New York Times bestselling author David Duchovny reimagines the Irish mythological figure of Emer with Miss Subways, a darkly comic fantasy love story set in New York City. Emer is just a woman living in the city, taking the subway, dreaming of being a writer. But is this the only path she’s on? Duchovny’s writing takes us on a journey down parallel tracks of time and love, introducing us to various supernatural forces along the way. A tale of love lost and regained, Miss Subways is also a love letter to the city where Duchovny grew up. What follows is a conversation between Duchovny and Sam Roberts from the book’s launch event at Barnes & Noble.

Sam Roberts: David, you dedicate this book to your mother. You point out that you took one of your first subway rides with her, though you hardly ever got to where you were going. You point out that the destination wasn’t as important as the ride. What did you mean by that?

David Duchovny: I was just trying to be nice. I would have actually liked to have gotten where I had meant to go. My mother is from Scotland and is not conversant with the subway so well, and we were trying to get to the Museum of Natural History, which is where a lot of little boys like to go. I was obsessed with dinosaurs when I was a young kid. We got on one train and then got on other trains that hooked up with many other trains—and all of a sudden we were above ground, which was strange because to us the definition of a subway was that it’s underground. And the doors opened and we were in Jamaica, Queens—I saw the word Jamaica on a sign and I was like, “Oh shit.” Not even the right borough. I was just looking for the beach.

It doesn’t matter if you get to the right place—you’re going to get to some place.

What I was saying in the dedication was along the same lines as William Blake, who says, “If the fool would persist in his folly he would become wise.” The idea of just getting off your ass and trying to take the journey. It doesn’t matter if you get to the right place—you’re going to get to some place. And usually the mistakes you make along the way are going to be the most significant for you.

Roberts: One of the things you said in your interview with Maureen Dowd for The New York Times is that you don’t want people to like this book and say, “It’s pretty good for an actor.”

Duchovny: No, I do. I like that. [laughter]

Roberts: But you do have great credentials as a writer as well. You’ve written two books and they’ve gotten good reviews. You went to Princeton. You went to Yale, majored in English literature. You wrote—or started—a doctoral thesis about something I can barely pronounce. I don’t think agents are salivating over it to make a movie. I may be wrong.

Duchovny: It’s only been forty years. It still might happen.

Roberts: But this book, Miss Subways, was inspired by a play you saw at Yale as a graduate student ages ago. A sort of Celtic fantasy. How did it get transformed decades later into a book about Miss Subways? The competition that used to be those placards on the subway system.

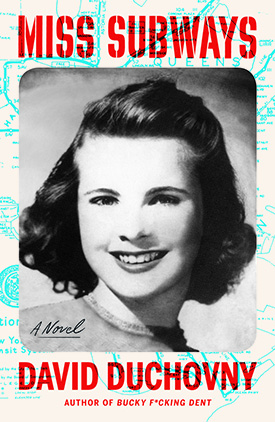

Duchovny: I believe the woman on the book jacket is actually the first Miss Subways. I didn’t put her on the cover because she was the first. I saw her when I was researching and she just jumped out as being innocent yet mysterious.

In the play, the Irish King, Cuchulain, has killed his son in battle by mistake because he’s such a crazy warrior, he kills everything around him, and ends up killing his son. Now he’s out in the ocean fighting the waves because he’s mortified that he killed his own son. He’s going to drown fighting the deathless sea, as Yeats calls it. The demon comes to Cuchulain’s wife, Emer, and says he’s going to die but she can save him if she renounces her fantasy of having an old age with him. He’s out running with these concubines, he’s a youngish man, and she has a hope that in his old age he’ll come back to her. And so she has to renounce this fantasy or this hope to save him. And she does it. And that just stayed with me forever. I saw it in 1985 and I thought it was very—if not romantic, then at least moving in some way. Just always stayed with me.

