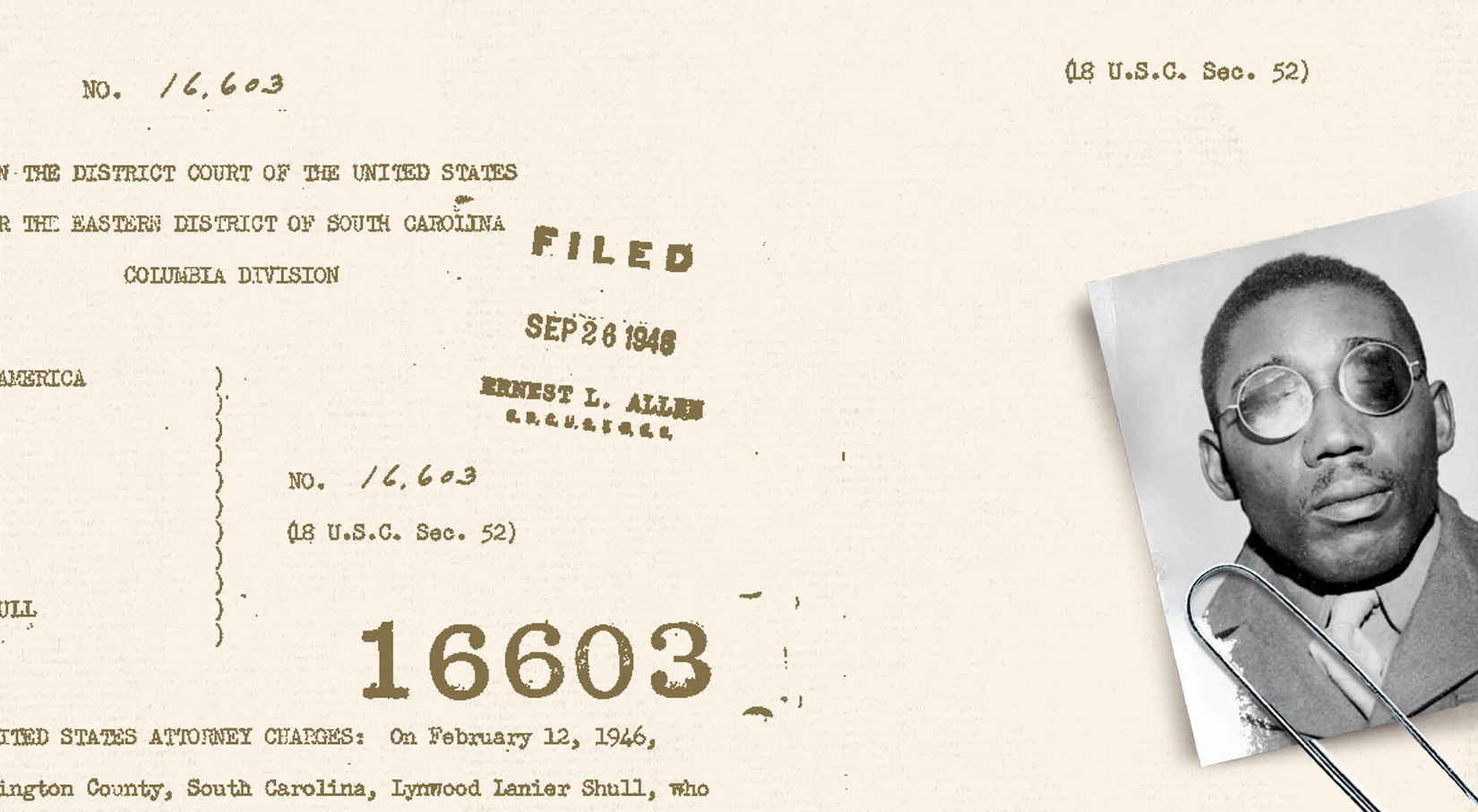

On February 12, 1946, Sergeant Isaac Woodard, a returning, decorated African-American veteran, was removed from a Greyhound bus in Batesburg, South Carolina, after he challenged the bus driver’s disrespectful treatment of him. Woodard, in uniform, was arrested by the local police chief, Lynwood Shull, and beaten and blinded while in custody. President Harry Truman was outraged by the incident. He established the first presidential commission on civil rights and his Justice Department filed criminal charges against Shull. An all-white South Carolina jury acquitted Shull, but the presiding judge, J. Waties Waring, was conscience-stricken by the failure of the court system to do justice by the soldier and began issuing major civil rights decisions from his Charleston courtroom. Three years later, the Supreme Court adopted Waring’s language and reasoning in Brown v. Board of Education.

Richard Gergel’s Unexampled Courage details the impact of the blinding of Sergeant Woodard on the racial awakening of President Truman and Judge Waring, and traces their influential roles in changing the course of America’s civil rights history. What follows is an excerpt about Woodard’s trial and the ways in which the process was working against him from the start.

Jury selection in United States v. Shull began the next morning, Tuesday, November 5, at 10:30. The pool of prospective jurors, known as the jury venire, was all white, even though South Carolina’s minority population was approximately 40 percent, the highest percentage of any state except Mississippi. This was the product of the state’s systematic policies and practices of black disenfranchisement, because the jury pool was drawn from registered voter lists.

The defense attorneys for [Lynwood] Shull, Jefferson Davis Griffith and Jack D. Hall, wasted no time injecting race into the proceedings. Griffith was the elected solicitor, or chief prosecutor, for the state judicial district where Batesburg was situated and was one of the premier trial attorneys in the area. Hall was an attorney practicing in Batesburg. As jury selection began, defense counsel asked Judge Waring to inquire to the jury venire if any was “a member of the Association for the Protection of the Colored Race or any other association or organization interested in