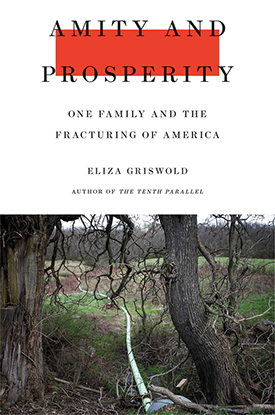

In Amity and Prosperity, prize-winning poet and journalist Eliza Griswold draws on seven years of reporting to tell the story of the energy industry’s impact on a small town at the edge of Appalachia, and one woman’s transformation from a struggling single parent to an unlikely activist. Stacey Haney is a local nurse working hard to raise two kids and keep up her small farm when the fracking boom comes to her hometown of Amity, Pennsylvania. Intrigued by reports of lucrative natural gas leases in her neighbors’ mailboxes, she strikes a deal with a Texas-based energy company. When mysterious sicknesses begin to afflict her children, she appeals to the company for help but is assured that nothing is wrong. Alarmed by her children’s illnesses, Haney joins with neighbors and a committed husband-and-wife legal team to investigate what’s really in the water and air. Here, Griswold discusses her book, as well as her experience of immersing herself in the world of the story for seven years, with author Alex Kotlowitz.

Alex Kotlowitz: It’s such an honor and privilege to be here with Eliza Griswold, whose book Amity and Prosperity is due out next week. It’s an absolutely essential read. For me, the thing I love about it is it just underscores the bigness of the small story. Eliza’s spent a number of years with one family in particular and their neighbors in rural western Pennsylvania, as they reckon with the deleterious effects of fracking. But it’s really much more than a book about fracking. It really is more about what holds us together and keeps us apart in this country and I want to talk some about that. This is really Trump’s haven. But, the place to begin would be to have you, Eliza, read a short section from the book.

Eliza Griswold: Sure, I’d love to do that. I have to say, it’s like a dream come true sitting here with you, Alex. You were the first person I ever interviewed. I think I was in high school when I came to the Macarthur Foundation when you were there and sat across from you and I cannot even remember what I asked you. I just remember being terrified and feeling so dumb and, in retrospect, to think that you would give the time to a high school student to be like, “Sure, come on in and talk to me about There Are No Children Here” is just a real honor.

I’m going to read to you a little bit about the boy who is at the center of this book and his name is Harley Haney and he was fourteen when the book began and this is about him in March of 2010.

“Down the hill, during that month of March 2010, Harley was ill. For much of his seventh-grade year he’d been waking up sick to his stomach, stricken with diarrhea. Because of his stomach pains and the canker sores that kept appearing in his mouth, he didn’t want to eat. To coax him, Stacey cooked his favorite foods, chicken and stuffed shells, grilled cheese. Still, he only picked at meals. Finally, he’d missed so much of seventh grade that she’d enrolled him in a homebound program. Once a week the teacher came to the house with his homework. Stacey tried everything she’d learned over twenty-three years of nursing to figure out what was wrong. They’d made trips to the Children’s Hospital in Pittsburgh and the ER at Washington Hospital, where she worked. Harley was tested for appendicitis, Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel syndrome, cat scratch fever (after one of the Haneys’ three cats, Cheyenne, scratched his lip), Rocky Mountain spotted fever, mononucleosis, swine flu. All came back negative.”

Kotlowitz: One of the things I love about this book is that it’s incredibly intimate and the center of this story is Harley’s family—his sister Paige and his mom Stacey, who’s a nurse and a single mom. So, I’m curious how you even found them and why they decided to tell their story and to tell it in this very public way.

