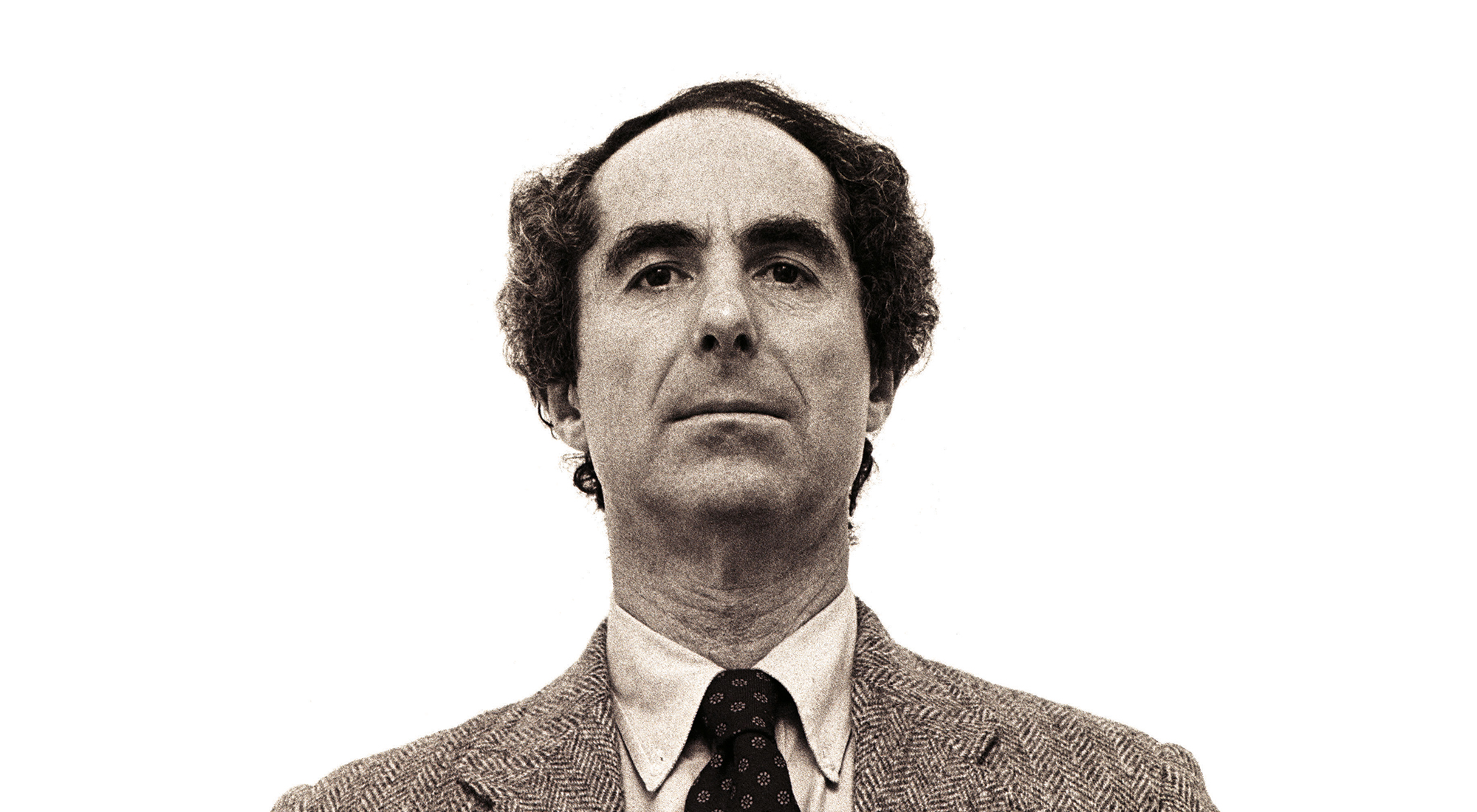

Philip Roth, one of the most renowned writers of our time, passed away last week at the age of 85 in Manhattan. We are extremely honored to have published some of his work. The following is an excerpt from Roth Unbound, Claudia Roth Pierpont’s in-depth look at his life through his art.

