In Champaign, Illinois, in the summer of 2011, in a closet in a bookstore consecrated to science fiction (the closet, that is, not the bookstore), I came upon a shelf of pocket paperbacks all attributed to one Barry N. Malzberg. I’m not sure what drew me to them. Perhaps that he had been prolific enough to fill a shelf (indeed, several) and yet lucky or unlucky enough to remain a total unknown to yours truly, despite my habitual haunting of just such closets . . .

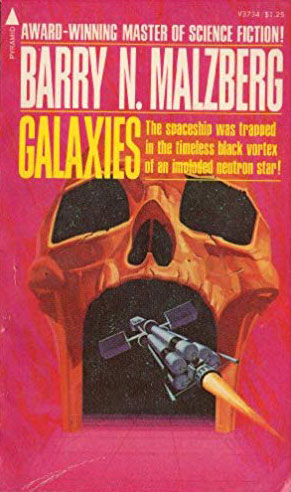

The first book I remember thumbing was his Galaxies (1975). The cover painting is of a spaceship zooming into the open mouth of a skull.

The opening lines, however, tell of a different quandary:

Galaxies by Barry N. Malzberg

To define terms at the outset, this will not be a novel so much as a series of notes toward one. Nevertheless pay attention, for it will cease to become a novel exactly at the point where it seems to be at last gathering force. Up until that time (which I will never tell), it will be as much of a novel as The Rammers of Arcturus or Slinking Slowly on the Slime Planet’s Sludge, titles which flank this to left and right with covers offering inducements—let me be honest about this—they will never fulfill.

Galaxies was my first love, and remains my favorite of Barry’s novels, but there are so many other titles that I have come to treasure that its position at the acme of my Malzbergian affections is virtually without meaning. I could as easily mention Revelations, Herovit’s World, Gather in the Hall of the Planets, or Underlay . . . or five or six others. The hell of it is that even minor Malzberg is often major, by virtue of his loony, gymnastic, tightrope-walking prose—which I’ve since learned he never even revised (!).

Point being, through a series of strange misadventures over the following years, I was lucky enough to become Mr. Malzberg’s occasional pen pal, and thereafter the editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux of another—perhaps madder—Malzberg fan, the great essayist J. D. Daniels, author of the acclaimed 2017 collection, The Correspondence. Daniels had already made waves among Malzbergians when he went on record about his love/hate relationship with Barry’s work at The Paris Review in 2013. Among the first things I told Daniels, when we introduced ourselves over the phone, was “I think we have a friend in common . . .”