Griswold: The book’s genesis actually dates back to Nigeria. Most of my work as a journalist before I wrote this book had been outside of the United States, primarily in Africa and Asia, Afghanistan, Iraq, and so when I was in Nigeria some years ago a bridge had collapsed in this tiny town and I had to get to the tiny town across a river. I was riding across an empty oil barrier—as you do, when you have to get across a river—and a couple of people had died in this terrible flooding. But it was two weeks after the bridge in Minneapolis, I-35 West, had collapsed, killing thirteen people, and there was something about that moment. I thought, “It’s time to go back to the United States to look at our collective poverty. What are the problems happening there that are underreported—because they’re not just happening around the rest of the world, they’re at home, too.”

That took me back to the United States where I wanted to write about public poverty. And I began thinking about crumbling bridges and infrastructure and I looked at where, statistically, there were the most crumbling bridges in America and it was southwestern Pennsylvania. So, I headed out there and started wearing a hard hat and bright flashing vests and standing on the highway with engineers who knew that I could not tell an I-beam from my fingernail.

One day I just headed out to a community meeting and all these questions of public poverty and how communities paid costs of private industry were circling around fracking. And, for the first time she ever spoke publicly, Stacey Haney stood up at the Morgantown West Virginia Airport and she told the story that was really the beginning of this mystery. She knew that she and her kids had benzene and toluene in their bodies. She knew that they had been exposed to arsenic. She had found that a quarter mile from their home there was a massive industrial waste pond, but that’s all she knew.

Afterwards, she was really nervous to speak out. She was really nervous because at the time she thought her water was contaminated and that the gas company who owned the pond was supplying her drinking water. And she was afraid that if she spoke out publicly they would retaliate and take the water away. So, when I approached her after this meeting it was with the understanding that I didn’t have to write something the next day for The New York Times. I was just going to hang out with her so that she and I could talk about her story. I think that was appealing. I think that made her feel safe, and that’s why she decided to talk to me.

Kotlowitz: One of the things for me that you do so beautifully in this book is that you see the journey that she takes. A little backstory: she lives in a farmhouse in rural Pennsylvania right near these two towns and up on the hill is where they are doing the fracking—an incredibly toxic process. They’ve got a huge retaining pond which it eventually becomes apparent is leaking and overflowing. But, as you’ve heard in that excerpt Eliza read, her son is facing all these medical issues and yet she’s getting a lot of pushback in the town because the thing about fracking is that it’s brought all this money into the community. And one of the things that’s so striking, whether intentional or not, is that it completely fractures this community, these people who were lifelong neighbors.

What really interests me in this area is how over the course of a century, the rural Americans who’ve lived here have paid the energy costs of urban Americans, beginning with coal.

Griswold: What really interests me in this area is how over the course of a century, the rural Americans who’ve lived here have paid the energy costs of urban Americans, beginning with coal. Prosperity, the nearby town, is a big coal mining area. So her family began in Prosperity and then moved to Amity and those two towns are just ten miles apart. Prosperity has all been undermined. Industrial coal mining has come underneath it and many of the farms of people who live there have lost their access to water. What happens is the coal company buys up a farm and they pay a lot of money. They pay more than you might pay for that farm, and lots of people love it—they call it the “long wall lottery,” because it’s a particular type of mining. It allows them to leave these farms behind. But some people don’t like it because they lose everything. So, you have this longstanding process concerning the cost that extractive industry is going to take from us. The reason that fracking promised to be different is that finally people were going to make substantial amounts of money from signing mineral leases. These are incredibly sophisticated people.

That’s one thing I really hope the book does—restore the sophistication and intelligence of rural Americans—because these guys know what they were signing and why. They saw these deals and said, “You know what? I need a new roof on my barn or I’m going to lose this farm entirely.” And so some of her neighbors, particularly larger landowners, made a lot of money, hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars, on this process when those who tended to be poorer and have smaller chunks of land from the beginning made less. So, this had definitely divided communities and turned neighbors against one another really for the first time in a very long time.

Kotlowitz: There’s a moment in the book during a deposition where the Haneys’ neighbor, John Voyles—who owns a horse farm and so he’s been equally impacted by it—talks about how he’s kept to himself all these years and says, “You know, it ain’t been working so well.”

