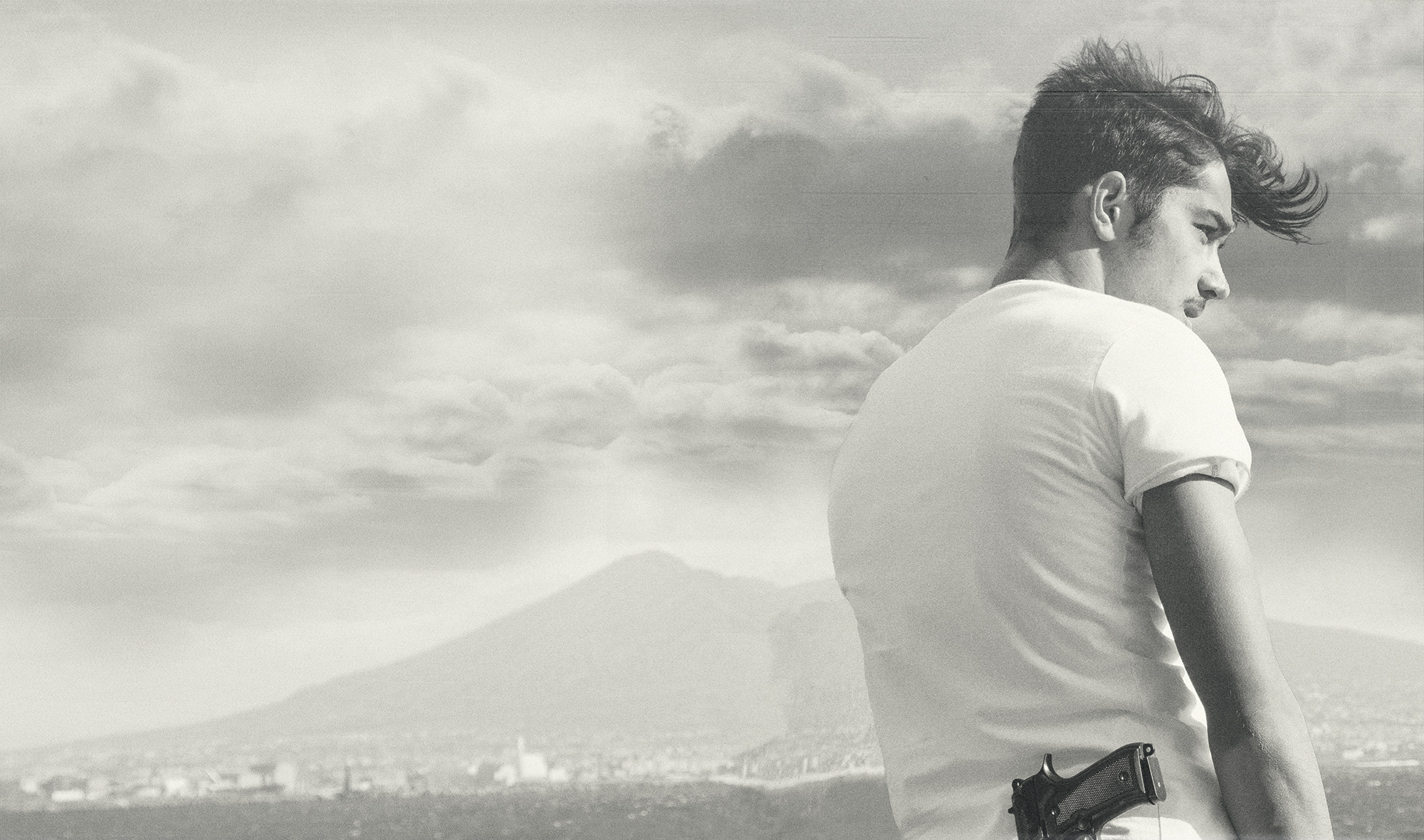

Nicolas Fiorillo is a brilliant and ambitious fifteen-year-old from the slums of Naples, eager to make his mark and to acquire power and the money that comes with it. With nine friends, he sets out to create a new paranza, or gang. Together they roam the streets on their motorscooters, learning how to break into the network of small-time hoodlums that controls drug-dealing and petty crime in the city. Slowly they begin to take control of the neighborhoods from enemy gangs while making alliances with failing old bosses. Nicolas’s strategic brilliance is prodigious, and his cohort rapidly rises and becomes enmeshed in a world of violence. With The Piranhas, Roberto Saviano returns to his home city and imagines the lurid glamour of Nicolas’s desire to rise to the top of Naples’s underworld. Elena Ferrante wrote: “With the openhearted rashness that belongs to every true writer, Saviano returns to tell the story of the fierce and grieving heart of Naples.”