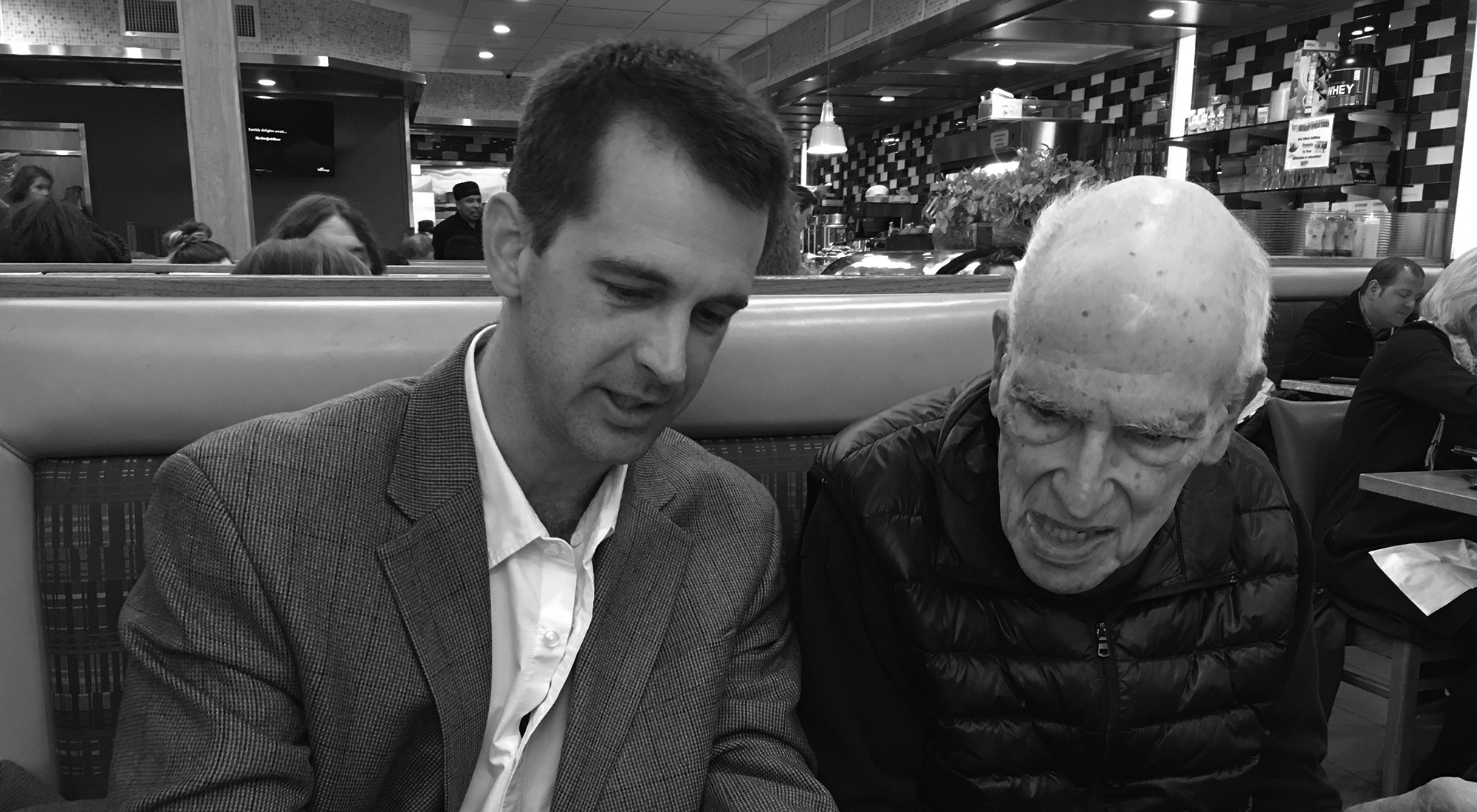

What could I do but bring these men together? First over email, and then over pastrami. Below are excerpts from their own singular correspondence.

—Jeremy M. Davies

• • •

Dear Barry Malzberg,

Before we begin, I want to tell you that I have read Screen, Falling Astronauts, Gather in the Hall of the Planets, Beyond Apollo, Overlay, Men Inside, Revelations (re-read until just loose pages falling out of its jacket), Herovit’s World, In the Enclosure, Tactics of Conquest, Destruction of the Temple, Sodom and Gomorrah Business (two copies, wore one out), Gamesman, Galaxies, Scop, Prose Bowl, Cross of Fire, and Remaking of Sigmund Freud, as well as a few volumes of your collected short fiction and essays.

Now I look back at my 2013 Paris Review article about your 1971–75 astronaut-psychosis novels. We know that a book is a gift, and that readers use books for whatever they need, without much connection to what its writer had in mind. And why not? I knew it at the time: “yet again I have projected my obsessions onto a relative innocent in order to deny and disown them.”

Given that my article was combative, showing respect through challenge, I thought you might like a second letter that is less disguised. More open gratitude.

To your “Say it and be done then: space is asepsis; it cancels differences, renders sexuality barren. That has been the secret of the power of science fiction for almost fifty years,” I say that space is difference, that space exists by virtue of differences between points. As in the expression: “Time is what keeps everything from happening all at once.” Space is what keeps everything from happening in an infinitely hot and dense dot. Maybe from a God’s-eye-view everything does happen at once. But none of us is God.

I don’t know what to say about your apparent implication that sex is “sepsis.”

Your devoted reader,

John Daniels

• • •

Dear John,

To begin at the beginning: I had no animosity toward your essay. It poleaxed me that someone so obviously intelligent, gifted, perceptive, in fact brilliant was so engaged (and so infuriated) by the collected works. “Hey, man,” I wanted to write: “You think that you as a reader regarded this stuff as an affliction? Try writing those novels.” But I could not unearth a contact address and, very much like your authorial persona for The Paris Review, I had to write that response in my head.

“You think that you as a reader regarded this stuff as an affliction? Try writing those novels.”

As I wrote my friend Jack M. Dann at the time, “What this brilliant and wracked essay really can find in compression is: ‘How can this wretched penny-a-word hack Malzberg with his (largely so constituted) corpus of paperback originals get so deeply into me, who writes for The Paris Review and is fiercely dedicated to quality lit?’” You could not answer that to your satisfaction. Rest assured that I have had similar problems with (as a stream-of-consciousness sampling) Randall Garrett, Tom Godwin and “The Cold Equations.” “We become what we behold,” I wrote almost forty years ago for The Engines of the Night, “and cannot tell the difference.”