I wanted to modernize it for my book and eventually I was able to. The subway came into mind just mythologically as being underground and I was writing about a woman whose power was underground and it just all kind of made sense. And then those trains of thought that I was subjected to when I would ride the subway—which were quotes from literature and philosophy—I just thought it was kind of an oracle and an easy way into some of the philosophical ideas that I was dealing with in the book.

Roberts: In the acknowledgments you thank your teachers at Collegiate School for teaching you how to write. Can you be taught how to write?

Duchovny: I think so. Collegiate really was a writing school. Writing was the foundation of all the liberal arts subjects in the school. You had to learn how to write. I remember when I was at Yale, I had this professor named Michael Cook who would talk about how he couldn’t even think without a pencil in his hand—that writing was thinking. It’s strange to me now that I actually write—I can’t type fast, I failed that course. So I write without a computer; I’ve always written with a pen or a pencil.

Roberts: Do you prefer writing, acting, singing—which? You’re sort of a Renaissance man in that sense.

Duchovny: I like them all. Different things occur to me to express in different ways. Acting is my business. I’ve been doing that for a long time. I enjoy doing that now because I feel like I’ve served an apprenticeship for thirty years and I know what I’m doing. So I’m not tired of it. I’m actually interested in it maybe more than ever. Writing to me is something I’ve always done in private anyway. And music is fairly new. They all have different kinds of attractions for me.

Roberts: I interviewed Danny Aiello one time and he said that acting was an escape for him because he always was able to escape into other characters. I have to say I find writing—and particularly journalism—as something of an escape because I am always kind of an outsider looking at other people, other events. Do you find that for yourself too in either of those two things? And if so what are you escaping from?

Duchovny: I think any time that I can focus—any time that I can intensely focus for any length of time—whether it’s an hour or five hours writing or if it’s the duration of a part I’m acting or writing music or performing music then to me that’s the escape. Any time you can kind of focus yourself on an outside object or project. Then that’s the vacation. I don’t really have hobbies because with these activities I escape from my mind, even if I’m using my mind, and I find it very invigorating to be able to do these things. I don’t get tired of doing them.

Roberts: Do you write differently as an actor? When the Times reviewed Bucky F*cking Dent, Joe Salvatore wrote, “A fiction feature once told us that we should know every detail about the characters we create down to the type of bath towel they prefer. Even if the towel never appears in the story.” That advice smacked of Stanislavski’s method and the reviewer said, “I wondered a bit enviously if actors who tried their hand at writing fiction would invent characters with greater depth than mere scribblers.” Do they? Do you bring another level of depth to writing?

I think in terms of dialogue.

Duchovny: No, I don’t think so. I think in terms of dialogue. I enjoy writing dialogue in my books a lot because I think I know what good dialogue sounds like and that comes from years of speaking both good and bad dialogue. You get to luxuriate in the process of the book with the dialogue, and if I had to make this into a movie I’d have to cut a lot of dialogue. I let the characters speak more in a book than in a screenplay and that’s fun for me.

Roberts: You said the hardest thing about writing a novel in the age of Trump is that we’re all characters in a Beckett play directed by Sartre.

Duchovny: Well, I said that it’s just the fact of Trump that makes it hard because everyone is talking about Trump all the time and supposedly to be an adult is to speak of politics now which to me is an oxymoron. That’s all anybody talks about is politics. They talk about Trump so it has kind of dwarfed every other kind of enterprise an artist can do and everything is seen through that lens. That’s crap. This will pass. This will all pass. Then we’ll see what’s left standing.

Roberts: When you wrote Miss Subways what did you want people to walk away with when they finished?

Duchovny: I’m just trying to tell an engaging story. I wanted to tell a story about a woman who goes from being the second lead in her life story to being the lead in her life story. Who goes from being somebody who helps a man write a work of nonfiction to somebody who writes her own work of fiction. And I wanted to make the case that all three of those versions that you get in this book are possibilities and might even be happening all at the same time on some psychic level and that we do have the power to choose, because choice is the wager that the demon brings to the woman. It’s really about making choices and who controls the narrative of your life.

