When Aatish Taseer first came to Benares, the spiritual capital of Hinduism, he was eighteen, the Westernized child of an Indian journalist and a Pakistani politician, raised among the intellectual and cultural elite of New Delhi. Nearly two decades later, Taseer leaves his life in Manhattan to go in search of the Brahmins, wanting to understand his own estrangement from India through their ties to tradition. Known as the twice-born—first into the flesh, and again when initiated into their vocation—the Brahmins are a caste devoted to sacred learning. But what Taseer finds in Benares is a window into an India as internally fractured as his own continent-bridging identity. At every turn, the seductive, homogenizing force of modernity collides with the insistent presence of the past. In a globalized world, to be modern is to renounce India—and yet the tide of nationalism is rising. Taseer struggles to reconcile faith in tradition with hope for the future and the brutalities of the caste system, all the while challenging his own myths about himself.

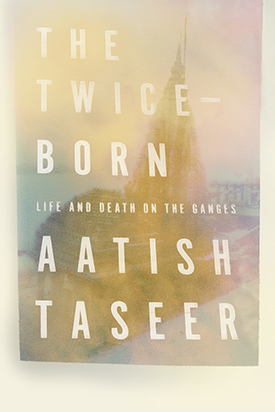

What follows is Taseer’s conversation with Karan Mahajan (author of The Association of Small Bombs) from the launch event for Taseer’s new book, The Twice-Born, at Books are Magic.

Karan Mahajan: I wanted to begin with the question of why you chose Benares as a microcosm to study the spiritual and intellectual ideology behind what people call Hindu nationalism. Why not go all over India seeking Brahmins, for example?

Aatish Taseer: I was worried about that kind of surveying trip—the writer goes one place, he goes another place, he goes on and on. And I had this experience of the city. I was on my way to university in America and my mother very emphatically—it had suddenly come to her, this idea that, oh no, you must go to Benares. It had never really arisen between us before. We were very blissfully deracinated, and then I was going onto another stage, of a deeper deracination. Suddenly this place came up, a note of panic in her voice, and she said, I want you to go to this place. The city entered my life in that way, as an eighteen-year-old, and after that, I was haunted by its significance. It kept returning. I’m not a religious person, so I was trying to decipher it by my own lights. And then something weird happened, because I’d gone in 2014, just to see if this was something I could write about. At that very moment, as I was doing this reconnaissance trip, news spread like a rumor in the Old City that Modi had chosen the city as his constituency. He wasn’t from there, but he was obviously trying to repurpose its religious power for his politics of revival, and I thought, this is right. It is the ultimate metaphor for India. It’s where all of India collects, it’s meant to be a place where all the holy sites of India are reflected, and Benares, in turn, is reflected all over India. It’s a way of stitching together this very disparate, varied country. I thought I would use that symbolism for my own purposes.

Mahajan: One mark of your integrity as a writer in this book is that you stay very close to the spiritual lives of the characters that you’re interviewing. It surprised me that there were fewer bulletins about Modi, especially since you were reporting for a magazine when Narendra Modi was elected with what would become the biggest mandate an Indian politician and his party had received in thirty years. So I’m interested in the decision to elide some of that material, to not put all of it in.

One mark of your integrity as a writer in this book is that you stay very close to the spiritual lives of the characters that you’re interviewing.

Taseer: You mean to keep out some of the political stuff? I suppose that I would always have been interested in the cultural phenomena that were creating the politics, just as if we were here, I would be less interested in the process of election, but rather in the cultural fault line that had brought about this new figure. I think that would’ve been part of it. Also, we now talk about the fact that we have this sort of pantheon of characters who’ve all been thrown up, from Eastern Europe to the United States to places like the Philippines and Brazil. Modi was the first, and there was no real language to discuss what had happened. But of course, you and I know that, living in India, if people were to tell you about the isolation of an elite and a heartland in revolt, one would’ve known that this would have been the first laboratory for that sort of thing to come to the front.

