The characters in my novel Early Work think they know everything. In fact, they only know a few things, and most of it is half-remembered (at best) from books or films or articles they’ve seen or read. One of the things they (and their author!) would like to think they know about is art; Leslie, one of the book’s protagonists, is passionate enough about painting that she decides rather impulsively to get a master’s degree in art history in Montana. A number of scenes and themes in the book were inspired by paintings and artists I love, and the novel is dotted with (mis)informed discussions of various pieces as well. I thought it would be worth highlighting a few of them as a kind of visual appendix to the book, though for more in-depth and accurate analyses of these artists, the writing of non-fictional art historians is highly recommended.

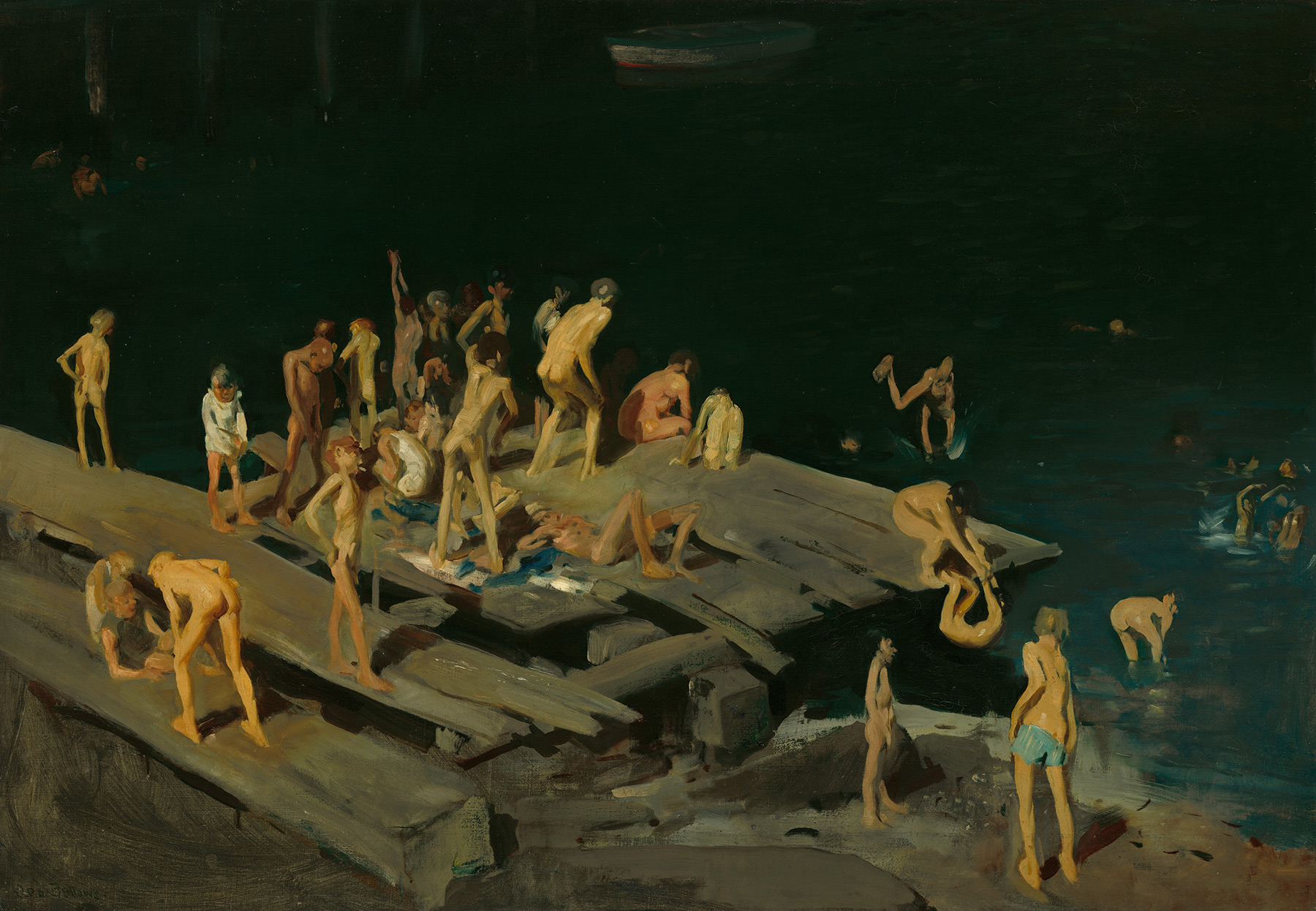

George Bellows, “Forty-two Kids,” 1907

I first saw this painting at the Met’s big Bellows show in 2012, and it has stayed with me ever since. In Roberta Smith’s deeply unimpressed review of the exhibition in the Times, she writes that “his painterly and caricatural ease collude so effectively that the figures read as cartoons.” But to my eye, the sketchy, almost wacky quality of the boys in the painting gives them a vibrancy that sends them hurtling and tussling forward into the 21st century. This is an example of Bellows’ vital, um, early work, a phase in which, like his like-minded literary forebear Stephen Crane, he brought a heightened, impressionistic approach to socially-conscious subject matter. (His decision to depict ethnically varied tenement dwellers drew hostile, anti-immigrant responses.)

