It goes without saying that even today, it’s not easy to be gay in America. While young gay men often come out more readily, even those from the most progressive of backgrounds still struggle with the legacy of early-life stigma and a deficit of self-acceptance, which can fuel doubt, regret, and, at worst, self-loathing. And this is to say nothing of the ongoing trauma wrought by AIDS, which is all too often relegated to history. Drawing on his work as a clinical psychologist during and in the aftermath of the epidemic, Walt Odets reflects on what it means to survive and figure out a way to live in a new, uncompromising future, both for the men who endured the upheaval of those years and for the younger men who have come of age since then. Out of the Shadows is driven by a belief that it is time that we act based on who we are and not who others are or who they would want us to be.

Odets joined FSG President Jonathan Galassi to discuss the turbulent history of gay self-acceptance, shame, and the experiences that most informed Odets’s work on the book.

Jonathan Galassi: Let’s begin at the beginning, Walt. You’ve worked with gay patients in your work as a therapist all your life. What made you decide to write this book?

Walt Odets: About twenty years ago, beginning shortly after my first book, In the Shadow of the Epidemic, was released, I came to feel that too much of what was important in any discussion of gay lives had been left out. I wanted to write about those issues because I was seeing them crop up daily in my therapy work, and in my own life. The problems in actually getting to the new book were legion, mostly connected to the ongoing epidemic, the trauma it had forced on so many men, and for me, the grief I felt about the death of the man I had loved more unequivocally than anyone else. I started making notes on the various things I wanted to talk about in a new book, but I balked at the specter of having to actually sit down and write about things that would make me cry. Around 2013, I found two large boxes of notes, and my first thought was that I needed another box. The second was that I should buy a big case of Kleenex and just sit down and write about the issues and cry if I needed to, which is what I did.

I balked at the specter of having to actually sit down and write about things that would make me cry.

Galassi: Tell us what you mean by “the ongoing epidemic” and how you feel it has affected your patients’ and friends’ lives.

Odets: In 1996, with the introduction of new drugs and drug combinations—we called them HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy)—we had an inkling that after fifteen years we might actually be able to curb the deaths. About 300,000 gay men had died of AIDS at that point—a huge number for such relatively small communities. But with HAART people kept dying, and after all the years of treatment failures, it took a long time for anyone who had been through the earlier years to have any real confidence. So the epidemic was ongoing both medically and emotionally. I, my patients, and my friends had lived through a huge trauma. That’s not something one walks away from simply because it’s allegedly over. The New York Times ran a cover story in the Sunday magazine—in 1996, I think— titled something like “The End of AIDS.” It was ridiculous, and it made a lot of people angry. It would be as if your house—and every meaningful thing you’d accumulated in it—burned to the ground, and when the fire is finally quenched, everyone tells you that you should just go on with your life. With such experiences, there is a serious emotional aftermath. This was true for both HIV-positive and negative men. Trauma doesn’t just vanish when its source is gone. It was years later, maybe 2002 or 2003, six or seven years after HAART, that I started to feel that maybe I and my friends would survive—for a lot of people, it took time to feel that they wanted to survive.

Galassi: I have friends who lost friends and lived through that time of tremendous anguish who never refer to it, as if it didn’t happen.

Odets: There’s a lot of denial and repression following any experience of trauma. There’s the feeling that you’d like it to have never happened, and the best way to make it not have happened is to not remember it. It feels like the only alternative is hysteria or depression, or both. Denial and depression do protect people from emotional pain, and to some extent it works and is helpful. Now I’m speaking as a psychologist—the problem with denial, and particularly with repression, is that it acts globally, both in one’s internal life and one’s life as a whole. It constricts and depletes a life of emotion and vitality, and I think in many instances it makes intimacy and love impossible. I have friends like the ones you’re describing, and I would never confront them with what we’re talking about here because it’s none of my business and I’m not their psychotherapist. But in my experience, there is usually something incomplete about them, something not quite whole. It’s something I focused on in the book, particularly the middle ground between living in hysteria and depression and forgetting that it ever happened. There’s a huge middle ground there.

Galassi: One of the things that struck me deeply in the book, one of the most moving things I’ve read about in a long time, is the enduring issue of shame in gay lives.

