“David Means is a master of tense, distilled, quintessentially American prose…Each story by Means which I have read is unlike the others, unexpected and an unnerving delight.” —Joyce Carol Oates

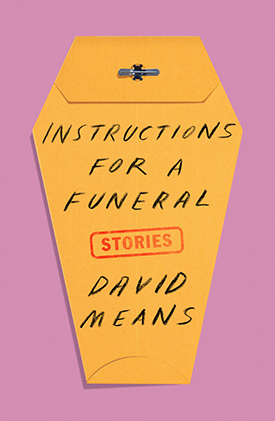

Following the publication of his widely acclaimed, Man Booker-nominated novel Hystopia, David Means now returns to his signature form: the short story. Thanks to his four previous story collections, Means has won himself an international reputation as one of the most innovative short fiction writers working today. Instructions for a Funeral finds Means displaying his sly humor and his inimitable way of telling tales that deliciously wind up to punch the reader in the heart. He transmutes a fistfight in Sacramento into a tender, life-long love story; two FBI agents on a stakeout in the 1920s into a tale of predator and prey, paternal urges, and loss; and a man’s funeral instructions into a chronicle of organized crime.

What follows is Means’s conversation with Educated author Tara Westover from an event at Books Are Magic.

Tara Westover: I’m a longtime fan of David Means. I discovered him while listening to the New Yorker fiction podcast—specifically the episode titled “The Treeline in Kansas.” I found it powerful for a number of reasons and it’s included in Instructions for a Funeral. I’m a huge fan of that story. It’s about a lawman who is reminiscing about something that happened in his life when he was younger. David, I thought we might talk, in the context of that story, about how stories work in your inner narrative.

David Means: That’s a tough question and it’s a profound question. Part of what I do when I write a story like “Treeline,” is to think of storytelling as almost like physics. I think of the physicality of the way we talk. We all tell each other stories and tell ourselves stories. Writing a story, however, is a completely different act. You’re able to eventually go back and control it and edit and restructure if necessary.

Westover: One of the things that struck me about that story is the way you deal with time. I found you were incredibly effective at being located in a specific moment. So much layering occurs, but it was so well done that I was never confused. I never felt in any way removed from the action. Things felt like they were happening now, but every once in a while I’d become aware that this all happened long ago; that these stories are being told by a narrator reflecting on events from the past. It makes you consider what it means that this is what this person is thinking about; that this is what he sits by the lake and ponders so many years later. It’s a convergence of different narratives: what’s happening now—it’s not actually happening now. It’s a story replaying in someone’s memory; a story that has stuck with them through many years.

Means: I figured out recently that every writer, no matter who they are, their personality somehow comes into the structure of what they’re writing. And I tend to be the type of person who always goes over a story again and again in my head: what if this had happened, what if I had not stopped at this stoplight. My anxiety and my personality as a human enters my fiction. So with the “Treeline,” I had these FBI agents on a stakeout. Originally I just wanted to write a cool stakeout story. And then while I was writing, I just naturally swam forward into the future. Maybe it was anxiety and not wanting to just stay there with the two men as they staked out this house.

I don’t believe in mystical things like “the character took over.” I don’t buy that. But I found myself swinging outwards in time to one of the older FBI agents. And while writing, I was thinking of my grandfather who was a hunter. He was a doctor, but also a hunter who wore bolo ties and was stoically quiet (my grandmother was not). My grandfather, who went deaf and decided he wouldn’t get a hearing aid. Maybe it’s just part of my personality to swing outwards in time in that way. And with that story, I took a lot of care in revising it.

Westover: Reading that story really taught me a lot about writing and about how to build a story because it’s so perfectly put together.

Hearing you describe your grandfather and hearing you say you were thinking about a specific person you knew from your life segues into my next question. I wanted to talk to you about the way Instructions for a Funeral is set up. It’s a collection of stories—fiction—but the beginning of it is this strange little essay about writing and storytelling in general containing quite a lot of autobiographical details. In that essay, you talk about hoping to be betrayed by the reader, which I think is a really interesting thought. Another thing that stood out to me is the sort of acceptance of the fact that things will fade; that things will be forgotten; that elements of the story will fade into oblivion, giving the whole endeavor a sense of urgency.

Means: I think when you’re writing or painting or creating any form of art, you’re trying to save yourself from time—not too get philosophical or anything, but you’re trying to make sure you stay alive somehow or that you win in the end. But then another side of you as a writer or an artist or creator of anything knows that you’re going to lose. Eventually a painting like Guernica by Picasso is going to fade—someday it’s going to go away. I think I was trying to explore, in that little introductory piece, the physics of that. My father died four years ago, so I think I was thinking about that too. But I wasn’t sure if I should put that at the beginning of the book.

I think when you’re writing or painting or creating any form of art, you’re trying to save yourself from time.