race relations.” Because the jury pool was all white, the possibility that any prospective juror might be a member of the NAACP or any other civil rights organization was somewhere near zero. To Franklin Williams’s [Thurgood Marshall’s assistant counsel, dispatched to keep an eye on the prosecution team] surprise, the government did not object to this question or request that the jury panel be asked about membership in the Ku Klux Klan or other similar organizations, a far more likely problem for the prosecution when drawing a jury at the time in South Carolina.

After Judge Waring went through his standard questions for jury qualification and asked the defense’s requested inquiry regarding NAACP membership, the court proceeded to jury selection. Both the prosecution and the defense had the right to make peremptory challenges, which allowed the dismissal of a limited number of prospective jurors without a stated cause. Court rules also allowed either party to move for the removal of a prospective juror for cause, which could include such reasons as racial prejudice or bias in favor of the white law-enforcement defendant. The defense made two peremptory challenges; the government made none. No requests for strikes for cause were made by either party. Williams, amazed and astounded by the government’s passivity in jury selection, wrote in his trial notes, “No [government] challenges at all!” He subsequently observed to Thurgood Marshall that the prosecutors seemed wholly unconcerned about who their jurors would be. Rogers [Justice Department’s special counsel] later claimed that he had deferred to [Claud] Sapp [Woodard’s lawyer] and his staff, who had reviewed the juror list and “concluded the jury panel would be fair to the government and the defendant alike.”

After the jury was selected, the attorneys made brief opening statements. The courtroom was packed, with white farmers and businessmen from Lexington County appearing in support of Lynwood Shull and black college students from nearby Allen University and Paine College attending in support of Isaac Woodard. To Williams’s irritation, Sapp mispronounced Woodard’s name in the opening statement, repeatedly referring to him as “Woodward.”

To Williams’s irritation, Sapp mispronounced Woodard’s name in the opening statement, repeatedly referring to him as “Woodward.”