Nicolas and Tucano found themselves all alone at Alvaro’s funeral. Besides the two of them, there was an old lady, who they learned was Alvaro’s mother, and a woman in a miniskirt, with the body of a twenty-year-old and, screwed onto the top of it, a face that bore the marks of all the johns she’d seen and serviced. Because there was no doubt about it, she was one of the Romanian whores that Copacabana used to send Alvaro, and from what they could tell, she was one of the fondest, given the fact that she was standing there next to his casket with a handkerchief in her hand.

“Giovan Battista, Giovan Battista,” the mother kept saying, and now she was leaning on the other woman, who might well have been a whore, but at least she’d had some genuine feeling for her unlucky son.

“Giovan Battista?” asked Tucano. “For real, what an absurd name, and what a shitty way to die.”

“ ’O White is a piece of shit,” said Nicolas. And for a second he tried to put together the image of Alvaro’s shattered brain with the last farewell of that woman with fine firm legs.

He was sorry about Alvaro, though he wasn’t exactly sure why. He didn’t even know if what he was experiencing was sorrow. That poor wretch had always taken them seriously, and that had to count for something. They didn’t even wait for the ceremony to be over; they just left the church, with other things already on their minds.

“How much money have you got on you?” asked Nicolas.

“Not much. But I’ve got three hundred euros or so at home.”

“Good, I got four hundred today myself. Let’s go buy a handgun.”

“Where are we going to buy this handgun?”

They’d come to a halt on the steps of the church, because that seemed like an important question to resolve; they looked each other in the eye. Nicolas wasn’t thinking of any particular pistol, he’d just done a little research on the Internet. What he needed was a gat to pull out when the time was right.

“Someone told me the Chinese sell plenty of old pistols,” he said.

“But excuse me, the Capelloni have more guns than they need, why don’t we try to get some from them?”

“No, we can’t. They’re System people, they’d get word to Copacabana in prison immediately. In no time he’d know everything, and he’d never give us the authorization, because it’s not our time yet. But the Chinese don’t talk to the System.”

“But who ever told them whether it’s time or not time? They took their time, and we need to take ours.”

Time, as Nicolas understood it, presented itself in only two forms, and there was no middle ground between them.

To Nicolas’s mind, it was a bullshit question to start with. The kind of question only someone who will never be in command would even think of asking. Time, as Nicolas understood it, presented itself in only two forms, and there was no middle ground between them. He always kept in mind an old story from the quarter, one of those stories that treads the fine line of truth, but is never called into question except to add details that reinforce the story’s moral. There was this kid, a guy with super-long feet. Two guys had come up to him and asked the time of day.

“It’s four thirty,” he’d replied.

“What time is it?” they’d asked him again, and he’d repeated the same answer as before.

“Is it your time to command?” they’d asked at last, before shooting him dead in the middle of the street. A story that made no sense, except to Nicolas, who’d immediately absorbed the lesson. Time. The instantaneous time of a claim to power, and the time smeared behind bars to let it grow. Now it was his turn to figure out how best to use his time, and that wasn’t the moment to lay claim to a power he hadn’t yet gathered.

Without a word, Nicolas headed for his Beverly and Tucano followed along, climbing on behind him, well aware he’d said too much. They went by Nicolas’s house to get the money, then they shot over to Chinatown, to Gianturco. A ghost quarter, that’s what Gianturco looks like, abandoned industrial sheds, a few little factories still chugging along, and warehouses for Chinese merchandise, adding red to a landscape that would otherwise smack only of grayness and anger etched on shattered walls and rusty roller blinds. Gianturco—which in Italian smacks of the east, of the color yellow, of fields of grain—is actually only the surname of a cabinet minister, Emanuele Gianturco, a minister in the newly united Italy, who championed civil rights as a guarantee of justice. A jurist long since deprived of his given name, who now stands for streets lined with abandoned warehouses, who now reeks of chemical refineries. It was once an industrial quarter, when there was still industry here. But this is how Nicolas had always seen it. He’d been here a few times as a child, when he still played on the soccer team of the Church of the Madonna del Salvatore. He’d started at age six with Briato’, one of them striker, the other goalie. But then it happened that during a game in the Under-12 championship among the parish churches, the referee had favored the Church of the Sacred Heart’s team, on which the sons of four city councilmen played. There’d been a penalty kick and Briato’ had managed to block it, but the referee had called for a retake because Nicolas had crossed the line before the whistle. It was true, he had, but being such a stickler over a parish church soccer match, after all, maybe they could have turned a blind eye, after all, they were just kids, after all, it was just a soccer match. At the second penalty kick, Briato’ had blocked the ball again, but this time, too, Nicolas had set foot across the line before the whistle, and the referee had called for the penalty kick to be repeated a third time. The third time, all eyes were on Nicolas, who didn’t move a muscle on this round. But the ball went into the net.