I take your letter as one of apology, but no apology is remotely necessary. I think we should meet; I have already written Jeremy Davies suggesting that he find a lunch table in his neighborhood.

Saw your byline in Esquire article a few months ago and raised a fist like Carlos on the 1968 Olympic stand. “One for us,” I thought, “our letter to the world.”

Regards,

Barry N. Malzberg

• • •

Dear Barry (if I may),

I’m looking forward to our lunch at [redacted] on Wednesday.

I will try not to bring my entire BNM library for you to sign. Maybe only Falling Astronauts, Beyond Apollo, Revelations, Destruction of the Temple, Sodom and Gomorrah, and Galaxies, which I consider to be chapters of one long book you wrote from 1971–75.

You say: “We become what we behold, and cannot tell the difference.”

I say it a different way: “Monkey see, monkey do. So: what does monkey see?”

I’ll see you Wednesday.

Yours,

John

• • •

Dear John,

Hot damn, you were the guy I would think about in Syracuse in 1964 after another god-damned rejection from the god-damned Hudson Review (whose founder and editor Fred Morgan was one of the forty attendees at the First World SF Convention I learned less than a year ago): “Somewhere there is someone who wholly understands what I am trying to do and if indeed such a person exists he might help explain me to the world.” I look forward to meeting you.

Barry

• • •

Dear Barry,

You wrote: “Somewhere there is someone who wholly understands what I am trying to do and if indeed such a person exists he might help explain me to the world.”

This is what I understand: President Kennedy’s assassination (Whitman’s Lincoln-Captain’s death) was a national parricide, slaying a king-father who might have managed an engulfing-devouring-demos-horde, instead leaving a series of fatherless protagonists (male and female alike) to play hyper-masculinized roles as if self-fathering, attempting to protect themselves from that devouring Jocasta-Venus-Norma Bates by auto-castrating, by cutting ties to their mother-ships—by “containing Isis,” where “Isis” is, variously, Durga, Venus, Gaea, Rhea, Astarte, Ishtar, and Kali Ma, who rules the world.

But, as Haruki Murakami wrote in 1Q84, anyone who doesn’t understand this without an explanation isn’t going to understand it with an explanation—especially not an “explanation” as convoluted as that! Here’s the way I wrote it for Esquire.

“The president of the United States! It is an open question as to which is more pernicious: the wish to command or the wish to obey. Where there is no vision, the people perish. But the people will perish anyway.

“We know what we want. First we want to make a president or a king-in-the-woods, a godfather or a father-god. Then we want to kill our god.

“We want to kill the great white god under the sea, as in Moby Dick, as in Jaws, and we want him to rise from the dead so we can kill him again, as in Jaws 2, Jaws 3-D, and Jaws: The Revenge.

“Most of all, we don’t want to know that the him we kill is really her: a white whale disguising a black hole.”

See you tomorrow.

—John

• • •

A Foreign Edition of The Destruction of the Temple by Barry Malzberg

Dear John,

Yes, that is right as far as it goes but in “Death to the Keeper” (novelette F^SF 8/68) although barely aware, just a muffin of a writer when in March of ‘65 I wrote the play from which the novelette was extracted, there was another aspect . . . “parricide” of course but also envy, envy at the perfect god (lower case) who would retain his godhood, maybe even make the capital G by being martyred. George Stone, washed-up actor, knew that the only way to “purge national guilt” was to reenact the assassination with himself as the surrogate slaughter object but then he got in over his head, coming to understand too late that to kill JFK was to be JFK, not an actor playing the role but the real stuff. Then Jack Ruby took out Oswald and as Mailer wrote “It was at that moment, watching the murder on live television, that the nation went insane. And knowing that it was insane went over the edge forever.” Man, he wrote that fifty years ago. Trump was not even a mote in his eye.

Barry

• • •

Dear Barry,

I had so much fun at [redacted] with you and Jeremy—talking about [Stanley] Elkin, Ursula LeGuin, Cornell Woolrich, Mickey Spillane, Colin Wilson, Strindberg, Roth, Mailer, Malamud, Tiptree a.k.a. Sheldon, Westlake, Harlan Ellison, John Campbell, Aldiss, Moorcock, Philip K. Dick, Oates, Pohl, Disch, Algis Budrys, Clarke, Heinlein, Nabokov, Asimov, Vonnegut, Norman Spinrad, Brunner, John Dos Passos, Zadie Smith, Alfred Bester, DeLillo, Ballard, Delany, Arlene Heyman, Piers Anthony, [Robert] Sheckley, Boris Vian, and [Robert] Silverberg.