Isaac Woodard was called as the government’s first witness. He wore a brown suit and green sunglasses and had to be led to the witness chair by court staff. Woodard described his disagreement that fateful evening with the Greyhound bus driver over his request to step off the bus during a stop to relieve himself. Woodard stated that the bus driver cursed him, and he cursed back, insisting that he “talk to me like I’m talking to you. I’m a man just like you.” Woodard testified that he was summoned off the bus at the next stop and came face-to-face with the police chief Lynwood Shull. He stated that when he attempted to explain what had happened, Shull struck him on the head with a blackjack, arrested him, and led him down the street to the town jail several blocks away with his arm twisted behind his back.

Woodard testified that after they had turned the corner and were no longer in sight of the bus stop, Shull asked him if he had been discharged from the army. Woodard stated that when he responded “yes,” Shull struck him a second time on the head with his blackjack, telling Woodard the correct answer was “yes, sir.” Woodard acknowledged that he then attempted to take the blackjack away from Shull to prevent any additional unprovoked strikes. He testified he was able to obtain control of the officer’s blackjack. At that point, he testified, another officer appeared with his gun drawn and demanded that Woodard drop the blackjack or he would drop Woodard. He testified that Shull regained control of his blackjack and furiously began beating him about the head until he was unconscious. Woodard stated that when he regained consciousness, Shull directed him to stand up. As he attempted to comply, Woodard testified, Shull drove the handle end of the blackjack into each eye repeatedly. Woodard stated he was then taken to the town jail, was placed in a cell in a semiconscious state, and drifted to sleep.

Woodard stated that when he awoke the next morning, he realized he could not see. He stated that Shull informed him that he had a trial set that morning in town court on the charge of drunk and disorderly conduct. Because he was unable to see, Woodard stated, Shull had to escort him to the nearby town courtroom. Woodard testified that he tried to explain to the town’s judge what had happened. Shull interjected that Woodard had attacked him. The judge responded that they did not allow such conduct around his town and promptly found Woodard guilty. He imposed a fine of $50 or thirty days on the chain gang. When Woodard was able to produce only $44 in cash, the balance of the fine was suspended and he was then free to leave. Woodard stated that he told Shull he felt ill and was escorted back to the jail, where he lay down. Later that day, when his condition did not improve, Shull transported him to the VA Hospital in Columbia, where he was left.

Woodard held his own on cross-examination from defense counsel, who mostly focused on the sergeant’s conduct while on the bus rather than his encounter with Shull. As defense counsel questioned Woodard, he referred to him as “Isaac,” a common custom at that time in which whites denied blacks the courtesy of addressing them as “Mr.” or “Mrs.” Woodard was pressed on cross-examination about whether he had been drinking on the bus and whether he had been so profane that a white passenger had asked the bus driver to remove him. The questioning suggested that if Woodard had been drinking on the bus, he later received a beating he deserved. Woodard denied drinking on the bus or using profanity beyond his exchange with the bus driver.

The government next called to the stand Dr. King, who described the physical injuries he observed when he examined Woodard in the jail on the afternoon of February 13, one day after he was struck by Shull. Clearly cooperating with the defense, King was asked on cross-examination by defense counsel whether Woodard’s injuries were possible with a single strike of a blackjack. After being handed a blackjack to examine, King offered the opinion that Woodard “could have” been blinded in both eyes with a single blow. Now in a position of having to challenge his own witness, Rogers asked King whether such an injury with a single strike was improbable. King admitted that Woodard’s blinding could have occurred with a single strike from the blackjack only with a “perfectly timed” blow.

The government then called the two VA doctors who examined Woodard, Dr. Arthur Clancy and Dr. Mortimer Burger. Both physicians provided clinical descriptions of Woodard’s eye injuries. The prosecutor did not, however, elicit from Clancy the opinion he had offered the FBI in a field interview that “the victim appeared to have been struck with more than one blow inasmuch as the bone structure surrounding the eye would make it rather difficult to strike both eyeballs at one time with one blow.” He also did not elicit from Burger the information he had given the FBI regarding the multiple facial injuries detailed in his physical examination report prepared on the morning of February 14. Such evidence would have supported Woodard’s testimony that he was struck multiple times by Shull and undermined Shull’s defense that he had blinded Woodard in both eyes with a single strike of a blackjack.