Briato’s father, the engineer Giacomo Capasso, with an impassive face and a slow stride, walked onto the field. With the most absolute calm he put his hand in his pocket, pulled out a switchblade knife, and gutted the soccer ball. With flat, undramatic gestures, with no visible sign of nervousness, he folded the blade shut, put the knife away in his pocket, and suddenly came face-to-face, nose-to-nose, with the referee, who was cursing, red-faced. Despite the fact that Capasso was shorter, he still dominated the situation. He spoke curtly and imperatively to the referee: “Tu si’ ’n omm’ ’e mmerd’—you’re a piece of shit—and that’s all anyone can say about you.” The torn ball on the ground was a green light for a general incursion onto the field, a full-fledged invasion with the full array of parents and children shouting in rage, with, here and there, a tear or two.

Nicolas and Fabio were taken by the hand by the engineer and led off the field. Nicolas felt safe, clinging to the hand that had held the knife minutes ago. He felt important, clutching that man’s hand.

Nicolas’s father, on the other hand, was tense, disgusted to have witnessed that scene in a crowd of children, on a little parish-church soccer field. But there was nothing he could say to the father of Fabio Briato’. He led his son over to the side of field, and that was that. When they got home, all he said to his wife was: “This boy’s not playing soccer anymore.” Nicolas went to bed without eating dinner: not because he was upset about quitting the team, as his parents mistakenly believed, but for the shame—lo scuorno—to have had the misfortune of a father who was unable to command respect, a man who counted for less than nothing.

Nicolas went to bed without eating dinner: not because he was upset about quitting the team, as his parents mistakenly believed, but for the shame—lo scuorno—to have had the misfortune of a father who was unable to command respect, a man who counted for less than nothing.

That marked the end of Briato’s and Nicolas’s soccer careers, as in the most classic story of friends and kindred spirits; they’d lost all desire to train. They went on kicking a soccer ball around, but without discipline, on the streets.

•••

Nicolas and Tucano parked the Beverly in front of a Chinese department store stuffed with merchandise.

The walls seemed to be on the verge of exploding with all the items packed inside. Shelves stacked high with lightbulbs, home power tools, stationery and school supplies, unmatched suits, children’s games, firecrackers, packets of tea and sun-faded boxes of cookies, and coffeemakers, diapers, picture frames, even an array of motor scooters—you could even buy the parts off them. Impossible to find any rationale for the way those objects had been arranged, save for a rigorous space-saving principle.

“Sti cinesi che hanno cumbinato, tutta Napoli s’hanno pigliato, poco ci manca e pure ’o pesone l’amm’ ’a pavà!” As he was singing Pino d’Amato’s song, Tucano rang the call bell that announced a new customer.

“Eh, still, that’s the truth,” said Nicolas, “sooner or later we really are going to have to pay rent to the Chinese to be able to live here.”

“But how do you know that they sell weapons in this shop?” They wandered up and down the aisles, past young Chinese men who were trying to squeeze hangers onto a rack that was already full to overflowing, or else climbing up on teetering ladders to stack up the umpteenth ream of paper.

“I was on a chat, and they told me that this is the place to come.”

No kidding?”

“Yeah, they sell lots of things here. We’re supposed to talk to Han.”

“If you ask me, these guys make more money than we do,” said Tucano.

“No doubt about it. People buy more lightbulbs than they do chunks of hash.”

“I’d only ever buy hash, forget about lightbulbs.”