Griswold: I think that’s one of the tensions that runs through this community. We often look at the impact of globalization in a war zone because instantly you have a conflict, you have international troops coming in, and you have journalists. We are part of the process of globalization. And with fracking you have the same thing. So, you have people who have chosen, really deliberately chosen, to live out of the way. People who really do prefer to keep to themselves. And suddenly they’re overrun not just by the forces of industry, but also by journalists like me who are coming to knock on their doors.

Kotlowitz: Right. One of the things that’s kind of interesting to me is there’s a lot of distrust towards government from these people. A lot of distrust towards outsiders. But one of the things that surprised me is, with the exception of Stacey and her neighbors, the people were very accepting and trusting of the natural gas company that came in. You think that’s simply because of the money that exchanged hands?

Griswold: Well, first of all, the gas company has many supporters in the area—and I write about them pretty substantially in the book. And the gas company brought in jobs as well as some support for local nonprofits. I didn’t understand before I wrote this book what farming regulation has meant to people living in this area. I think the impact of government regulation on small farms is much more profound than I had understood. And because of that, many people understand the federal government to be rapacious and against their interests, and corporate interests, at least, are paying something back and giving them something. So, that’s the complex calculation that I had trouble with—so many people at a distance say, “Well, can’t you just do adequate regulation? Isn’t adequate regulation going to fix the problem?” The word “regulation” is a bad word in lots of places, and I don’t think we understand that message significantly.

Kotlowitz: Part of what Stacey was up against was trying to get these regulators to come in and actually do their jobs. The company that’s doing the fracking is very deliberate about how they deal with the community. There’s a moment in the book that feels like a kind of metaphor for how they dealt with them. It’s early in the book when it’s clear that Harley has arsenic poisoning and they go to meet with some of the representatives of the natural gas company. And while they’re there, two things happen: one of the representatives suggests to Harley that maybe he got arsenic poisoning from woodwork classes in high school. The other thing is that there’s also a guy sitting there—and I can’t get it out of my mind—a guy sitting in the meeting with his feet up on the desk scrolling through his cell phone while Stacey and her son are there to talk about this metal poisoning that has become so critical that the local doctor now has begun testing everybody for metals.

Griswold: Yeah, that moment has shaped Harley’s life. When I first met Harley, he was sick. He still wanted to go to college and become a veterinarian, and by the end of the book, he’s given up on not just medical school, but also college. He had then wanted to go into the military, but because of his litany of illnesses, he didn’t think he’d be physically up to it. And he is now working on a suburban gas pipeline and living in his mom’s basement. So, Harley’s understanding of what has happened to him is that the world has turned against him and it’s definitely impacted who he is.

Harley’s understanding of what has happened to him is that the world has turned against him and it’s definitely impacted who he is.

Kotlowitz: It’s the arrogance of the gas company that really gets his ire up. I want to pull back for a moment. In your first book, The Tenth Parallel, which is just this beautiful exploration of the intersections of religion—in the opening chapter set in central Sudan, you’re meeting with a village chief there and his big concern is that soldiers from the North are going to come and take over his village because of the oil beneath his land. And you talk about this resource curse. Can you talk about that? Because it feels very relevant to this place in western Pennsylvania as well.

Griswold: Chief Nyol Paduot is warning that these soldiers are coming and, in fact, they do come. And they sweep these people off their land in order to claim the rights to the oil beneath. Since the 1990s, economists have looked at something we call the resource curse. Why is it that people who live on land richest in natural resources are some of the poorest? We typically look at it in the global South, and what we see is a pattern of weak governments. Basically, people and governments supporting lack of investment in education and other more productive, long-term investment in favor of cashing out with mineral resources. And this idea applies nowhere more in America than in Appalachia, where for centuries people have paid the cost of our energy and we don’t even know what that means. We don’t know what it means to live on top of a coal mine or a coal field, or what it means to have your kids subjected to all these industrial pressures. And to understand the tensions between rural and urban Americans—and I say that as an urban American—we really have to understand that rural people have paid for the rest of us to live our daily lives.

