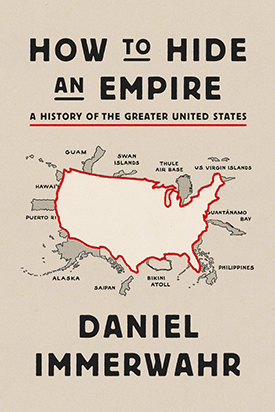

In How to Hide an Empire, Daniel Immerwahr tells the story of the United States outside the United States. He reveals forgotten episodes that cast American history in a new light and offers an original conception of what empire and globalization mean today. In the years after WWII, Immerwahr notes, the U.S. moved away from colonialism. Instead, it put innovations in electronics, transportation, and culture to use, devising a new sort of influence that did not require the control of colonies. In the following excerpt, he talks about U.S. foreign bases after WWII and specifically how the base city Liverpool became a cultural hub that helped spawn the Beatles.

In 1949, George Orwell conjured up a dark future for Britain. Atomic warfare had ravaged the industrial world. A dictator had taken command. Seeking to “narrow the range of thought,” the government was gradually replacing the English language with a nightmare version of Basic, called Newspeak. And Britain had been absorbed into the United States. Its name had even been changed, from Britain to “Airstrip One.”

Orwell’s novel 1984 was mainly a warning about totalitarianism. But in imagining Britain as a forward base for a U.S.-centered empire, Orwell noted another important trend. The Second World War had seen millions of U.S. servicemen touch foot on British soil. In theory, their presence had been temporary. But as the “cold war” (a term of Orwell’s coinage) began, it became clear that the United States would be staying for some time.

During World War II one of the most important British bases for the United States had been Burtonwood, which hosted more than eighteen thousand personnel at peak. In 1948, the year before Orwell published 1984, the U.S. Air Force returned there. Burtonwood was repurposed to support the Berlin Airlift. It became the largest air force base in all Europe. Thousands of servicemen stayed there, and they didn’t leave until the 1990s.

This was an important feature of the United States’ pointillist empire. Some of its “points” were on islands or remote spots, such as Thule, the Bikini Atoll, or the Swan Islands. But others were in heavily populated areas. Troops spilled out from the bases, drinking, frequenting clubs, trading on the black market, and organizing trysts. And people who lived nearby found work on the bases or selling to servicemen. The bases and their environs, in other words, were bustling borderlands where people from the United States came into frequent contact with foreigners.

The bases and their environs, in other words, were bustling borderlands where people from the United States came into frequent contact with foreigners.

The bases were there by agreement—Washington offered protection and usually funds in exchange for the right to plant its outposts. But for the people who lived next to them, it could feel like colonialism. French leftists complained of U.S. “occupiers” and grumbled about “coca-colonization.” In base-riddled postwar Panama, thousands marched carrying signs reading DOWN WITH YANKEE IMPERIALISM and NOT ONE MORE INCH OF PANAMANIAN TERRITORY.

For the British, the main issue was the nuclear weapons. The United States had been storing its weapons at British bases, and it flew B-47s over England. Were they carrying nuclear bombs? “Well, we did not build these bombers to carry crushed rose petals,” the U.S. general in charge told the press in 1958. He was bluffing, slightly—those bombs were unarmed. But the terrified British public had no way of knowing that.

Within months, more than five thousand well-dressed protestors gathered in the rain at Trafalgar Square. From there, they marched for four days to a nuclear weapons facility in Aldermaston. By the time they reached it, the crowd had grown to around ten thousand.

These numbers weren’t enormous. But that people had turned out at all, in the 1950s, in the heart of NATO country, to protest the logic of the Cold War was impressive. NUCLEAR DISARMAMENT and NO MISSILE BASES HERE, their banners read in sober black and white.

An artist named Gerald Holtom designed a symbol for the Aldermaston march. “I was in despair,” he remembered. He sketched himself “with hands palm out stretched outwards and downwards in the manner of Goya’s peasant before the firing squad. I formalized the drawing into a line and put a circle around it.”

The lone individual standing helpless in the face of world-annihilating military might—it was “such a puny thing,” thought Holtom. But his creation, the peace symbol, resonated and quickly traveled the world.

• • •

In Holtom’s eyes, the bases sowed fear. Yet seen in another light, they had a certain glamour. The men posted to them were flush with money and consumer goods. So even as the bases provoked protests, they also stirred other passions.

Take Liverpool, a port city in the north of England. Before the war, it had been a dreary factory town without much by way of entertainment beyond the music-hall scene that typified much of provincial England. Then suddenly, in the 1950s, it lit up like a Christmas tree. It turned out far more chart-topping acts in the following decades than it had any right to. Some, like the Searchers or Gerry and the Pacemakers, have faded with time. Others, like the Beatles, have not.