Odets: We have to start with the shaming by others that is at the root of self-experienced shame. A man once told me that at the age of sixteen his father asked him why they couldn’t spend more time together, to which the teenager responded, “Because you’ve made me hate who I am.” Being gay, like being straight, is about nothing more or less than the almost universal human need for “attachment”—which is to say emotional connection, the attachment we first experience in infancy and childhood, and perhaps even in gestation—I mean, how attached can you get? As we get older, gay people, for many different reasons, are more inclined to attach emotionally to same-sex others, and to sometimes express that attachment sexually, all of which seems to me to be an expression of natural human diversity. But when the expression of that diversity is stigmatized by others—particularly by the immediate family—the gay child or adolescent internalizes the stigma, and feels shame about who he is.

Being gay, like being straight, is about nothing more or less than the almost universal human need for “attachment”—which is to say emotional connection.

The core objective of shame is to prevent one from being seen or known by others. And this shame is not just a feeling about particulars, it quickly becomes an entire internal identity. One not only feels shame, one becomes a “shameful person” who cannot allow others to know him. Without being known, there is no authentic attachment, and the result is often a pragmatically contained and truncated life, and an emotionally impoverished one. And loneliness, isolation, and self-harm can easily become part of that life. Shame is very destructive, and it needs to be talked about. Gay pride has dictated that there is no shame, which is simply untrue—particularly in the face of difficult family relations.

Galassi: How do you see these issues playing out in the lives of younger men? Our culture, at least on the surface, has become much more tolerant of sexual difference.

Odets: Think of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation from something like 150 years ago. Are black people better off today? Yes, of course, but there’s still an inexcusable amount of hate and prejudice directed at them. I think something similar is still very much the case for young gay men today—the problem is mostly still there. I have to mention again that the immediate family, and particularly parents, have the strongest influence on how LGBT people experience themselves. Legislation in support of gay people is good, but hardly a complete solution, and there’s not even enough of that. So, if the criterion for tolerant families is educated, sophisticated people who live in Manhattan, believe most of what they read in The New York Times, and subscribe to the New York Review of Books, then yes, things are much better. But forget about Staten Island, and a lot of Queens, and the Bronx, and don’t even mention Indiana or Wyoming. Much of the U.S. is “Staten Island,” and young people are still stigmatized by families and communities.

What has changed for many young gay men is that they come out more readily than they used to. They have the internet and other media, and they now know there are millions of other gay people, and that they’re not unicorns. But simply coming out—which is often a push back against stigmatization—is not a good predictor of true self-acceptance or the quality of a life. Even when young men move to gay communities, they have problems relating to others, in part because stigmatized people are likely to project their own shame onto others—something like, oh, I’m not the fag, he is, and I don’t want anything to do with him. We’ve seen this with the recent introduction of highly effective drugs to protect HIV-negative people from contracting the virus. Gay men have been calling each other “sluts” and “whores” for using the drugs, because the sluts and whores want to have sex. This is an expression of shame, but it is couched in denigrating words like “promiscuity.”

The other difficulty that young men are finding in gay communities has to do with divisive community politics. A significant component of gay communities seeks the social tolerance you speak of through assimilation into the mainstream culture—getting married, having children, fighting in Afghanistan. In this model, tolerance is based on gay people acting and living like everyone else, or at least looking like they’re doing that. A lot of young gay men have no interest in that solution, and they find themselves stigmatized not only by families and the culture of Staten Island or Indiana, but by other gay men within what are supposed to be “gay communities.” They find that they’re still outsiders, and the result is a lot of isolation and loneliness.

So yes, there is a shift of values in some small enclaves in the U.S., but that’s not nearly the whole story. I have an early-twenties man in therapy right now. A year after moving to San Francisco, he announced to his parents—on Facebook—that he was gay. His father did not respond, but his mother sent a flowery pink and green greeting card, which said something like this: “I know there are a lot of homosexual people around, and you’re going to be whatever you want, but I don’t want to hear any of the disgusting parts about sex and the like. Love, Mom. P.S. Aunt Beth is having a hip replacement next week and you should send her a nice card.” End of novella.

