Lucia Berlin was a Western writer, by which I do not mean a genre writer of cowboy tales like Zane Grey or the younger Elmore Leonard, but that her stories, with only a few exceptions, are situated west of the Great Plains or in Mexico. Berlin herself was born in Alaska and spent most of her childhood in Chile—a setting for several stories. The daughter of a mining man, she also lived in Montana, Idaho, Arizona, and Texas. El Paso is revisited time and again in her writing. The majority of her adult life was spent in New Mexico, Mexico, and the San Francisco Bay Area, chiefly Oakland.

The American West is on a different scale from the East. With Lucia Berlin we are very far away from the parlors of Boston and New York, and quite far away, too, from the fiction of manners, unless we are speaking of very bad manners. Landscape rules in the West. The individual is diminished or obliterated, along with his or her personality and will:

It was cool and smelled like the ocean. A few times the fog lifted and we saw stars. The best part was when the huge Japanese ships filled with cars came up the estuary. Like moving skyscrapers, all lit up. Ghost ships gliding past not making a sound. The waves they made were so big they were silent, rolling, not splashing. There were never more than one or two figures on any of the decks. Men alone, smoking, looking out at the city with no expression at all.

The principal narrator in this story is a woman in early middle age who is having an intense and troubled affair with one of her son’s teenage friends. At this point, the two of them are trespassing on a sailing boat in the local marina, drinking, making love, and taking in the evening’s sights and sounds.

In “Here It Is Saturday,” the narrator is a young white male en route from the city to the county jail:

After a long climb you come upon a valley in the hills. The land used to be the summer estate of a millionaire called Spreckles. The fields around the county jail are like the grounds of a French castle. That day there were a hundred Japanese plum trees in bloom. Flowering quince. Later on there were fields of daffodils, then iris.

In front of the jail is a meadow where there is a herd of buffalo. About sixty buffalo. Already there were six new calves. For some reason all the sick buffalo in the U.S. get sent here. Veterinarians treat them and study them. You can tell when dudes on the bus are doing their first time because they all freak out. “Whoa! What the fuck! Do they feed us buffalo? . . .”

The prison and the women’s jail, the auto shop and the greenhouses. No people, no other houses, so it seems as if you’re suddenly in an ancient prairie lit by sunbeams in the mist. The Bluebird bus always frightens the buffalo even though it comes once a week. They break into a gallop, stampede off toward the green hills.

Both passages have an element of the surreal, reflecting what happens when man-made instances of gigantism or extreme displacement intrude on the natural landscape. And both suggest how distant Berlin’s work is from the conventions of contemporary fiction with its emphasis on the domestic. Her stories are radically undomesticated, in both character and subject matter. There is no equilibrium, only disarray; behavior, on the whole, is feral.

Her stories are radically undomesticated, in both character and subject matter. There is no equilibrium, only disarray; behavior, on the whole, is feral.

Berlin’s style is unadorned, often telegraphic, rough-hewn, as if it were modeled on speech, the intimate letter, and the journal. At its best, her writing has an uncommon transparency, so that we are almost wholly unaware of any authorial presence. Readers looking for resemblances to more familiar contemporary American fiction might well seize on Raymond Carver. At the most superficial level, the titles of their books have a similar poker-faced offhandedness that counterpoints the gravity and bleakness of their subject matter. Carver: Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? or Where I’m Calling From; Berlin: Where I Live Now or So Long. Their protagonists tend to be blue-collar, though Berlin’s are often better educated and more exotic, as well as being psychologically nearer the edge. Like Carver, Berlin spent most of her adult life working in menial jobs while raising a family and knows that world intimately. Drink figures prominently in both writers’ work. Both are Westerners who situate their stories in the West, though for Carver locale has nothing like the significance it has for Berlin. Both use a bare-boned, demotic prose. They are dark writers: character, truth, destiny, what have you are revealed through desperation and failure.

Carver is the more polished writer, however. His achievement lies in his facility with voice and in the novelty of an art given over to the lives of the ordinary and flawed, who are portrayed in handsomely carpentered stories and well-judged prose. He is part of an American Realist tradition that runs from Dreiser and Crane, the Hemingway of the Nick Adams stories, Steinbeck, Farrell, and Algren. Berlin is both inside and outside this tradition. She is a wilder writer than Carver, with a greater stylistic range and a wider repertoire of voice and subject matter. Carver’s stories haven’t the brutality of Berlin’s. Few stories do. But, in the end, for all his enormous skills, he is a mannered writer, one story very like the next.

The unevenness of Berlin’s stories is in the service, I think, of her larger project. One story can be almost slovenly in execution, while the next has the controlled grace of a writer like Mavis Gallant: Berlin is several writers, some raw, some cooked. But more often than not the delivery is stripped down and usually in the first person. Details of character and place are so vivid that the stories feel autobiographical, an impression reinforced by her habit of going back to the same places—Oakland, Mexico, Albuquerque, El Paso—and characters: mother; the husband who’s a junkie; the other who’s a jazz musician; the sister; the sister dying; the boy lover.

The literary model is Chekhov, but there are extra-literary models, too, including the extended jazz solo, with its surges, convolutions, and asides. But Berlin’s aim is Chekhov’s: “truth, unconditional and honest.” The writer must strive to be as objective as the chemist, as concealed as the puppeteer, to resist manipulating character and complicating situation for the designs of plot and resolution.

The story “Carmen” is characteristic of Berlin’s work. It begins in Albuquerque, continues in El Paso and Juarez, and returns to Albuquerque. The narrator, Mona, a pregnant American, is asked by her heroin-addict husband to travel to Juarez, via El Paso, which is on the Mexican border, to score some heroin.

