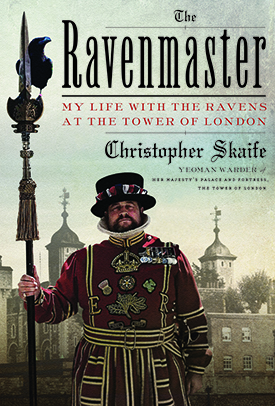

The ravens at the Tower of London are of mighty importance: rumor has it that if a raven from the Tower should ever leave, the city will fall. The title of Ravenmaster, therefore, is a serious title indeed, and after decades of serving the Queen, Yeoman Warder Christopher Skaife took on the added responsibility of caring for the infamous ravens. In The Ravenmaster, he lets us in on his life as he feeds his birds raw meat and biscuits soaked in blood, buys their food at Smithfield Market, and ensures that these unusual, misunderstood, and utterly brilliant corvids are healthy, happy, and ready to captivate the four million tourists who flock to the Tower every year. A rewarding, intimate, and inspiring partnership has developed between the ravens and their charismatic and charming human, the Ravenmaster, who shares the folklore, history, and superstitions surrounding the ravens and the Tower.

Now that you have a good sense of where we all live, you’ll probably want to know about our daily routine.

The Ravenmaster’s basic duties and responsibilities can be summarized thus:

1. Clean and prepare the ravens’ water bowls for the day

2. Clean their enclosures and remove any food they’ve discarded from the night before.

3. Check each raven closely for any health issues.

4. Feed the ravens; administer any medicines, such as worming tablets; monitor their food intake.

5. Release the ravens from the enclosures for the day.

6. Watch the ravens’ movements as they make their way to their territories, checking and recording any wing or leg damage.

7. Monitor the ravens throughout the day, ensuring the safety of both the ravens and the public and dealing with any issues arising.

8. Return the ravens safely to their enclosures at night.

9. Prepare food for the morning.

10. Final check before lights-out.

In theory that’s it. Sounds pretty easy, doesn’t it? In practice, though, it’s a little bit more complicated.

For simplicity’s sake, let’s begin at the beginning. I’m up and out onto Tower Green at the crack of dawn. My first call of the day, every day, is to check on Merlina, since she mostly likes to stay out at night, up on the rooftops. Merlina is the only raven who stays out at night. The other ravens all return to the enclosure on the south side of Tower Green. Merlina refuses to do so. Merlina treats the rooftops around Tower Green as a penthouse suite—a place to retreat and to contemplate the world. Once I can see her silhouette and I can hear her call, I make sure that the whole area around Tower Green is safe and clear from debris or anything that might harm the birds. And then I proceed to fill the water bowls.

Merlina

This might sound silly, but I love filling the water bowls. It’s one of the highlights of my day. I scrub and refill the bowls daily. There are plastic water bowls in the raven enclosures and six stone bowls dotted around the Tower’s Inner Ward where the ravens spend their days. I like the simple act of refilling the bowls, the sound of it, the smell of it, the clarity of the water. It’s a ritual for me. It’s my quiet time. This is when I get to clear my head and think about the day. They say that getting up and out early in the morning into the fresh air, no matter what the season, is good for your mental and physical health. All I can say is that I’ve been up and out early in all seasons every day for my entire working life, and so far so good.

There’s one water bowl which is up on the north side of Tower Green, by the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula. It’s believed that there may have been a place of worship there for over a thousand years, predating even the White Tower. Some even claim that this part of London is one of the nation’s ancient holy places, our own little central London Glastonbury or Stonehenge. And legend has it that there was once a spring of fresh water up at Tower Hill, the site of a sacred mound, and you get druids turning up these days in their costumes to celebrate the spring equinox, though I’ve never been tempted myself. According to Celtic legend, around here is also where the head of Brân the Blessed, the king of England in Welsh mythology, was buried. Brân means “raven” and he’s supposed to have been buried not far from the ravens’ current enclosures, which seems appropriate. (Bran is also of course the name of a character in the series of novels by George R. R. Martin, A Song of Ice and Fire, and its famous television adaptation, Game of Thrones. But more about Mr. Martin and the ravens later.)