To say nothing of your theory about Bruckner’s scherzo, which I guess I’ll never hear the same way again.

I want to tell you that Mailer did once write what he, at least, considered to be “science fiction,” and he thought enough of the story (“The Last Night”) to close his collection Cannibals and Christians with it. I’m close enough to touch my copy. I keep the fiction alpha by surname: Doris Lessing, Ted Lewis, Clarice Lispector, Lovecraft, Mailer, Clarence Major, Malaparte, Malzberg, Mann, Olivia Manning, Hilary Mantel, D. Keith Mano—

Can you tell me more about your upcoming essay collection?

I’m looking forward to our next lunch. And to your next letter.

Yours,

John D.

• • •

Dear John,

Mailer apparently started a science fiction novel at nine or ten and it was printed somewhere, one of the posthumous works. “The Last Night” is defiantly science fiction. So is “The Man Who Studied Yoga,” which reads as if written by a humorless [Robert] Sheckley. (It’s kind of an alternate version of “Warm,” June of ‘53).

To have FSG print our correspondence would, as I wrote Jeremy last night, let me in through the back door. That was Beyond Apollo to me in 1971: “Son of a bitch, I got into Random House!” Of course, I had to sneak in by way of that tunnel running beneath the outhouse to the mailroom, but I managed. Redaction, as Jeremy offered? Except for [redacted], I wrote Jeremy, no redaction necessary. I truly do not give a damn. There is a certain joy to giving up, as I remember wisely saying on the phone to Dean Koontz in 1974 after spending an evening listening to a program on WBAI. Al Jolson imitators singing the repertoire, most of them miserably.

Write. Write, write. Not for FSG, not for posterity, but for its own simple sake.

Write. Write, write. Not for FSG, not for posterity, but for its own simple sake.

I know I am right about Bruckner, despite or perhaps because no musicologist or critic has to the best of my knowledge ever written this.

Kali Ma will rule the world

Barry

• • •

Dear Barry,

You do not have a proper sense of yourself. I don’t sneak in through back doors. When I walk through a door, it turns into the new front door.

You want [redacted] cut from your emails? We all have our secrets. I wouldn’t want anyone to know that I killed Olaf Palme for CIA on the day he was born in 1927 (when I was negative forty-seven years old) using a tachyonic anti-rifle and cryonic-hardened bullets hollow-tipped with toxic waste, as was standard for time-agents in the Twenties.

I’ve just listened to Barenboim conducting the scherzo from Bruckner Three. I don’t hear what you hear. I hear a one-legged man, dancing the best he can. Truth is a grace that flees from earnest effort, and Bruckner is earnest. He has his strong points, but light-heartedness is not among them; naturally, then, his scherzo must be odd. Now Gielen does number three, again. Now Wand does number four. (“Will you turn off that fucking ice-skating music,” my girlfriend says from the next room.)

As far as “write, write, write” goes: yes, of course, intrinsic rewards are the purest. But purity is an over-rated virtue.

I can always purify myself later, by going through the fire. I like the fire. It is bright and hot.

No, I won’t disdain extrinsic rewards. For example: our new friendship is something writing has brought into my life.

Yours,

John

• • •

Dear John,

Our observations are sometimes a projection of ourselves, other times the lens through which a tenuous reality passes. To me, Bruckner’s scherzos are the unleashing of the fury of a man who couldn’t get a date or a meaningful hearing until he was forty, and then just barely. To you, he is a one-legged man trying to dance. To which I respond, and then we can pass on to matters less Brucknerian, try the scherzo of the Symphony Null, the so-called “zero” in program books. Wild as Berlioz on a day trip in a cart overflowing with hallucinogens.

Your time-travel assassination story was one of the ’50s SF outliers. There’s Pohl’s first-person story of the expedition to kill Einstein in his cradle and leave the atom unsplit, and Pohl’s narrator after it has been done thinks of the gentle, saintly old man who had been that helpless baby. History reposes upon brutality whether or not it happens. It’s an allegation with which I used to toy now and then. I always liked Damon Knight’s “If something is true, it is true whether it happens or not.”

The scherzos (scherzi) of Bruckner 1 and 3 are almost indistinguishable. Self-plagiarism is not a crime; if it were, I would have had another life.

Barry

J. D. Daniels is the recipient of a 2016 Whiting Writers’ Award and The Paris Review’s 2013 Terry Southern Prize. His “Letter from Majorca” was selected for The Best American Essays 2013. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Correspondence is his debut book.

For nearly half a century, Barry N. Malzberg has been stretching the boundaries of the science fiction and fantasy genres to tell truly entertaining tales.