It was still hot in El Paso. I walked across the sinking soft tarmac from the plane, smelling the dirt and sage I remembered from childhood. I told the cabdriver to take me to the bridge, but first to drive around the alligator pond.

“Alligators? Them old alligators died off years ago.”

Mona crosses the bridge into Juarez.

It was hard climbing the stairs to the fourth floor. I was big with the baby and my legs were swollen and sore. I caught my breath in sobs at each landing. My knees and hands were shaking. I knocked on the door of number 43. Mel opened it and I stumbled in.

“Hey, sweetheart, what’s happening?”

“Water, please.” I sat on a dirty vinyl sofa. He brought me a Diet Coke, wiped the top with his shirt, smiled. He was dirty, handsome, moved like a cheetah . . .

“Where is La Nacha?” The woman was never referred to just as Nacha. “The Nacha,” whatever that meant. She came in, dressed in a black man’s suit and a white shirt. She sat at a chair behind the desk. I couldn’t tell if she was a male transvestite or a woman trying to look like a man. She was dark, almost black, with a Mayan face, red-black lipstick and nail polish, dark glasses. Her hair was short, slick. She held a stubby hand out to Mel without looking at me. I handed him the money. I saw her count the money.

Mona has been instructed to put the heroin in a condom inside her vagina. Her husband, Noodles, also told her not to let Mel out of her sight, not even for a minute. But at one point Mona has to urinate and briefly leaves the room.

When I got back I remembered that I wasn’t supposed to leave Mel alone. He was smiling. He handed me the condom, rolled up into a ball.

“Here you go, precious, you have a good trip. Go on now, put it away, like a good girl.” I turned around and acted like I was shoving it inside myself but it was just inside my too- tight underpants. Outside, in the dark of the hall I moved it to my bra.

I took the steps slowly, like a drunk. It was dark, filthy. At the second landing I heard the door open downstairs, noises from the street. Two young boys ran up the stairs. “Fíjate no más!” One of them pinned me to the wall, the other got my purse. Nothing was in it but loose bills, makeup. Everything else was in a pocket inside my jacket. He hit me.

“Let’s fuck her,” the other one said. “How?

You need a dick four feet long.” “Turn her around, bato.”

Just as he hit me again a door opened and an old man came running down the stairs with a knife. The boys turned and ran back outside. “Are you well?” the man asked in English.

Mona flies back to Albuquerque and goes straight from the airport to the trailer where her husband has been waiting for her.

He sat on the edge of the bed. On the table his outfit was ready and waiting. “Let me see it.” I handed him the balloon. He opened the cupboard above the bed and put it on the tiny scale. He turned and slapped me hard across the face. He had never hit me before. I sat there, numb, next to him. “You left Mel alone with it. Didn’t you. Didn’t you.”

But Berlin’s range was wide. “Evening in Paradise,” for example, is a gorgeous story set in Puerta Vallarta during the filming of The Night of the Iguana, with some inspired bits of Ava Gardner in it. And then there are the Mother stories, which appear throughout Berlin’s collections, and often show the writer at her best. These revolve around a manipulative, alcoholic, rather sadistic character who manages at times to be quite endearing and droll in a Bette Davis, damn-the-torpedoes sort of way. You are not likely to forget Mother. And then the delicate love story “Romance” takes place in upper Manhattan and involves two fortyish professionals. It is told in such a different register that it might have been written by another author—the aforementioned Ms. Gallant, for example.

Yet the writer Lucia Berlin most puts me in mind of is Richard Yates, better known as a novelist, but also the author of two remarkable collections of short stories: Eleven Kinds of Loneliness and Liars in Love. Yates’s technique is a good deal more familiar, and his writing more polished, or cooked, than Berlin’s. He was an Easterner, a New Yorker and Bostonian, who found a New York trade publisher and some success early in his career. Like Berlin, however, he believed in the Chekhovian notion that a writer’s business is to describe a situation so thoroughly that the reader can no longer evade it. Both have stock characters who become bleakly familiar over the course of their work. Both write about alcoholism, not in the Cheever manner of cocktail-party drinking drifting out of hand toward hallucination and divorce, but the sort that ends up in psychiatric wards. And both writers are relentless, on occasion horribly so: when you are several paragraphs into a story you get a sinking, even sickening, feeling of recognition. But you read on. It is writing of a very high order and not always easy to take.

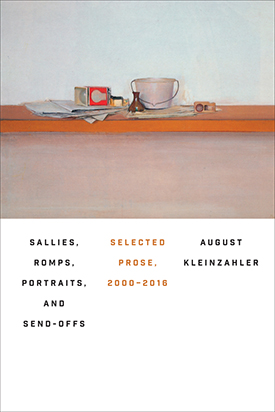

(Excerpted from Kleinzahler’s book, Sallies, Romps, Portraits, and Send-Offs)

August Kleinzahler was born in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1949. He is the author of several books of poems and a memoir, Cutty, One Rock. His collection The Strange Hours Travelers Keep was awarded the 2004 Griffin Poetry Prize, and Sleeping It Off in Rapid City won the 2008 National Book Critics Circle Award for poetry. That same year he received a Lannan Literary Award. He lives in San Francisco.

Lucia Berlin (1936–2004) worked brilliantly but sporadically throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Her stories are inspired by her early childhood in various Western mining towns; her glamorous teenage years in Santiago, Chile; three failed marriages; a lifelong problem with alcoholism; her years spent in Berkeley, New Mexico, and Mexico City; and the various jobs she held to support her writing and her four sons. Sober and writing steadily by the 1990s, she took a visiting writer’s post at the University of Colorado in Boulder in 1994 and was soon promoted to associate professor. In 2001, in failing health, she moved to Southern California to be near her sons. She died in 2004 in Marina del Rey.

Lucia’s books include A Manual for Cleaning Women, Welcome Home, and Evening in Paradise.