“I’ve lived so many places it’s ridiculous . . . and because I moved so much, place is very, very important to me. I’m always looking . . . looking for home.”

—Lucia Berlin, interview (2003)

The first writer I ever watched at work was my mother, Lucia Berlin. My earliest memories are of my brother Mark and me riding our tricycles around our Greenwich Village loft while Mom pounded away on her Olympia typewriter. We thought she was writing letters—she wrote a lot of letters. On our long walks around the city, we would stop at a mailbox almost every day, where she would let us drop her envelopes through the slot. We loved to see them disappear and hear them fall. Whenever she received a letter, she would read it to us, often making a story out of whatever had been delivered that day.

We grew up listening to her stories. We heard a lot of them, and sometimes they were our bedtime stories: her adventures with her best friend, Kentshereve; the bear that kept them captive when they were camping; the cabin with the magazine-page wallpaper; Aunt Tiny up on the roof; Uncle John’s pet mountain lion—we heard them all more than once. They were stories from her life and many would find their way into the stories that she later wrote and published.

When I was around six, while exploring a closet, I discovered a typewriter case. Inside was a folder with “A Peaceable Kingdom” written on the front. It was a story about two little girls selling musical vanity boxes all around El Paso. It was the first thing I ever read that wasn’t a children’s book. It was then that I realized my mom wasn’t just typing letters, she was writing stories. She explained to me how, a few years before, she had been published in magazines. She showed me copies of them and let me read them. After that, I often pestered her to let me read what she was working on, to which she would say, “When I’m finished.”

It would be another seven or eight years before she started finishing things enough to let me read them. By this time, she had two more sons (my brothers, David and Dan), was divorced from her third husband (our Dad, Buddy Berlin), had moved to Berkeley, and was struggling to make ends meet as a teacher at a small private high school. Amid the chaos (or because of it), she wrote more than ever. Most nights, after dinner and our favorite TV show, she would park herself at the kitchen table with a glass of bourbon and start writing, often continuing late into the night. She usually scribbled longhand with a ballpoint pen into spiral notebooks, though occasionally we would be awakened by the sound of her typewriter, often drowned out by her favorite song of the moment being played over and over on the stereo.

The first stories she finished around this time were ones she had started in New York and Albuquerque in the early sixties. These soon gave way to more personal stories born out of bad situations and personal tragedies, resulting from her worsening problem with alcohol. After losing her teaching job, she took on a series of different jobs (cleaning woman, telephone operator, hospital ward clerk) that would provide rich source material for new stories, as would time spent in drunk tanks and detox wards. Despite any setbacks, she continued to write and soon began to get published again.

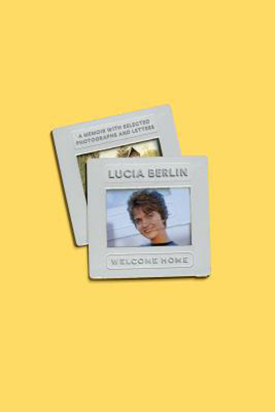

Years later, the last thing she had me read was an early draft of Welcome Home, a series of remembrances of the places she had called home. She had originally intended it to be simple sketches of the places themselves, with no characters or dialogue. These were the stories from her childhood that we had heard when we were kids but now in sequence and no longer masquerading as fiction. Unfortunately, time ran out and the last version of the manuscript ends in 1965, the last sentence unfinished.

During her life, Lucia wrote hundreds, if not thousands, of letters. Included here are some of our favorites from the same time frame as Welcome Home. Most of them are letters written to her good friends Ed Dorn and Helene Dorn between 1959 and 1965. It was a time of drama, growth, and upheaval, and the letters offer a fascinating look into the mind of a young mother and aspiring writer in the throes of self-discovery.

We give you Welcome Home; stories, letters, and photographs from the first twenty-nine years in the life of a unique American voice.

—Jeff Berlin, May 2018

1959 [September] Little Falls, New York

Dorns

501 Camino Sin Nombre

Santa Fe, New Mexico

Dear Dorns,

Do you know that as we turned onto the road to Race’s house we had driven exactly 2,000 miles and we were 20 minutes late—isn’t that fantastic—and now I understand it—it is the EAST—where everyone paints their barns on April 2 and mulches their trees on Sept 12 and there is order. Pope said something in a poem about the order in the chaos of nature or vice versa—I am gassed by the richness, TANGLED and matted opulence of the damned nature here—the bloody voluptuousness of rain and grass and snowballs, cosmos, jacko-lantern, sweet peas, pachysandra, and the order of the restraint people assume in the midst of it. It’s too much—and the bloody wasteland in Albuquerque—where people can’t take any strength or life from the earth so they give all of theirs up.

Trip was too much. Jeff was fine, Mark delighted, especially by Indianapolis. Once we had lunch under an ombú tree across from the copper colored sorghum by a watering hole.