I meant that I hoped to be betrayed by the reader in a snarky, funny way. It’s good if the reader betrays you. You don’t really know what the reader is going to do with what you create. And part of the fun of writing is knowing that the reader is going to take it and make it their own. You instruct them on how to read you with just enough language so that it’s really their vision that they’re seeing. When you’re reading, it’s this miraculous thing. When I’m reading about Buck’s Peak in your book it’s my Buck’s Peak; I got to see the mountain. You gave me just enough to see it and I got to imagine it. That’s why when you go back and read a book you loved, Charlotte’s Web or whatever—it’s still your barn and everything that you imagined. You know that feeling? You’re re-remembering what you originally imagined. That’s what I was getting at in some ways.

Westover: I noticed in the “Treeline,” and other stories, there’s almost a verbal nervous tic that is in there, the “so to speak.” I love it. In a different writer’s hands it’d be incredibly annoying but the way you do it, it feels controlled and it does impose a kind of beat into it. I just wondered how you think of that, why you do it, and why isn’t it annoying?

Means: The “so to speaks” are mainly in that story and maybe a few others, and (in the original drafts) I put way too many, there were maybe thirty more, it was ridiculous—

Westover: So the reason it’s not annoying is because you’re an editor.

Means: Right, I edited. And in another story, “The Chair,” which is about parenting, and one parent in particular who’s remembering a time when he had to discipline his kid and make a decision about how much to say, “Ok you’re going to have a time-out.” I hate that phrase “time-out.” Then the phrase, “I think I thought” entered the story. There were a ton of “I think I thought’s.” “I think I thought I think” was another one. So, I edited a bunch out—it was just a way of changing the voice of the story a bit. But it might be a verbal tic, too.

Westover: I found it had a beat almost like music, it kept coming back. In that same beginning of the book you make a point about violence. In effect you say, if you’re writing a whole story about violence you’re doing it wrong.

Means: You should know what violence is if you’re going to write about violence. You should understand what it really is. Not gratuitously create scenes of violence just because they’re titillating or fun. You should have some kind of knowledge of what violence really is.

Westover: In the “Treeline” which I love so much, one of the things I learned from that story is that there is a violent thing that happens in that story, but it’s actually the quietest part of that story. It’s almost completely peaceful—the violence happens kind of off-stage. There’s a lot happening in that story; a lot of noise. Then there’s this total silence in the part that actually contains violence. There are so many things I learned from that story and that was absolutely one of them. It’s said that if you really want people to listen to you, you don’t raise your voice—you lower it.” And I had never thought about how that would work in a narrative and what it means to lower your voice in a narrative for the most dramatic part. And that story absolutely does that.

Means: When I was writing my novel I was researching PTSD and talking to a lot of Vietnam vets and WWII vets and I’ve had my own traumatic experiences as a kid. And I’ve come to discover that there is a kind of silence around moments of violence. I struggled a lot deciding if I was going to put this sequence of things at the beginning of the collection. It’s a sort of mini-lecture. But more of a mini-lecture to myself about what I’m doing as a writer.

Westover: I’m very glad you put it in there, but I want to push you on that. Why this defense of storytelling? Or this interrogation of storytelling? And why these few autobiographical bits? This description of your dad and his death is incredibly short, very powerful, but very short. I’m so glad it’s there but I also wondered, why is it there?

The way I think of a story collection is sort of like a record album where each story resonates off of the other stories and forms a sequence.

Means: The way I think of a story collection is sort of like a record album where each story resonates off of the other stories and forms a sequence. So, the reader will read this outpouring of what seems like autobiographical material, although it’s not, really, and then they’ll move into a story that’s completely imagined. In other words, the second story in the book is about a fistfight in Sacramento. It’s actually based on a friend of mine. I was just out in Reno giving a talk about his work. He grew up on a ranch and became a writer and now he’s in his late 70s. He was telling me about fighting in California. And it goes from being a fistfight story to a love story. You’ll have to read it to figure out how that happens. I wanted that opening sequence to make the reader think about creativity and the imagination and the issues at hand and then go into a story that was completely imagined. And this has to do with auto-fiction too. All the interesting novels that are being written, like Jenny Offil’s Dept. of Speculation—I just met her and found out that even though it sounds like you’re reading an autobiography most of it wasn’t true. So, I was thinking a lot about the imagination and the power of it and our ability to imagine out of nothing. I’m a little worried—and Calvino was a writer who was worried about this too—that we’re going to actually lose that ability to just imagine things whole cloth from nothing.

Westover: Why would we lose it?

Means: Well . . . where’s my phone? Because of our phones. Because we’re being fed pre-fabricated images all the time. We don’t have the room to just daydream the way we used to and it comes out of daydreaming. Also, there’s this sense that we don’t respect the imagination the way we used to. One of my theories is that auto-fiction is more digestible because it feels like you’re just reading an autobiography of somebody. The idea that the writer just imagined something completely out of nothing—you don’t have to deal with that in certain kinds of narrative.