Galassi: In the book you talk about the difference between the terms “homosexual” and “gay”—“homosexual” referring to sexual behavior, and “gay” to a much broader and deeper attitude to life itself. I can remember feeling a generation or two ago that being “gay” was in many respects a way of voting against hetero-normative culture. How do you see these distinctions today?

Odets: The idea of the homosexual as a complete characterization of a person is a nineteenth-century invention. It was launched in a book published around 1880 for medical providers, titled Psychopathia Sexualis—sexual pathology—written by an Austro-German psychiatrist, Richard von Krafft-Ebing. In his construction of things, men who had sex with men were no longer simply individuals who engaged in certain sexual behavior, they were men who were completely characterized by that behavior. These men became “homosexuals.” I dispute the term “homosexual”—which Krafft-Ebing discussed as a pathology along with pedophilia, necrophilia, sadism, and many others—because it is not in any way a pathological condition, and because it supports a very narrow perception of a man who feels emotional attachment to other men, and sometimes expresses that sexually.

The unhappy consequence of the homosexual identity is that too many men, even today, internalize the identity and feel that love, relationships, and emotional intimacy have nothing to do with sex, and that sex is all that their lives are about. Being sexual becomes one’s self-identity. This is a ridiculous concession on our part. Gay men have a very distinct sensibility that is rich and complex, and offers the possibility of combining what are conventionally thought of as male and female sensibilities. That integrated gay sensibility is what truly defines realized gay lives, and sexual expression may follow, but it does not lead. In other words, people are not gay because they behave homosexually, they express themselves homosexually because they are gay. Sexual connections are a physical expression of the natural human emotional need for connection, emotional attachment, and shared intimacy. The opening chapter in the book is titled, “Are Gay Men Homosexuals?” The answer is no.

