This week’s edition of Work in Progress celebrates Women’s History Month. We asked nineteen of our authors to write about the women who influenced their writing, style, or path as an artist, and their varied responses speak to the way a person or work has the power to completely change one’s worldview. From Grace Paley to Jean Rhys, from a sister’s diary to a Latin teacher, here are their responses.

Virginia Woolf, Marianne Moore, Elizabeth Bishop, and more

Maureen N. McLane • Author of Some Say

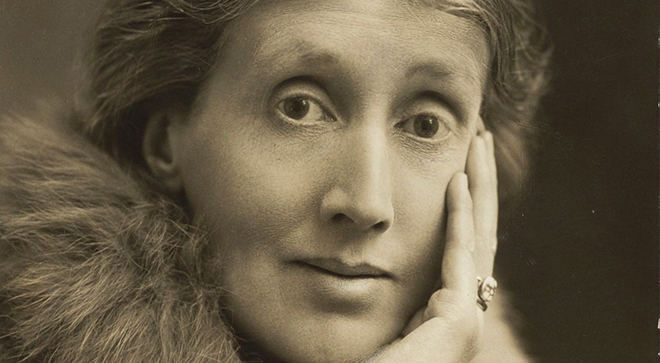

I write because others wrote: over many years, some writers and some works lodged in the ear and the mind and called me forward, backward, aslant. Sometimes they impeded me, productively: I’m looking at you, Gertrude Stein. If, as Virginia Woolf wrote, we think back through our mothers, I would want to acknowledge not one woman writer—though I could go on and on about specific writers and works—but rather a kind of chorus of poetic foremothers, and contemporary sisters, who have beckoned, shaped, provoked, inspired, and vexed me: the astonishing modernists H.D., Marianne Moore, and Gertrude Stein; Elizabeth Bishop; contemporary poets Anne Carson, Louise Glück, Fanny Howe, and Susan Howe, who I first read years ago; and younger poets like Anne Boyer, Tonya Foster, Cathy Park Hong, MC Hyland, Katie Peterson, and Donna Stonecipher. Also profoundly resonant: so many others, not only poets—including the masterly, subtle scholar of comparative literature, film, and the emotions Patrizia Lombardo; the formidable scholar of worldmaking and citizenship Elaine Scarry; the great queer theorist and scholar of affect Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick; and the brilliant classicist Laura M. Slatkin. And beyond this, alongside this, before this: Sappho in translation; Emily Dickinson; and Anonymous: for as Woolf (another core member of my inner library) wrote, “I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.”

The Works of Elizabeth Strout

Lisa Gornick • Author of The Peacock Feast

While Virginia Woolf, who showed us the fluidity of point of view and time, and Alice Munro, who can depict an entire life in a matter of pages, will always be goddesses in my pantheon, it is Elizabeth Strout who has most deeply left a footprint on my work in recent years. With Olive Kitteridge, I learned how stories can reverberate such that what we discover later in a book—or in life—creates a new experience and understanding of what came before, and saw the pleasure—is it innate?—of piecing together a world through many eyes and across many years. With My Name Is Lucy Barton, I was gob smacked by the breathing room—how much happens between sentences and in the white spaces—and how the conciseness at every level generates a compression of emotion. In her acceptance speech for The Story Prize Award for Anything Is Possible, a collection of stories that opens the door for the voices still haunting Lucy from her poor rural childhood, Strout talked about fiction as an opportunity to portray moments of grace. For all of us who struggle with the worthiness of imagined stories in today’s urgent world, that idea is both balm and guiding light.

Suvan Geer’s “Air”

Tupelo Hassman • Author of gods with a little g

In every writing space I’ve had, I’ve pinned a piece of notebook paper with the words of artist Suvan Geer. Geer’s work centers on the ephemeral, and when I was twenty-six, having just come out to myself as a writer, I attended the first ten-year survey of Geer’s installations, “Inaudible Whispers,” at the Huntington Beach Art Center, including, “Air,” a residual soot drawing of a hare strung up by its feet, ensnared. “Air” is a negative image, you see the hare’s shape only in the candle soot scattering from a body that has, somehow, escaped. Explaining the influence of a mentor is not unlike capturing a negative image, and coming to know a woman artist when I had just found that I was one left a blessed residue. Because of Geer and her work, I could begin to make out the shape of a life I wanted. Her words from the piece of paper that shine like a lamp onto my writing desk are, “Art without object.” In them, I find permission to take every day’s most important step, to begin. And, twenty years later, Suvan Geer has given me permission to have “Air” installed, permanently if you will, in the form of a tattoo on my right forearm. This way, when I am feeling defeated by the page, chin in hand, Geer’s hare will upend, find her feet, and in the dance for freedom, remind me that the most challenging traps to spring are the ones we set ourselves.