“What the stories all have in common,” Roth sums up, “is the cataclysm. Here are four men of different ages, brought down.” Roth had weathered his own share. His beloved dead now included his brother: Sandy Roth died in May 2009, at eighty-one, while Roth was working on Nemesis. So many of his Connecticut friends were dead that winters in his house had become almost unendurably lonely. And then there were all those drafts of Nemesis: written, he said, because he was having so much trouble getting it right but also, it seems, because he couldn’t bear to let it go. He didn’t have another book in sight, a situation that he described, in the fall of 2009, as “painful,” and he seemed to mean it viscerally. He was seventy-six, and it was just beginning to become clear that this would be the last novel he wrote. And then what?

The assailable man. The vulnerable man. The man who gets old, gets sick, can’t perform anymore: the man brought down. We have been discussing this subject in his work, in a suitably encroaching twilight, with suitable seriousness, when the esteemed author suddenly rises and begins to act out the stunned and bloodied Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull. LaMotta has just been beaten to a pulp in the ring by Sugar Ray Robinson. He’s lost the championship. He’s dripping blood. But he’s still on his feet and he’s now staggering toward me, proudly wheezing out the words—Roth does an excellent De Niro—“You never got me down, Ray. You hear me? You see? You never got me down, Ray, you never got me down.”

• • •

Roth also does a dead-on Marlon Brando as Mark Antony, reciting “Friends, Romans, countrymen,” and getting remarkably far into the speech on the spur of the moment, as we walk through midtown on a sunny afternoon. He’s orating to the Roman populace, and it’s amazing how few people turn their heads. Later, he tells me that he watches The Godfather once a year and that he does it mostly for “the Daumier faces.”

• • •

It’s easy to see all the mistakes in his past work, he says—much harder with the newer things.

It’s easy to see all the mistakes in his past work, he says—much harder with the newer things. And the really early books make him squirm: the last, Israeli chapter of Portnoy’s Complaint, for example. And don’t even get him started on Goodbye, Columbus. “To begin with,” he says, “Aunt Gladys would have been of my parents’ generation, not an immigrant, so she wouldn’t have talked that way—that’s just wrong.” Aunt Gladys was right about the absence of Jews in Short Hills, though. (“So when do Jewish people live in Short Hills? They couldn’t be real Jews believe me.”) Jews had moved from Newark to Maplewood and South Orange after the war, he tells me—“those were the suburban paradises”—but Short Hills was still off-limits. This was not a mistake but a way of covering for the real family he knew. The only character he’s willing to stand up for is the girl, Brenda Patimkin. “She’s young, she’s decisive, she’s playful, she’s audacious,” he says, just like the girl who inspired her. It’s the voice of the hero, Neil Klugman, that he now finds “a bit smug.” Where did that smugness come from? “Well, there was a lot of superiority going around about the suburbs. But I can’t blame anybody else. That was just me.”

• • •

He sometimes quotes the last lines of The Great Gatsby, but admits that he has some reservations about the book: “It’s a bit melodious for my taste.” He believes that Hemingway was the stronger writer. I mention Fitzgerald’s early draft of Gatsby, published about a dozen years ago, as Trimalchio, in which Gatsby’s attitude toward Daisy is harsher than in the finished book, and Gatsby himself is less of a glowing Don Quixote. He replies, “It sounds like it was probably better that way.”

• • •

None of the other distinguished honorees can have felt more honored than Roth, the FDR baby and lifelong Democrat, to be awarded the National Humanities Medal, by President Obama, in March 2011. He is still excited when he shows me a video of the ceremony, beginning with the recipients of both the Arts and Humanities medals waiting in the White House Green Room—Joyce Carol Oates and Sonny Rollins among them—when suddenly the door opens and the president walks in. This was a break in protocol, Obama explains a little later, at the ceremony; he was meant to make a formal entrance into the East Room after the medal recipients were seated in the hall. But he says that he couldn’t wait to see these people. And Roth is the first person the president sees: he lights up in recognition and breaks into a big smile as he calls out, “Philip Roth!” Roth replies exactly in kind, with the same tone of surprise and delight (what a surprise to see you here!): “President Obama!”

