Dramatizing the eternal dispute between poetry and power, faith and practicality, haves and have-nots, Dror Burstein’s Muck is a brilliant and subversive retelling of the book of Jeremiah. In a Jerusalem both ancient and modern, where the First Temple squats over the populace like a Trump casino, where the streets are literally crawling with prophets and heathen helicopters buzz over Old Testament sovereigns, two young poets are about to have their lives turned upside down.

Head shaved, bandaged, and with a broken keyboard, Jeremiah rode the light rail to his parents’ home. Only six months ago, he’d rented an apartment on Ha-Yarmukh Street, and he still hadn’t moved all his books and belongings into his new place. In order not to have to answer the likely questions about his bruises, he crawled through the window. He sat at his desk and thought of writing something, but he couldn’t write without the keyboard. He’d just about forgotten how to write by hand and was ashamed of his handwriting, which seemed to him like the scrawl of a nursery-school child. He sat there in front of the desk, mortified by the anguish Broch had caused him. Outside, he could see through the window the new, fierce star that glowed in the bright midday light. Several days ago, its light had become visible even at noon. They said that its diameter during its lifespan was 440 times the size of the sun, and that if it had been positioned at the center of the solar system its outer fringes would have licked the dust between Mars and Jupiter. Now, having exploded at the end of its days, it shone almost like a bright full moon. After the initial excitement, no one took any notice anymore—how long, after all, can one go on applauding a ruined star?

He peered for a long time at the dead red giant. And he dozed off upright in his chair in his parents’ home in the ancient village of Anatot, just north of Jerusalem, at four o’clock in the afternoon. He didn’t know whether his parents were home. Silence reigned in every room, or might his ears have been closed to their voices and movements? And the silence was as long as the night. But the following morning he woke to the sound of a voice at dawn. The star was still there, a strong and steady and distant light, and Jeremiah didn’t think it strange that the star hadn’t budged from its place, even though, after all, it was supposed to have set by now, off to shed its light on others. Not until several hours later, when he’d have taken out his notepad and jotted down from memory what he’d been told in the early-morning hours, would he somehow succeed in understanding what had been said, its meaning and purpose, where the voice was leading, and what it was demanding of him. When the voice spoke, the words seemed transparent, verging on music, like a song in a foreign tongue that you marvel at but must translate in order to grasp fully. Before I formed you in the belly I knew you, and before you came forth out of the womb I sanctified you, the voice said, I have appointed you a prophet to the nations. And Jeremiah didn’t understand what was said to him, and what was happening. Mutely, his body shouted: What? What?

When the voice spoke, the words seemed transparent, verging on music, like a song in a foreign tongue that you marvel at but must translate in order to grasp fully.

It was a little less than an hour after the voice had addressed him before he opened his mouth to answer. I was very late in answering, he would think later. He figured he’d speak to the open window, since he didn’t know where else to reply. The rolling hills between Anatot and the length of Wadi Qelt loomed out of the dark beneath the star as though in evening prayer. For a moment Jeremiah felt like giggling and switching on the light in order to have done with all this, but he sensed that the matter was serious, even if it wasn’t the first time he’d heard such a voice. Some ten years ago, in the middle of summer camp—or, to be more precise, in the middle of a youth science club at summer camp—when he was thirteen, he’d ignored the voice, he’d shut his eyes and covered his ears with the palms of his hands, closed his mouth tight, and not answered, and the voice had finally desisted.

Jeremiah recalled what he’d said, back then, with his mouth closed, in the summer camp: Ah, Lord, behold I cannot speak, for I am a child. And since he had nothing else to say, he said it now as well, aloud. But now he was twenty-two. And right away, from behind him, an answer was heard. Do not say: I am a child, said the voice. And Jeremiah answered, But I’m scared. He meant to say that he was scared of whomever he was talking to; that he was afraid of turning his head and seeing who was speaking, and most of all afraid of the possibility that he wouldn’t see anyone there. But the voice pretended not to understand what exactly was frightening Jeremiah, and said, Do not be afraid of them, for I am with you to rescue you. And Jeremiah recoiled in fear—to rescue you? He opened his mouth to answer and shut his eyes. The torn star rose in the darkness of his closed eyes, and in the darkness that descended on him he felt a coarse hand touching his mouth, like Grandpa had touched his mouth a long time ago, when he worked as a steelworker, and the voice said—this time emanating from within the hand itself—Now I have put my words in your mouth. See today I appoint you—the voice began, and Jeremiah continued, in his own voice, as though he were reciting a portion of the Bible he’d learned back in elementary school—over nations and over kingdoms. To root out and to pull down. To destroy and to overthrow. To build and to plant.

