanting to support a loved one through that experience should read Sarah Schulman’s Ties that Bind: Familial Homophobia and its Consequences. Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the weirdest books I’ve ever read and one of my favorites for how nonchalantly it treats its own weirdness, and its characters’ elastic, ever-changing sexuality. And T Kira Madden’s Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls will break your heart and put it back together, stronger and queerer.

Darryl Pinckney

Author of Black Deutschland

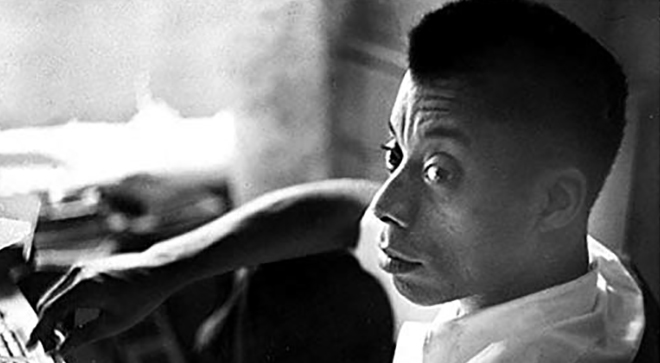

Our high school German teacher, Herr Brown, was so good at his job most of the class did very well on the Advanced Placement exam senior year and several of us would be excused from the language requirement once we got to college, which in my case was a mistake, because I should have kept on studying German. An elderly gentleman, though he probably wasn’t at the time, he just seemed so, because he was bald, Herr Brown lived with his mother. I knew from the passionate way he talked about Der Tod in Venedig and Tonio Kroeger that he, Mann, and I shared a secret. But it was not going to be any of the married guys, Thomas Mann, or Andre Gide, or Verlaine, that I would fall for once I got to college. I didn’t speak French and Rimbaud intimidated me as much as the cool people who swore by him.

Suddenly, there was so much. The Elizabethans were queer, not just reliable old Oscar Wilde or assorted Yellow Book Victorians. Bloomsbury was queer and so, too, poets in the trenches of World War I. Back on this side of the pond the Beats were crazy gay and so was a lot of The New York School. Mishima, Rechy, and Gore Vidal were names that had an aura of being notorious. The Harlem Renaissance was queer, but it would take a long time for people to talk truthfully about “Uncle Lang.” This left James Baldwin in rather splendid isolation. Remember Henry van Dyke? Baldwin wasn’t discussed as a gay writer, though his novels were full of queer love. It’s just that race had a way of upstaging same-sex matters when his novels got talked about. Giovanni’s Room was the brave exception, the cast of characters being white. I’d read it in a state of adolescent incomprehension, much as I had the sexy parts of Zola’s The Restless House. Baldwin’s novel is full of beautiful writing about love, but it is also of its period and queer love is over before Giovanni is taken to the guillotine.

I discovered Christopher Isherwood through the film Cabaret, an obsession that took me quickly to the source. I have this memory of sitting up all night in study hall reading The Berlin Stories and Prater Violet instead of finishing a desperate term paper. It was winter; I was alone. I looked out at the campus lights and wished for Weimar decadence and to tangle with Otto’s sullen Nazi brother. Isherwood, the observer of his own scene, in the middle of Berlin, but exempt-seeming, because of his foreignness. I never felt a code at work in The Berlin Stories. Isherwood lets Sally Bowles decide that Christopher would be entirely unsuitable as a boyfriend, and then he gets on with doing what he wants, and it didn’t need a name, it was so clear what was going on, class dynamics and all. Yet Isherwood’s narrator is free in a way that, as I look back, I see was very important for me to take in. German history is the tragedy in his stories, not queerness.