The ceremony is dignified, inspiring. The president, at the lectern, speaks feelingly of “thumb-worn editions of these works of art and these old records,” works that “helped inspire me or get me through a tough day or take risks that I might not otherwise have taken.” American art, he proclaims, is one of the country’s major “tools of change and of progress, of revolution and ferment.” He speaks jointly of the works of Harper Lee—an honoree who was not present—and Roth, an unlikely pair who have “chronicled the American experience from the streets of Newark to the courts of Alabama.” After a tribute to Lee’s teachings about racism, the president says, quietly sly, “How many young people have learned to think by reading the exploits of Portnoy and his complaints?” There is a double wave of laughter: at first, people are laughing to themselves, and then—after Obama has taken a long, deadpan pause—there is a second, bigger swell when they realize that everyone else is laughing, too.

Finally, it is time to present the awards. A military officer recites a very brief summary of each recipient’s achievements. Two of Roth’s books are cited: Portnoy’s Complaint, of course, and American Pastoral—“which won the 1998 Pulitzer Prize.” (The young officer mispronounces the word “pastoral,” but then no one has told him how to pronounce the name W.E.B. Du Bois in the citation for the biographer Arnold Rampersad.) Up on the stage, Roth stares out at the crowd, as though trying to fix the moment in his mind. The president says a few confidential words as he lowers the medallion, on its red ribbon, over Roth’s bowed head. Roth tells me that Obama said, “You’re not slowing down at all.” And that he had replied, “Oh yes, Mr. President, I am.”

• • •

He’s had a lot of back pain in recent years and is facing major surgery. It’s the spring of 2012, and I speculate that, when he has recovered and is pain-free and back in Connecticut, he may yet write another novel. He sighs and says, “I hope not.”

• • •

We are talking about his first wife, Maggie, and I ask if he really believes, as Nathan Zuckerman claims in The Facts, that she was responsible for releasing him from the role of a pleasing, analytic good boy who would never have been much of a writer—that, in a literary sense, he owes her big. At first he seems taken aback, and then he growls, “Nathan Zuckerman was making it up. I don’t owe her shit.”

He expands on the subject. “She interrupted my life and took a part of it away,” he says, quietly now. “She also changed it forever.” He is currently recovering from back surgery, and when the subject comes up again a few months later, and he is feeling healthier and stronger, he says that Zuckerman was right. But today he is thinking about more than the work.

He has just seen Ann Mudge, his girlfriend of the mid-sixties, and is under the spell of counterlives past. He hadn’t seen her in more than forty years. “The only person who could write this, it isn’t me, it’s Proust,” he says. She is six months older than him—that makes her eighty, as we speak—and has been long and happily married. “She was a little old white-haired lady I wouldn’t recognize in the street,” he says, “until she sat down and began to speak, and then I began to see her face. And you know what never changes? The facial expressions—they’re exactly the same.”

They broke up in 1968, before the publication of Portnoy—just months after Maggie’s death. Because “I had just flown the coop,” he says, and had to be free.

They had talked for hours, remembering. “Thank God I’m not writing anymore, because I’d be driving myself crazy, trying to get it down.

“Maggie took up the years from twenty-three to thirty-five. If I hadn’t married Maggie, I would have married someone else—probably Ann. We would have had a kid, I would have fooled around, we would have got divorced, if I’d followed the normal pattern. Who knows? But life would have been different.”

This day, at least, he concludes, “I wish it had never happened. Even if she gave me everything.”

• • •

At first, he didn’t know what to do. With Nemesis completed, he found himself, for the first time in more than half a century, unchained (as Zuckerman says of Lonoff) from his talent. He made lists of possible subjects for books, but none of them seemed compelling. He was afraid he would become depressed, would suffer from the lack of occupation, would be unable to cope with life without the daily application of his energies to the written page. But none of these things happened. He was utterly surprised to find that he felt free.

• • •

He is besotted with the eight-year-old twins of a former girlfriend, especially the girl. The boy is wonderful, he likes trucks and baseball, but Roth and the girl are writing books together. This was her idea. She is extraordinarily smart and verbally advanced, he says, “although I don’t want to sound like a grandfather.” Each of the authors writes a sentence a day, taking turns. The first thing he does in the morning is check his e-mail to see what she has sent him. They have already completed a couple of books. He whoops with delight at her reply to his suggestion that they have gone far enough with a particular story: “No, it’s not enough!” Such brashness, such eagerness, such playfulness! He can’t stop marveling, and wonders if “growing up with feminism so fully established” might account for the confidence of this “dazzling child”?