Then: silence, as though everything had already been said, and it was possible to start walking on the trail the words had blazed and would continue to blaze. Jeremiah hadn’t noticed it yet, but his voice changed at that very moment; his voice would be from now on the voice of him who’d spoken to him, as if he’d been trying to mimic the voice and his voice had gotten stuck that way.

The sun’s outer rim edged over Anatot, and light from the new star faded. When Jeremiah opened his eyes, he found himself in the botanical gardens on Mount Scopus, overlooking his parents’ home from on high. He didn’t remember going up there and told himself, I must have been transported by some other means. He gazed at a branch without flower or fruit or leaf, directly in front of him. Am I still dreaming? Jeremiah asked, and the voice shot back, What do you see, Jeremiah? And Jeremiah said, I see the branch of an almond tree. And the voice said, You have seen well. And after some time—during which the bough grew three meters high and branched out and put forth serrated leaves and white flowers and a green fruit and roots of its own, and swarms of bees alighted on the flowers and flew off and returned, and sweet, irrigating waters streamed by in rivulets, and fish swam in the waters, and insects kicked at their reflections in the water, and all of nature reeled around him and around the tree—the voice went on to explain: For I am watching over my word to perform it. The almond tree faded away and shortly reappeared and grew transparent inside Jeremiah’s body and blossomed inside his head. When he opened his mouth to say something, a bitter almond stuck to his tongue. He had a locket with a snapshot of a girl he’d loved a long time ago; they were photographed together over there, in the bookstore above the lake. He’d dreamed once that he was walking beside her in an almond grove, and everything was white, even the mountain that towered beside them. And once he dreamed that there was someone else in the dream, someone chasing them both. Jeremiah placed the almond from his tongue inside the locket and snapped the lid shut. He didn’t even think it strange that the locket was the exact shape and size of the new almond, as though it had been given to him by the girl he’d once loved with the certainty that a day would come. A Piper plane flew overhead and skywrote a message in dreadful pink. But the message was in Akkadian, and Jeremiah was unable to decipher the cuneiform contrail.

He turned to stare at the new neighborhoods of North Jerusalem and beheld above the homes a hovering circle of stainless steel. At first he thought it was the new star, but, no, it was a pot, similar to the old saucepans his mother used. And it was obvious that the gigantic pot was seething even though it was empty. The pot had no handles and was ashen, like the setting sun. Indeed, the sun, the star, and the pot all shone in the sky, a blazing trio. Flames approached the pot and singed its silvery metal. Its bottom was pointing north, as if a fire there were bringing its formless contents to a boil. Crows cawed under Jeremiah’s feet. The pot glared at him, and though the pot had no eyes or mouth or nose, it was clear that it was gaping at the city, too. From within the locket, from within the almond, the voice burst out, now speaking into Jeremiah’s chest. It asked, the way someone shut in a cave might ask whoever is outside: What do you see, Jeremiah? And Jeremiah answered, I see a seething pot, tilted away from the north. And in a split second he understood and explained to himself, and the words in his mouth were as red as a burn: Out of the north calamity shall break out on all the inhabitants of the land. He looked north and east. He didn’t see a thing there, only the village where he was born, Anatot, and deserted Ramallah. A wind swept through the botanical garden, causing all the branches and leaves to sway for several moments at precisely the same angle, in unison. Jeremiah covered his eyes to protect them from the whirling cloud of dust.