Yoko Tawada’s The Naked Eye

Laura van den Berg • Author of The Third Hotel

In my most powerful reading and viewing experiences, I felt like I was being consumed by the page or screen, that my own self was collapsing into that of the book or film, that I was outside of time. Yoko Tawada has been a very important writer for me and The Naked Eye (translated by Susan Bernofsky) is my favorite of her books. In that novel, the narrator travels to Germany for a youth conference, and is promptly kidnapped and held in captivity by a German man. In the aftermath, she travels to Paris and becomes obsessed with Catherine Deneuve films; eventually, the stories unfolding on the screen and the narrator’s inner reality collapse into one, so that the distinction between what is happening in “real life” and what is unfolding on the screen narrows. The corporal fades and the fictional takes over. Through these disruptions to reality, The Naked Eye ultimately poses a devastating question to the reader: What if the only way to exist in the aftermath of such an overwhelming physical and physic violation is to invent a way to live as though you have no body at all? Of course, Tawada has a large body of translated work beyond The Naked Eye. Last year, she was awarded the National Book Award for Translated Literature for The Emissary; New Directions has also published a number of her works in translation, including Memoirs of a Polar Bear and The Bridegroom Was a Dog. If you’re looking for new ways to see the world, I encourage you to find her.

Betty Edwards’s Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

Chia-Chia Lin • Author of The Unpassing

My sister and I spent half of our childhood in the small library near our house, and it must have been there that I came across Betty Edwards’s Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. The book was a bestseller when it came out in 1979 and soon after became an art class fixture, though these facts either were not apparent to me pre-internet, or were simply irrelevant to me at that age. What captured me then, and still does now, was not all the stuff about the lateralization of our brains, but the practical lessons on how to see an object if you wanted to draw the object as it truly was. There were exercises on reproducing an illustration by first turning it upside down before you copied it, or on breaking down a face entirely into the shapes of its shadows and highlights—steps that forced you to defamiliarize a thing, so you could no longer rely on your notions of what the thing was supposed to look like. When I’m having trouble with description in my writing, I often try to see things in this way (what does the negative space around the slouching character look like, what shapes are made when the sun hits the roof), in order to get past the shorthand and arrive at something closer to the truth. The book includes before-and-after drawings (before being taught to see by Betty Edwards, and after) that are so drastic as to be thrilling and also slightly unbelievable, though you want to believe them, and do.

Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work

Sarah Knott • Author of Mother Is a Verb

Our main literary heritage of motherhood veers between sentiment and judgement. In A Life’s Work, her memoir of early maternity, the novelist Rachel Cusk writes in a manner both stringent and apt. I read her on having my first child, passing the memoir around a circle of friends. I returned to her on wanting to write a wider history to such experiences. Now I read the Outline trilogy for a fierce example that we can make and remake genre as we go along.

The Brontës, Toni Morrison, Jean Rhys, and more

Rachel Eve Moulton • Author of Tinfoil Butterfly

In middle school, I began reading a weird mix of classics (think Tolstoy) and horror (Stephen King). Women writers in either category were few, even in the eighties. At least there were the Brontës. I fell in love with Jane Eyre. She reminded me of myself, nerdy and curious and underprepared for the world, but it was really Thornfield Hall and the idea of a haunted house that I adored. Later, in college, I read Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea and found a different haunted house to love. Then I read Beloved, a book I would also learn to love to teach. Women, I came to realize, are better suited to understand what horror literature does best—it manipulates reality to amplify the everyday terror women go through against the power of what it means to be female. What you understand to be true and real and right could easily be contorted until it is a shape you barely recognize, and in this way, the world can legitimately call you crazy. My own writing almost always comes from curiosity about this—as well as interest in the history of a particular place—a house, an island, a mountain range where the past is so rich with hurt that it can’t help but tangle itself with the present.