Though the dock and swimming scenes in my novel are much less densely populated than that of the painting, I wanted to capture something of Bellows’ bustling energy in them, the childish glee one feels when presented with a precarious surface and some water to dive into. I especially like the strutting nonchalance of the naked fellow in the foreground on the left, who seems to be surveying the activity around him with a writer’s recording gaze.

Rogier van der Weyden, “Madonna and Child,” 1435-1438

Leslie’s girlfriend Katie is described as having “the helplessly expressive face of a Northern renaissance Madonna,” and paintings like this one are what I had in mind. Leslie is a (very non-observant) Catholic, which perhaps explains why she is continually drawn to the early European galleries in big art museums, content to soak in dozens of beatific Virgins and solemn crucifixions before remembering there’s another five hundred years of art to race through. My partner Laura and I saw this painting in the Prado, where we, too, were meandering more slowly than we realized through the grim and beautiful 14th and 15th centuries.

Winslow Homer, “The Gulf Stream,” 1899

This is one of my favorite paintings, which I brazenly hung on the wall of Leslie’s friend’s apartment just so she could notice it. (An actual friend’s house displayed a much goofier thrift store painting of a shark threatening some divers, so all I really did was upgrade his collection.) Like the Bellows, it comes close to illustration, especially in the depiction of the sharks, but the clashing tones and moods (the stoicism of the man, the Turnerish sublimity of the waves and sky, the Children’s Illustrated melodrama of the shipwreck scenario) give it a queasy jolt of the uncanny. The ship on the horizon was apparently added later to give the viewer a glimmer of hope, but to my eye, it’s moving in the opposite direction.