With the completion of Burger’s testimony, the government rested its case at 12:25 p.m., just one hour and twenty-five minutes after it had opened its case. Franklin Williams was almost apoplectic. The government had not called Jennings Stroud, the white veteran who had observed Shull strike Woodard unprovoked shortly after exiting the bus, or McQuilla Hudson, who was prepared to testify that Woodard was not disruptive or boisterous on the bus. Williams also realized that the government had never subpoenaed Woodard’s medical records from the VA, which he was confident would document more injuries than described by the doctors from the witness stand. In his handwritten notes made while observing the trial, Williams wrote, “Where are hospital records!! Why not subpoenaed? Gov’t rests!!”

With the completion of Burger’s testimony, the government rested its case at 12:25 p.m., just one hour and twenty-five minutes after it had opened its case.

Williams angrily confronted Rogers during a court recess, challenging his decision not to call Stroud and Hudson in the government’s case in chief. Rogers responded that it would be better to call these witnesses in rebuttal. In a criminal prosecution, the government is required to put up its entire case initially, in what is called the case in chief. The defendant is then allowed to offer evidence in his defense. The government thereafter is entitled to offer rebuttal or reply testimony, which must be evidence responding to the offered defense. Because the defendant is not allowed another opportunity to offer evidence after the government’s rebuttal stage, trial judges commonly place strict limits on the type of evidence the government can offer for the first time in the rebuttal phase. Thus, the prosecutors’ decision to hold back the testimony of Stroud and Hudson until the rebuttal phase of the trial was a very risky strategy with little seeming upside.

Williams also expressed astonishment to Rogers that the government had not obtained a copy of Woodard’s medical records. Williams asked Rogers for some explanation for this glaring failure to collect the most basic evidence in the case. According to Williams, Rogers’s response was “evasive and unsatisfactory.”

Shull’s defense team began their case by calling the bus driver, Alton Blackwell, as their first witness. Blackwell described Woodard as boisterous, drunk, and profane on the bus and stated he resolved to have the soldier removed after a white couple complained about his language. He also testified that Woodard put him behind schedule by repeatedly exiting the bus at each stop to relieve himself. On cross-examination, Sapp brought out inconsistencies between Blackwell’s testimony and his earlier sworn statement given to the FBI.

Agent [Ralph] House [FBI special agent], observing the trial from the audience, became enraged by Sapp’s cross-examination of the bus driver. During a subsequent court recess, House bitterly complained to Sapp that his questioning of Blackwell was misleading because any discrepancies between the bus driver’s statement to the FBI and his trial testimony were inconsequential. House contended that Shull’s lawyers had insinuated that the FBI had taken some liberties in preparing Blackwell’s affidavit. House asserted that the FBI had “received undue criticism and publicity about this case” from local law enforcement, and he wanted Sapp to protect the FBI’s reputation by having Blackwell’s full statement read into the record. To their credit, the prosecutors refused.

The defense next called Officer Elliot Long, the other half of Batesburg’s two-man police department. Long testified that he had personally retrieved Woodard from the bus and observed that Woodard was loud and intoxicated. He further testified that he appeared at the jail as Woodard arrived and there was no evidence that he had been beaten or injured in any way. Long also denied having pulled his gun on Woodard or being present when Shull beat him with a blackjack.

Long stumbled during cross-examination when he was confronted with his prior statement to the FBI that Shull, not he, had taken Woodard off the bus. Long attempted to explain this discrepancy by stating, “I studied the case and later learned that I did.” When pressed by Sapp for a better explanation, Long stated, “I didn’t have a chance to think it up.” With that curious response, the officer left the stand around 1:20 p.m., and Judge Waring recessed the trial for lunch until 3:00 p.m.