Chris Rush

Author of The Light Years

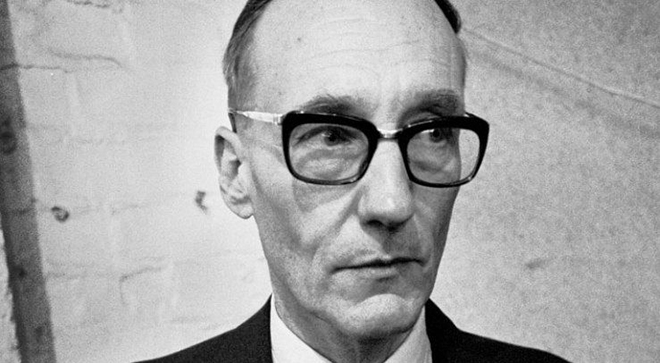

Summer of 1981: I’m twenty-five and William Burroughs’s Cities of the Red Night falls squarely into my lap. It’s a shock, and a revelation: pirates flying across the desert, crashing down on the sci-fi sexscapes of Ba’dan. No disco, no lip gloss, no feathered hair—just an outlandish queer adventure. A month later, I move to New York City to look for pirates and Bill Burroughs.

Katrina Carrasco

Author of The Best Bad Things

Ali Smith’s How to be Both is one of my most beloved books. In it, Smith’s writing is generous, poetic, and full of wonderment. Queerness is the default rather than an anomaly (such can be the effect of well-wrought queer main characters). The book is excellent on its own, but it holds special meaning for me: it was recommended to me by my partner on our first date and, after wandering through a bookstore together, I bought it then and there. I read it as I was falling in love with her, and now the book is forever infused with that springtime—unfurling flowers, long dreamy mornings, the sweet air fizzing with possibility.

Nicola Griffith

Author of So Lucky

Molly Bolt, the hero of Rita Mae Brown’s ovular lesbian picaresque, Rubyfruit Jungle (Daughters, Inc., 1973), is a kissing cousin to the Mary Sues of fan fiction. Born poor and illegitimate, she’s so smart, so beautiful, so witty, confident, and sure, that she almost always gets her way and she’s never in real moral or physical danger—and, oh, how I liked that! I fell on this book, gulped it down like a starved wolf, threw back my head and howled: See! Dykes can so too be gorgeous, witty, and swaggeringly sure they’ll get the girl! Brown can write, the sex is hot and the emotions true, and though it was set in a world I’d never seen, Molly’s interior life felt real enough to become an instant archetype. The tropes Brown created in 1973—first love with a bisexual who abandons Our Woman; overcoming the heartbreak; making a new start (new job, college, depending on narrative era); getting kicked out for being queer; some kind of kinky sex-for-money interlude while living wild on the streets and/or exploring lesbian subculture; a queasy-making relationship with an older woman; meeting The One and living happily ever after—still ring through subsequent lesbian coming out novels, whether published shortly thereafter (Kinflicks, Lisa Alther) or more recently (Tipping the Velvet, Sarah Waters). Funny, moving, and occasionally erotic, it’s a documentary record of both how attitudes change and how so much about the human heart—and other organs—stays the same.

Walt Odets

Author of Out of the Shadows

I don’t know that there is a single “foundational queer book” that gave birth to my experience as a gay man, or defined my perception of gay communities and what it means to be gay. But, Michael Warner’s The Trouble with Normal (1999) is an important book, and one that is consistent with my own non-assimilationist hopes for gay people. In my recent book, Out of the Shadows, I say, “All the diverse forms that true gay life has improvised constitute a special universe that should not be relinquished to the meet the expectations of a pathological society.” Personally, I’d rather have a Queer Parade than a Pride Parade.