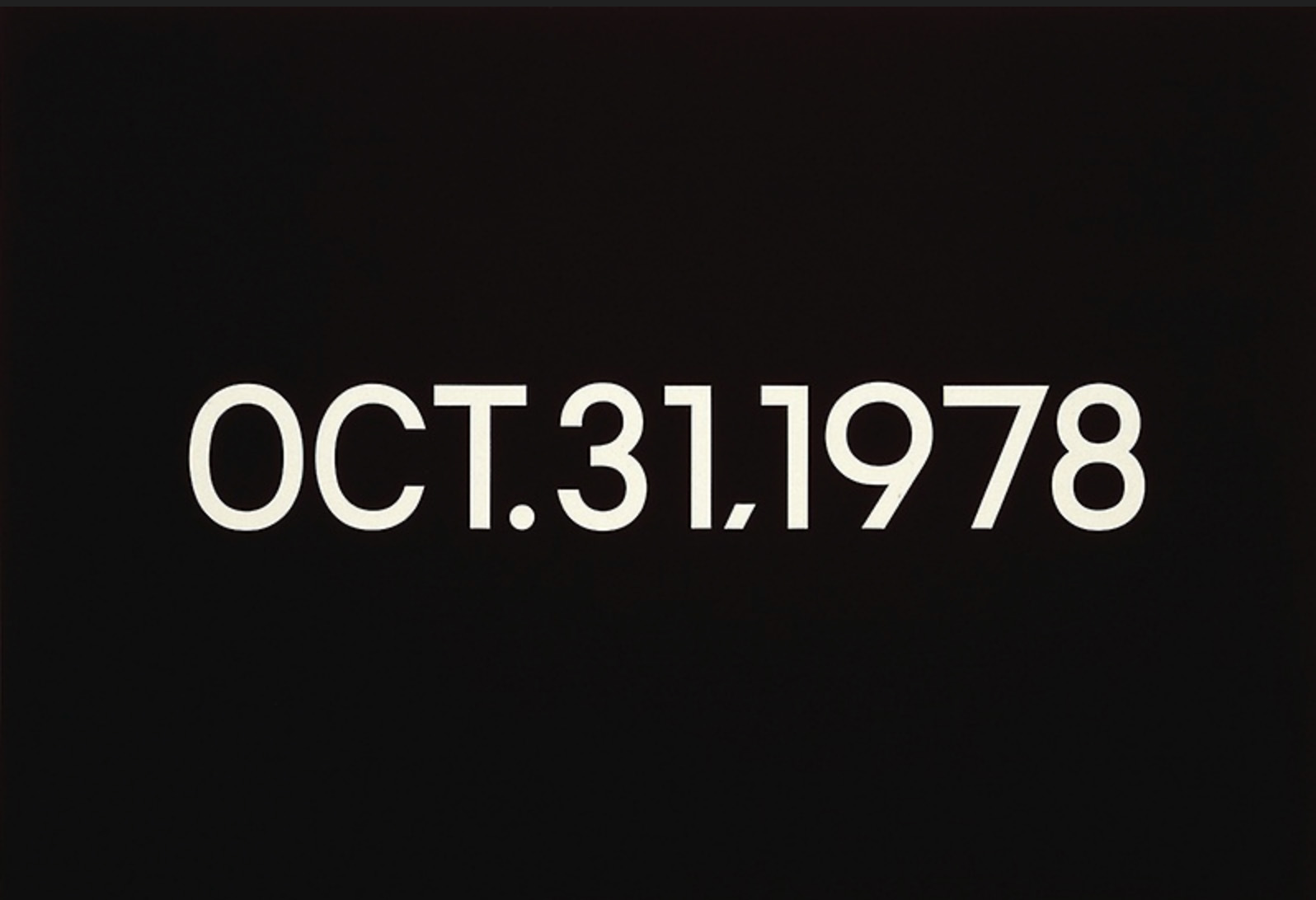

On Kawara, “October 31, 1978” (Today Series, “Tuesday”), 1978

Leslie sees this painting at a museum in the Hudson Valley, though its real, permanent home is the Chicago Institute of Art, which is probably where I saw it. Like the characters in the book, I’m both ambivalent about and strangely affected by this series of paintings, in which the artist painted the date in this style on a monochromatic background on over 2,000 individual days. Is it just a gimmick? Are we bringing more to the paintings than the artist is giving to the viewer? This particular painting, for example, was painted two days short of seven years before my birthday. I don’t think that should matter to me. But I think it does.