Mahajan: Did you feel that the election, which was a sort of earth-shattering event, became a fault line within the book as well? That there was a period of reporting before, and then after, or that more of the material from after the election was making it into the book? I’m curious about how you managed that transition, because, again, the flavor and the mood of the place did change overnight with Modi’s election.

Taseer: I had a very strange reaction to that election, and it’s very embarrassing for me in some ways. As a journalist and commentator, in that capacity, I thought it would be a good thing. And then, in my heart, as somebody of Muslim background, of an English-speaking family, all of those things, I knew in my heart of hearts that it would mean my leaving India for good, that a world would come into being where there would be no room for somebody like me. I think that all of this was working much more under the surface. I remember one of the images that struck me, that left me with the impression of the opaque character of that election, is that his supporters would wear these Modi masks. These young, restless men would walk the streets with these cut-out masks of him. It was sinister and it left an impression, but there was also a real feeling that something had been veiled, and that a kind of chauvinism had been converted into a desire for development and prosperity. And yet one knew that it was a kind of gamble, and that if the prosperity was to go bad, that the other thing would come to the front. The impression was really that feeling that I couldn’t see very well in 2014. I had my conversations, but the landscape was simply too opaque to form a clear judgment about it.

Mahajan: I would guess that another reason for Benares’s opacity for a writer is the sediment of cliché that has settled over it, over the years. It’s a place that foreign writers have often gone to for their little exotic jaunt in India. As someone from India, what were you conscious of not doing? How were you trying to chip away that sediment?

Taseer: There’s a line in the book where I talk about traveling with a white man on my shoulder, having this double experience of experiencing the place as myself, and then experiencing it on behalf of this other self. And I have my heart in my mouth, because Benares has this grotesque quality—

Mahajan: Can you describe it for people who’ve not been there?

Taseer: It’s a very striking image of a city. The Ganges bends towards the north, and this bend is considered very auspicious, because here’s a river that’s flowing all the breadth of India, and suddenly it curls around, and starts to flow towards its homeland, its source, in the high Himalayas. That bend is what the city is built around. Unlike many Western cities built on a river, there are not two sides. It’s a city that looks into an abyss, a nullity. That empty other bank is the enshrinement of this Hindu idea of the abyss. It’s not simply that no one made a bridge or that no one decided to live on the other side—it’s actually kept that way. On a very basic level, when you first see it, it goes through you as that enduring image of Indian philosophy and thought realized in the form of a city. There are a few cities that have that feeling, where you see them and you think, wow, this is not just a city, but it’s actually the realization of the spirit of a culture. Benares very much feels like that.

There are a few cities that have that feeling, where you see them and you think, wow, this is not just a city, but it’s actually the realization of the spirit of a culture.

It also has this quality, they use this word tamas, which is related to the English word tenebrous, to do with an underlying darkness. That’s because it’s presided over by Shiva, who is the god of creative destruction, and he has this chthonic energy or quality. People are very quickly ill at ease in that city. You’ll find someone arriving and really finding themselves nervous, and it’s not something that’s in their head. The people of Benares will tell you it’s very real, it’s palpable, it’s part of the spirit of the place. It’s one of those cities—a little bit like Venice—where it can kind of turn on you. The darkest side of the place is something that’s not in your head, but that’s very much part of the character of the city, so much so that they have a special deity who you propitiate, called Bhairava, a very fierce form of Shiva, before you come into the city, in case it treats you roughly.

Mahajan: I wanted to touch upon something you brought up in the excerpt you read. Which is this awareness you have, which I think is quite unique, of the distance between you as a person and what you perceive as Indian “tradition” or “culture.” This is a situation of course that most English-speaking elites in India are in. But the way it manifests usually is as a kind of defensiveness and an authenticity mania—people pretending that they are much more “authentic” than they are. How did you get to the point of being so honest about your alienation from the place that you grew up in?

Taseer: I think the relationship with Naipaul does matter in this respect. If there was any lesson that came to me from him, it was that total horror of falsity and of lying. And one was surrounded by it in India. People were always trying to elide; that kind of person who was performing at being full of ethnic knowledge and pretending that they weren’t colonizers and knew everything about India—throwing in a few words of Hindi and sipping their white wine. This was obviously something that was troubling. In those days it seemed to be a preoccupation only of the elite.