• • •

The joys of a non-writing life: phone calls and letters to friends, exercise, reading political histories and biographies. Tony Judt’s Postwar, Simon Sebag Montefiore’s book on Stalin, books on Stalin and Hitler by Alan Bullock and John Lukacs, the three volumes of Arthur Schlesinger’s study of FDR, several books about Eleanor Roosevelt, Sean Wilentz’s The Age of Reagan, Robert Caro’s latest volume on Lyndon Johnson, David Nasaw’s biography of Joseph Kennedy. There was a mild furor in the literary press when he was quoted as saying that he doesn’t read fiction anymore, and it’s true that a lot of his time is taken up with books like these.

But he is also reading fiction—or, rather, rereading the books that mattered so much to him when he was young: “Because I asked myself, ‘Am I never going to read Conrad again?’”

There is also Turgenev, including the letters and biographies; there is Faulkner, confirming for him that As I Lay Dying is “the best book of the first half of the twentieth century in America” and that, reading the first fifty pages of Absalom, Absalom!, “you might as well be a kitten caught in the yarn.” Hemingway, of course: In Our Time (“Talk about magic, that’s magic”). And A Farewell to Arms: “a nearly perfect book—no, a perfect book. The blending of the war and the love affair is extraordinary, and it has all this aggressive male banter, like a faint echo of the war. But it’s the love affair I’m a sucker for, the way they joust at each other in the beginning, until she says, ‘Do we have to go on and talk this way?’ ” And the later Hemingway, so underrated. Islands in the Stream: “He’d never written about having children like this before.” And even The Garden of Eden, which was cobbled together posthumously from his papers and shows him “coming clean about sex, which I don’t think he ever did before.”

Greatest lines in literature: In Crime and Punishment, Dunya, Raskolnikov’s sister, goes to see Svidrigailov in his apartment. Svidrigailov is an appalling character, a villain—“with,” Roth says, “a sinister, devillike charm.” He’s cornering Dunya, “literally manipulating her into a corner of the room,” threatening rape. (Roth has written about this line in Operation Shylock, but all he’s thinking about now is how much he likes it.) “And he’s just about to make a move when she pulls a pistol out of her purse—and it’s then that he has the greatest line in literature,” Roth declares: “‘That changes everything.’” He repeats the line with gusto—“‘That changes everything!’

“The other really great line,” he says, clearly enjoying himself, is in Ulysses, when Bloom sees Gerty MacDowell on the beach. “He doesn’t yet realize that she’s a cripple. He’s standing there watching her from maybe thirty yards away. He’s got his hand in his pocket, and I think he’s cut the pocket out of his pocket—didn’t he? If he didn’t, I’m going to use that sometime. But the next line is”— dramatic pause—“‘At it again.’

“‘At it again’! That combination of resignation, delight, and tolerance! That’s what I want it to say on my tombstone,” he concludes. “At it again.”

“‘At it again’! That combination of resignation, delight, and tolerance! That’s what I want it to say on my tombstone,” he concludes. “At it again.”

• • •

He has received a few old family photographs from a cousin on his mother’s side—among them one of his mother in her wedding dress. It’s a beautiful photograph, showing Bess Finkel on the day that she became Bess Roth—February 22, 1927—wearing an elegant gown with a long gossamer veil that trails over a rather grand staircase edged with greenery. He remembers, vaguely, the photo displayed among many others on the sideboard, near the dining table, during his childhood, but he hasn’t seen it in more than half a century. The real discovery, however, comes when he says to his cousin that he assumes the photo was taken in a rented hall—where, he also assumes, the marriage took place—and she replies that, no, this is the Finkel family home.

His mother was quite well-off as a child. It is a shock. She grew up in a big house on North Broad Street in Elizabeth. (The houses are mostly gone now.) And suddenly he begins to solve a family mystery that he never even realized was a mystery: why his father’s side of the family so dominated his childhood and why he saw so little of the relatives on his mother’s side. He saw plenty of his mother’s three sisters and of her brother, Mickey. But his mother’s father had three brothers, who lived with their wives and children not very far away; and these people he never saw at all.