Sarah Schulman

Author of Let the Record Show

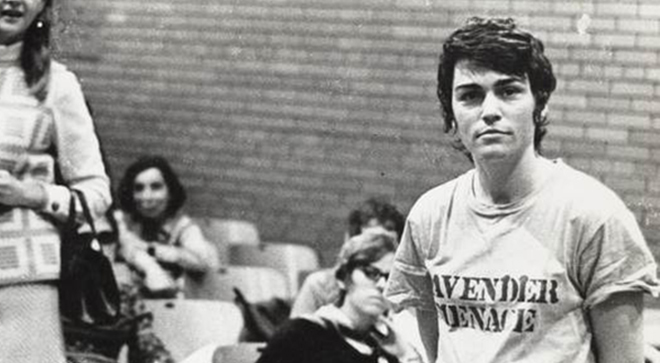

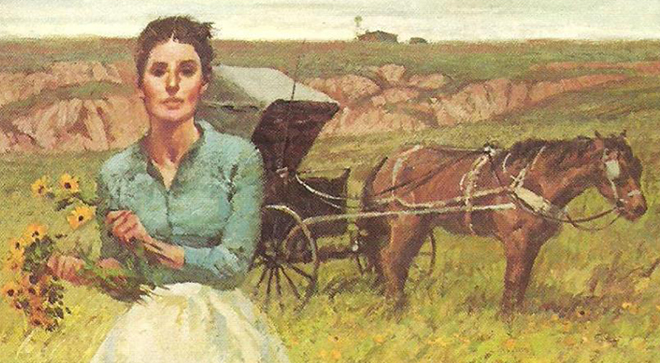

There are so many: Willa Cather’s My Antonia—employing the convenient device of the person on a train telling the story of the woman “he’d” loved, Antonia. A Nebraska with the houses full of cowboy couples, sleeping together, making cucumber salad, and in a dark and stormy night feeding the straight newlyweds to the wolves—reminding us that cowboy was a very homosocial profession and a great reason for a queer young man to leave the compulsory heterosexuality of genteel East Coast life.

Novels that I return to over and over again: Thereafter Johnnie by Carolina Herron, I, The Divine—a brilliant work by Rabih Allemeddine, whose earlier Koolaids: The Art of War is one of our strongest AIDS novels. I loved Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s Sketchtasy, my favorite novel of 2018.

I am currently writing a film based on the life of Carson McCullers, Lonely Hunter, and all her books have queer, lesbian, and trans foundations. Thinking of the Singer, the gay Jewish mute of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, Mick and Frankie—Carson’s tomboy/trans dopplegangers, the gay Fillipino house servant of Reflections In A Golden Eye, and Miss Amelia’s queer love in The Ballad of the Sad Cafe.

In theater, I would say Cherry Jones’s very lesbian performance of “spinsterhood” in The Heiress on Broadway, where the marginalization and torment of heteronormativity makes her very, very clear, focused, brilliant, and victorious. Or those scenes in Bertolucci’s The Conformist between the married lesbian Dominique Sanda and her young object, the fascist’s wife, who she takes dancing across the ballroom floor.

In nonfiction, of course, nothing beats Tennessee Williams’s memoir, Memoirs, which defies all rumors of dissipating talent at the end of his life. It is energetic, funny, moving, and honest: every hustler, every Quaalude, and every blowjob. My college professor at Hunter, Audre Lorde’s essay “The Transformation of Silence Into Language and Action” is the most teachable essay I have ever read. I have yet to come across a student who cannot relate to it. Book I am most looking forward to: Poor Queer Studies by Matt Brim, coming from Duke Press in 2020.

Susan Stryker

Author of Changing Gender

Anthropologist Esther Newton’s Mother Camp, an ethnography of “female impersonators” in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s, was the first book I ever read that did not treat gender variance as pathology. As a college-aged trans-identified person in the late 1970s and early 1980s, I was desperate to find information about people like me that didn’t treat what we’d now call “transgender,” broadly defined, as an abberation or a malady. Whenever visiting a university library, I’d scour the card catalog (remember those?) for any relevant books, and found Newton’s at the University of Texas at Austin, around 1980 or 1981. While I never considered myself a female impersonator, Newton’s book was a revelation—rigorous, non-judgemental, with wit and flair. Newton has always been my model for what a queer academic can be.