• • •

A bearded soldier with a gas mask strapped to his face sat next to him, reading a book on the train from Ammunition Hill to the center of town. Jeremiah fell asleep, and the soldier, who was in the window seat, shook him awake. He wanted to get off, and told Jeremiah, moments before they arrived at the Shimon Ha-Tzaddik stop, as if striking up a casual conversation: But you gird up your loins, stand up and tell them everything that I command you. Don’t break down before them, or I will break you before them. Jeremiah didn’t catch the sudden, insinuated threat in the soldier’s words—in fact, none of it made much sense to him. He wanted to reach out and touch the soldier, but something kept them apart. The car reeled from side to side, and Jeremiah heard: And I for my part have made you today a fortified city, an iron pillar, and a bronze wall, against the whole land. They will fight against you, but they shall not prevail against you, for I am with you to save you. To save? Jeremiah wanted to ask. Save how, and from what? He opened his eyes in the empty car, and the conductor stood impatiently before him, holding a bottle of water, intending to empty its contents on him to wake him up; and Jeremiah slumped for a moment on top of the book the soldier had forgotten when he left the train car, murmured an apology, crossed the tracks, and entered another train, which was traveling in the opposite direction, just as it slid into the Mount Herzl stop, arriving from Ein Karem and grinding to a halt, its doors whooshing open, seemingly just for him. Someone said, Get in. And someone else grumbled in the crush of commuters.

A new prophet, whom Jeremiah hadn’t noticed before, was standing and prophesying there on the light rail from Mount Herzl to the center of town. The prophet was very young, maybe twelve years old. Prophets seemed to be getting younger and younger lately. As the strength of the Babylonians rose in their distant land, according to rumor, so, too, did the strength of the prophets in Judah. Who would have believed that the walls of the everlasting Assyrian Empire would one day crack? Prophets came and went, prophesying the ruin of its capital, Nineveh, but Nineveh stood like an elephant with a hundred legs, and everyone took for granted that it would remain standing, more or less, in perpetuity. The prophets shouted till they were hoarse, but the walls of Nineveh only grew thicker, and while the prophets foamed at the mouth, the Assyrian army only added more legions, and more kingdoms knelt at their feet and bowed to and fro seven times, as was the custom. Nineveh was a large city, a three-day walk—that is to say, it took three days to circumnavigate its walls on foot, but no one ever crossed Nineveh on foot, since it had a nonstop express subway that made the rounds in ten minutes flat and operated day and night. It was said that it never paused in its journey.

We need lots of money, of course, the twelve-year-old prophet said, as the light rail headed east. Without money, how are we going to stand against the Babylonians, also called the Chaldeans, that most bitter of nations? Ladies and gentlemen, it was revealed to me, and I beheld in the skies cuneiform inscriptions, and they soared above the skies of Jerusalem in shades of pinkish red, and they seemed to me like sticks, and they seemed like pins, and I interpret them now as swords thrust into the flesh of a captive. Between the two rivers they write on clay and they bake the writing in fire, and the writing isn’t destroyed but, rather, hardens. It isn’t like Egyptian papyrus, the prophet sneered, where all it takes is one match to burn down an entire library. They might use the same old form of writing the Assyrians used, but their words will be sharp and new, like razors on our necks. With the Babylonians, the prophet called out, the wilder the fire, the firmer the writing; every conflagration preserves their writings for another hundred years. In other words, prepare yourselves for fire, prepare yourselves for a sweeping conflagration. It won’t be long before you’ll be pining for the Assyrians. It’s an enduring nation, the Babylonians, it’s an ancient nation, a nation whose tongue you know not, nor will you understand what they say; their quiver is an open grave, the prophet rejoiced, they are all mighty men. Shemayah, we’ll buy them off, shouted someone in a black suit, who’d recognized the prophet, or we’ll shut ourselves up in our fortresses. And the prophet—whose name was indeed Shemayah, nicknamed Shemayahu the Phantasmer, after the dreams that assailed him—answered, Bah, shyster, they don’t need your gold, they’re just passing through here on their way to Egypt; they crave Egypt’s gold and all its produce; they’ll run over you like a race car squishing two dung beetles on a highway. In this parable, the prophet hastened to explain, you’re the beetles and you’re the dung. Jeremiah closed his eyes and leaned his brow against the windowpane of the car as it came to a halt at the central station. No one got out, no one boarded. He could see, in the darkness of his tightly shut eyes, both his parents marching in a long procession northeast, and then he stood and moved toward the exit door without opening his eyes. The young prophet noticed him and roared while pointing in his direction, Ho-ho, a false prophet riding the light rail, or, better yet, the blight rail—what better for a false prophet with maggots crawling in his rotting carcass—a blight on this false prophet and all his gibberish! The doors slid closed, and Jeremiah, who hadn’t had time to slip out, sat back down. The prophet’s words frightened him, and he gasped, short of breath. The little prophet grabbed a Coke can from the car’s vending machine and flung it at Jeremiah; the can hit the bandage Broch had wound around his head, and a nauseating pain shot through the wound. As the light rail continued on its way, the prophet stretched his hand out, and, as if by magic, the Coke can shot back to him again. A miracle, a miracle, the passengers shouted in the car. Amazing, did you see how he charmed the can? In order to purchase something, of course, we must pay for it—the boy prophet approached Jeremiah from behind and placed his hands on his shoulders—we buy, and, having bought, need more money, he explained reasonably; it’s like Economics 101. It seemed to Jeremiah that the prophet had sprouted into a young man in his twenties as he continued: One needs money in order to cover one’s expenses, and, incidentally, that’s why it’s always worth having more of it. Money goes to money, money begets money, money sticks to money, and also the glue that glues money to money is made of money. I’m speaking the truth, hear ye and hearken, he said. When I say money I mean cash money and not silver, even though silver also has a fixed value. But what’s the value of silver today? Twenty dollars an ounce—that’s trash, that’s trash, that’s traaash, he shouted. I sold a ton of zinc for seventeen hundred dollars, the prophet said, and he ground his teeth in rage. I bought zinc stocks, and the zinc zonked me. I’ve been zinczonked, zinczonked with bitter herbs and tears. Oh, light rail! he suddenly exclaimed, Don’t call yourself light but blighted, blighted gold on the way to the Holy Temple, empty your pockets of gold and of precious polished stones into the prophet’s hat!