In my last book, I had a character who was a professional Indian. And I thought very much that I didn’t want to end up like that. I was like, I’m going to recognize whatever I am. And also recognize the fact that this was not incidental. It was not just me who got picked out to go off. I was part of an actual historical experience. And one could not confront that experience by pretending it didn’t happen. And it didn’t take long before the realization that there was another side who was not so happy to be talked down to by this little world. And that very quickly it was able to express its might politically, and so it has. So the thing that I was trying to be honest about—well I didn’t really have to be honest about it very long because quickly it would have come to the front anyway.

Mahajan: I don’t think you’re giving yourself enough credit. There are plenty of people in the Anglicized elite who are still in a state of extreme confusion about what’s happening.

In your book you also talk about the difficulty of finding a shared vocabulary with people who speak in religious abstractions—who belong to a world that is so fully formed that they can’t see it as a world. How did you go about bridging that distance? How did you interview them? How did you get them to open up?

Taseer: You can’t really. The people that are the most interesting characters in the book are really in some ways people who have broken from that purely instinctive world of tradition. There’s a moment with one of the characters at the end of the book where we’re dealing with somebody who, people tell me he lives as Brahmins have lived for a thousand years, maybe 1500 years, and he teaches this one branch of ancient learning. He’s so isolated that even a word like “modernity” has no meaning for him. He doesn’t know that he’s been encircled by this other thing. And so finally he says we’re living in a time of kalyug, which is the last of the great Hindu stages. It’s the age of vice and of dissolution and it presages a period when the cycle will come to an end. And I use kalyug as a substitute for modernity. And suddenly his face lights up because a common word has been found. But otherwise it isn’t really possible to reach that deep world of vision. It’s something to be observed.

Mahajan: Did being a student of Sanskrit help as a way in? Is that one of the reasons you were drawn to the Brahmins in the first place? Or did the interest in the Brahmins come before the interest in the Sanskrit?

Taseer: It helped that I had a beginning point in that way. But I was fascinated by what I saw as an aristocracy of the mind that had existed in India for all of these years. Brahmins were grammarians. They were scientists. They were this caste that had been set out to do the work of the mind. And they had twenty or thirty centuries of literary production. It just seemed like such a fascinating prism to use that reduction and scale to get at something bigger. Because it would be so much to try and deal with the question of tradition and modernity over a place like India. But I thought, if one could go very small, then one could see this thing in this limited way.

Mahajan: And there’s a point in the book where you have a very personal interaction with the force of caste in a way that you hadn’t had before.

Taseer: Caste is our deepest level of identity. We can compare it with race in this country or with class in England. It’s also something that has been given a metaphysical foundation. There have been systems of inequality in the past but probably no system has a deeper foundation than caste. And I realized this is a moment when something that I’d conceptualized suddenly acquired a very simple, very concrete reality.

There have been systems of inequality in the past but probably no system has a deeper foundation than caste.

Mahajan: What were the most interesting defenses of caste that you came across? Because this is a book about the revival and preservation of caste, as well.

Taseer: That chapter with Mukhopadhyay—he’s a Brahmin from Bengal—and he’s by far the most eloquent and he comes out of that whole tradition of the Bengal renaissance, where for one moment, there’s this fertile relationship between Britain and India and a flowering at the line of contact between these two cultures. And this man is the product of that. He’s very rigid and conservative. He says that he’s re-thought all the aspects of tradition, but that he’s ready to make a formal defense of it. We have this moment where he says, Well, in the West, you have this idea that all men are created equal and they become differentiated. With us, we have the idea that you are fundamentally born unequal. But we’re all—Brahmins, Sage, Untouchable—all headed to the same destiny but obviously over many lifetimes. And I remember first hearing this explanation and thinking this was interesting. And after doing the trip to the village where I encountered casteism in practice, after having this experience which I describe in the book, I started to corner him and limit him to this question of the actual food prohibitions. And he was made uncomfortable by it. He doesn’t like to be cornered on this small thing. He keeps saying there’s nothing wrong with it. And finally he says to me, Well, you in the West. You have this idea of contamination when somebody is sick. You wouldn’t let them near you, you wouldn’t let them touch your plates. But you will not admit our idea of spiritual uncleanliness. And it’s a horrible moment because it’s one of those instances where a human contact is established between two people who are very different, and we’ve been able to talk extensively and then suddenly something appears where you’re completely riven from this person. You’ve confronted an actual belief that is quite separate from the personality of the person that makes it just impossible to go further. And he seems to realize that too.