The Finkels were prosperous. The four brothers ran a fuel business in Elizabeth—coal and, later, oil—and he can now remember seeing the big trucks with Finkel Fuels across the sides. As he pieces it together, his grandfather Finkel—Philip, for whom he was named—had a falling- out with his brothers in 1928, took his share of the business in cash, and lost it all in the Crash. The big house was sold in 1929. His grandfather’s death a couple of years later left his widowed grandmother in tough circumstances; apparently, the brothers refused to come to her aid. Hard feelings; broken relations; family schism. But Bess Finkel had grown up, before any of this happened, in circumstances that he had never remotely imagined. He knew that she had finished high school, unlike his father, and that she had trained to be a legal secretary. But he had never realized quite how far down she stepped to marry Herman Roth.

The feuds, the coal business, the money, the house, the loss of the money—“It doesn’t matter to me personally,” he says. “I had plenty of family. But think of what I missed out in the writing!”

• • •

He is recalling the little Irish girl he loved when he was twelve. One Sunday, he was visiting a cousin, also named Philip—his Aunt Ethel’s son, born a year before him and named after the same grandfather—up in Pelham, with his family. It was summertime, and he was having such a good time playing baseball with all the new kids—he remembers impressing them with his long ball—that his parents let him stay on for a few days. He used to sing “Peg o’ My Heart” to the little girl. (“It’s your Irish heart I’m after,” he croons, rather nicely, now.) “I had a terrific crush on her,” he recalls. And then he adds, thoughtfully, “I could get them.”

I laugh because this seems so obvious.

“Could you get them?” he asks. Well, yes, of course. (Doesn’t everyone?)

“That’s why we went into literature,” he concludes.

• • •

A few years back, a developer was threatening to build forty- four houses on land across the road from Roth’s Connecticut house, and, as he says, he “dug into my pocket” and bought the land himself. He now owns almost two hundred and fifty acres, and he seems to know every tree on them. He has become a connoisseur of bark and lichen. On the day that I arrived for a visit, in the summer of 2012, Roth’s close friend and neighbor Mia Farrow was there with him to greet me, and we took a walk along a wide path mown through open fields. As Roth (literally) showed me the lay of the land, it felt as though Daisy Buchanan were floating along beside us.

And that was not the only literary shiver. Over there—Roth’s writing studio—is Zuckerman’s lonely two-room cabin, and here are Lonoff’s giant maple trees. Lonoff’s apple orchard is down to just a few living trees, but the fruit is sweet. And the candlelit dinner, on this late summer night, in the presence of the actress and the writer and with crickets chirping in the background, is as Chekhovian as anything in The Professor of Desire.

Conversation over dinner turns to the Obama-Romney battle and, in particular, to concerns over campaign financing. I mention that one of Romney’s backers, Sheldon Adelson, owns the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas, and Farrow replies, laughing, “I once got married at the Sands!” Roth is wholly delighted—“You mean to Frank Sinatra?!”

She has a wedding picture on her cell phone.

• • •

Old habits die hard. He is no longer writing all the time but, somehow, pages are piling up. Not fiction, though. He says that he hasn’t the strength anymore “to keep pulling something out of nothing.” Instead, there are notes, thoughts, corrections: so many things have been written about him, so many of them wrong, and they are already hardening into history. These are writings for the record, for the future. A letter to Wikipedia, attempting to correct its claims about his inspiration for The Human Stain, and subsequently published on The New Yorker website, has generated an astonishing amount of outrage. He’s seen enough outrage. Better to keep his head down. He’s written a wonderful account of the American writers who shaped his youth—it’s about them, not about him—but he’s done it just for the pleasure of doing it. He can’t stop writing, can’t stop turning life into words.

He can’t stop writing, can’t stop turning life into words.

• • •

Both Roth’s agent and The New York Times tried to be discreet about the reason for a recent interview, but Roth was quick to sniff it out: the Times is updating his obituary. He is not in the least put out by the idea; it’s hardly as though he hadn’t thought about what’s coming next. But there is one thing that disturbs him. The Times will, of course, use Times reviews in summing up his career. “Even in death,” he says, “you get a bad review!”