Westover: I’m thinking about how a lot of memoirs have pictures in them. I was kind of controversial in saying I didn’t want any pictures in my book. But the reason I didn’t want pictures was that I feel like when you read a book you, the reader, supply that image, like you said. For anybody who reads the book, my dad is actually their dad or their mom. I wanted that to actually take place. It didn’t matter if I described him looking a certain way. They’re going to supply the most appropriate image for their lives. I remember when I read the Harry Potter books as a teenager then got saw the movies when I was older. That whole world which I’d made in my mind—I lost it. And now when I think of Harry Potter I do think of Daniel Radcliffe. That’s just how it is. And it was something I didn’t want to have happen with my book. So, no pictures.

Means: And you open with Buck’s Peak and the image of the mountain that gives the reader a lot of room into the story. And in the scrap yard scenes, you leave a lot of room for the reader to come in with imagining. And you wrote those scenes in a fictive way so that they could see.

Westover: I feel too that no matter how much you give people—you can tell them this person was short and had brown hair—if their own experience is someone tall with blonde hair, that’s what they’re going to see. As soon as you actually supply the image, I think, it becomes a lot harder for people to build with their own imagination.

Means: Especially if you move the character. Movement is really important in fiction. It doesn’t take a lot of instructions to get the reader to see something. If I say, “Janet went to the sink, picked up the roll of paper towels, and went back to the table,” it’s your kitchen, you imagine. I just said those words. A little goes a long way; you don’t have to do much to make the reader see.

Westover: How do you find that balance personally? When do you feel you’re over-describing this? When do you feel you’re not giving enough?

Means: Editing. Cutting.

Westover: But your sentences must be incredibly hard to edit. I mean just looking at that, I think that might’ve actually been one sentence. It would be incredibly difficult to edit because it’s so rhythmic, you use that style where you have a strong idea and then you attach phrases to it. And that must be very difficult to alter.

Means: I’ll rewrite a sentence again and again and work it over and pare it down. I never intend to write long sentences. Sometimes I do it at the beginning of a story to make sure the reader at least reads the first sentence. They’ve got to get through that.

Westover: I like it. I think they’re clear, they’re easy to read but they are often very long and complicated. But I think we’re leading a whole generation of writers astray by effectively teaching them how to write microwave manuals.

Means: I’ve been noticing on Goodreads some of the reviews have been something like, “I didn’t finish this book because there were lots of long sentences.” And one said there were too many run-on sentences. But I don’t believe there’s one run-on sentence in the book?

Westover: They’re not hard to follow, that’s the thing. A long sentence that’s hard to follow, that’s a problem. But it’s a problem because it’s hard to follow. I mean a short sentence can be hard to follow.

Means: And in the “Ice Committee,” a story that’s close to my heart for a lot of reasons, I intentionally wrote a lot of short sentences. Not overly planning it but the rhythm just wanted short sentences.

That weird advice we give to people, “vary your sentence lengths but keep them all short,” I just think it’s wrong.

Westover: And you’re able to get that rhythm in there. I think you can’t have real rhythm without having some flexibility with the length of your sentences. You have to be able to add and subtract and have a short phrase and a long phrase. That weird advice we give to people, “vary your sentence lengths but keep them all short,” I just think it’s wrong. It’s a cult of Strunk and White that I actually think is just wrong. I think it’s incorrect but very good for writing microwave manuals!

Means: There’s a story by Chekhov that starts with the word “night.” The first sentence is night, period. That’s it. When I teach I tell my students, the rules that you hear from your teachers are sometimes ridiculous. “There can’t be a one word sentence”—yes there can! I mean little short sentences are wonderful, really, seriously. I love fiction that has short sentences. But sometimes you want to get in there with a long sentence.

Westover: Possibly one that’s a page.

David Means was born and raised in Michigan. His Assorted Fire Events earned the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for fiction and The Secret Goldfish was short-listed for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Prize. The Spot was selected as a 2010 Notable Book by The New York Times and won the O. Henry Prize. His first novel, Hystopia, was published in 2016 to wide acclaim and was long-listed for the Man Booker Prize. Means’s fiction has appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s Magazine, Esquire, The Best American Short Stories, The O. Henry Prize Stories, and numerous other publications. He lives in Nyack, New York, and teaches at Vassar College.

Tara Westover is an American author. Born in Idaho to a father opposed to public education, she never attended school. She spent her days working in her father’s junkyard or stewing herbs for her mother, a self-taught herbalist and midwife. She was seventeen the first time she set foot in a classroom. After that first encounter with education, she pursued learning for a decade, graduating magna cum laude from Brigham Young University in 2008 and subsequently winning a Gates Cambridge Scholarship. She earned an MPhil from Trinity College, Cambridge in 2009, and in 2010 was a visiting fellow at Harvard University. She returned to Cambridge, where she was awarded a PhD in history in 2014. Educated is her first book.