A classmate of John Lennon’s estimated that between 1958 and 1964, five hundred bands were playing Merseyside, the area around Liverpool.

Why? “There has to be some reason,” wrote the Beatles’ producer George Martin, “that Liverpool, of all British cities, actually had a vibrant teenage culture centred around pop music in the 1950s, when the rest of Britain was snoozing gently away in the pullovered arms of croon.” That Liverpool had a port surely helped. Yet for Martin, the answer was to be found elsewhere. Liverpool was a base city. It was, in fact, fifteen miles west of Burtonwood, the largest U.S. Air Force base in Europe.

Burtonwood was, it must be emphasized, enormous. It was the “Gateway to Europe,” where transatlantic military flights landed. Its 1,636 buildings included the largest warehouse in Europe and the military’s only European electronics calibration laboratory, which technicians used to set their instruments and test standards. It had a baseball team, a soccer team, a radio station, and a constant influx of entertainers from the United States (Bob Hope, Nat King Cole, Bing Crosby).

Burtonwood’s significance would be hard to overstate. Whole neighborhoods of Liverpool had been bombed during the war, especially around the Penny Lane area, and its economy was still in shambles. The thousands of U.S. servicemen who came through were like millionaires. Teenage girls charged at them at the train station (The Daily Mirror, suspecting prostitution, judged this “shoddy, shameful, and shocking”).

Whole neighborhoods of Liverpool had been bombed during the war, especially around the Penny Lane area, and its economy was still in shambles. The thousands of U.S. servicemen who came through were like millionaires.

In its official contracts alone, Burtonwood plowed more than $75,000 into the local economy per day. And that doesn’t count the money for entertainment. Musicians did especially well. They could get gigs on the base, or they could catch the troops who, pockets bulging with dollars, made their way to the Merseyside clubs at night.

In George Martin’s eyes, this was transformative. The troops, he recalled, “brought their culture—and their favourite records—plugging both directly into the mainstream of Liverpool life.” The men dispensed nylon stockings, chocolate, money, and records like an army of boisterous nocturnal Santa Clauses. The base became “an absolute magnet for any woman between the ages of fifteen and thirty.”

Young men got caught in its magnetic field, too—John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr especially. Ringo’s stepfather worked on the base and fed Ringo a steady diet of comic books and records from the United States. John’s mother, Julia, was known as a “goodtime girl,” an avocation that, whatever else it entailed, left her with an admirably large and up-to-date record collection, which John and Paul eagerly raided. George got his records by stealing them from Brian Epstein’s shop, which, thanks to the troops, was brimming with the latest music from across the Atlantic (Epstein later became the Beatles’ manager).

At a time when Britain’s cultural institutions were locked in the vaudeville age and the BBC was trying to stamp out rock, Liverpudlians found themselves in a special position. They had records, particularly those featuring African American artists, that no one else had access to. And they strong financial incentives to master the songs emanating from the United States.

Their music scene exploded. Tellingly, the Liverpool groups were essentially cover bands. They one-upped one another not by composing new songs, but by replicating faithfully the sounds they heard on records and the radio.

The first side that John, Paul, and George recorded was “That’ll Be the Day,” a Buddy Holly number performed with remarkable fidelity to the original. They weren’t trying to dislodge Holly, just to establish themselves as recording artists in his style. There was only one copy pressed, which the bandmates passed around—today it’s the most valuable record in existence.

They cut it in 1958, the same year the antinuclear marchers moved on Aldermaston. The Beatles and the peace symbol, in other words, debuted within four months and a day’s train ride of each other. And both were side effects of the U.S. basing system.

The Beatles and the peace symbol, in other words, debuted within four months and a day’s train ride of each other. And both were side effects of the U.S. basing system.

• • •

Eventually the Beatles themselves would join the movement that began with the march on Aldermaston. Paul McCartney appeared on television in 1964 calling for a ban on nuclear weapons. Three years later, John Lennon offered his own protest of the United States’ basing system. “Look what they do here,” he complained. “They’re spending billions on nuclear armaments and the place is full of U.S. bases that no one knows about.”

Such opinions may sound strange coming from a band that owed its very existence to the U.S. military, but that’s often how it went. Those who lived in the shadow of the bases both resented them and built their lives around them, vacillating between protest and participation.

Daniel Immerwahr is an associate professor of history at Northwestern University and the author of Thinking Small: The United States and the Lure of Community Development, which won the Organization of American Historians’ Merle Curti Award. He has written for Slate, n+1, Dissent, and other publications.