When I began researching Bringing Down the Colonel some ten years ago, I was confident that I was writing “history.” I hoped that by telling the story of a lost, late Gilded Age sex scandal, I could shed light on how far women had come in terms of being judged by metrics other than their sexual respectability. I also wanted to offer a warning about the increasing tendency by some to try to recapture the “good old days” of strict sexual morality that depended on shaming women for their sexual choices.

But sometimes, it seems, history doubles back on itself like a particularly testy snake trying to eat its own tail. By the time I actually sat down to write Bringing Down the Colonel, events in the present were beginning to collide with the past in ways that made me rethink my assumption that what I was writing about was safely in a bygone era.

In 2015, Monica Lewinsky went public with her reassessment of the scandal that resulted from her involvement with then-President Bill Clinton. “I was Patient Zero of losing a personal reputation on a global scale almost instantaneously,” she said in a TED Talk that was viewed nearly 14 million times. As Lewinsky recounted how she as a vulnerable young woman was shamed by those who should have been her allies—including progressive Democratic women—I couldn’t help but compare her to Madeline Pollard, the protagonist of my book. Like Lewinsky, Pollard was a young woman in a precarious position who was seduced by the heady perfume of power and romantic promise emanating from a charming, prominent southern Democrat—and who, like Clinton, was married and much older.

Going public as a “fallen” woman—a woman who was outed as having had sex outside of marriage—was shocking for the time.

Unlike Lewinsky, however, Madeline Pollard grabbed hold of the narrative from the start—so much so that it was she who disclosed the affair after her paramour, Congressman and Colonel William Campbell Preston Breckinridge, threw her over for a woman with higher social standing. Going public as a “fallen” woman—a woman who was outed as having had sex outside of marriage—was shocking for the time. But surprisingly for 1894, other women, both progressive and conservative, rallied behind her and agreed that she had been the victim of predation by an older, powerful man, bucking the social convention that it was “ruined” women who were predators. They helped her serve Breckinridge his comeuppance of losing a high-profile breach of promise trial that made headlines across the country by funding Pollard’s quixotic quest for justice. And they pressured the men in their lives to reject him in a tensely fought primary battle, stripping him of a congressional seat that was practically his by birthright into the southern elite.

Just months later, I would write one of the most painful chapters in the book—the story of how Grover Cleveland raped a respectable young widow named Maria Halpin, then covered up the resulting pregnancy by stealing her child and trying to have Halpin committed to an insane asylum and sashaying into the White House eight years later, portraying her as a “bad” woman. It was at that time that thirty-five women who’d accused Bill Cosby of sexual assault appeared together on the cover of New York magazine, illustrating the scale of the abuse inflicted by a single, conniving, powerful man and revealing how women are systematically silenced by a culture of disbelief.

By the time Donald Trump was elected president, I no longer felt like I was writing history, just a parallel story of women who happened to be born in another time. I wrote the chapter about the great uprising against Breckinridge by the upper-crust women of his home district of Lexington, Kentucky, during the days leading to the historic Women’s March in Washington. “By your attendance or your non-attendance you are setting up your own history,” the leaders of the movement warned the women in urging them to abandon their household duties to attend an anti-Breckinridge rally. I wrote about trains into Lexington being packed with women headed to the rally in that spring of 1894 as my own streets began to fill with women just off the Metro headed for the Women’s March. Thousands of footsteps echoed throughout the city as I recounted how the Lexington ladies “fairly shook” the packed Lexington Opera House, “clapping their hands and rapping on the floor with their umbrellas” as speaker after speaker rallied against Breckinridge and the double standard he exposed.

By the time of the Kavanaugh hearings, excuses and justifications from the past were repeating and echoing in the present in a kind of historical slipstream. “What about his family?” people asked of Kavanaugh. “Think of his wife and daughters,” they pleaded as I wrote about Madeline on the stand at the pinnacle point of the trial, as one of Breckinridge’s lawyers, himself a prominent former congressman, badgered her about her ruination and her decision to go public. Wasn’t it true, he asked, that a nun at the asylum where she had taken refuge after she became pregnant with Breckinridge’s child later told her she was a bad woman and “pleaded with her to consider Breckinridge’s daughters?”

“I said he did not consider me and I was somebody’s daughter, and that he did not consider the little daughter of his and mine whom he had compelled me to give away,” Madeline cried. Another of Breckinridge’s lawyers warned that jury that finding for Madeline would “encourage every strumpet to push her little mass of filth into court,” as some on my television screen argued that Christine Blasey Ford should be ashamed of herself for maligning a good man like Brett Kavanaugh and sullying the Supreme Court.

“Throughout history, women have been traduced and silenced. Now, it’s our time to tell our own stories in our own words.”

“Throughout history, women have been traduced and silenced. Now, it’s our time to tell our own stories in our own words,” Monica Lewinsky wrote recently about her decision to participate in the A&E docuseries “The Clinton Affair.” Maria and Madeline can’t tell their own stories. But I hope by bringing their stories to light, the shaming and silencing of women someday may truly be consigned to history.

Patricia Miller is a journalist and an editor who has written extensively about the intersection of politics, sex, and religion. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Salon, The Nation, The Huffington Post, RH Reality Check, and Ms. magazine. She is a senior correspondent for Religion Dispatches, where she writes about the politics of sexuality and the Catholic Church. She was formerly the editor of Conscience magazine and the editor in chief of National Journal’s daily health-care briefings, including the Kaiser Daily Reproductive Health Report and American Healthline. She has a master’s in journalism from New York University and is based in Washington, D.C.

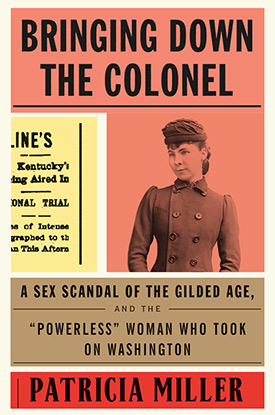

Patricia is the author of Good Catholics: The Battle Over Abortion in the Catholic Church and Bringing Down the Colonel: A Sex Scandal of the Gilded Age, and the “Powerless” Woman Who Took On Washington.