Kotlowitz: Reading your book—I don’t know if you ever read Harry Caudill’s Night Comes to the Cumberland—

Griswold: Yes! That’s one of my favorite books.

Kotlowitz: Yes, so there’s a book that came out in 1962 about Appalachia and about the raping of Appalachia because of the coal. There’s this line where Caudill writes, “We will continue to ignore them”—and he’s talking about those in Appalachia, those in the very community you wrote about—“at peril to ourselves and our posterity.” And I thought, my god, how prescient.

Griswold: Yep. Somebody was commenting today on the book and they said, “You know, clean air and pure water are not a Liberal issue, they’re not a Conservative issue, they’re a practical issue of common sense.” And we need to return to that because what’s happened with fracking in particular is that it’s become a political football where if you say fracking to a Liberal or Conservative person, you pretty much know what you’re going to get back. So, how can we find our shared values in the very things that we need in order to survive and for our kids to survive?

Kotlowitz: And I’m curious, did you sense why people in communities like Amity and Prosperity would vote for Trump?

Griswold: A thousand percent. I was writing this book so many years before Trump fever arrived in the area. There were many reasons, but one of the reasons is this historic disenfranchisement. And Trump came to Pittsburgh and said, “You guys are going to make so much more money off fracking.” And he was talking about people in New York—people in New York are going to be driving Cadillacs, you know? And he made this promise—that age-old promise—that wealth and prosperity were just around the corner, and what’s been keeping wealth and prosperity from you has been the federal government, and that he, as the new government, would get out of your way. And it was a fantasy. I mean, we can see in the Environmental Protection Agency under Scott Pruitt a level of human disregard that plays out in a very real and destructive way in the lives of rural Americans who are relying on the federal government to keep their air, their water, and their kids safe.

Kotlowitz: I think one of the things for me that was a little despairing about this book was that the federal government wasn’t involved as much as the state agencies here. The Department of Economic Protection had their budget slashed by a third in the years preceding this fracking year. How do we restore people’s faith in government, in this notion that government actually is there to protect the most vulnerable?

Griswold: That is the billion-dollar question, right? I mean, what really fails the people in this book is the government. John and Kendra Smith, the local lawyers involved in the case, who take on this massive industry, are remarkable human beings. Kendra is not a plaintiff lawyer. She is a corporate defense attorney for asbestos cases, exposure cases for the railroad. And she said to me many times, “A corporation will do what it does, but it’s a government failure here.” The government has a responsibility, both state and federal. So, how to even begin to address that? As journalists, we are often asked when we do long-term projects that look at trouble in America or abroad, “Well, what’s the solution here?” The first step to finding a solution is to understand the nature of the problem. And I hope it’s not a copout to say that that’s where the book begins. It is such a quiet story. It’s a daily tragedy befalling lots of Americans. And so, hopefully, by paying attention to that, we can begin to understand the larger nature.

Kotlowitz: I want to switch gears for a moment just as a fellow writer, and talk a little bit about process. You’re also a poet, and I’m curious how your poetry or your inclination to write poetry impacts your nonfiction writing if at all.

Griswold: I think what poetry and nonfiction or reporting have in common is they are rewarded for a keen sense of paying attention. Whether you’re paying attention to the exterior landscape or the interior landscape, there’s a honing of that skill of using the senses. Poetry is often what can’t go on a page because it’s just too uncertain. I have a book of poems coming out next year, and I often use the poems to explore space where I’m implicated in ways that make me uncomfortable. I am, like you, a nonfiction writer who is not afraid of the “I.” I’m not afraid of the vertical pronoun. But I don’t embrace it all the time because I really see myself as a witness to other people’s stories, and their sensibility is the first priority.

Kotlowitz: You are only in this book a little, but it’s in some ways purely for mechanical reasons. I mean, we don’t really learn anything about you, and that’s as it should be.