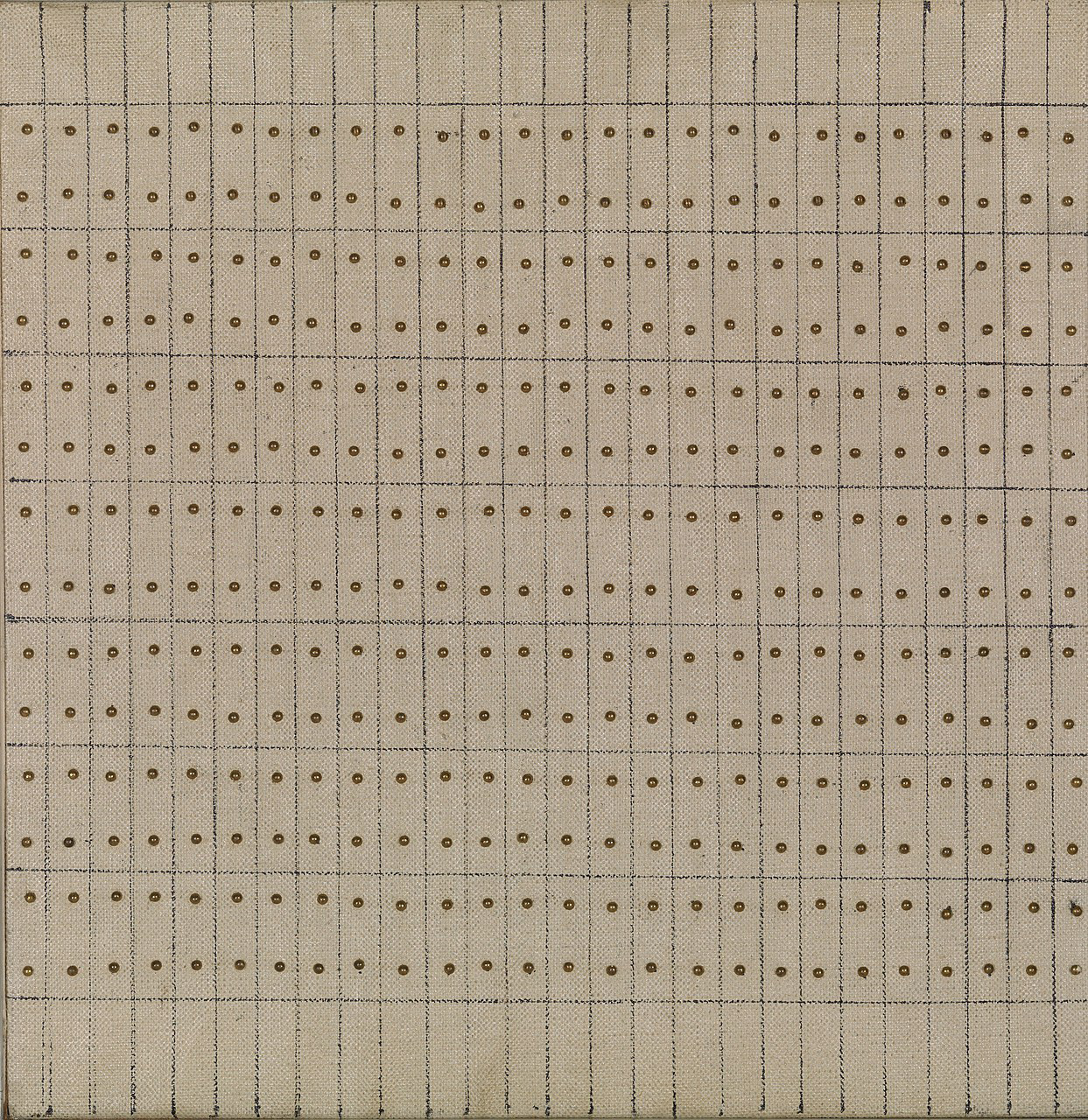

Agnes Martin, “Little Sister,” 1962

Like On Kawara’s work, Martin’s paintings inspire identification, despite, or maybe because of their willful refusal to court it. Knowing the narrative of her life helps—she famously shunned her early success in New York to work in the desert of New Mexico, where she painted through and around schizophrenic episodes—but the work, in its repetition and fragility, speaks for itself. Each painting seems to be an uncertain foray into the unknown, testing the possibilities presented by subtle gradations of line and color. This painting incorporates brass nails, making the contrast between the rigidity of the composition and the delicacy of her lines explicit. Though she isn’t mentioned directly in the novel, I imagine her work and life being a source of inspiration to the young artists in the book, who are trying to discover new ways of depicting the world.