• • •

We are standing outside Carnegie Hall, during intermission, on a beautiful spring evening. The Emerson String Quartet has just performed, first excerpts from Bach’s The Art of Fugue and then Shostakovich’s String Quartet no. 15. Roth, who rarely misses an Emerson concert, has invited several friends to join him, and other friends who happen to be in the audience have been coming by to say hello. These include an elegant older woman with red hair, still extremely attractive, who goes far back in his life—her name is Maxine Groffsky and she was the inspiration for Brenda Patimkin. (Roth recalls that the hair was once incredibly beautiful, “the color of an Irish setter,” and he thinks that she may have been flirting with him tonight: “Maybe we’ll have an affair every fifty-one years.”) Bowled over by the gorgeously death-haunted Shostakovich, he admits that he has never really liked The Art of Fugue. “Too obsessive-compulsive,” he says. And then, directly to Bach: “You’ve figured it out already! You can stop!” To us, he elaborates on his agitation: “He’s like a guy constantly checking his pockets, or worrying that he left the pilot light on!” Who had any idea that Bach could be so funny?

The second half of the program is Beethoven’s String Quartet in B-flat Major, op. 130, played with its original ending, the Grosse Fuge, the most formidable fugue in Western music: wild, dense, dissonant, intensely dramatic, even argumentative, running the emotional gamut. The performance is electric, and coming out of the theater, Roth says that now he understands why we listened to the Bach: “the Beethoven is like Bach on drugs!” We are all more than a little punchy as we head off into the city streets, and soon we are laughing so hard that we can hardly walk, as Roth—master of literary countervoices, I can’t help but think—continues to expand on the fugue: “How crazy all those voices are! Like four lunatics in an asylum! Four madmen screaming away all on their own and then…they turn out to be together!” He tells one of our company, a psychiatrist, that under non-musical circumstances she would have to give each of them a shot. “Four guys who all think they are God!”

People peel off in various directions, and then, standing on Eighth Avenue, he is hailing a taxi, arm raised high. It’s a bit of a wait, and now strangers passing by are saying hello. A gray-haired man crossing the avenue launches in. “Hi, I’ve loved everything you’ve done for the last fifty years,” he says, and quickly adds, “I’m older than I look.” Roth, who has been quietly humming to himself, emerges from his thoughts in time to respond, “I’m older than I look, too.” Another man crossing the street simply reaches up to Roth’s outraised hand, grabs it, and says, “Bravo, Maestro!” (This is still the Carnegie crowd, musically minded.) This happens too quickly for Roth to respond, or to fully relinquish the music going through his head. He doesn’t seem pleased or displeased; he hardly seems to have noticed. And now I can distinctly make out the melody issuing from him, the crazy, crossing voices, as he stands in the New York night, traffic flashing by, humming the Grosse Fuge.

Philip Roth (1933-2018) was the award-winning author of Goodbye, Columbus, Portnoy’s Complaint, The Great American Novel, and the books that became known as the Zuckerman Trilogy (The Ghost Writer, Zuckerman Unbound, The Anatomy Lesson), among many others. His honors include two National Book Awards, two National Book Critics Circle Awards, three PEN/Faulkner Awards, the Man Booker International Prize, the National Humanities Medal, and the Pulitzer Prize.

Born in Newark, New Jersey, Philip studied literature at Bucknell University, graduating magna cum laude with a B.A., and at the University of Chicago where he received an M.A. From 1955 to 1991, he taught writing and literature classes on the faculties of the University of Chicago, Princeton University, and the University of Pennsylvania.

In 2005, he was only the third living writer whose books were published by the Library of America. He lived in Manhattan and Connecticut.

Claudia Roth Pierpont is a staff writer for The New Yorker, where she has written about the arts for more than twenty years. The subjects of her articles have ranged from James Baldwin to Katharine Hepburn, from Machiavelli to Mae West. A collection of Pierpont’s essays on women writers, Passionate Minds: Women Rewriting the World, was published in 2000 and was nominated for a National Book Critics Circle Award. Pierpont has been the recipient of a Whiting Writers’ Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a fellowship at the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers of the New York Public Library. She has a PhD in Italian Renaissance art history from New York University. She lives in New York City.