As soon as the trial resumed, Shull took the stand in his own defense. He described Woodard as intoxicated and loud when he came off the bus. Shull claimed he arrested Woodard not for his conduct on the bus but for his behavior at the bus stop. He denied striking Woodard at that point but stated that he took him by the arm and headed to the town jail a few blocks away. Shull testified that after he and Woodard turned the corner and were out of sight of the bus stop, Woodard suddenly attacked him without provocation. According to Shull, Woodard grabbed his blackjack, which was connected to Shull through a leather wrist strap, and the two struggled over control of the weapon. It was then, Shull testified, that he had struck Woodard a single blow with the blackjack. Shull explained that in the frenzy of the moment he had no opportunity to aim the blackjack and did strike the veteran in the head. Shull stated, “I had no intention of blinding him in the eyes. I merely struck him in my own defense. I could even have stuck my fingers in his eyes, but I couldn’t be sure, and in a similar scuffle, I don’t suppose anyone could be.” Shull concluded, “If my blow blinded him, I’m sorry. I hit him in self-defense, and to keep him off of me.”

Shull testified he then took Woodard to the town jail and the soldier gave no indication of having suffered any serious injury. The next morning, Shull stated, he took Woodard to the town court to be tried on a charge of drunk and disorderly conduct. Although one of Woodard’s eyes was swollen, Shull claimed, Woodard was able to see and function independently. According to Shull, Woodard stated that he “reckoned he drunk too much” and pleaded guilty to the charge. The judge fined Woodard $50, later lowered to $44 because that was all the cash Woodard had on him.

Shull testified that Woodard did not complain of an inability to see until after the town court proceeding. Shull stated that Woodard informed him he felt “sick at the stomach” and was allowed to return to the jail to lie down. As Woodard’s left eye became more swollen, Shull stated, he sought the assistance of the town physician, Dr. King, but King was then unavailable. Later, after King appeared and examined Woodard, Shull testified, he followed the doctor’s instructions and took Woodard to the VA Hospital in Columbia, some thirty-five miles away.

Sapp began his cross-examination of Shull by dangling Shull’s sworn statement to the FBI in the air and having him confirm he had given and signed the statement. Sapp then asked Shull if FBI agents would have any reason not to have recorded his statement accurately and completely. Shull responded that he did not think “those FBI boys would try to trick” him. Shull’s attorney, almost in a panic, came across the courtroom to where Sapp was standing and demanded that he be shown Shull’s prior statement. Judge Waring denied the defense counsel’s objection and ruled Sapp had no obligation to provide Shull with a copy of his prior statement.

There was a difference in Shull’s trial testimony and the sworn statement on the single-strike issue. In the FBI statement, Shull had stated that after he and Woodard turned the corner, Woodard refused to proceed any farther and Shull then shook his blackjack at him and “bumped him lightly with the blackjack on the side of the head.” Woodard responded to this, according to the Shull statement, by attacking him and trying to wrestle away the blackjack. Shull’s trial testimony was that there was only a single strike of the blackjack that had followed a surprising and unprovoked assault by Woodard.

When Shull was confronted with this inconsistency, he responded unexpectedly, by admitting that he struck Woodard with his blackjack at the bus stop. This is something he had consistently denied until that moment. Shull’s new admission did not go directly to the issue of whether he had brutally beaten Woodard into unconsciousness and then jammed the blackjack handle into his eyes, but his changing testimony about where and how many times he struck Woodard had the potential of undermining his credibility.

After having made a dramatic use before the jury of Shull’s prior FBI statement and obtaining a new admission from Shull about striking Woodard at the bus stop, Sapp gave it all away by announcing in a joking manner that the defense had nothing to worry about because Shull’s FBI statement and his trial testimony were “substantially the same.” Sapp’s statement produced widespread laughter from Shull’s supporters in the courtroom, but Franklin Williams was incensed. He believed that Sapp had intentionally undermined a legitimate point of inconsistency in Shull’s testimony in an effort to go soft on him.