Jeans Rhys, Carolee Schneemann, Nina Simone, and more

Liska Jacobs • Author of The Worst Kind of Want

How do you pick just one? You collect them like wildflowers, choosing the ones that catch your eye, the ones that speak to you. Jean Rhys would be the first in my bouquet. Reading Good Morning, Midnight I felt seen. I was twenty and it centered me, made me feel there might be a place for me after all. Carolee Schneemann has been on my mind since her death earlier this month. Her performance Interior Scroll is a personal reminder of how to challenge androcentric expectations while finding strength in my own womanhood. Nina Simone’s Wild Is the Wind was the first time I wrote something to music that moved me. Diane Arbus, whose work could be a visual component to my own. Galka Scheyer and Marcia Tucker, trailblazers in a world that did not allow women to blaze trails. There are others: George Sand because I would have liked to be a badass in the nineteenth century, and Chopin’s lover. Mary Austin, Nella Larsen, Joan Didion, just to name a few. A kaleidoscope of women, inseparable only because together they make up the kind of woman I hope to be.

Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai

Lydia Kiesling • Author of The Golden State

I read The Last Samurai by Helen DeWitt when a galley of the New Directions reissue arrived, unsolicited, at my door a few years ago. I had heard the book was a cult favorite, didn’t know anything about it, and needed something new to read. I remember lying down on the couch during an afternoon when my baby was taking a longer-than-usual nap and being so surprised and intimidated and moved by what I read. Realizing that you could write a contemporary novel about a deeply intelligent, deeply peculiar woman, and include all kinds of challenging formal and stylistic elements, was hugely important as I thought about maybe one day writing my own novel. It’s a wonderful feeling, to be spoken to so clearly by a novel.

Martha Gellhorn

Lindsey Hilsum • Author of In Extremis

Martha Gellhorn was my heroine as a young journalist—and a role model for Marie Colvin, the subject of my biography In Extremis. She was what we wanted to be: a brave reporter, a passionate humanitarian, clever, funny, and glamorous. I loved her mischievous determination, stowing away on a nursing ship to get to France for D-Day after British commanders had banned female reporters. Her paragraph about watching a small boy struck by shrapnel in Madrid during the Spanish Civil War is a perfect example of the power of detail and observation. She was a much better journalist and writer than her one-time husband, Ernest Hemingway. Not that he, nor those who still admire him, recognize that.

Colette

Cathleen Schine • Author of The Grammarians

When I was a pretentious high-school student, I was very busy reading Heidegger and Robbe Grillet. My mother, in graduate school at the time, was reading Colette–not sure why Colette was assigned for a doctoral program in special ed, but volumes of Colette were strewn around the house (along with statistics textbooks). I skipped the statistics, but Colette was a revelation–sensuality without sentimentality; humor without cynicism; and beauty, an unapologetic love of beauty. I am still reading and re-reading Colette, still absorbing her intelligent openness to the physical world.

On her sister’s diaries

Samantha Hunt • Author of The Dark Dark

The diaries my sister Amy Hunt England kept when we were girls were a source of terrific inspiration. They were forbidden volumes to me as her younger sister so, watching her write them, felt like watching a secret be whispered. A secret I wanted to know. Our house was sometimes scary but in the diaries—yes, foul sister that I am, I read her private entries—she recorded a world of tremendous beauty, controlling our often out of control environment with her sharp eye for observing the world’s magnificence. She still does.