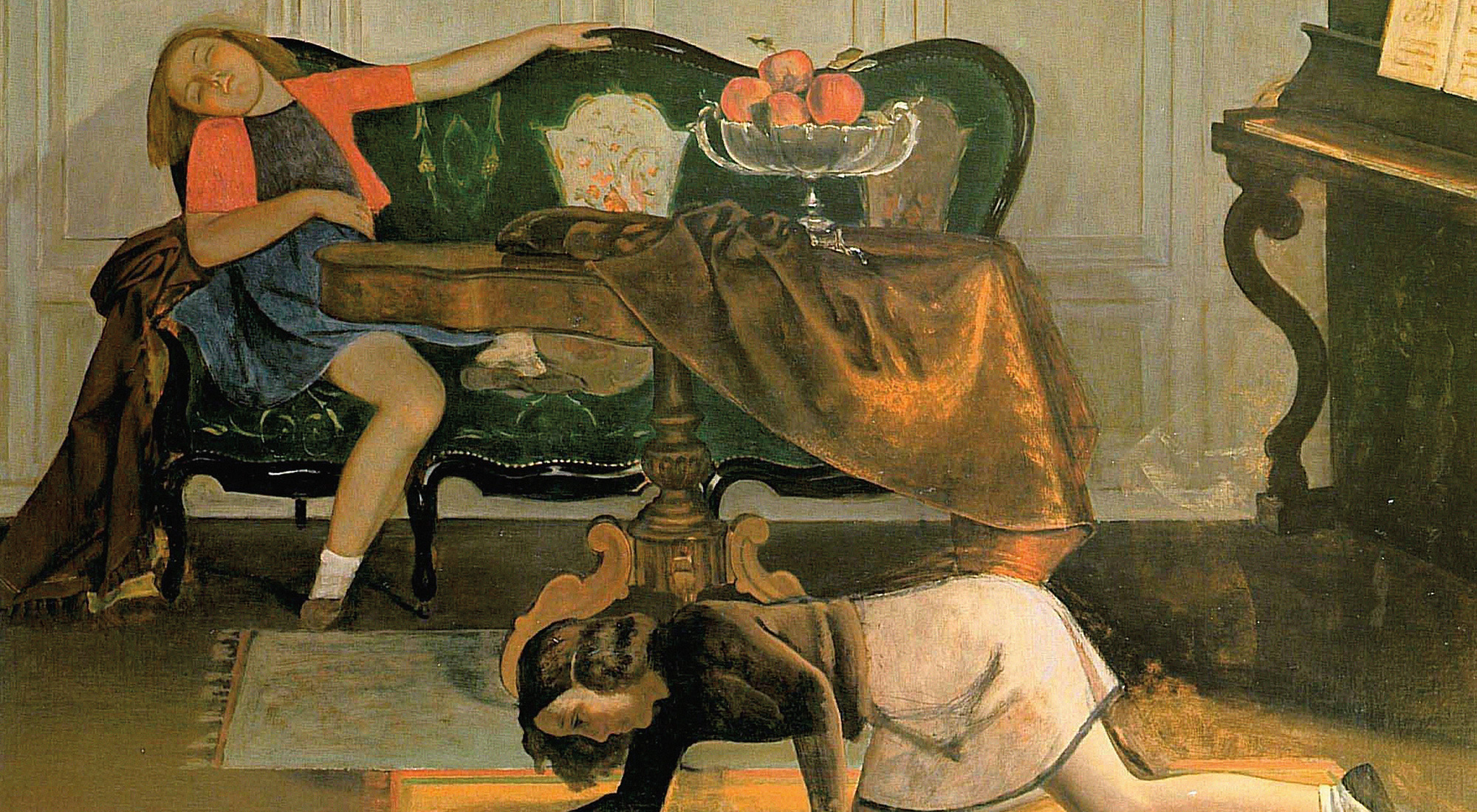

Pierre Bonnard, “Marthe and the dog, Black,” 1905

Bonnard is mentioned as one of the painters to whom Leslie can return again and again without getting tired of seeing his work. (She’s helped along in this opinion by an uncredited reading of Julian Barnes’ collection Keeping an Eye Open.) There’s something about Bonnard’s odd, ragged compositions, especially these interior domestic scenes, which seem to suggest secrets kept just out of reach. Is Marthe playing with the dog in this painting? Scolding it? Coming over to say hello? (His hopeful, uptilted head recalls Goya’s famous existential dog, though the stakes here seem quite a bit lower.) The proto-Rothko on the back wall edges everything towards a precipitous level of abstraction.

Most importantly, this painting stands in for the good dogs in my book, of which there are a number. The author would like to take this moment to acknowledge the significant contributions of their real world counterparts, who may be play-attacking each other across the lawn in front of me at this very moment.

Andrew Martin‘s stories have appeared in The Paris Review, Zyzzyva, and Tin House‘s Flash Fridays series, and his non-fiction has been published by The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, The Washington Post, and others. Early Work is his first novel.