Following Shull’s testimony, the defense called Batesburg’s mayor, H. E. Quarles, who doubled as the town’s judge. He testified that Woodard pleaded guilty at his trial and admitted he had drunk too much the night before. Quarles stated that Woodard was able to see and function independently and did not ask for medical attention. Another witness, G. C. Shealy, a local furniture salesman, testified he happened to be present at the town court proceedings on the morning of February 13 and heard Woodard plead guilty. This testimony was followed by four character witnesses, including the Lexington County sheriff, Henry Caughman, and a black contractor from Batesburg, Archie Beechem. After Beechem testified that he had known Shull for twenty years and stated that he treated black citizens “extra fine,” Franklin Williams wrote in his notes, “Judas.” At 4:30 p.m., the defense rested.

The government prosecutors then attempted to call Jennings Stroud as a rebuttal witness. Shull’s attorneys strenuously objected, arguing that such testimony should have been offered in the prosecutor’s case in chief and was beyond the scope of rebuttal evidence. Judge Waring sustained the defense objection, a not surprising ruling under the circumstances. Because the government elected not to issue a new subpoena to Lincoln Miller [eyewitness from bus] when the first subpoena was sent to the wrong address and failed to offer Stroud’s testimony in its case in chief, the jury never heard from two eyewitnesses who observed Shull’s unprovoked and violent striking of Woodard just as he stepped off the Greyhound bus.

The defense moved for a directed verdict of acquittal. Judge Waring denied the motion and directed counsel to present closing arguments. Special Counsel Rogers, leading off for the government, told the jury that he was a southerner, from Texas, and understood what they might feel about a civil rights case. He felt obligated to tell the jury that he was not a member of the NAACP. Rogers stated he was not ashamed of this assignment because he was an upholder of justice regardless of race and was convinced that Shull had acted “in pure malice.” After reviewing the evidence offered at trial, he asked the jury to return a verdict of guilty.

The defense counsel, Hall and Griffith, split their thirty-minute argument, unleashing a rash of racially charged arguments that Judge Waring would later describe as “pretty dreadful.” Announcing that the people of South Carolina resented this federal civil rights prosecution, Hall argued that “if a decision against the government means seceding, then let South Carolina secede again.” He argued that a guilty verdict would render nil the ability of law-enforcement officers to protect the public, which triggered an objection from the prosecutors and an instruction from Judge Waring that the argument was improper because law enforcement was not on trial. The defense further argued that Woodard belonged to “an inferior race that the South has always protected” and that Woodard’s admission that he spoke back to the white bus driver demonstrated he was intoxicated because “that’s not the talk of a sober niggra in South Carolina.” The defense argument concluded with a request that the jury return a verdict of not guilty.

Claud Sapp then stepped forward to make a brief final closing argument for the United States. He told the jury members he had fulfilled his duty as U.S. attorney by presenting this case and “whatever verdict you gentlemen bring in, the government will be satisfied with.” Departing from well-established custom, Sapp did not ask the jury to return a verdict of guilty.

Judge Waring charged the jury for twenty-four minutes, laying out the requirement that the defendant must be found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt and explaining to the jurors the legal requirements for a conviction under the civil rights statute. Acknowledging the controversy and publicity about the case, Judge Waring instructed the jury to disregard the opinions of various groups and individuals and what they might say about the verdict. Instead, he instructed the jury members to base their verdict on the evidence and not to consider race or the fact that the defendant was a law-enforcement officer. Referring to the closing argument by defense counsel to which he had sustained an objection, Waring told the jury that one man, not all of law enforcement, was on trial.

Judge Waring sent the jury out at 6:28 p.m. to begin its deliberations. In order to avoid the indignity of a five-minute verdict in the case, he advised the deputy marshal that he was going for a walk and would return to the courthouse in twenty minutes. The marshal replied, “But, Judge, that jury ain’t going to stay out for twenty minutes.” Waring responded, “They’re going to stay out twenty minutes because they can’t come out until I come back, and I’m not going to be back for twenty minutes.”

In order to avoid the indignity of a five-minute verdict in the case, he advised the deputy marshal that he was going for a walk and would return to the courthouse in twenty minutes. The marshal replied, “But, Judge, that jury ain’t going to stay out for twenty minutes.”