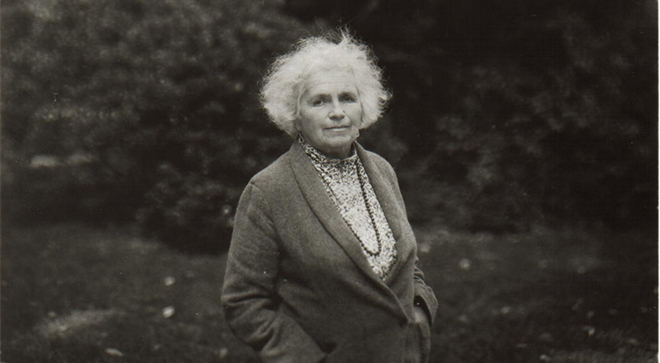

Grace Paley

Madeline ffitch • Author of Stay and Fight

I met Grace Paley when I was fourteen, working as a dishwasher at the Flight of the Mind women’s writing workshop in rural Oregon, where Grace was a teacher. Grace reminds readers that fiction must be alert to the “facts of money and blood,” and she embodied this. She’d burst into the kitchen during my shift and insist on doing a few loads of dishes. She’d come into the staff dormitory at night and read her stories aloud to us, the women who’d been keeping things running and keeping everyone fed all day. I listened to her stories, the extraordinary stuff of every day, the noise of neighbors and children and families, characters who were political actors not by stepping outside of themselves but by being themselves. I listened and I began to think I might try writing stories myself. Grace came into my life at a good time, when it was open season on teenage girls. The mass culture was doing it best to sell me lies about youth, beauty, body image, attraction, and desire. Yet there was no person I’d rather be than this very small and round old woman with wild white hair. I couldn’t imagine anyone more appealing or magnetic. Grace was incredibly serious about revolutionary practice, yet she incorporated this into her writing with compassion and playfulness, making room for human flaw and even absurdity. She reminds me that revolutionary work must be as imaginative as imaginative work. It is imaginative work.

Beth Nugent

Jac Jemc • Author of False Bingo

When I think of my development as a writer, many strong, influential women come to mind, but Beth Nugent is the writer and teacher who taught me the art of inquiry. At the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, she showed immediate support and enthusiasm for my work, which helped immensely to build my initial confidence. I was sure I was doing everything wrong, but I didn’t even know the questions to ask. She pushed me to interrogate my work and when I launched questions at her, she reframed every one and pointed them back in my direction. She asked why those were the questions I was asking and showed me a whole of new vocabulary of other questions to pose instead. She refocused the way I think about my writing, and for that, I can never thank her enough.

Ethel Johnston Phelps’s Tatterhood and Other Tales

Karen Olsson • Author of The Weil Conjectures

When I was a girl, my aunt gave me Tatterhood and Other Tales, a collection of folk tales in which the central characters are girls and women. Published in 1978 by The Feminist Press, Tatterhood doesn’t truck with Cinderella types—there’s not a passive heroine in the bunch. The stories, some of which I read over and over again, tell of a mother who dives into the belly of an elephant to save her children, or a young woman who rescues her beloved from his fairy kidnappers, or a grandmother, mother, and daughter who capture a famous wrestler and train him to become stronger, even if he’ll never be half as strong as they themselves are. I pored over this book, not so much because of how it tried to correct for our cultural surplus of submissive heroines (I liked Sleeping Beauty too) but because I preferred female-centered stories, and these ones were muscular and strange. So I’m indebted to the editor behind the collection, though I know almost nothing about her other than her name—Ethel Johnston Phelps—and the few facts in the capsule biography at the end of the book (a master’s degree in Medieval Literature, a native Long Islander, a community theater person). Her book expanded my sense of what women in stories can do.

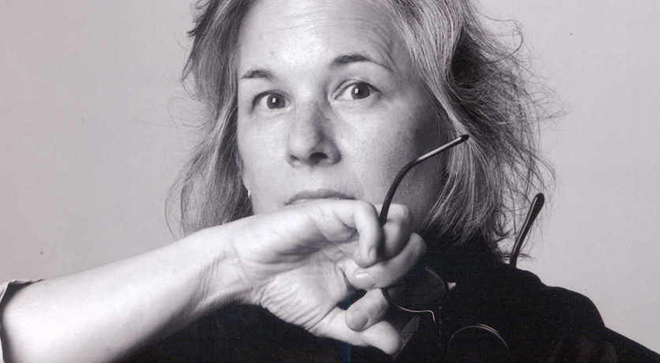

Diane Williams’s NOON

Kathryn Scanlan • Author of Aug 9—Fog

No one has influenced me more than Diane Williams. My first encounter with NOON—the incomparable journal she’s edited for the past twenty years—was like an electric shock. Williams is always the reader I have in mind when I write, and NOON is the extreme vertical challenge I’ve worked against for over a decade in attempting to make my art. She is a genius editor who has taught me—despite, or because of, frequent rejection and devastation—how to edit my work. As if that weren’t enough, her fiction—spanning three decades—is something I keep continually at hand, am continually learning from. In it can be found—how else to say it?—a sorcery which unlocks the power of language, frees it up, like fire, for the taking.