Mahajan: And in a way he echoes a sentiment that many of the characters in the book bring up. Shivam says at one point: “Either we throw ourselves into this modernity, or we go back to what we were. What is intolerable is this limbo, this middle condition.” Now this is very much at the heart of Hindu nationalism and revivalism, but you did bring up this interesting contention about the Bengal renaissance, which was a period when India and Britain actually had a kind of fruitful cultural contact. Is there any way that the limbo period could be more productive? Is there an alternative history in which one wouldn’t be panicking in one direction or the other, towards extreme modernity, which is all science, or extreme tradition, which is someone saying, accept spiritual contamination?

Taseer: What I’ve discovered subsequently is that that feeling of being acted upon; of people living in a place who are quite rooted (like Shivam) and who feel that they are living in a world that has grown strange—that a kind of homelessness has come to them, even to people who have never left home. That experience is something that—and I didn’t know it at the time—is much more universal than we realize. I think that people in Britain feel that. I think people in this country have felt that. And the ability for it to be used politically is now something that people are able to see across that line. I don’t know if we’re dealing anymore with the situation of one country trying to deal with this phenomenon but rather something that’s now kind of abroad in the world. I had always expected to use the book as a metaphor and to use Benares as a metaphor and the Brahmins as a metaphor. I hadn’t thought that this thing that happened to me in 2014 in India would follow me to England and to America. I was full of misgivings that the subject of this book was too far away, because we were in the happy days of Obama, and it just seemed very remote. And my editor here, Eric Chinski, I remember him saying a few months into that moment with Trump, “Well, now you know that this theme has broken the bounds of that place.” So I think that the Indian situation is particular because that tension between the elite and the heartland and revolt is also founded in a history of foreign rule and foreign occupation, but the actual lines now are too universal to be put down to the experience of one country.

Mahajan: Related to this, you bring up in the book how the acceptance of the death of a culture can be an important stage for a renaissance movement. The Renaissance in the West happened when one accepted that the classical world was coming to an end. Did you see any signs of that at all or were you only exposed to the opposite feeling when you were in India?

Taseer: I saw many signs of the actual thing dying. There’s a moment in the book where I say, here’s this culture that has confronted the fact of death probably better than any other culture or philosophical scheme I know. The idea of death, so terrifying in the West, the sting is completely taken out of it in a place like Benares, and death is kept so near. But that the same culture has not been able to accept that the culture itself is dying—seeing that erosion is very real. I didn’t feel that that moment had come, people were still talking about rescuing and repeating the past. They were not ready to let it go. And I think that that moment when you walk away from the past and when you’re not trying to still firm up the world of tradition—that you’re willing to admit that this thing has died—I don’t know if people in India can see that yet. The pain is too much for them to see that that loss could actually be creative.

Aatish Taseer was born in 1980. He is the author of the memoir Stranger to History: A Son’s Journey Through Islamic Lands and the acclaimed novels: The Way Things Were, a finalist for the 2016 Jan Michalski Prize; The Temple-Goers, which was short-listed for the Costa First Novel Award; and Noon. His work has been translated into more than a dozen languages. He is a contributing writer for The International New York Times and lives in New Delhi and New York.

Karan Mahajan grew up in New Delhi, India and moved to the US for college. His first novel, Family Planning (2008), was a finalist for the International Dylan Thomas Prize. His second novel, The Association of Small Bombs (2016), was a finalist for the 2016 National Book Awards and was named one of the “10 Best Books of 2016” by The New York Times. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The New Yorker Online, The New Republic and more. From 2018-2019 he will be a fellow at the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library.