Waring took a leisurely early evening walk in downtown Columbia, returning to the federal courthouse twenty-five minutes later. He was advised that the jurors had been banging incessantly on the jury room door, insisting they had reached a verdict. At 6:56 p.m., twenty-eight minutes after they had filed out of the courtroom to begin deliberations, the jury returned to the courtroom, and the clerk published the jurors’ unanimous verdict of not guilty. As Shull’s supporters celebrated, few noticed Elizabeth Waring quietly leaving the courtroom in tears. A disappointed Isaac Woodard told Franklin Williams that “the right man hasn’t tried [Shull] yet.”

In the weeks following the acquittal, civil rights activists criticized the performance of the government prosecutors in United States v. Shull. In a letter to Attorney General Tom Clark on November 14, 1946, Thurgood Marshall asserted that there was a “failure vigorously to prosecute” Shull by U.S. Attorney Sapp and Special Counsel Rogers. He pointed to the prosecutors’ failure to request that the judge inquire into prospective jurors’ affiliations with the Klan or other segregationist organizations and to Sapp’s failure to ask the jury to return a verdict of guilty. Instead, Marshall observed, Sapp told the jury that the government would be “satisfied with whatever verdict the jury should return,” which Marshall said was “an invitation to the jury to bring in a verdict of acquittal.” The legendary civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph wrote to Clark, criticizing Sapp’s failure to request a verdict of guilty and the prosecutors’ failure “to place on the stand two eyewitnesses who saw Woodard beaten.” An article in The Pittsburgh Courier of November 16 voiced some of the same criticisms and also referenced the prosecutors’ failure to exercise any of their peremptory challenges.

There was considerable merit to the criticisms voiced by the civil rights community. A good example was the government’s failure to request that Judge Waring ask the jury panel questions about potential bias or to exercise any of its preemptory challenges. The Justice Department’s decision to charge Shull only with a misdemeanor (and thus avoid presentation of the case to an all-white South Carolina federal grand jury for a felony indictment) was based on the assumption that there was so much local bias that the grand jury would likely refuse to return an indictment. In light of that reasonable assumption, the failure to request that the judge carefully question the jury panel about bias is inexplicable. Similarly, Sapp’s failure in his closing argument to ask the jury to return a verdict of guilty and his suggestion that the jurors do what they thought was right clearly communicated that he had no expectation of a guilty verdict.

The prosecutors also blundered in failing to present in their case in chief the eyewitness testimony of Jennings Stroud and Lincoln Miller that they observed Shull inflict a serious and unprovoked blow to Woodard’s head moments after the soldier stepped off the bus. This testimony was certainly in conflict with Shull’s claim that he had struck Woodard once and only in self-defense, and suggested a level of animus and gratuitous violence by Shull inconsistent with his FBI statement and trial testimony. The eyewitness testimony of the soldiers on the bus was never heard by the jury because of the ill-advised decision to hold Stroud’s testimony until the government’s reply, clearly a risky move, and the failure to locate Miller after his first subpoena was sent to the wrong address.

There is little question that Woodard’s insistence that he was not drinking on the bus presented practical problems for the prosecutors. But this was not a case charging Woodard with consumption of alcohol on a bus, and all of the soldier witnesses on the bus, both black and white, told the FBI that Woodard was not disruptive or obviously intoxicated. The investigating FBI agents and Special Counsel Rogers obsessed over the dispute about Woodard’s drinking on the bus, suggesting that if Woodard’s pre-assault conduct was not perfect, Shull could not be culpable for the use of excessive force. The critical issue was not whether Woodard had been drinking before his arrest but whether Shull had used excessive force after taking Woodard into custody. This very point was made by James Hinton, the South Carolina president of the NAACP, shortly after the trial when he stated in a letter to the editor of The State, “We have no hate for Mr. Shull, nor do we condone any wrong Isaac Woodard might have done, but we do know that more physical force was used against the veteran than was necessary.”