Money goes to money, money begets money, money sticks to money, and also the glue that glues money to money is made of money.

Purses were drawn, and cash and coins and rings and earrings were flung in the direction of the hat as it made its rounds the length and breadth of the car. The hat fluttered back and forth in the car like a caged dove, and Jeremiah was taken aback. He was on the verge of throwing up. Hunched over, all he saw was a thicket of legs, and his head ached under the bandage, and he felt as though a dentist were filling one of his teeth without anesthetic. A one-hundred-shekel bill suddenly dropped in front of him, and without thinking twice he grabbed it and stuck it in one of his socks. Give me one hundred thousand today, and tomorrow you’ll receive sixty million in return, Mister! the prophet cried out. How are you going to fight against Babylonia without big budgets? Weapons aren’t free, weapons aren’t even cheap, iron chariots are expensive, Egyptian bows aren’t bought for a song, a Philistine pike costs a mint, and you’re not going to buy nuclear submarines in exchange for three black goats. What, you think you can get a free ride in this world?! he roared. No such thing as a free ride, several passengers answered in alarm, and someone said, Amazing, the rhetorical skill of this guy—you’d think his tongue was coated in honey. Show me the exchange rate and I’ll prophesy for you on the sword and on death. We’ve got to believe in money, for what else do we have left? We’ve got to believe that money will bring us enormous benefits, that he who doesn’t invest won’t see any gains, that he who doesn’t give his money a chance will be frowned upon by fortune! Happy are those who give their money free rein, the prophet proclaimed. We must give our money the chance to burn if we want interest to rise from its ashes. The market’s unstable, he said, you’ve got to know how to read the market. Prices skyrocketed on the spot; passengers placed their shopping bags filled with vegetables at the prophet’s feet, amazed by the soaring expenses; someone who looked like a beggar in a headscarf stuck a sesame-seed bun in the prophet’s hand, and he miraculously turned it into a savory stuffed pastry and ate it on the spot. The light rail reeled as it passed the Jaffa–King George intersection, and the electronic board announced in Arabic—although ages had passed since anybody had heard this tongue spoken in Jerusalem, they hadn’t succeeded in reprogramming the recording—Jaffa Center, and Jeremiah had just enough time to catch sight of the billows approaching and crashing against the doors and windows, and clouds covered the skies above Jaffa Road, clouds as one finds in the heart of the seas, when lightning strikes and a mighty torrent pours down on deck and on the coiled hawsers, and your sails are nearly torn to shreds in the astonishing winds. Jeremiah turned ashen and opened his mouth to puke, but nothing came up save the scent of almond, which wafted around him, and he clasped his locket as though he were drowning and clinging to the anchor chain for dear life, and remembered Jonah the prophet, who was a distant cousin on his mother’s side: Take me up and cast me forth into the sea, so shall the sea be calm unto you, for I know that for my sake this great tempest is upon you. And the young prophet yowled, And it shall be unto you a sign, my words have shaken the foundations, and your cursed light rail is reeling toward the sea. Nine hundred billion yen, he thundered, four thousand ounces of gold. Gems! the prophet shouted. Idiots! We’ve got to conquer everything right up to the Tigris, he proclaimed. You’ll rule over the Euphrates, he promised an old man, we’ll abolish that ugly cuneiform of theirs, we’ll impose our own script. And now the prophet’s head was within sniffing distance of Jeremiah’s, close up, low, practically on the floor, and the veins on the prophet’s temples were red and swollen, and someone smashed a window with the little red fire-hammer, because it had gotten so stuffy in the car, and salt water came crashing in and