“That’s because you’re a drug addict,” Nicolas replied with a laugh and squeezed Tucano’s shoulder. Then he spoke to a shop clerk: “Excuse me, is Han here?”

“Che vulite?” the shop clerk replied in perfect Neapolitan. What do you want? The two of them stood staring at the Chinese shop clerk and failed to notice that the anthill they’d walked into had frozen to a halt. Even the shop clerk standing poised on the ladder looked down on them, with a notebook in one hand.

“Che vulite?” the first Chinese clerk insisted, and Nicolas was about to repeat the question when a middle-aged woman whom they’d barely noticed behind the cash registers started screeching at them.

“Out, get out, go away, get out!” She hadn’t even bothered to get up from the perch where she had to sit all day taking in cash. From that distance, Nicolas and Tucano saw only a fat woman with teased-out hair and a flower-print shirt waving her arms at them to get back out the door they’d come in through.

“Eh, signora, what’s the matter?” Nicolas tried to understand, but the woman just went on shrieking, “Get out, both of you!” and the clerks who had at first seemed to be scattered throughout the big store were now encircling them.

“These fucking Chinese,” Tucano commented, dragging Nicolas along behind him. “So you see it was a bullshit mistake to get information in a chat room . . .”

“These fucking Chinese. Adda murì mammà, when we’re in charge, we’ll kick them out of here,” said his friend. “We’ll kick all them out of here. There are more Chinese than ants,” and as a form of moral redemption, he swung his hand at a good-luck cat that sat on a fake antique side table next to the entrance. The cat flew into the air and landed on the price scanner of one of the cash registers, cracking it, but the furious woman paid no attention, and kept on shouting in her loop of insults.

As they got on the Beverly, Tucano kept saying: “I knew it had to be bullshit,” and they drove off in the direction of Via Galileo Ferraris. Away from Chinatown. They’d accomplished nothing.

A short distance farther along, a motorcycle pulled up behind the scooter. The scooter sped up, and the motorbike revved its engine too, speeding up and staying close. Now they were really moving, determined to reach the stretch of road that empties out onto Piazza Garibaldi, where they could get lost in traffic. Swerving, darting between buses and cars, Vespas, pedestrians. Tucano kept craning his neck to check on the progress of whomever it might be that was following them, trying to gauge their intentions. The other guy was Chinese, impossible to say his age, a face he didn’t recognize, but he didn’t seem pissed off. At a certain point, he started beeping his horn and waving his arms, gesturing for them to pull over. They’d turned down Corso Arnaldo Lucci and come to a halt just before the Central Station, which was the boundary between Naples’s Chinatown and the casbah. Nicolas slammed the brakes on and the motorbike stopped right next to them. Both of them turned their eyes to the Chinese man’s delicate hands, but he gave no sign of pulling out a knife, or anything worse. Instead he reached over to shake hands and introduce himself: “I’m Han.”

“Ah, so you’re Han? Then why the fuck did mammeta kick us out of the store?” Tucano snapped.

“She’s not my mother.’

“Ah, well, if she’s not your mother she sure does look like it.”

“What are you looking for?” Han asked, jutting his chin out a little.

“You know what we’re looking for . . .”

“Then you need to come with me. Are you going to follow me or not?”

“Where are you taking us?”

“To a garage.”

“Sure.” They nodded and followed him. They were going back the way they’d come, but retracing your route in Naples can cost you hours in traffic.

The Chinese never dreamed of going all the way around the piazza; instead, the motor scooters took advantage of the gap for pedestrians between the concrete posts, and emerged in front of the Hotel Terminus. From there, back onto Via Galileo Ferraris and another left turn onto Via Gianturco.

Nicolas and Tucano realized they were going around in circles when they made their umpteenth left turn onto Via Brin. They’d left bright colors and commotion behind them. Via Brin looked like a ghost street. There were signs announcing warehouses for rent everywhere, and Han stopped outside one of these. He tilted his head, gesturing for them to follow him inside—better get the two motorbikes inside. Once they turned through the main gate, they found themselves in a courtyard lined with warehouses, some of them abandoned and tumbledown, others packed to the rafters with bric-a-brac and junk of all kinds. They followed Han into a garage that seemed no different from any of the others, except that it was neat as a pin. In particular, there were toys, copies of famous brands, more or less barefaced counterfeits. Shelves upon colorful shelves lined with all manner of wonderful products. Just a few years ago a place like this would have driven them out of their minds with delight.