In the end, the fundamental flaw in the government’s prosecution of Lynwood Shull was the FBI’s failure to determine through independent medical experts the nature and amount of force actually used by Shull to blind Woodard. Common sense suggested that Shull’s claim of a single defensive strike to the head producing bilateral blindness was improbable. Initial interviews with Woodard’s VA doctors certainly raised doubts about Shull’s single-strike claim. But despite these important leads, the FBI failed to obtain an independent specialist evaluation of Woodard, which would have revealed that the globes of both of his eyes had been crushed, something that a single strike to the head under these circumstances could not have produced. The prosecutors also failed to have the medical evidence in the case assessed by forensic medical experts, who could have reconstructed the nature and number of strikes necessary to produce Woodard’s injuries. The most advanced forensic department then existing in the world, the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, was located just blocks from the Department of Justice in Washington and could have been called upon by prosecutors or FBI agents to assist. The agents’ failure to obtain a copy of Woodard’s VA Hospital records, an essential starting point to investigate the cause of his blindness, speaks volumes about the FBI’s myopic and incomplete investigation.

The harshest critic of the government’s prosecution, Judge Waring, held his tongue at the time but after his retirement shared with a historian a devastating critique. Waring described the government prosecutors as ill-prepared and the investigation far from thorough. He stated, “I was shocked at the hypocrisy of my government . . . in submitting that disgraceful case before a jury [and was] hurt I was made a party to it.” Waring was convinced there was a stronger case that could have been presented. He acknowledged, however, that he was not sure there would have been a conviction before an all-white federal jury in South Carolina in 1946 even if the government had presented twenty eyewitnesses.

Waties Waring returned to his hotel room the night of the Shull verdict deeply troubled about the trial. He found his wife tearful and emotionally traumatized by the events of that day. Having lived a life of privilege, shielded from the underbelly of southern racial practices, Elizabeth Waring struggled to process what she had just witnessed. For his part, Waring was “tortured” by the fact that a police officer, who had appeared to be a “fine young man,” inflicted a vicious beating on a returning American soldier and that the criminal justice system had failed to hold the police officer accountable. Elizabeth Waring bluntly told her husband she had never heard or seen such a “terrible thing” and privately shared her distress with a South Carolina–born friend a few days later. The friend responded, “That sort of thing happens all the time. It’s dreadful, but what are we going to do about it?”

Judge Waring would later describe the Shull trial as his wife’s “baptism in racial prejudice” and his own “baptism of fire.” It was a transformative event in the life of the Warings, causing them to see and sense the world around them in a fundamentally different way. The world of Jim Crow now suddenly came into focus. For the first time in his sixty-six years, Waties Waring began to doubt his basic assumptions about the southern way of life. Responding to the question of Elizabeth’s friend, “What are we going to do about it?,” the Warings began a period of serious study and reflection on the issue of race in America and a federal judge’s personal responsibility to uphold the rule of law. This period of study and introspection would take Waties Waring on a journey in which he ultimately resolved that it was his sworn duty to boldly and forthrightly confront racial injustice, whatever the personal consequences. Soon he would begin issuing landmark civil rights decisions that would shake the political foundations of his native state and alter the course of American history.

In the summer of 2018, the town of Batesburg-Leesville reopened the case of Isaac Woodard, officially acknowledging the facts of what happened to him, and expunging his record. This Saturday, February 9th, at 11am, the town will host a ceremony to unveil an historical marker to honor the memory of Woodard and his importance within the broader history of the civil rights movement. Those involved in the event will walk the path from the spot where Isaac Woodard was removed from the bus, around the corner to where he was beaten and blinded, to the former location of the town jail and court, where the historical marker will be dedicated.

Richard Gergel is a United States district judge who presides in the same courthouse in Charleston, South Carolina, where Judge Waring once served. A native of Columbia, South Carolina, Judge Gergel earned undergraduate and law degrees from Duke University. With his wife, Dr. Belinda Gergel, he is the author of In Pursuit of the Tree of Life: A History of the Early Jews of Columbia, South Carolina.