struck both their heads, and the prophet told Jeremiah in a whisper, as water streamed like a river through the car and over the entire lightrail system, barely containing his hatred: What do you propose for them? As for death, death, right? And as for the sword, the sword? This they’re already familiar with, this they’ve already been told a hundred thousand times over, better leap into the river and get out of my face or I’ll cut you up bad. The prophet stood up and shook himself. Prophesying seemed to add to his years. All at once he was old. The veins at his temples bulged and turned gray and pounded like pistons. Stooped over with years and rage, he waded in the water above the baskets of vegetables, grabbed an oversize carrot, and, crushed between the passengers holding on to the handles and bars, swam vigorously against the current back to Jeremiah and thwacked him on the head with the carrot, again and again, as if it were a truncheon. Jeremiah’s bandage fell, the brine ate at his open wound, and for a moment he lost consciousness. The prophet noticed Jeremiah’s dangling locket and, with an ear-rending scream, tried to seize it and tear it away from Jeremiah’s neck, but Jeremiah steadied himself and scrambled on top of the vending machine and slipped his locket back under his shirt, though in doing so he once more left his head undefended, and the prophet wasted no time before landing another blow. Jeremiah fell into the streaming water and tried to extricate himself, but the now old man kicked him in the shins, and when Jeremiah doubled over, he kneed him in the face, after which Jeremiah again fell back into the river coursing through the entire length of the commuter train, and he went under for a split second and then bobbed back up. The passengers looked on avidly from their seats. They were approaching the City Hall stop. Barely a day went by without some squabble or other between prophets on the light rail—they were basically hoodlums; they liked to smash up idol-worship conclaves just for the hell of it—and the transit officials were all fed up: Go ahead, see if you can tell the difference between a false prophet and a true one, a burly inspector told his colleague, leaning against a ticket validation machine. Jeremiah tried to flee, but the car was jam-packed. His clothes were soaked in brine, the river was a salty seawater river, and so, too, were the old prophet’s hair and garments soaked through. And the still-aging prophet would have struck Jeremiah yet again with his shaking white hand if the doors hadn’t finally slid open, and Jeremiah hadn’t forded the river, which had turned as shallow as trickling sewage. And he was shoved and jostled as he strode out, drenched, toward the City Hall Plaza, where he stood in the sun, bewildered, and dripping wet. The Phantasmer kept on beating feebly with his carrot at the train car’s window, until the same burly inspector strode up to him and socked him in the face with his inspector’s brass knuckles, sheathed in fake leather and stamped with the company seal, and the prophet collapsed on the spot like an inflatable mattress slashed by a razor. Passengers were boarding and disembarking, and after several moments all that was left of the mattress were a few plastic shreds sticking to soles and heels, dispersed all along the aisle of the mudsplattered train car, which would be hosed down in the evening; later, the shreds would scatter even farther afield, over sidewalks and lanes, and onto doormats at the entrances to Jerusalem homes.

Go ahead, see if you can tell the difference between a false prophet and a true one.

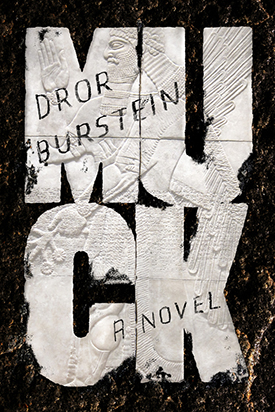

Dror Burstein was born in 1970 in Netanya, Israel, and lives in Tel Aviv. A novelist, poet, and translator, he is the author of several books, including the novels Kin and Netanya. He has been awarded the Jerusalem Prize for Literature; the Ministry of Science and Culture Prize for Poetry; the Bernstein Prize for his debut novel, Avner Brenner; the Prime Minister’s Prize; and the Goldberg Prize for his 2014 novel, Sun’s Sister.