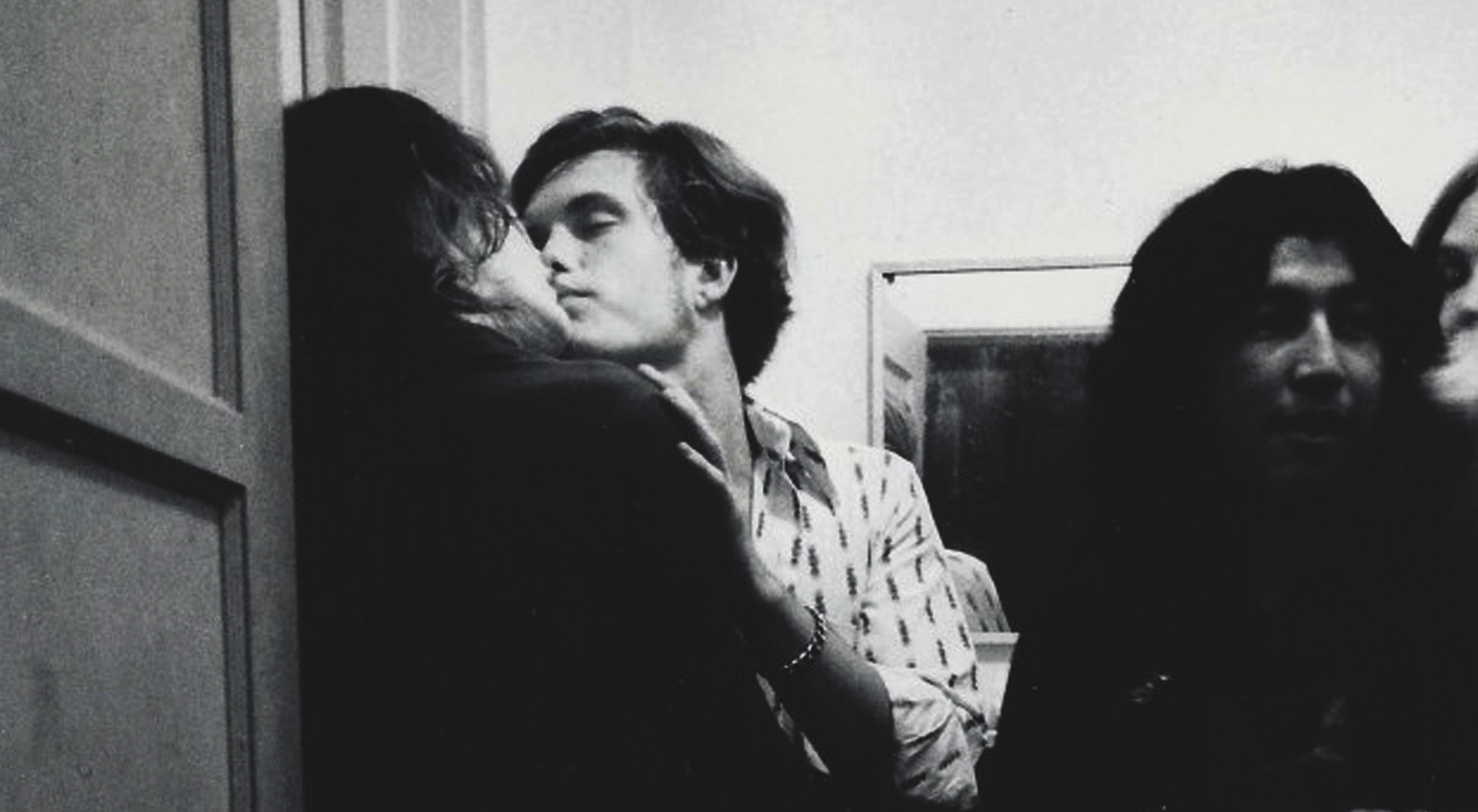

Today, the term “gay” is considered the respectful term, but in most people’s understanding it is still a euphemism for homosexual. Look up the term in any dictionary and you’ll find that the first definition is “homosexual.” Gay should be defined as something more like “homo-attached” or if one needs a psychological term, “homo-cathected.” Many think the term “gay” started in early twentieth-century America as a code word to protect identities. In its favor, “gay” does not explicitly begin with sex in defining a man’s nature, but it also doesn’t describe much else. And as you suggest, in later years it was adopted to allow men to assert their right to reject a heteronormative culture. We called that movement Gay Liberation. But even then it was significantly about men having the right to have sex with each other. In the 1970s, the idea that men do not fall in love and do not have “true” relationships was still widely accepted by gay men themselves because that was what they’d been taught. What was important about the term was that men took back the right to call themselves whatever they wanted, and that made it radical and non-hetero-normative. In my writing, I use the word gay to refer to the entire sensibility I mentioned a moment ago.

Galassi: Have you had experiences with lesbian patients? How do you think gay women’s experiences differs from men’s?

Odets: Some—maybe ten percent of my practice over the years. My limited experience is that lesbians and gay men share a great deal in terms of societal and familial stigmatization. Yet, as children, I believe that “boyish girls” are usually more readily tolerated than “girlish boys,” because American culture insists on the idea that masculine postures define competence and strength. This tolerance is particularly true for fathers, often less so for mothers. As they grow older, the experience of lesbians and gay men begins to diverge further. Adult lesbians can intimidate straight men, who often resent the competence and competition of women. Straight men can feel undesirable to lesbians. Many men are thus humiliated by lesbians, on several scores. The response often seems to be one of diminishment or dismissal of adult lesbians. For gay men in later years, I think the situation worsens on a steeper curve. America holds assumptions about masculinity that make “femininity” and displays of affection among men intolerable to many. Straight men often feel personally demeaned or threatened by the idea that other men have those characteristics, and by the idea that straight women can feel undesirable. Such confused internalizations of the meanings of others’ lives are clearly expressed in the idea that gay marriage demeans the meaning of “real” marriage. The concrete result of all this internalization, fear, resentment, and anger is that gay men are much higher than lesbians on the list for hate crimes.

Galassi: What are the crucial issues in enduring relationships among gay men? What do you mean when you say gay relationships are inside-out?

Odets: Let me try to answer your second question first. The larger society has always had a narrow model for human relationships—what it likes to think of as real or important relationships—and until very recently that model has excluded relationships between two men. The traditional “real relationship” model is about two people living together, bound by the implied terms of a government-issued license, which is essentially a contract that places on the couple expectations of eternal love, hell-or-high-water lifetime commitment, and inviolable monogamy. This hasn’t worked out happily for a probable majority of American couples, and it’s unlikely to significantly improve gay relationships. It’s an outside-in approach to relationships—socially defined relationships that require each of the participants to twist his or her inner life—of feelings, emotional needs, and personal growth—into something that sustains the terms of the contract. To me, this outside-in construction feels backwards, particularly for gay men who have long been outsiders, and have always had to invent their own relationships, starting from scratch.

