As anyone who writes historical fiction knows, research becomes your partner. If you do too much, it becomes your master, weighing down the narrative; too little, the reader fails to be transported to the world of the book. The primary challenge I give myself is to make the place and time come alive for my reader. Once the world of the novel is created, the reader can make that leap of empathy for characters that are not only possibly separated from her by class, race, or gender, but, uniquely in the case of historical novels, time.

My latest novel, The Removes, is set in the American West during the mid-1800s, seen through the eyes of General Custer; his wife Libbie; and Anne Cummins, a captive taken by the Cheyenne. One of my goals in the book was to avoid the mythologies that have grown around this period and the genre of the Western in general.

What I found most difficult was trying to find detailed information on Native American culture, specifically the Plains Indians. Sometimes authors receive research “gifts.” One of the most inspiring of these gifts that I came across when writing The Removes was the captivity narrative, a genre that was popular in the day. The captivity narrative is an immersion, albeit forced, into the Native American culture. My main character, Anne, is fifteen when she is abducted. For six years she lives a life forced on her, but during this time her views gradually change as the unknown “other” dissolves into individual personas—some good, some bad—and they become human. But I still longed to have my understanding of Plains Indian culture not filtered by a genre that in many instances was written specifically to justify our government’s treatment of indigenous peoples. That was when I received my second research gift through Native American ledger art.

I came across the Red Horse pictographs in an exhibition at Stanford University as I was deciding at what historical moment to end the book. I resisted writing about the Battle of Little Bighorn for several reasons. The primary one is that I didn’t want a giant set piece that has been so extensively written about to overshadow my main interest: What led Custer to that exact moment in history? The total annihilation of all five companies of the 7th Cavalry under Custer’s command was a severe shock to the army and the nation, but it was not a shock to the victors. They had predicted victory and by sheer numbers they had the advantage. Other less known battles that I focused on instead—the Battle of Washita and the Battle of Sand Creek, which are more correctly labeled massacres—had all the elements that forecast an outcome like Little Bighorn. Still, skirting Custer’s Last Stand seemed a bit disingenuous. But, seeing the battle through the eyes of the victors felt right.

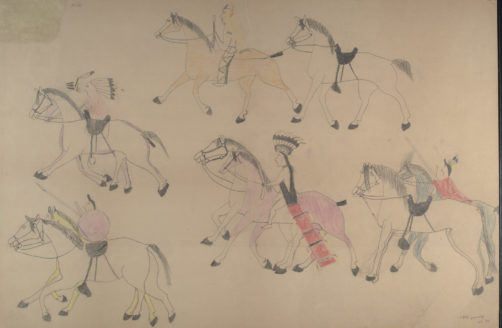

Ledger drawings are pictographic images of historical events found throughout Native American art. These compositions are made using ledger books furnished by European colonists and military personnel. Seeing images by someone who witnessed the Little Bighorn battle was startling. It made it real. I had the visceral, goosebump moment when I felt what the participants might have felt. This was a glimpse through the eyes of the culture that didn’t write the histories in the books, that didn’t have the last word.

This was a glimpse through the eyes of the culture that didn’t write the histories in the books, that didn’t have the last word.

Red Horse, a Minneconjou Lakota Sioux, was both a respected warrior and artist. Five years after the Little Bighorn battle, as his testimony, he made over forty drawings. What is striking about them is that taken as a whole they function much as a film does: We are inundated by a series of striking images, details we would not otherwise know. We see the village of teepees. Individual Lakota warriors are identified by dress and decorated horse—these were men the artist knew alongside whom he fought. In contrast, lines of soldiers appear largely indistinguishable from one another which is how they would have appeared to the natives being attacked—a killing machine. Strikingly, in all the images there is no soldier identifiable as Custer.

Compare this to the falsely heroic depiction of the battle, “Custer’s Last Stand,” by Cassilly Adams, that is entirely imagined yet became the image most widely received by white audiences. It was even distributed as a lithograph by Anheuser-Busch and could be found in bars across the country. The chasm between these two divergent versions of reality is unbridgeable.

In the Red Horse version, as the two sides engage in battle, there is brutality and carnage. Blood spouts from each side. The death of soldiers and warriors is shown with graphic starkness. A field of dead horses appears almost otherworldly. Knowing the value which both Native American culture and the American cavalry placed on horses, it is one of the chilling costs of war that we might otherwise overlook. Details such as the pages of hoof prints indicating the numbers and movement of mounted warriors and soldiers, and the emptiness after their passing. Taken as a whole, the collection is a moving portrayal of the waste of war.

Taken as a whole, the collection is a moving portrayal of the waste of war.

Some scholars point to the pictographs as proof Custer did not have a heroic last stand, but that reduces the message of the drawings to eyewitness reportage. Custer’s miscalculation, and his hubris, are well known; his loss of his entire command is common knowledge. However, in Lakota recollections of the battle, there is acknowledgement of his bravery as a leader of men. His military boldness was both his success and his doom. The truth of history is always more nuanced than the generalizations of history that eventually become talking points. The Red Horse pictographs enriched my understanding of the battle by allowing me to imagine my way to writing about a distant time and culture that is the beating heart of our nation’s history.

Tatjana Soli is the bestselling author of The Lotus Eaters, The Forgetting Tree, and The Last Good Paradise. Her work has been awarded the UK’s James Tait Black Prize and been a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Award. Her books have also been twice listed as a New York Times Notable Book. She lives on the Monterey Peninsula of California.