I’ve heard it said that the name of London derives from Lugdunum, from the Celtic Lugdon, meaning town of ravens—mind you, I’ve also heard that the name comes from Llyn-don, Laindon, Karelundein, Caer Ludd, Lundunes, Lindonion, Lundene, Lundone, Ludenberk, Longidinium, and goodness knows what else. History and prehistory, legends, fables, and stories, they’re everywhere here. I sometimes think that the Tower is just a vast storehouse of the human imagination, and the ravens are its guardians.

History and prehistory, legends, fables, and stories, they’re everywhere here. I sometimes think that the Tower is just a vast storehouse of the human imagination, and the ravens are its guardians.

Anyway, I refill the bowl by St. Peter ad Vincula, where generations of Tower residents have been baptized—not in the ravens’ water bowl, I might add!—and married and, most famously, buried, including Sir Thomas More, Bishop Fisher, Queen Anne Boleyn, Queen Catherine Howard, and Lady Jane Grey, the uncrowned Queen of only nine days. Quite a few of them were also executed near the Chapel, or within the walls of the Tower—Anne Boleyn, of course, and Catherine Howard, Lady Jane Grey, Margaret Pole, Robert Devereux— so it’s certainly a church with a colorful history, though I’ve always thought the historian Thomas Macaulay was a bit down on the place in his History of England:

“In truth there is no sadder spot on the earth. . . . Death is there associated, not, as in Westminster Abbey and Saint Paul’s, with genius and virtue, with public veneration and imperishable renown; not, as in our humblest churches and churchyards, with everything that is most endearing in social and domestic charities; but with whatever is darkest in human nature and in human destiny, with the savage triumph of implacable enemies, with the inconstancy, the ingratitude, the cowardice of friends, with all the miseries of fallen greatness and of blighted fame.”

It’s not that bad! I rather like the chapel. It’s our parish church, after all, with a chaplain to guide and direct our spiritual lives and a fine choir and organists to lead the worship and uplift our spirits. Though, to be honest, I prefer to say my prayers outside, with brush and bucket in hand.

Fresh water sorted, brush and bucket safely stowed, every morning I then make my way to unlock the storeroom where I keep all of the food and equipment needed to aid me in looking after the ravens. I walk under the archway of the Bloody Tower onto the old cobbles of Water Lane (so-called because this is where the water of the Thames used to lap up against the walls of the Tower). Water Lane is part of Edward I’s Outer Ward, which was created during his big expansion program in the thirteenth century. It was reclaimed from the river by sinking thousands of beech piles into the Thames mud. I like having the storeroom here. I’ve always thought that back in the day Water Lane would have been full of wheelers and dealers, and duckers and divers coming in and out of the Tower and the old pubs that used to be here—the Stone Kitchen tavern was one, shut down by the Duke of Wellington long ago. The Tower has always been full of people, inside and out, and the Ravenmaster’s storeroom just sort of fits here, right in the thick of things, behind its own ancient black door, like an old apothecary’s shop.

Like all the other Yeoman Warders, on my key ring I keep a whistle to alert the others if there’s a problem. Plus I have a little skull and crossbones memento mori—you can’t work with ravens and not develop a bit of a taste for the macabre—and a small wooden raven totem pole, which I keep as a kind of talisman.

Now let me open up the storeroom and show you the Ravenmaster’s inner sanctum.

Christopher Skaife is Yeoman Warder (Beefeater) and Ravenmaster at the Tower of London. He has served in the British Army for twenty-four years, during which time he became a machine-gun specialist as well as an expert in survival and interrogation resistance. He has been featured on the History Channel, PBS, the BBC, Buzzfeed, Slate, and more. He lives at the Tower with his wife and, of course, the ravens.