Leona Cottrell

Nina MacLaughlin • Author of Wake, Siren

Leona Cottrell: long thick cardigans over long blowsy dresses, all seasons; fuchsia lipstick on the straw of her bucket-sized iced coffee, all seasons; braless, all seasons; ageless—was she 37? 58? no knowing; present in her absence the way her heavy perfume—jasmine, orange peel, antiquity, smoke—lingered in the high school hallway long after she’d swept through on her way for a cigarette after teaching Latin or Roman Civ. Intolerant of bullshit, dismissive of what she called Judeo-Christian moralizing, Leona gave the sense that there was so much we know-it-all suburban teens did not, in fact, know, not in a bitter or condescending way, but in a way that alerted us to the thrilling scope of what awaited us as the world opened wider. And in her curiosity, her evident delight in bodily pleasure, she gave the powerful sense that the world could just plain go on widening. There is always so much to experience and know! She’s kindred with writer Annie Dillard in this way. Though Leona’s appreciations tilt more toward the carnal, wine and food and the muscled ravine of a chiseled male hip in a Hellenistic sculpture, where Dillard might pour her attention on a rodent, the two share a thrall with the world that transcends gender, a potent, curious hunger for being alive. What a good lesson to get so young, how to go on lovemaking to the world.

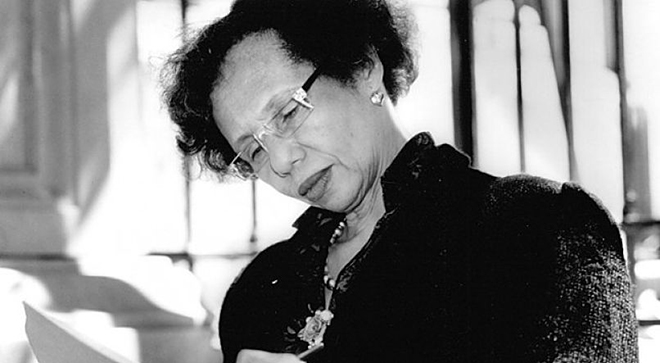

Simone de Beauvoir

Darcey Steinke • Author of Flash Count Diary

“The body,” Simone de Beauvoir wrote, “is the instrument of our hold on the world.” In The Second Sex Beauvoir interviewed women about their experiences from childhood, divorce, and old age, and then used philosophy to help the reader understand what it was to be a woman. Never sentimental or overly hopeful, Beauvoir’s work is meaningful because of its rawness. She inspired not with platitudes or fake redemption but by being honest about pain. After my own mother died, the first book I read was A Very Easy Death, Beauvoir’s book about her mother’s death. The book’s honesty about her mother’s harsh character helped me. “With regards to us, she often displayed a cruel unkindness . . .” and also the ability of life itself to console. “As we talked in the half-darkness I assuaged an old unhappiness.” In Beauvoir I found a mentor, who was willing to write the truth of the female body in all its many stages without embarrassment or shame.

Adrienne Kennedy

H. S. Cross • Author of Grievous

My last year of college, I got to take a playwriting seminar with Adrienne Kennedy. A petite, soft-spoken woman, she made it clear without quite saying so that our work together was of sovereign importance, so crucial that she could waste zero minutes on niceties, bureaucracy, or our anxious Harvard strivings for success. Our first assignment: Write about a landscape. How? How long? What format? She literally waved off our questions, shaking her hand and closing her eyes: Just write some pages. I had seen this exercise on the syllabus and was dying to write about England; now, having no instructions, I poured out my memories, conjuring the enchantment of those places that held me in their grip. The next class, she made us read out what we had written. No preambles permitted. Her critique was limited to nodding her head and murmuring “Yes” or “Very powerful” from time to time. She then announced we would begin writing our plays, right now at the table with our pens. What plays? How? Again, she waved us away, picked up her own pen, drew her own notebook close to her, and told us to begin. The class continued this way all semester. For the first time, I began to write wildly, without regard to how it would appear, or how appropriate or correct it was. I realized that I had been carrying around an internal critic—I saw him as a bearded creative writing teacher—but after only a short time with this strange, bird-like yet forceful woman, my lifelong urge to please was simply left to wither; our work was not about pleasing, there was no dramatic form we were meant to conform to, and because there was no pleasing or conforming, there was also no rebelling. There was only the landscape, the dream, the traumatic experience, the character, and the play that took shape week by week. Those months with her changed my writing more than any other single influence, freeing it from the good-girl prison of my youth and saying to the wild, living truth, “Yes. Very powerful. Yes.”