The most magnificent thing I ever saw in my life was the MISSISSIPPI at Alton. I felt PATRIOTIC—imagine the settlers and pioneers.

We were efficient until St. Louis (never got a ruddy road map), where we got mixed up and almost made it to Mattoon— we drove all around up there—then later at about 2 A.M. I missed the Ohio through-way and this is the thing about the East—you can’t change your mind—you can’t screw up, you can’t stop.

NO STOPPING

At least in Missouri there were nice signs on one-way streets on the other side thru the rearview mirror that said

TURN BACK NOW

YOU ARE GOING IN THE WRONG DIRECTION

Anyway, I missed the through-way so we ended up in Cleveland where I got lost in almost dawn on streets above the FACTORIES—brick and fog and smoke and lights. Watch out. Wow.

And you know after going up there so we could drive by Lake Erie—the road was about 50 miles from the lake. We had a glimpse of it, at dawn, from Euclid Ave. in Cleveland.

We got to Race’s house on Sunday afternoon. This is the thing I would so love to express, my awe, my complete incomprehension of a real house where birches grow that were planted when each child was born with attics and cellars and summerhouses and all the people in the town have known everyone all their lives and all their relatives and they see each other all the time and like it and speak of birth and death with this fantastic War and Peace acceptance. Aunt Fan, showing us her (lovely) house—took us into the study—a real New England paneled study and said “We don’t use it much, except for funerals, to put the coats in.”

This is the thing I would so love to express, my awe, my complete incomprehension of a real house where birches grow that were planted when each child was born with attics and cellars and summerhouses and all the people in the town have known everyone all their lives

How lovely it was that Race brought me home—that “Sandy” came home. We are having a vacation and a rest and a honeymoon. Walk down Main St. and through these crazy flowers and grass all over—look thru boxes in the attic—with books and photos and poems by Race and have dinner in dining room with flowers and candles and butter plates and Mark picked corn from a corn field and washed it and ate it. (He is out of his HEAD!) Went to see cousin Andy and his wife Esther and Dorns, these people are TOO much— they work so hard and so easily and mulch (I love that word) and sow and reap and can and prune and graft and darn and bake and plant all their food and everything is so cyclical and ORDERED and NICE—they are all nice—with this crazy wit and an INTEREST in things, everything, and a joy from the views they see every day. I am meeting everyone. They take me in. I don’t mean they approve or accept or like me, altho they do, I think, but they take me into their War and Peace scene, to their cradles in the attic, and Jeff sleeping in Grandma Proctor’s crib that was Bobby’s crib too and it’s so nice and terrifying. I’ve never known a family.

I keep thinking of the last family reunion my family had, the children of my grandfather in El Paso and of Mamie, his wife, with big tears in her eyes as she held his coffee cup by the sides while he sat down so he could quick grab it by the handle and drink it down boiling.

That reunion was on Christmas and aside from being a house full of about 30 people there were these things happening. Most of all everyone there was wishing for my aunt to die. She and my uncle had been so bloody happy and in love and fine, all their life, but then she got very sick—really in agony—pain all the time. It was like a reverse Dorian Grey how her body began to destroy her with self-pity and fear and how she began to destroy everyone else. That Christmas Dr. Holt was there, who somehow illegally kept my aunt on cocaine and himself in terrible remorse and horror. My uncle who loved her and watched her and cried at night. Her children who hated her for making my uncle’s life so horrible. Her mother, who prayed, was crazy, and who my aunt wouldn’t let out of her room not even to eat, only twice a day to go to the bathroom. I was there and it was 2 weeks before my divorce was final and my parents were leaving in 3 weeks. Rex Kipp was there and he is a rich rancher and he and my uncle are best friends. A few days before, he and my uncle had split in a plane and everybody thought they had just gone to get drunk but I found out later they had been preparing for a Santa Claus thing in Mexico where during the night they went to this poor village and put seed and beans and meal and toys and clothes at all the doors. Which is a pretty repulsive Texan thing to do but not really if you think of two drunk millionaires putting around in a plane trying like hell to think of something nice to do, anything nice to do, with their money on Christmas.

Anyway, on Christmas Eve it was cold and there were several things going on—two factions—the drunk ones giving each other deep freezers and TV sets and telling jokes and the religious ones singing the Lord’s Prayer and some people cooking hams and turkeys. Poker games and people riding up on new Palominos and everybody had some personal scene— awful violent Faulkner scene going—aside from Christmas Eve, but it was Christmas Eve and my aunt said, “You want me to die, OK, I will,” and climbed onto a roof with only a bathrobe on and lay down and it snowed, in El Paso.

There is a crazy thing about my family. If you’re going thru a room and meet anyone going thru or sitting, you stop and you touch them, or you contact them—you affirm something—even if often it’s some bitter angry thing.