Roberts: You have a great ear for dialogue. Why do you think you’re so able to write from different points of view—including a woman’s point of view?

Duchovny: I think it’s about empathy, and I think as an artist, what you’re trying to do is put your mind or your heart or soul into something else and figure out what makes that tick, whether that’s a man or a woman or a race or religion or a dog or a cat or a refrigerator. You’ve got to get out of yourself and into that thing. And whether or not I do a good job of it is up to other people to decide. I think we live in a time when people are told that they’re only to write or act or do what they are or what they know—I think that’s dangerous. At the heart of any kind of artistic endeavor is actually empathy. And that’s always a good thing.

At the heart of any kind of artistic endeavor is actually empathy. And that’s always a good thing.

Roberts: When you were talking to the Times about being empathetic and speaking in the voice of a woman or speaking in the voice of anyone else that you’re not, you also said that after the Harvey Weinstein revelations you had to re-educate yourself like so many other people, like so many other men. How do you do that? And how far do you go?

Duchovny: Well I think you just say it doesn’t matter how I feel or how I’ve acted. Apparently there’s been a lot of other bad behavior that I either turned away from or didn’t know about, and I have to accept the fact that this is way more prevalent than it would be in my own mind. So if you’re not being part of the solution you’re being part of the problem. I think speaking up is important.

Roberts: Why do you write so many things—two of the three books at least—that involve the surreal?

Duchovny: I guess with the last two books what I’ve done is start with a historical event. In Bucky I started with the game where the Yankees beat the Sox and won the playoffs, and then I make up the rest or a lot of it from there. But I use it as an underpinning. And in this I guess I’m using the Miss Subways competition and New York itself as a realistic underpinning for the story I’m trying to tell or retell.

Roberts: What do you think the impact of the books is? I mean you quoted—I think in the Bucky Dent book—you quoted Coleridge, “Hast thou a charm to stay the morning-star.” The truest, saddest line in literature. Do words have an influence on the world? Have you written words that have an influence on the world? Or spoken words that have an influence on the world?

Duchovny: I remember writing a note to my son to get some milk and he did it.

Roberts: That’s about as far as it went.

Duchovny: That’s about the biggest claim I could make. I don’t know. Certain words are spoken by certain people in certain situations that can have a lot of power. Words in a book, perhaps. They’ve affected me. I’m quoting them. They had power over me. They continue to exercise power over me.

Roberts: In the dedication, one of the things you dedicate the book to is New York City. You say, “I will leave you one day but not yet.” Why will you leave and why not yet? What do you like most about the city?

Duchovny: I’ve got to leave sometime.

Roberts: Why?

Duchovny: I’ve been here a long time. I grew up here. I feel like I’ve got to get out. Honestly, the city I deal with is a city of the past. It’s the city I grew up with. While writing, I had to bring the city in my mind up to date. I got a lot of it wrong in the beginning because I was just going off of what I remembered. The city for people that grew up in it is filled with memories on every corner, even though the corners all look very different for the most part. I like that it has a lot of that for me, that it’s a city of memory for me. But in the present day, the food’s really good.

Roberts: And finally, you once said that Mulder is the worst FBI agent you could ever imagine. Why is that?

Duchovny: Well he never solved any cases. He dealt with things that didn’t have a lot of evidence. He was always Cassandra crying into the wilderness.

Roberts: But the truth was out there.

Duchovny: For a very a long time.

David Duchovny is a television, stage, and screen actor, as well as a screenwriter and director. He lives in New York and Los Angeles.

Sam Roberts is a writer for The New York Times. He was formerly city editor for The New York Daily News. His reporting has won prizes, including awards from the Newspaper Guild of New York and the Peter Kihss Award for the City of New York. His books include Who We Are Now and The Brother, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. His magazine articles have appeared in The New York Times Magazine, the New Republic, New York Magazine, and Empire State Report. He lives—where else?—in New York City.