Gay men usually grow up accepting the socially dictated outside-in model as a standard for relationships because that’s most of what they’ve observed, and because they’ve been told that men don’t really fall in love or have true relationships with each other. The internet and media exposure are now beginning to change that perception, but many gay men still wish to mimic the outside-in model, for many different reasons—including a legitimization of gay relationships that will hopefully confer societal and familial acceptance. My suggestion in the book is that we stick with self-invented, inside-out relationships that express and are constructed around our internal lives and needs. You wouldn’t know it from the political tactics of today’s gay communities, but gay men and gay couples are not “just like everyone else,” nor should we be. In many ways we’re different from heterosexuals, very often for the better. We have more complex internal lives—what I call gay sensibilities in the book—and thus more potential freedom in how we imagine and live out our lives. I’ve known many gay relationships that are fraternal, paternal, non-monogamous, polyamorous, or communal, and men should be free to explore these possibilities. These are inside-out relationships, relationships that express and accommodate our emotional lives, and they’re an alternative to having our emotional lives squeezed into someone else’s model of what a relationship should be.

The endurance of a relationship is valuable if mutual experience has supported its endurance, not because relationships are “supposed” to endure as the outside-in contract dictates. There are a lot of people, gay and straight, who are in long-lasting relationships and are miserable. I can’t accept that type of staying power as a useful measure of value. The conventional idea is that relationships last because of “fidelity,” and conventionally that means monogamy. In itself, monogamy does not make an otherwise troubled relationship worth enduring, and non-monogamy does not make it unworthy. I believe true fidelity is not about monogamy, but about honesty and respect, and the ability and willingness to communicate honestly and respectfully. Here—fidelity as honesty and respect—there is no difference between gay and straight relationships. Without honesty and respect, there is no trust. And without mutual trust you don’t have a relationship—you have an unhappy sparring match that only worsens over time.

Galassi: One of the most powerful aspects of your book, which involves so many layers of thought and experience, is the portraits of your patients, the depth with which you explore their inner lives. Do you see patterns of behavior and, even more, of understanding of self and culture that have evolved over time in the span of your work?

Without stigmatization, we wouldn’t have gay identities, we’d just be people.

Odets: Stigma and adversity define both group affiliation and self-identity, and for gay people this is all shifting, at least in America. Without stigmatization, we wouldn’t have gay identities, we’d just be people. In nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America, being gay was about being invisible for the sake of safety. Then, mid-century we had the Homophile movement, which was—very roughly speaking—about trying to get society to stop police raids on our meeting places and leave us alone. Then came the more assertive years of Gay Liberation in the ’70s, a sort of fuck-you-we’re-going-to-be-ourselves movement. And then, of course, the epidemic in the ’80s and ’90s, which necessarily brought gay men together. All of these periods involved bonding, and defined communities and provided a sense of both individual identity and belonging.

Gay communities today are much less coherent, divided between those who seek “normalization” and assimilation, and those who still want to be gay in a more independent and radical way. So, today I see a lot more of both young and older men who straddle the fence and don’t quite know where they fit in, or how to define and experience themselves. But in terms of the emotional experience, I’ve not seen much of a shift in the past thirty years working with gay men. Historical trauma and the immediate family are still the primary issue. The consequence of stigmatizing, rejecting, or abusive families still defines emotional lives. So does the psychological aftermath of the epidemic, a huge and overlooked issue. I think the stories of gay men told in the book—there are twenty-four of them—are stories that most men will recognize, and that many will feel I’ve somehow written about them.

Walt Odets is a clinical psychologist and writer. He is the author of In the Shadow of the Epidemic: Being HIV-Negative in the Age of AIDS. He lives in Berkeley, where he has practiced psychology since 1987.

Jonathan Galassi is the President of Farrar, Straus & Giroux.