So I can’t understand these truly positive people—honest people. Here is the negative portion of my letter and this is what I meant, Edw., when I said I was afraid. I am afraid because I can’t make this scene, this nice, so really GOOD HONEST POSITIVE SCENE—where nobody weeps or screams or curses or hugs or fucks up or despairs or desires or kids themselves or dreams. Like the Newtons, truly so kind and they love Sandy (Race), very much—but when they saw him they said, “Why, hello Sanford!” But no weeping. When cousin Andy came back from the war half-dead, after horrible time, his father shook his hand. “Hello, Andrew.” Nobody is CORNY here.

And so corniness ultimately unimportant and superficial— the dependability and strength of love is here. Ah. But once when I was very little I dug Frost and “Stopping by Woods” and then I read “The Death of the Hired Man” and there is a line there that says (more or less) “Home is where, if you haven’t anywhere else to go, they have to take you in.”

I wish I had my damn typewriter—I want to write—which is crazy. I suddenly have 100s of things to write—but anyway the second day we were in Little Falls, in that lovely place, THE WELL RAN DRY! No water! First time in 60 years.

So we came to Hatch Lake—TO SHADYSIDE where SANDY GREW UP—A CRAZY LAKE and CRAZY (real) CABIN and we are camping, washing selves and clothes in the lake and Mark and Jeff delirious. Crayfish and snails and water snakes and squirrels and chickadees—we lie down in bed and see tons of trees and the sky and if you sit up against the pillow you look down on the lake. Right now we are at the dock and Jeff is throwing rocks and snails in the water. Race is reading (he has 100s of crazy books here), I am in a boat with a cat, and Heinz is tormenting us. Mark’s asleep in Grandma Proctor’s iron bed.

Last nite Aunt Moe, who lives next door, came to dinner with Race’s mother and father and Dana, his brother and Lee, Dana’s wife, and their children, and we had corn (you put the water on—then run and pick corn, quick dump it in, cover it with husks—cook for 3 min. and eat). We ate out on porch over lake on old chairs with oil cloth on table and it was nice and fun. Aunt Moe is as lovely a lady as I had imagined (she’s the box and paper lady). We had a good talk while we boiled water in crazy kettles and washed dishes and cut glass jelly bowls.

I’m getting seasick. Mark and Jeff are FAT and browning. I AM FAT—can’t button that blue dress I had in Santa Fe over me at all, in fact I am suddenly wholesome as hell—fat and no makeup (first time in 10 years) and tired from rowing and reaching across big old beds to make them.

Hey and the main reason I’m writing is that Race’s father, when we ran out of water, called Mr. Jay Murphy, who is a

DOUSER

who came in these crazy grey overalls with his alder stick and started stomping thru the woods and found where 3 veins of water met.

He gave me the stick and had me walk toward where the water was and I did and nothing happened. We did it again and he took one end of the Y and I took another—just barely holding it. He took my hand and as we got closer the end started to pull downwards—to be PULLED by the EARTH.

He said it didn’t matter what kind of a stick he used—that he could do it with wire, even, because it was the GIFT, his gift that mattered. “I don’t know why. I just know.”

Dr. Newton tested him by asking him to try it in places where he (Dr.) knew exactly where the vein was, and Mr. Murphy got it absolutely right. It was so damned far out, his hands so EASTERN and SO OLD.

Ee-ah, they say, instead of yeah or OK.

Aunt Moe has the gift of dousing too and I can see it—she has will. Didn’t we speak of this, Edw.? WILL, that is what people have here—somewhere it should relate to faith, like Melville’s, or to passion, somewhere it could, could be power—like Melville—because it is strength—but there is the order, the order of Melville’s “I and My Chimney.”

Now we are on the porch. I’m on a silly old chair by a pillow, with faded brown needlepoint that says:

LOOK UP AND NOT DOWN

LOOK FORWARD AND NOT BACK

LOOK OUT AND NOT IN

I keep beginning to end this illegible letter—but to end I always want to say something about leaving you and knowing you—we miss you. This is what’s left, like my uncle said, how we are friends.

Love, Lucia

P.S. Mark got in a rowboat all by himself—lugged the oars up and into the slot deal and rowed perfectly, except that boat was moored or anchored or whatever. He is radiant, beautiful.

My story came back from Kerouac. Said it was the wrong address—is it Rhode Island or Long Island?

Lucia Berlin (1936–2004) worked brilliantly but sporadically throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Her stories are inspired by her early childhood in various Western mining towns; her glamorous teenage years in Santiago, Chile; three failed marriages; a lifelong problem with alcoholism; her years spent in Berkeley, New Mexico, and Mexico City; and the various jobs she held to support her writing and her four sons. Sober and writing steadily by the 1990s, she took a visiting writer’s post at the University of Colorado in Boulder in 1994 and was soon promoted to associate professor. In 2001, in failing health, she moved to Southern California to be near her sons. She died in 2004 in Marina del Rey.

Lucia’s books include A Manual for Cleaning Women, Welcome Home, and Evening in Paradise.