It’s not a memoir. It’s their story, if I’ve done my job right. We call it immersion reporting. How do you hang around long enough so that people forget you’re there?

Griswold: You and I are those old-school types, that’s what we believe. It’s not a memoir. It’s their story, if I’ve done my job right. We call it immersion reporting. How do you hang around long enough so that people forget you’re there? That’s really what this book is about. I only use the first person, I only use the “I,” when it would be disingenuous to not be there, when it’s clear that if I wasn’t there it wouldn’t be happening.

Kotlowitz: You spent a lot of time with Stacey and these neighbors, and I know from my own personal experience that it’s a really hard process. People who have never told their stories before—certainly never told them in this public way—there’s this kind of implicit trust. How do you reckon with that? I know in the end your loyalty is to your reader, but I know you also dedicate the book to the kids.

Griswold: They absolutely became a part of my life. It’s incredibly complicated to spend a lot of time in people’s lives, over a number of years. Stacey and her kids were in the battle for their lives, and they wanted somebody to be writing about that, and here I was showing up, and they really didn’t know what I was doing. That was really challenging. When I finished the book, I went down—I’d never done this before—with some pretty clear ground rules of, “We can’t change anything that’s factually accurate.” But I went and sat at Stacey’s kitchen table, and I read her the entire book.

Kotlowitz: Wow.

Griswold: I thought: I don’t have the right to show up this intimately in somebody’s life over this much time if I’m not going to take the responsibility and sit face-to-face and share whatever it is.

Kotlowitz: And how was that experience?

Griswold: It was pretty profound. And the thing about Stacey that’s remarkable—I mean, she is a citizen hero in Trump’s America. Her whole family voted for Trump; these are her politics. And she took a responsibility in listening to it. She didn’t want to hear it. It wasn’t like she was like, “Great, there’s a book about me.” She didn’t want to relive this. But she feels it’s her responsibility to other people with children to be witnessed, to share what she’s been through.

Kotlowitz: And one of the beauties of this book is both the intimacy and the empathy that comes across. I actually wanted to read just a little. I fell in love with Stacey. She’s just this really—scrappy doesn’t even do her justice—and there’s this moment when she’s forced to abandon her farmhouse, and so she leaves. And one of the things that happens in this community when you leave your land is the scavengers come and take all of the copper out of your home. So, she left a note for the scavengers outside her farmhouse that I love.

“To the ignorant motherfuckers who keep breaking into my house: it’s bad enough that my children and I have been homeless for two and a half years but now I have to deal with this. Your greediness has cost me over $35,000 in damages and the bank has put a forced insurance of $5,000 on my mortgage, so as of January 1st, my mortgage payment goes up $500 a month. I hope you feel good about what you have done and I hope you know that the contamination in this house causes cancer, so keep coming back you losers. I hope you rot with cancer!!! And when you’re spending all your scrap money I hope you think about what you are taking away from my children.”

Eliza Griswold, a Guggenheim fellow, is the author of a collection of poems, Wideawake Field (FSG, 2007), and a nonfiction book, The Tenth Parallel: Dispatches from the Fault Line Between Christianity and Islam (FSG, 2010), a New York Times bestseller that was awarded the J. Anthony Lukas Prize. She is the translator of I Am the Beggar of the World: Landays from Contemporary Afghanistan (FSG, 2015).

Alex Kotlowitz is the author of three books, including the national bestseller There Are No Children Here, which the New York Public Library selected as one of the 150 most important books of the twentieth century. A former staff writer at The Wall Street Journal, Alex has long been a regular contributor to The New York Times Magazine and public radio’s This American Life. His stories have also appeared in The New Yorker, Granta, Rolling Stone, The Chicago Tribune, Slate and The Washington Post, as well as on PBS (Frontline, the MacNeil-Lehrer NewsHour, and Media Matters) and on NPR’s All Things Considered and Morning Edition. He lives just outside Chicago with his wife, Maria Woltjen, who directs the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights, and their two children, Mattie and Lucas.