“So we finally discovered that Santa Claus’s elves are Chinese.”

Han laughed aloud. He was identical to all the other sales clerks in the shop, perhaps he’d been one of the crew who surrounded them in the shop; maybe he’d laughed with gusto in the faces of those two when they were trying to find him.

“How much can you afford?”

They had more than they admitted, but they started out low: “Two hundred euros.”

“For two hundred euros I wouldn’t have even started my motorbike, I don’t have anything for that much.”

“Then I guess we’d better go,” said Tucano, ready to turn around and head out the exit.

“But if you guys can dig a little deeper, then I can offer you . . .”

He pushed aside boxes full of plastic machine guns, dolls, and plastic buckets and pails for the beach, and pulled out two pistols. “This is a Francotte, it’s a revolver.” He handed the one he’d identified to Nicolas.

“Mamma mia, it weighs a cuofano,” he exclaimed, astonished at how heavy it was.

And it was heavy. It was an ancient revolver, an 8mm; the only attractive thing about it was the handle, smooth, wooden, heavily worn, like a stone that had been polished by time underwater. All the rest of it— barrel, trigger, cylinder—was a leaden gray, dotted with stains that wouldn’t go away no matter how you buffed it, and it had that army surplus feel to it, or even worse, the feel of a gun used to shoot old Westerns, the kind that jam in two shots out of every three. But Nicolas didn’t care. He rubbed the handle and then started squeezing the barrel, while Han and Tucano continued bickering.

“This one works, eh, they brought it to me from Belgium. It’s a Belgian revolver. I can let you have it for a thousand euros . . .” Han was saying.

“Oh, to me it looks like a Colt,” said Tucano.

“Eh, it’s a fratocucino of the Colt.”

“Does this thing shoot?”

“Yes, but it only has three bullets.”

“I want to try it, otherwise I’m not buying it. And you’ve got to let me have it for six hundred.”

“No, but really, this gun, if I sell it to a collector, I’ll make five thousand euros. T’ ’o giuro,” Han swore in dialect.

Tucano tried out a few threats: “Sure you will, but then the collector, if you don’t sell it to him, it’s not like he’s going to come around and burn down your warehouse, or have you arrested, or set fire to your shop.”

Han kept his cool and turned to Nicolas to say: “Did you bring your sheepdog with you? Does he have to keep barking at me?”

Whereupon Tucano bared his teeth: “Keep it up and you’ll see if we’re all bark and no bite. Do you think we’re not hooked up with the System?”

“Then they’ll come for you.”

“Who are they going to come for?!”

With every exchange they drew a little closer, until Nicolas put an end to the discussion with a flat: “Oh, Tuca’.”

“No, seriously, now you’ve pissed me off, now get out of here, or else I’ll have to use this pistol on the two of you,” said Han. Now he had the knife by the handle, so to speak, but Nicolas had no interest in going any further, and dictated his conditions: “Oh, cine’, take it easy. We only want one, but it has to fire.”

“Go on, give it a try,” and Han put it in his hand. Nicolas couldn’t even get the drum to swing out so he could load it. He tried a second time, but it was no good: “How the fuck is this thing supposed to work?” and he handed it to Han, showing his disappointment.

Han took back the gun and fired off a shot, nonchalantly, without even bracing his arm. Nicolas and Tucano leaped into the air the way you do when you hear an unexpected detonation, and it’s not your conscious mind that’s reacting, only your nerves. They both felt ashamed of that uncontrolled reaction.

The bullet had taken the head clean off a doll on a high shelf, leaving the pink torso motionless.

The bullet had taken the head clean off a doll on a high shelf, leaving the pink torso motionless. Han just prayed they wouldn’t ask him to make the same shot again.

“What are we going to do,” asked Tucano, “with this hunk of junk?”

“For now this is the best we’ve got. Take it or leave it.”

“We’ll take it,” Nicolas concluded. “Still, since it’s a piece of crap, you can give it to us for five hundred euros, not a penny more.”

Roberto Saviano was born in 1979 and studied philosophy at the University of Naples. Gomorrah, his first book, has won many awards, including the prestigious 2006 Viareggio Literary Award, and was adapted into a play, a film, and a television series.

Antony Shugaar is a writer and translator. He is the author of Coast to Coast and I Lie for a Living and the coauthor, with Gianni Guadalupi, of Discovering America and Latitude Zero.